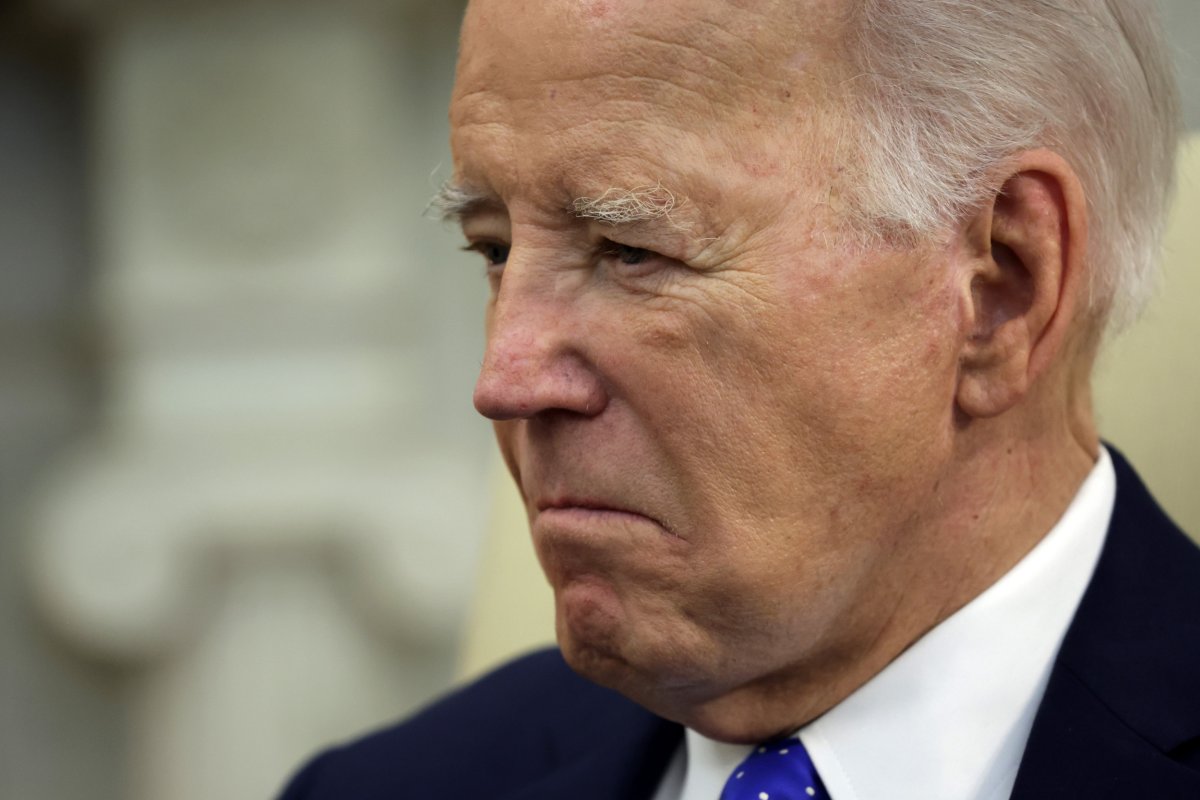

President Joe Biden is juggling significant conflicts worldwide as he tries to fight off a fierce challenge from former President Donald Trump, all the while trying to keep the U.S. out of another major war.

Members of the so-called “new Axis of Evil”—a play on former President George W. Bush‘s famous post-9/11 classification of Iran, North Korea and Iraq, broadened to include Russia and China while dropping Iraq—are engaged in both hot and cold conflicts as the presidential race picks up momentum.

In both Ukraine and the Middle East, long-time American adversaries are at war with American allies. And in East Asia, China and North Korea are threatening action against regional American partners, prime among them Taiwan and South Korea.

Charles Kupchan of the Council on Foreign Relations think tank told Newsweek there is a “broader sense of unease that current crises foster in the American electorate,” as multiple conflicts escalate and drag American forces into the line of direct fire.

DELIL SOULEIMAN/AFP via Getty Images

“It’s not as if Biden is in any way responsible,” Kupchan—who served on the White House National Security Council under former Presidents Barack Obama and Bill Clinton—added. “But there is a sense that during his watch the world has become quite unruly.”

“People don’t sleep as well at night because things seem out of whack,” he added. “On any given day of the week, you can grab the newspaper and on the front page is the front line in Ukraine, how many people died in Gaza last night, Iranian drones flying toward Israel, the United States and China at each other’s throats. You’d say, ‘I think I’ll go back to bed.'”

Particularly concerning for the U.S. and its Western allies is the cooperation between their foes. Iranian drones are hitting targets in Ukraine, while Russian oil flows in record amounts to China. Moscow and Beijing have for years been protecting Iran and North Korea at the United Nations.

U.S. European Command Commander and NATO Supreme Allied Commander Europe General Christopher Cavoli noted this month that the four nations are forming “interlocking, strategic partnerships” opposed to American national security interests.

