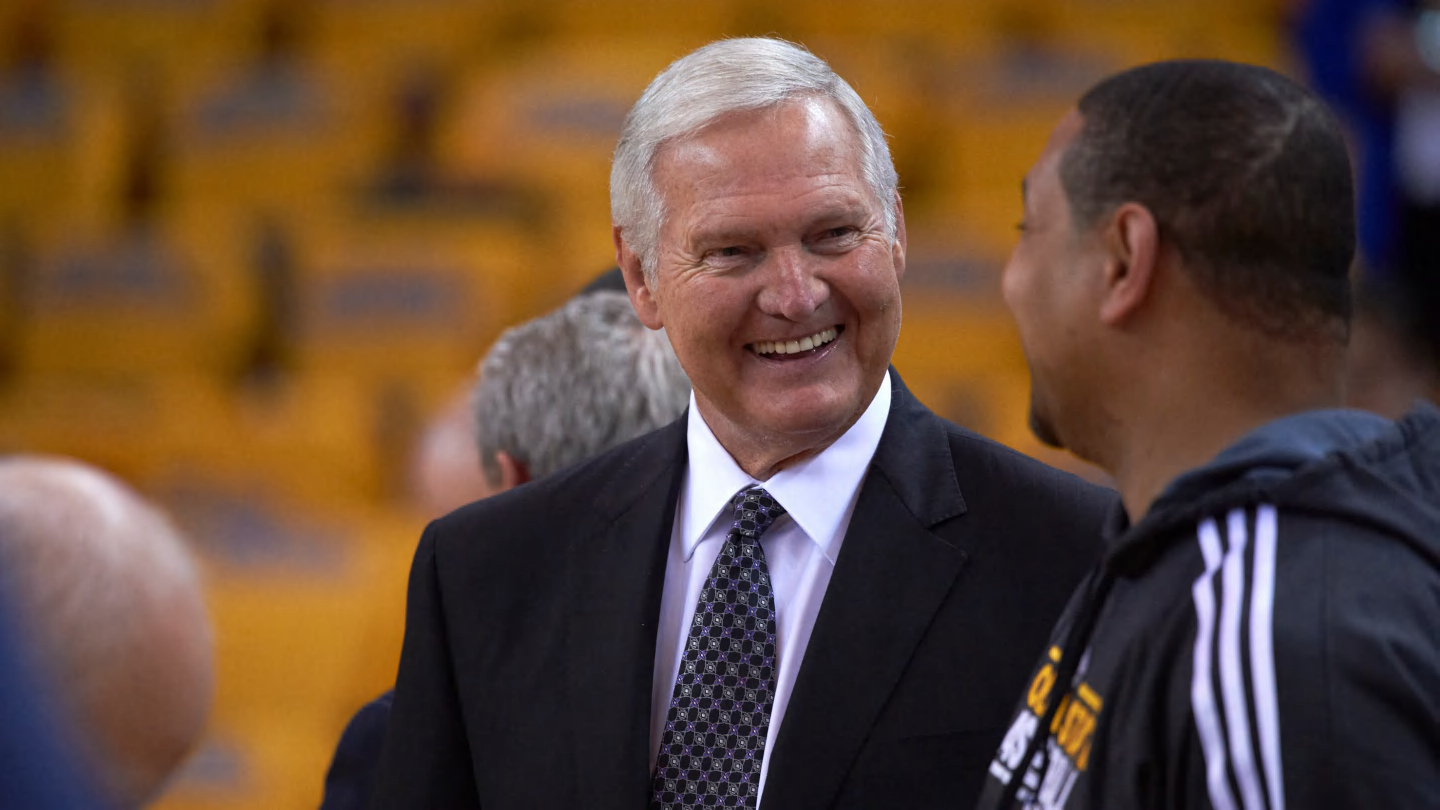

At an age when most players of his generation were long gone from the game, cursing it from afar and proclaiming how much better and purer it was when they played, Jerry West was still in the thick of the action, making decisions, talking to players and generally relating to young men whose great-grandfathers might’ve watched him play live.

“Staying relevant for all those years,” says Ryan West, a former scout for multiple NBA teams and the fourth oldest of West’s five sons, “may have been my father’s greatest legacy.” And that is said about a man who was—and possibly will be for eternity—quite literally the symbol of the NBA. He was months away from being enshrined in the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame for an unprecedented third time, as a Contributor, which recognized his primacy as a general manager. He is also in the Hall as a player and as a member of the 1960 gold-medal-winning U.S. Olympic team, which he co-captained with Oscar Robertson.

