Congressman David Schweikert introduced a bill that would provide a prize for the successful development of a vaccine “to prevent, treat, or mitigate opioid, cocaine, methamphetamine, or alcohol use disorder.”

The draft legislation, H.R. 7827, referred to the committee on March 26, would also require the health and human services secretary to give “priority review” for regulatory approval to any anti-drug vaccine candidate and reward the first successful applicant with public funds.

While vaccines are usually associated with providing increased immunity against pathogens, researchers are already studying whether they could use the same biological mechanisms to stop intoxicants from having an effect on the brain.

The introduction of a bill that hopes to accelerate that work comes at a time when opioids—especially synthetic ones like fentanyl—are creating a growing health crisis in the U.S. that lawmakers are struggling to find ways to deal with. According to official figures, there were nearly 107,000 overdose deaths in 2021, around 66 percent of which were attributed to fentanyl.

“I actually have a fascination with synthetic biology technology as a way to disrupt,” Schweikert, a Republican representing Arizona, told Newsweek of his motivation for the bill.

“The price of the synthetic opioid has just crashed,” he said, “and yet when you meet with the substance abuse counsellors [and] the rehab centers, they almost always start the conversation with that what they deal with today is so different… that these synthetic drugs are very, very different from the drugs we knew a decade ago, or two decades ago.”

As such, he hopes the prize he is proposing will ask the question of whether there was “an opportunity to add a tool and bring sobriety back to someone who is truly being crushed by these synthetic drugs.”

Experts say that anti-drug vaccines are not only possible, but—depending on the substance they are aiming to counteract—are potentially quite promising.

Dr. Thomas Kosten, a professor of psychiatry, pharmacology, neuroscience and immunology at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, Texas, who specializes in addiction medication and vaccines, said that jabs were possible for any abused substance except alcohol, “because making antibodies using a vaccine against alcohol would not be possible due to the small size of this molecule.”

“Any antibody against alcohol would damage many body organs and systems because alcohol occurs on many proteins within your body,” he told Newsweek.

Dr. Scott Hadland, a pediatrician at Massachusetts General Hospital and a professor at Harvard Medical School, who specializes in addiction, said that while he could not speak on the possibility of an anti-alcohol vaccine being developed, if one was it would be “really powerful” for treating alcoholism.

However, he said any producer would need to ensure “it doesn’t cross-react with other things that might sometimes be used in clinical practice, like other medications that might have similar properties to alcohol.”

Asked why he included alcohol in the bill’s text, Schweikert said there were “a couple of very credible labs still working on an alcohol version” and he was “not going to engage in my arrogance of thinking I know what the future looks like.” He added: “If it’s a breakthrough, it’s a breakthrough.”

Scientists at several American universities are currently working to develop vaccines against fentanyl, while a team in Brazil is working on a jab to curtail the effects of cocaine.

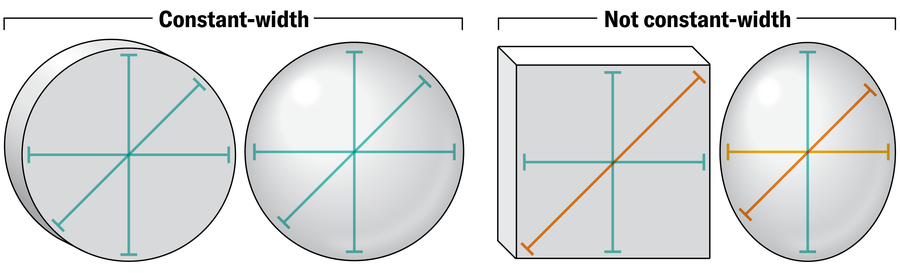

According to the National Institutes of Health, in the same way a traditional vaccine stimulates an immune response that produces antibodies capable of binding to proteins on a pathogen’s cell wall, these vaccines aim to prompt the body to produce antibodies that stick to drug molecules, making them too big to pass through the blood-brain barrier. This means they cannot cause a high or an overdose, instead being excreted by the body.

