Jeff Monken sits in a brown, overstuffed leather chair just inside the door to his office at West Point. He is turned toward the Lusk Reservoir, a body of water that serves as a trivia question for incoming plebes. On command, one might be forced to tell a superior officer that, when the water is flowing over the spillway, there are 78 million gallons there. Before the football stadium was built almost a century ago, plebes know, it was 92.2 million gallons.

Coaching football at Army has obvious challenges, but Monken often chooses to focus on the silver linings. For example, his undersized roster is going to hurl itself full force against any opponent, like they did during a game in 2018 when the Black Knights nearly beat an Oklahoma team led by future No. 1 NFL draft pick Kyler Murray.

His expectations are clearly outlined: Beat the Naval Academy and Air Force (an objective he solidifies by having their logos placed on urinal scent cakes in the public restroom near the coaches’ suite). And everyone under his command has the mentality to be prepared for anything, be it white-knuckle cadet field training against active soldiers at Camp Buckner (legitimate, full-fledged war games the Black Knights players have to participate in), or a piece of West Point minutia about that pond next to their field.

Which is why, the morning of the fifth spring practice of his ninth season, he is admittedly anxious—but not terrified. Over Christmas break, Monken instructed his position coaches to phone their players and tell them something they would have considered unfathomable when they were recruited here. The Black Knights would relinquish the flexbone triple option, a scheme detractors consider archaic and one that rarely features downfield passing to control the clock and limit opposing offensive possessions. Army, Navy and Air Force all held on to a version of the system as a way to cope with the rigors of recruiting against schools that did not require its graduates to complete at least four years of military service after graduation or wake up at ungodly hours in the morning to march in formation.

Dustin Satloff/Getty Images

“What Army and what the people associated with this institution expect, and who we represent, the men and women that serve, they expect victory,” Monken says, speaking not only about football. “The American people expect the Army, when they go to fight, they expect them to win. They don’t care how they do it.”

The decision represents perhaps the largest stylistic shift in modern college football history. Aiding Monken in this pursuit are two brilliant offensive minds he plucked from relative football obscurity—a Tim Robinson–quoting, Mountain Dew–chugging former NAIA coach from Kansas who was scoring more points on some Saturdays than the Los Angeles Lakers, and a whip-smart, detail-oriented former offensive coordinator from Nebraska-Kearney who was bulldozing the rest of Division II with a streamlined run game. Together, they are trying to make Army look completely unfamiliar, despite the granite walls that surround them with a sense of permanent tradition and, in a football sense, permanent obstacles.

“They haven’t decreased the number of years that our football players have to serve in the military because we’ve won games,” Monken says. “They aren’t making classes easier. They don’t say, ‘Now that you’ve won, we know we want to make it easier for you to get that recruiting pool much bigger, so we make classes easier and we’ve come up with these three majors that the guys can get into and they can breeze through. [The players] don’t have to wear uniforms anymore. They don’t have to get up early in the morning for formation.’ All those still exist.”

Hence, the shift to something radical. To bring the ideas behind Monken’s quest full circle, he folds his hands across his chest and unwinds a metaphor familiar to the institution he’s trying to change.

“In World War I, it was trench warfare, and, I mean, that’s combative and brutal,” he says. “By World War II, we got aircraft carriers and hand grenades and we’re fighting the world a little bit differently. And in 2023, I mean, we’ve got all kinds of technology and weapons that we’re never dreamed of.

“People aren’t clamoring for us to go back to trench warfare. Find a way to win.”

This isn’t the flexbone option. This isn’t the spread. This isn’t Air Raid.

Welcome to Army’s pursuit of Modern Warfare.

The academies have been synonymous with the triple option for decades. Their roles within major college football are unique because of what their schools represent. Their identities are another link to the traditions of football’s yesteryear—executed with precision, with literal marches down the field that can take more than 10 minutes off the clock, two and three yards at a time.