West, aka The Logo, died Wednesday at the age of 86 in Los Angeles, where he has lived almost continuously since 1960, the year the Minneapolis Lakers drafted him out of West Virginia University and immediately thereafter moved to the West Coast. “That was the first of many breaks I got,” West once said. “I was a small-town kid, but I found a home in L.A.”

Still, you could never quite get the Mountain State out of the boy—he chose West Virginia as his burial spot, and it’s anybody’s guess how many mountain staters will turn out when he is laid to rest. West is arguably the most enduring personality from a state that also produced Don “Barney Fife” Knotts and retired football coach Nick Saban.

West was still active as a consultant for the Los Angeles Clippers when, over the last few months, he began having difficulties with congestive heart failure. He was recently hospitalized for three weeks but was released and died at home. He had experienced atrial fibrillation (afib) for many decades.

Though West also served as general manager of the Memphis Grizzlies and was a much-consulted consultant with the Golden State Warriors and most recently the Clippers, it was with the Lakers that West will be forever associated. He was that rare sports personality who achieved fame—indeed, immortality—both during his playing career and after it had concluded.

West was not the game’s first white superstar, a distinction that belongs to Minneapolis center George Mikan and Boston Celtics guard Bob Cousy. But they had played when the game was largely the domain of white players, while West came along when the NBA was starting to be dominated by Black players. “Zeke from Cabin Creek”—more on that misnomer later—became the touchstone reference for the Alpha Caucasian. Comedian Richard Pryor even had a bit about West. “You brothers better get serious,” Pryor would say from stage, “because this white guy is kicking your ass.”

Still, for the first several years of his career, West was only the second-most important Laker, and, in fact, only second among 1960 draft picks. “Oscar [Robertson] was much more prepared than I was coming into this league,” said West, of the Big O with whom he will be eternally twinned. And on his own team, West was in awe of the talents of Elgin Baylor, a prolific scorer and rebounder who should be on anyone’s list of the NBA’s early immortals.

But by his third or fourth season in L.A., West had made his own rep. Tougher than a Cossack, blessed with natural talent and motivated by a killer personality, West was even, in a strange way, Hollywood. His size, a legit 6’3″ with a massive wingspan, surprised people when they met him. He didn’t have movie-star good looks but, rather, the face of a hard extra, someone who tumbled down stairs, dusted himself off and went back looking for more. West’s penchant for getting his nose rearranged—he estimated that it was broken nine times—only added to his allure.

Still, the West-Baylor combo could not win an NBA title, and the Lakers’ six losses to the Celtics in the decade of the ’60s haunted West throughout his career, and, to some measure, until the end of his life. “My life and career always tilted toward the tragic side,” West and co-author Jonathan Coleman wrote in West by West: My Charmed, Tormented Life, his best-selling 2011 memoir.

To a large degree, West never got over feelings of insecurity stemming from what he described as an emotionally deprived boyhood in West Virginia, the result of a distant relationship with his father, Howard, a union electrician in the coal mines. West was also deeply affected by the death of his older brother, David, who was killed in Korea. “He was my hero,” said West, who was born in the small burg of Chelyan. However, the West family picked up its mail at the infinitely more rural-sounding burg of Cabin Creek, and it was teammate Baylor who hung the nickname of “Zeke from Cabin Creek” on West early in his career.

West didn’t care for the nickname, but in some ways he clung to that rural persona, rarely venturing into controversial political territory, something he came to regret. His Olympic co-captain Robertson was among those who led the fight to improve labor conditions for players, and, late in life, West said wistfully: “I always admired him for that.”

But though West professed unease in the spotlight, he never left it much. He was an immensely popular player and was rarely blamed for the Lakers’ repeated failures to get to the finish line. Lakers fans loved him and opponents’ fans loved him, too. “So many times someone would come up and say, ‘I was a Celtics fan but I loved your dad,’ ” says Jonnie West, Jerry’s youngest and the director of player programs for the Warriors. “That’s when I realized how popular my father really is.”

A branding consultant named Alan Siegel admired West, too. In 1969, Siegel was hired by the NBA to come up with an official logo for the league. He settled on a photo that showed the silhouette of a player dribbling to his left. It was clearly West, but the league never wanted to admit that it was modeled after a single player. “Tell you the truth, it always kind of embarrassed me,” said West, who for decades was coy about it himself, and even in recent years made unconvincing claims that he “wasn’t sure it was me.”

Some of West’s frustration with all those losses to Boston was abated during the 1971–72 season when the Lakers, who by now had acquired Wilt Chamberlain by trade and lost Baylor by retirement (nine games into the season), ran off an astounding regular-season record that still stands—33 straight wins—and disposed of the New York Knicks in six games to win the franchise’s first title in Los Angeles. Still, even that was bittersweet for West, who did not play particularly well in the postseason, which was dominated by the defensive-oriented play of Chamberlain, the NBA Finals MVP. It was West’s fate to be most dominant when the Lakers lost.