U.S. adversaries are increasingly cooperating, if not yet directly coordinating, in their geopolitical plays. If this devolves into multiple wars involving U.S. forces at one time, even the hegemonic American military could be badly stretched.

Clouds of War

Foreign policy does not win or lose U.S. presidential elections, so the old adage goes. But wars abroad are looming large in the American national conversation as November’s election approaches, even as the country is consumed by partisan domestic issues and Trump’s myriad legal challenges.

American voters are well aware of the destabilized global picture. A December poll from The Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research found that 40 percent of respondents felt foreign policy should be a top focus of the government for 2024; around twice as many as one year previously. Twenty percent also expressed concern over direct U.S. involvement in foreign wars, versus 5 percent a year ago.

YouGov found in March that 22 percent of Americans believe it very likely that there will be another world war within the next five to 10 years, with another 39 percent saying it is somewhat likely. The sentiment is more common among Republicans (32 percent said a world war was very likely) than among Democrats (16 percent) or independents (20 percent).

The challenges for Biden—and for Trump, if he secures a second term in office in November—differ from theater to theater. But in all, America’s footprint is vital in ensuring deterrence of its adversaries.

The freeze in U.S. aid to Ukraine has underscored how vital American support is to Kyiv’s survival. President Volodymyr Zelensky said this month that his nation will lose its war against Russia unless the partisan gridlock over a $95 billion bill providing funding for Ukraine, Taiwan, and Israel is resolved.

Alex Wong/Getty Images

Kyiv finally received encouraging signals this week, with House Speaker Mike Johnson agreeing to put the package to a vote after months of stalling. But Ukraine still has a massive, costly, and difficult fight on its hands.

“Ukraine, we’re probably looking at a stalemate,” Kupchan said, even with the resumption of American aid.

Israel’s excoriating assault on Gaza has horrified many Americans, as did the Hamas October 7 infiltration attack that prompted it. The subsequent conflict has expanded to include Lebanon, Yemen, Syria, Iraq and Iran, repeatedly involving attacks on American facilities and personnel across the region. Israel’s tit-for-tat exchanges with Iran now pose the risk of a much larger and more destructive showdown.

Already, American troops have been bombarded by Iranian-aligned militias in Iraq and Syria, while U.S. warships have shot down drones and missiles fired by Tehran-linked Houthi fighters in Yemen. Last weekend, U.S. forces were reportedly instrumental in intercepting Iranian drones and missiles destined for Israel.

China, meanwhile, is regularly probing Taiwanese defenses while asserting—violently at times—its claims in the South China Sea, while North Korean leader Kim Jong Un is ramping up ballistic missile tests, determined not to be overlooked.

“On North Korea and on Taiwan, managing the problem is the mantra,” Kupchan said. “You don’t resolve it, you don’t push for resolution; you manage. And so, I think those two issues are unlikely to see any major change in the status quo.”

Bullets and Ballots

The conflicts have a domestic political dimension. The partisan division over Ukraine is clear and may become more so as Trump—who has been consistently skeptical of backing Kyiv fully—ramps up to November.

Israel’s war on Gaza has caused consternation within the Democratic Party, with progressives labeling the president “Genocide Joe” over his “ironclad” backing of Israel and failure to rein in Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu.

“In the Middle East, it’s more complicated because of the backlash among progressives and Arab Americans about loss of life in Gaza,” Kupchan said.

That backlash has come at the ballot box too. The recent Michigan Democratic presidential primary saw 13 percent of voters declaring themselves “uncommitted” to protest the White House’s Gaza policy.

On China, Biden’s apparent efforts to facilitate a thaw are also facing political headwinds, particularly given he will face a Trump who has been resolute in dealing with Beijing.

“Biden is going to feel a lot of electoral pressure to be quite confrontational with China,” Kupchan said. “Democrats and Republicans are trying to outdo each other in going after Beijing.

Celal Gunes/Anadolu via Getty Images

“The easiest thing to do is just have a rupture with the Chinese, throw the book at China, more economic tariffs, more export controls. The only problem with that is that it would intensify the estrangement that is already quite intense between Washington and Beijing.”

Biden has cast himself as the grownup in the room, a foil to a more impulsive and pugnacious Trump. This cautious elder statesman brand may work for or against the incumbent come November.

“Republicans will try and twist the knife,” Julie Norman, professor of politics and international relations at University College London, told Newsweek. “Biden had the low point with Afghanistan. I think he showed strong global leadership with Ukraine. And now he’s kind of on the back foot again with Gaza.”

“He always touted himself as the internationalist, as the statesman, very much in contrast to Trump,” Norman added. “What I’m already hearing Republicans saying is, ‘Look at all these problems in the world. When Trump was president, things were a lot calmer.'”

“It cuts both ways,” Kupchan said. “That sense of dislocation could say, ‘This is this is not a time when we want someone like Trump in the Oval Office.”

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.