The triple option from the flexbone formation—a setup that mirrors football’s early rugby scrum roots—is what Army has run under Monken for years.

It classically starts with the quarterback taking the under-center snap and multiple running backs in the backfield flanking him in condensed space. His first option after opening his body outward: hand the ball to a running back who will plunge between the tackles, determined by reading a defensive lineman. If the lineman crashes down to try to tackle the running back, the quarterback will pull the ball for options two and three—the quarterback can run the ball himself on the outside or pitch to another running back accompanying him to the edge of the formation.

There are many reasons the academies have relied on this specific option, which is seen as a form of talent equalization. They don’t churn out 320-pound offensive linemen who are bound for the NFL like Alabama or Ohio State—military weight requirements force weight cuts after a player’s career is over. There is also the academic piece that winnows down the recruiting pool, as well as the obvious service requirement after graduation.

Army has attempted to move away from it before.

In 2000, Army entered the new millennium with a new-look offense under new coach Todd Berry, who was hired to lead the Black Knights into a new era that didn’t include the under-center triple option after Army endured a few bad seasons since joining Conference USA in 1998.

The change theoretically offered Army an advantage.

“You’re looking for something from a recruiting standpoint that gives you a different advantage too, right?” Berry says. “And knowing that if I’m a quarterback—and if I’m not an option quarterback in particular—you might have a differential advantage in recruiting [over Navy and Air Force] because, all of a sudden, you got a kid that wants to go to the academies, but he is not wanting to run the option as much and he’s still wanting to be able to throw the ball around a little bit, then they might be more intrigued with Army.”

Berry ran the option when he played, but the sport wasn’t where it is now as far as offensive openness and embracing spread concepts. Over the past 20 years football has opened up and approached differently now—programs are more likely to use pass-first schemes with quarterbacks, like the Air Raid, and quarterbacks hire personal throwing coaches in the offseason. Football can be played nearly year-round in some parts of the country with the advent of the seven-on-seven circuit, which uses a common passing practice drill where linemen are removed and receivers and running backs go against defensive backs and linebackers.

Army didn’t completely reinvent the wheel under Berry, keeping some of the option principles in its offense. But the Black Knights still struggled, winning only one Commander-In-Chief’s Trophy game and posting a 5–35 record over four seasons before Berry was fired.

There were other headwinds, including offseason injuries to key players during military training, difficulties retooling the roster via transfers and the effects the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks had on recruiting. The focus of the Army experience was much more focused on the military aspect than it already was. There was a revolving door of coaches over the next 10 years after Berry’s dismissal before Army brought in Monken.

Danny Wild/USA Today Sports

Before arriving at West Point in 2014, Monken cut his teeth under option coaching legend Paul Johnson from 1997 to 2001 at Georgia Southern (an FCS power at the time). He had stints at Navy (’02 to ’07) and Georgia Tech (’08 to ’09) before going back to Southern (’10-’13) as head coach. Alabama’s ’11 national championship team gave up 341 yards in a win over Monken’s Eagles, a game coach Nick Saban famously described by saying, “They ran through our ass like s— through a tin horn, man, and we could not stop them.”

And the option has particularly worked well for Monken at Army. The average number of possessions in a college football game is around 12. Army routinely plays games with eight or often fewer. That’s less exposure for its defense and a way to defend against high-powered offenses while you have the ball by chewing clock.

Since Monken took over, Army has scored more than 17 points in regulation against Air Force or Navy only twice in 18 games. The Black Knights have won their fair share, but the low-scoring and possession football has created fine-margin games. Army has only twice won by more than a touchdown and are 9–9 against the other academies. The under bet in Army-Navy matchups hit for 16 straight seasons until 2022, when that game went to overtime. It has hit every time in Air Force–Army matchups since Monken took over.