West retired early in the 1973–74 season, an All-Star in every one of his 13 complete seasons. At that time, only Chamberlain (30.1) and Baylor (27.4) had averaged more points per game than West (27, who is still eighth on the all-time list).

West returned to coach the Lakers for three seasons but found that the profession did not suit his perfectionist ways. But in 1982, he found his true calling, moving into the general manager position when Bill Sharman, West’s coach during his lone championship season, became team president. (The move was made by new team owner Jerry Buss not only to accommodate West but also because Sharman had a throat condition that made it difficult for him to speak.)

It was in that GM position that West made himself into a legend a second time, collecting the “Showtime” pieces around Magic Johnson and Kareem Abdul-Jabbar that led to five championships in the 1980s, then keeping the Lakers competitive through the mid-’90s until he drafted Kobe Bryant and landed Shaquille O’Neal in a free agent deal that resulted in a Laker three-peat at the beginning of the century.

“It wasn’t just Jerry’s ability to see a great player, it was his ability to see how much better that player was going to be,” says Geoff Petrie, who was the general manager of the Sacramento Kings from 1994 until 2013. “And Jerry was not only great at finding the great ones; he knew how to put the pieces around the great players, which is sometimes just as important.”

Despite L.A.’s success, West was rarely happy, for that was his nature. He fell out with Showtime coach Pat Riley (his best friend when they were teammates on that 1972 Lakers championship team), chafed under Buss’s refusal to make him the highest-paid GM in the league and never did get along with Phil Jackson when the triangle offense Zen Master was hired to coach the team.

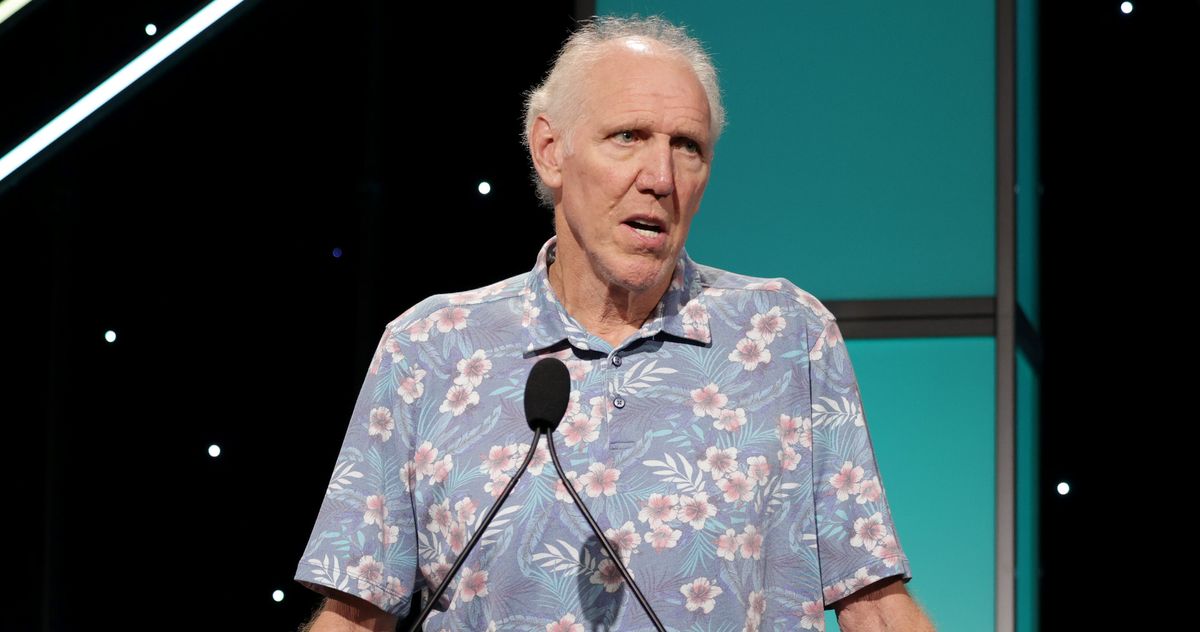

Yes, many of the stories about West—and how many are there about a guy who’s been a known quantity since 1960?—will be about the web of gloom that sometimes seemed to envelop him, even crush him. But there was another side. Few people in the history of any sport had the knowledge and magnetism to gather so many players from so many generations into his orbit. The extraordinary number of condolences included messages from Michael Jordan and LeBron James, neither of whom played on teams under West. Jordan referred to him as being like “a big brother” and James said he will “miss our convos.” The touch West had on his masterful stop-quick jump shot was one thing, but his ability to touch multitudes in this game will be his enduring legacy.