Voyager 1 Is Back! NASA Spacecraft Safely Resumes All Science Observations

NASA’s venerable Voyager 1 spacecraft has resumed normal science operations with all four functioning instruments for the first time in more than six months

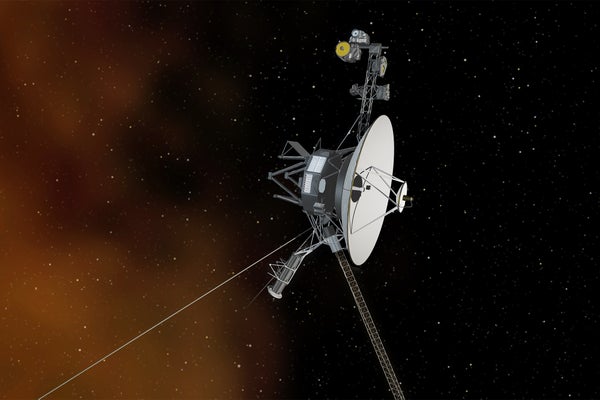

Artist concept of Voyager 1.

NASA’s beloved Voyager 1 mission is back to normal science operations for the first time in more than six months, according to agency personnel. The announcement was made after NASA received data from all four of the spacecraft’s remaining science instruments.

The venerable spacecraft launched in 1977 and passed into interstellar space in 2012, becoming the first human-made object to accomplish that feat. Today Voyager 1 and its twin, Voyager 2, are NASA’s longest-running missions. But the title has been challenging to hold on to for spacecraft that were designed to operate for just four years. The aging probes are stuck in the deep cold of outer space, their nuclear power sources are producing ever less juice, and glitches are becoming increasingly common.

Most recently, Voyager 1 faced a communications issue that began in November 2023. “We’d gone from having a conversation with Voyager, with the 1’s and 0’s containing science data, to just a dial tone,” said Linda Spilker, Voyager project scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), of the spacecraft’s troubles in an interview with Scientific American in March.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

After more than six months of long-distance troubleshooting—Voyager 1 is more than 15 billion miles from Earth, and any signal takes more than 22.5 hours to travel from our planet to the spacecraft—mission personnel have finally coaxed Voyager 1 to gather and send home data with all its remaining science instruments, according to a NASA statement.

The fix required months of analysis to track the issue to a particular chip within the spacecraft’s flight data subsystem. That chip’s code couldn’t be relocated in one fell swoop, however, so mission personnel split the information chip into chunks that could be tucked into stray corners of the rest of the system’s memory. NASA began implementing the new commands in April. And in May the agency directed the aging spacecraft to resume collecting and transmitting science data. Voyager 1’s plasma-wave subsystem and magnetometer bounced back immediately. Its cosmic-ray detector and ow-energy-charged-particles instrument required additional troubleshooting, but both are now finally operating normally, according to NASA.

And although the spacecraft is back to normal operations, the work isn’t quite over. To complete spacecraft recovery from the glitch, mission personnel still need to resynchronize timekeeping software across Voyager 1’s three computers and to maintain the recorder for the spacecraft’s plasma-wave instrument, in addition to completing smaller tasks.

Taken together, Voyager 1’s four remaining instruments offer scientists a precious glimpse of interstellar space. Voyager 1 and 2 are the only two operational spacecraft to cross out of the heliosphere, the bubble of charged particles that marks the influence of the sun across the solar system. This bubble grows and shrinks as the sun passes through its 11-year activity cycle. Inside the heliosphere, space is dominated by particles of the solar wind, while outside of it, cosmic rays reign.

Scientists never dreamed that Voyager 1 would be able to taste these exotic particles. Its primary science targets were Jupiter, Saturn, and the latter planet’s rings and largest moon, Titan—all of which the spacecraft flew past within a few years of its launch. But the mission has survived every challenge to continue trekking through the solar system and into interstellar space, informing scientists about its environment along the way.

:quality(85):upscale()/2024/04/04/954/n/1922441/f8a5834c660f218dda4f47.34950344_.jpg)