Monken’s Army team has taken Michigan and Oklahoma to overtime and won 66% of its games in the past six seasons, including two double-digit winning seasons and two more nine-win campaigns. But while Monken has had plenty of success, running the option has become a scarlet letter at times. No offense is aesthetically pleasing when it isn’t working, but the contrast between a vertical passing game and a plodding option is particularly stark when the triple is being physically overwhelmed and a team isn’t a credible threat to throw the ball.

There was never a right time for Monken and Army to make this switch because they kept winning. Despite all the things that make it difficult to run, if the system wasn’t broken, why fix it?

Well, a few reasons—the rivalry against the academies, the growing difficulty to game plan around the scheme and something to prove.

Basing an entire offensive philosophy change on two games may seem odd, but the academy games are omnipresent if you spend time around the Army program. The first thing you see when you walk into Army’s football offices are a wall of mannequins wearing the Nike-designed uniforms specifically worn in the Army-Navy game. Army’s wins in the Commander-In-Chief’s Trophy games play on a wall-mounted TV behind them. Monken ends just about every conversation by saying “beat Navy,” and the equipment trailer parked outside Michie Stadium has “Sing Second” on the back of it (an ode to the Army-Navy tradition where both teams stand for each alma mater to be played, with the loser’s being played first).

Danny Wild/USA Today Sports

Army’s rivalry with Navy goes back to 1890, and Air Force entered the fold in 1959. The three have competed against one another for the Commander-In-Chief’s Trophy since 1972. Air Force has won it 21 times, Navy 16 and Army only nine. Monken’s Black Knights have, however, won it in three of the past five years and Army’s 2017 win was its first since 1996.

“Those games are like if you said, ‘O.K., two guys are going to fight. You each get a sledgehammer and you hit him as hard as you can with a sledgehammer, and then he gets to hit you back with his sledgehammer, and then you hit him back with a sledgehammer, and the last one standing wins,” Monken explains. “I’m not saying this offense is all of a sudden going to blow the doors off of it and we’re going to score all these points. I have no idea, but I know we need to give ourselves a better chance to win the football game on offense and score more points.”

Running the under-center option was Army’s ace in the hole for the other 10 games on their schedule, but its uniqueness can make it tough on them to game-plan. There are times when Army players will take the field expecting to see one thing and then needing to adjust on the fly totally because the defense has lined up in something they didn’t and couldn’t prepare for. The new offense gives the Black Knights a chance to see defenses defending something similar in other games. Since so few teams run the option, it can be difficult to find film of an opponent defending it.

Monken is as sharp as they come, but coaches don’t make hires. Athletic directors have to answer to donors who are ready to turn up their noses at even the hint of an option system. The option could win games with Alabama’s talent, but it would certainly lose the press conference and many recruiting battles.

“Not for the program, but for me professionally, I think there are a lot of people out there that don’t think option football coaches understand real football,” Monken says. “Option football is far more complex than anything anybody else is doing.”

For all those reasons, Army still stuck with the option. But two days before its 2022 spring game, an NCAA ruling forced the Black Knights’ hand.

Monken found out via email that the organization’s playing rules oversight panel approved a proposal banning players from blocking below the waist outside the tackle box, allowing only lineman and stationary backs to do so inside the box on their initial blocking movement. The panel cited player safety as a reason, but Monken wonders whether that was the real reason and says tackles below the waist are much more dangerous that blocks, and there’s no way you’d outlaw them.

“People don’t want to have to defend it,” Monken says. “They don’t want to have to teach the cut block. It eliminates having to teach that fundamental skill. It eliminates them having to defend the offense because it’s going to be really difficult to run this offense the way we ran it without being able to block below the waist and those linebackers in the box that are screaming to the perimeter that you can’t cut-block anymore.”

Marvin Gentry/USA Today Network

Would this rule have changed if Texas, Georgia, Clemson and Ohio State ran the flexbone? It’s doubtful college football’s biggest fish would have been O.K. with that, but the rule affects only a small percentage of FBS’s 133 schools.

