When chemical engineer Don Pettit, age 69, blasts off for the International Space Station (ISS) this summer, he will become the second-oldest NASA astronaut in space, after the legendary John Glenn, who spent nine days onboard the space shuttle Discovery at the age of 77 in 1998. Pettit will spend a full six months in orbit during a time of high tension between the U.S. and Russia. Space exploration is one of the few areas in which the two countries still cooperate, and Pettit, a veteran of three prior missions, is now training for ISS Expedition 72 in an area sometimes referred to as Star City on the outskirts of Moscow.

While some astronauts spend their scarce off-duty hours on the ISS with activities such as reading books, chatting with family back on Earth or surfing the Internet, Pettit carves out time for what he calls “science of opportunity.” During a mission in 2003, for instance, his observations of how grains of sugar, salt and coffee aggregate in air-filled plastic bags allowed him and his fellow scientist and astronaut Stanley Love to serendipitously shed light on an enigmatic early step of planetary formation. Pettit plans to venture into new science-of-opportunity territory on his latest mission, too.

An inveterate tinkerer who spent 12 years at Los Alamos National Laboratory before joining the astronaut program, Pettit has devised, among other things, a cup that uses surface tension to allow astronauts to sip coffee in microgravity as if on Earth—for which he and Mark Weislogel of Portland State University were granted the first patent for an invention made in space. And he is an ardent science communicator, having created two video series, Saturday Morning Science and Science off the Sphere, that were filmed on the ISS.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Pettit and two Russian cosmonauts are slated to lift off on a Soyuz spacecraft from Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan on September 11.

[An edited transcript of the interview follows.]

You caught the space bug as a kid watching John Glenn on the Mercury flights in the early 1960s, and then you applied to the astronaut program right out of grad school. NASA turned you down the first three times. Why did you keep at it?

PETTIT: For the same reason you keep at any kind of activity or enterprise that takes a while to master: you can’t expect to do something the first time and be an expert at it. NASA invites about the top 120 in for interviews. And then, the fourth time, I got a phone call that asked if I was still interested in being an astronaut.

You were onboard the ISS when the space shuttle Columbia broke up during reentry into Earth’s atmosphere, killing all seven crew members. How did that affect you mentally?

Three of my classmates were on that mission, and the other four crewmates were really close to my wife and me. At first there was shock and disbelief. And we had to compartmentalize this loss and get back to work because we’re riding on a vehicle that needs constant attention, and you can’t go off on an emotional bender.

In normal times, what is the daily rhythm on the station?

We are scheduled for 12 hours a day. There’s usually another hour, sometimes two hours, of catch-up work because you can’t get everything done. So it’s not uncommon for astronauts to average about 13 hours a day, five and a half days a week. We’re lucky if we get one day a week off. You can’t work a gazillion hours every day for six months without having some off-duty time, and what crews choose to do is up to the individual. What recharges my batteries is to take advantage of the orbital environment and make observations that you cannot do on Earth.

One important insight you made during your off-duty hours was explaining an early step of planetary formation.

How millimeter-sized particles agglomerate into fist-sized objects in [microgravity]—yes.

And from there the sizes continue to grow—until we have full-fledged planets! Has your work on this stood the test of time?

Yeah, it has. Stan Love and I had a lot of fun with it. I’ve done work on this planetary formation concept now on my past three missions. And I’m planning to make some more observations on the upcoming mission.

What is your all-time favorite science-of-opportunity insight?

Oh, gosh! The suite of photography that I’ve been able to do—capturing moments on orbit with compositions and exposures that I really think tell a story.

For the upcoming mission, you’re bringing an improved version of your so-called barn-door tracker for space photography. Can you break down what that is and what it can do?

The original barn-door tracker [that I made] was made from a bunch of junk I found on the station, and its purpose was to counteract orbital motion and take longish exposures of Earth. It’s really a simple piece of equipment that amateur astronomers use: two pieces of wood with a piano hinge and a bolt between the two. You mount the hinge line so it points towards the North Star. Then you put a camera on one of the platforms. You know what the thread pitch is, so you can calculate that turning the bolt a quarter of a turn every five seconds will move the board at the sidereal rate of Earth’s motion. The pictures I took using this barn-door tracker were really the first time we got high-resolution images of cities at night.

What improvements have you made to the tracker?

What I’m flying next is a wind-up device based on a kitchen timer. It will reduce the motion so that the shaft turns one revolution every 90 minutes—that’s the station’s orbital period. And the station will pitch down at a rate that makes one revolution about its center of gravity. That way, the same side of the station points towards Earth as it goes around. This pitch rate is about four degrees a minute. I made a little wind-up timer that will move a camera mount at the pitch rate, so that way I can do time exposures primarily intended for pictures of the stars. Right now, because of the pitch rate, you really can’t make an exposure much longer than three seconds, or [else] the stars [will be] blurry. A three-second exposure just doesn’t bring out the dazzle of what you can see with your eye.

What can you see up there that astrophotography images fail to capture?

One thing is that when you look out the station window when your eyes are dark-adapted, there are colors of stars that you just can’t discern from Earth.