Kosten said, though, that the different drugs being targeted had so far yielded different efficacies for the vaccines being trialed. As a general rule, he said, “the more potent the drug, then the less of it that is abused and the more readily can a sufficient amount of antibody be generated from a vaccine to be a competitive inhibitor and hold the drug in the bloodstream.”

Vaccines against cocaine and nicotine have already been developed and tested on humans, but Kosten said the antibody response they produced was “not sufficiently high in many humans to be clinically useful.”

Meanwhile, vaccines against a highly potent opioid like fentanyl “is quite possible,” the addiction vaccine expert said, as “a much smaller about of antibody is needed to bind all of the fentanyl and prevent it from entering the brain.”

Alex Wong/Getty Images

However, he said that it was more difficult for candidate vaccines against heroin and other opioids to generate sufficient levels of antibodies to stop the drug overriding the blood-brain barrier “blockade” they create.

Asked to give a sense of how viable each of these potential jabs were, Kosten said one against fentanyl was “likely to be available within a few years,” while ones counteracting the effects of cocaine and methamphetamines could be viable for at least half of the people who might be given them, who he noted “currently have no FDA [Food and Drug Administration] approved medications.”

Hadland told Newsweek that even though vaccine acceptance “has been a bit of a challenge” since the coronavirus pandemic, who would want an anti-drug jab would depend partly on how long they worked for.

“Chances are the right patient is going to be somebody who is early in recovery and is at risk for relapse,” he said, adding that families and teens with parents who have struggled with addiction may want to be vaccinated “as a way to insulate them against the potential that they do try opioids and have a problem with them.”

The medical professor said that a vaccine for fentanyl would be “exceptionally helpful,” but questioned whether it would also provide protection against other, similar synthetic opioids.

There is a clear need for effective treatments for drug addiction, and a number of anti-drug vaccine candidates in development that pharmaceutical producers could capitalize on—so why is a cash prize for creating one necessary?

Schweikert said some of the laboratories working on these vaccines were not particularly well funded, but added that the “primary focus of the legislation is to speed up adoption through the FDA.”

“If there is a breakthrough, if it has the efficacy, what are the tools that a policymaker in Congress has to help it get to the market, to get to the public—to get to those who need it—as quickly and as efficiently as possible?” he explained. “So it’s a combination of change in the priority stack at the FDA and then also the additional focus I think you get when you offer a prize.”

The bill text says the prize money should be a billion dollars, subject to funding availability, but Schweikert said this was a “blank that is to be filled in.” He said he was currently speaking to vaccine researchers, potential investors and addiction non-profits about how much they think is needed to give a potentially successful jab the boost it needs.

PATRICK T. FALLON/AFP via Getty Images

A critic might argue, though, that whatever amount of public funds it turns out to be would be better spent on existing prevention and treatment programs, which stakeholders have said are vastly underfunded.

But Schweikert argued access to resources “isn’t a key issue.” Rather, the problem was that “the tools we have right now are from a previous era; they were not ready for this world of synthetic opioids.”

Hadland suggested the “devil was in the detail” in terms of where this funding came from. “Vaccines are exceptionally expensive to produce, and so I think we would not want to take those resources away from those other service we know are critical,” he said. “If there’s a way to have both, then absolutely both would be valuable.”

From a practical standpoint, because of their potential limitations, anti-drug vaccines were “not a solution that is going to work for everybody, but there is going to be a subset of patients for whom this is a good option,” Hadland said. “It’s a tool in the toolbelt; it’s not going to be a one-size-fits-all solution, but I think it’s going to be something that some people absolutely will want.”

“This is a big deal in society, and this [bill] is hopeful,” Schweikert said. “When was the last time we had something around addiction that was actually hopeful? And that’s one of the reasons for doing this: is we can’t keep approaching addition [in] the same way.”

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.