Monken says he was surprised at how much the new rules limited the offense.

“You can’t use a tackle and loop them and cut [defenders],” Monken says. “You can’t run the fullback out of the back field and cut. You can’t use the slot back and load them and cut them. All those blocks were effective from keeping the linebackers from getting out there, and everything we do is full flow under center.”

Monken had to go back to the drawing board, and he thought back to a chance meeting with a football mind that, as he described, was “smart as s—.”

It was back in 2017, when Monken was at the American Football Coaches Association (AFCA) conference. For most NCAA head coaches, it is a brief exercise in gladhanding, and they rarely attend talks given by rising coaches. But Monken walked up to the front row of a seminar called “Coyote Football: Evolution of the Run Game,” presented by Matt Drinkall. Drinkall was the coach at Kansas Wesleyan, an NAIA school in Salina. Drinkall was, as Monken puts it, “Scoring like a pinball machine.”

In one season, Drinkall’s team set school records for points in a game (83), points in a half (69), points in a single quarter (49), total touchdowns, rushing touchdowns, passing touchdowns and wins. The Coyotes were putting up 54.3 points and 530 yards per game and more than seven yards per play.

Monken opened up his notepad.

The 20-slide presentation focused on simplicity, spacing, speed and the maximization of assets. It was, for the time, radically ahead of the curve. Drinkall liked to be able to run and pass out of every formation and personnel grouping. If his kids’ heads were moving (looking around trying to figure out what was going on) then their feet wouldn’t be.

The final slide was prophetic, though only Monken knew it at the time. Drinkall wrote: “Let me know if we can help you in any way.”

So began a courtship.

Matt Drinkall’s office looks like the best part of a Hot Topic or Spencer’s Gifts.

There are Funko Pops everywhere and a poster of Mount Rushmore with the presidents’ heads replaced by legendary professional wrestlers. Over the Bluetooth speaker plays “Man of Constant Sorrow” from the O Brother, Where Art Thou? soundtrack. He photoshopped the head of Karl Havoc from the sketch television show I Think You Should Leave onto the body of tight end Joshua Lingenfelter. (Tight end meetings at Drinkall’s house would quickly devolve into binge sessions of watching the show.) There is a joke within the Army football facility that one needs a ticket to get into Drinkall’s room due to demand.

A few feet in front of his desk is a small flat-screen television where Drinkall calls up film of the most dominant offenses in the NCAA. Long ago, while a wide receiver at Iowa, he would wonder why everything had to be a muddy drudge. Now, his canvas is blank. One of Drinkall’s unique gifts is an ability to download mass quantities of game information and immediately apply it to his own set of personnel. It will space out the defense so their most important offensive player—the quarterback—isn’t mashing into a human sausage grinder on every play.

“Now [when we run our quarterback], you’re running into five- and six-man boxes instead of 10-man boxes,” Drinkall says over a Diet Mountain Dew, referencing the smaller number of defenders Army will have to face crowded against the line of scrimmage. “That’s half as many guys and the guys [in there] are smaller.”

Army Athletics

To complete the offensive coordinator tandem after hiring Drinkall in 2022, Monken brought in Drew Thatcher, the quarterbacks coach and offensive coordinator at Nebraska-Kearney. Like Drinkall’s, Thatcher’s offenses were lighting up high-level football in the Midwest, with the Lopers consistently finishing as one of Division II’s best rushing teams. In his first year as Nebraska-Kearney’s offensive coordinator, the team rushed for 4,115 yards and 45 touchdowns, both school records.

Monken dreamed of fitting Thatcher’s powerful running game into Drinkall’s vision of a spaced-out offense that draws defenders away from the line of scrimmage. He had Drinkall call Thatcher and interview him as if he were the coach for more than three hours. Not long after, he was on his way to West Point.