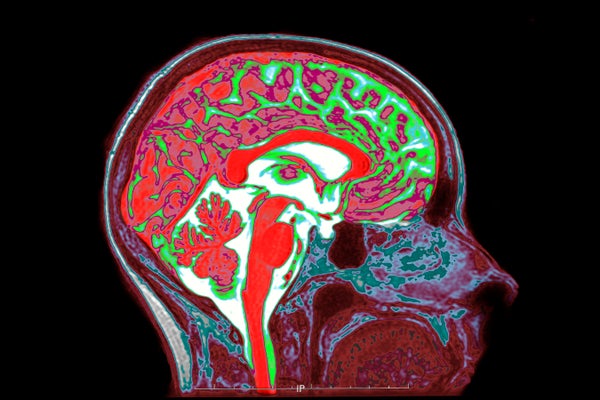

This is a composite of a series of images captured by NASA astronaut Don Pettit using a mounted camera on the Earth-orbiting International Space Station, approximately 240 miles above Earth.

Astronauts traveling to the ISS take along a preferred food package and a personal medical kit. How have you used this privilege to bring materials for personal science experiments?

We have these drink bags for coffee or whatever is your favorite beverage. I had the food people pack a couple of drink bags with unflavored gelatin. One of the things I would do is mix a little bit of instant mashed potato in with the gelatin solution and let it harden into a starchy, translucent sphere. From our first aid kit, I put a little drop of iodine on one side of this sphere, and you get to watch the diffusion of the iodine through the gelatin. It looked like it was developing Liesegang structures, where you have concentric logarithmic rings developed through a precipitation process.

Can you give a taste of other items you’re bringing on the upcoming mission?

So there’s sodium chloride on the station. It’s a saturated solution because a saltshaker wouldn’t work in space. With a colleague in Switzerland, [independent researcher] Pietro Fontana, we have published three peer-reviewed papers on the observations we’ve made from crystallizing the galley salt solution. The most recent paper was in [the Springer Nature journal] npj Microgravity. For the next mission, I’m bringing potassium chloride. We have a high-sodium diet on the space station. You could get upwards of 10 to 12 grams of salt a day. So I’m flying this salt substitute in my personal food, and I will also use it for crystallization experiments.

How does your scientific moonlighting mesh with the experiments NASA has you do as part of your job?

The programmatic experiments are all designed and conceived by people who have never been in space. They’re good experiments. But up there we come up with questions or observations that are completely different than what anybody on Earth could conceive of.

Has a science-of-opportunity insight led to a programmatic experiment?

Maybe two or three. The qualitative observations that Stan Love and I made showed there is something really interesting happening in particle aggregation in [microgravity]. A university team proposed and built hardware to continue, in a quantifiable way, this work.

Which Expedition 72 programmatic experiment excites you?

Some of my favorite involve human physiology in an environment we’re not intrinsically meant to be in. Using us as orbital guinea pigs is going to be one of the greatest legacies that come from the space station. Then there are physical science experiments, many dealing with combustion. When you have combustion in a weightless environment, you don’t get gravity-induced convection. For example, a normal candle will not burn because it won’t develop convection. It’ll consume the oxygen around it at a rate that’s faster than diffusion can provide new oxygen. The candle will burn for a handful of seconds and then snuff out.

What does that mean for fire risk on the station?

We know enough about combustion in a weightless environment to know what kind of materials you can use and what kind of materials you can’t use. For example, we used to have all kinds of Ziploc bags on the station. But some smart engineers on the ground figured out that polyethylene is way too flammable to leave out in the open cabin, and so they switched all our bags to Kynar.

Is a fire on the ISS your greatest fear?

That and [depressurization]. You get a little tiny leak, and maybe you have 24 hours to figure out how to plug it. Small leaks are not that big of a deal. The ugly scenario is having a module come unzipped. Think of a soda can that just goes bloop and explodes and just turns into a flat, crinkled piece of sheet metal. You’ve got a handful of seconds to figure out what to do.

Does that scenario ever creep into your thoughts on the ISS?

It’s always there in the back of your mind. We do a lot of training on the ground for both [depressurization] and fire. Tomorrow I’ll be in the simulator, and for that simulation we know ahead of time there’s gonna be a fire in the Russian segment of the space station. We’ll have to get in our Soyuz vehicle and do an emergency descent.

What’s the vibe like in Star City these days?

Some of the instructors here are the same I had the first time I came to Star City in 1999. We know each other’s spouses. We know each other’s children. Star City is a small community, and its sole purpose is to train cosmonauts and astronauts for space flight. So when I come here, there’s a certain joy from being with my Star City family. My sons were two years old when we first brought them to Star City, and one learned to walk here.

Are your twin sons interested in following in your footsteps?

They both graduated from Texas A&M [University]. One works at [NASA’s] Johnson Space Center as an engineer, and one worked for Blue Origin at Kennedy Space Center.

You’re the oldest active astronaut. How do you think your body’s going to hold up on the upcoming mission?

John Glenn went through full shuttle training at age 77. He had to fly in a T-38. He had to train for egress in the water from the shuttle and inflate his life preserver and get in the life raft. He went through it with flying colors. I do the Russian training. This last winter we did survival training, and if you think about how cold it can be in Russia, you can imagine that that was an ordeal. I did that with my Soyuz crew, so I don’t see any issue with my age on this upcoming mission.

What do you miss in Star City? Any hobbies?

Well, I make homemade beer. I like really hoppy beer. I hate to admit that during almost two years of training for this mission, I haven’t had time to brew a batch.

What advice would you give a fellow scientist who wants to become an astronaut?

Excel in whatever field you’re in. Do something that sings to your heart and do it well. Then keep applying to NASA when there are selections, and don’t take “no” for an answer!

:quality(85):upscale()/2024/07/03/025/n/1922441/4da3ba1d6685e09405e331.18212461_.jpg)