As a kind of yin to Drinkall’s yang, Thatcher’s office is sparsely decorated. Soft Christian music plays from a speaker on his desk. His lone decorative feature is a coffee mug that reads, “No one cares. Work harder.”

Together, throughout the facility, they are a complementary force. Thatcher transforms on the field, throwing his body into drills. On one particular freezing March afternoon, he was in the face of his wide receivers, belaboring a point that is still new to the team’s skill position players. Thatcher was pointing to the defensive backs, reminding the receivers that “YOU scare THEM.”

Drinkall, meanwhile, perches and analyzes. In one meeting shortly before practice, he sits a few feet from the projector screen. The linemen are self-scouting, standing at the front of the room and critiquing their teammates’ performances from practice film in an effort to cement new footwork that comes with the scheme. He’ll periodically cut through the chatter with a point that brings the room to equilibrium.

They do not flinch at the scope of this rebuild. For certain position groups, the mechanical changes, throws and concepts are like learning an Android after years of using a rotary telephone. Yet, they are clawing for the day’s evidence of concrete progress.

There will be carryover from what Army was doing before, but the most important aspect is the spacing in the offense. Drinkall cycles through Alabama film from 2020, calling out the formation names that Army has for what the Tide are lined up in on the screen.

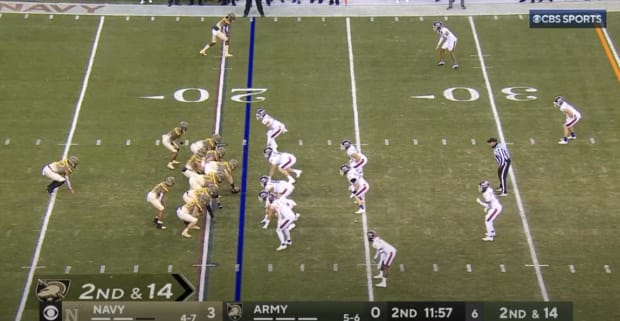

Where the Black Knights used to look like this …

YouTube

… Army will now look much more like this:

YouTube

Army’s base run will be inside zone like the vast majority of college offenses, with the ability to pull linemen to add wrinkles to the run game like power and counter (referred to as gap scheme). But the zone has afforded smaller lineman to get an advantage as it did when the Denver Broncos rode it to Super Bowls in the 1990s. Expect Army to have a run game whose concepts mirror Urban Meyer’s smashmouth spread while he coached at Utah, Tim Tebow’s Heisman- and national-championship-winning offenses in the mid-2000s, and Rich Rodriguez’s West Virginia.

The Black Knights have options, but aren’t running what you’d refer to as the option. Army isn’t handing the ball to a beefy fullback from under center, but it is still running an offense with multiple ways to attack a defense. When you turn on the TV on any given Saturday and you watch a college football team run the now-ubiquitous run-pass option plays that are essentially multiple plays packaged into one, you’re watching option football. When you see a quarterback and running back perform the zone read-mesh point action only for the quarterback to pull the ball and throw to a bubble screen on the edge, you’re watching option football.

Replacing the pitch element of the triple option with a screen pass to the perimeter uses more space on the field and is why many coaches view screens as an extension of the run game. The lines of what an offensive play is are being blurred at the college level.

“If the O-line is blocking a run play, who cares how or where the ball gets distributed?” Drinkall says. “It’s a run play. You’re just pitching it the other way. If we run zone [blocking] this direction and pull it and distribute the ball out here, whether it’s like this, is a pitch where it counts rushing yards or it’s a tight end running an out route you throw it to them, who cares? So, what has happened [in modern football] is, outside run plays, quick passing games and play-action passes that were very, very siloed off before, are all being completely blended together.”

When Army players are on the practice field now, they do what was once unthinkable: a seven-on-seven drill.

“We really only did it so the defense could defend passes,” Drinkall says. “So now we’re up to 15 to 20 minutes a day. So, that’s been a major shift. We’re working pass protection now by the O-line. So that wasn’t a thing that was going on here before.”

Army has to drill down on many aspects of this offense. Army offensive linemen are blocking more upright and working to the second level more often. Every offensive lineman works on snapping with a new so-called “dead-arm technique,” where the entire arm works as a lever to deliver the ball to the quarterback in his new shotgun alignment (preferably on the right breast plate for right-handed signal-callers). This style takes the wrist out of it and can limit the chances of an errant snap.

A different period of practice has quarterbacks, running backs and receivers working on their pitch relationship. There was a pitch option on virtually every play in Army’s old offense where the pitch happened much faster from under center. Now, it’s more stretched out and takes up more space on the field, and the pitch has to go further than it used to.

The real beneficiaries are receivers, who are no longer left to just come from their positions and block.

“Every prospect I meet thinks, I’m going to play in the NFL. So they get told, ‘Well, you can’t go [to Army] because you never pass block. You can’t go there as a lineman. You can’t go there on defense because all you’ll ever practice against every day is against the option. You never practice against regular football,’” Monken says. “They try every way they can, but kids listen. They don’t think, Well, this college coach, he’s not going to lie to me or give some kind of story. So I think it’ll change.”

It’s hard to change on a dime for a school that effectively can’t take players from the transfer portal (any student who transfers into West Point starts as a Day 1 freshman academically) and will have to deal with UTSA, Syracuse, Coastal Carolina and LSU. But their mindset can be seen within the schedule posted on the wall in a team meeting room. There are 12 lines, with 12 dates and the location of each team on their schedule, but the opponent listed is the same: Army.

Patrick Oehler/Times Herald-Record/USA Today Network

Bryson Daily, Army’s quarterback, removes his upper padding after practice and shows a pair of visitors a rash developing in the shoulder area where the elastic from his jersey meets the skin of his throwing shoulder.

He is chucking the ball so much in practice that his skin is becoming irritated. It is a common malady for many quarterbacks (he’ll learn that the remedy is an undershirt). But the junior is experiencing it for the first time. If there is real physical evidence for the rigors that come with such an evolution—actual, Darwinian scarring—it exists right there. Daily and his receivers wouldn’t have it any other way.

“One of my [receiver friends on the team] came to me and said, ‘Man, football’s fun again,’” Daily says.

Army’s goodbye to the past is a bittersweet one. Monken was almost poetic about what he was leaving behind. Army’s offense was like its own battle uniform. It telegraphed something unspoken. It embodied its cross to bear, for daring to still play college football in an NCAA that has simply become Roger Goodell’s feeder league.

“I’ll miss the confidence of lining up under center and the fullback is five yards [behind the quarterback],” Monken says. “He weighs 250 pounds, he’s handed the ball, and you just smash people and knock people off the ball and double-team blocks and gain three yards, and sometimes there’s just nothing the defense can do about it.”

He will also miss manipulating future NFL defensive players with his band of misfit toys. He will miss how the offense yielded so many wide-open deep shots in the passing game, yanking the pants down off a real-deal defense in front of a packed house. He’ll miss watching Saban’s postgame press conference, where the grumpy old ball coach was asked about a switch route Monken hit him with for a score and said, “I just hope I never see that again.”

Such is life in Modern Warfare. Maybe you give back a little of the romance, a sacrifice for the trappings of cold convenience.

But if there is any place that can continue to breathe some life—real, joyous, backyard football life—into college football, it’s at Army. Deep into the night, hours into a day that always ends with no sleep, hours before they are up at the crack of dawn marching again, they are out here trying to write a sequel to a song we thought we knew by heart. They are shoulder-bumping and piling on one another in the middle of Week 1 of spring practice. If there is any strain, any desire to turn back now, it is drowned out under true happiness.

You can hear them holler over all 78 million gallons of the reservoir, fit with the knowledge that they will leave a place built on assimilation unlike it ever was before.