August 20, 2024

3 min read

New Insights on Dinosaurs, Pain and Carbon Capture

How we’ll learn more about dark matter, quantum gravity and substitutes for lab animals

Scientific American, September 2024

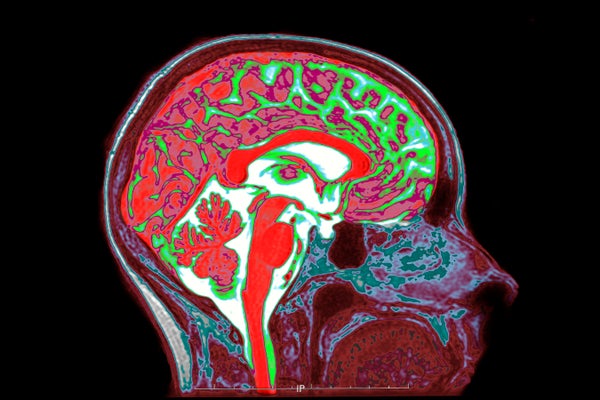

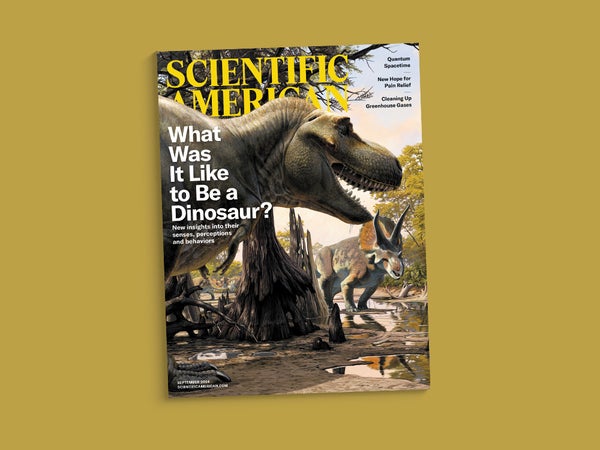

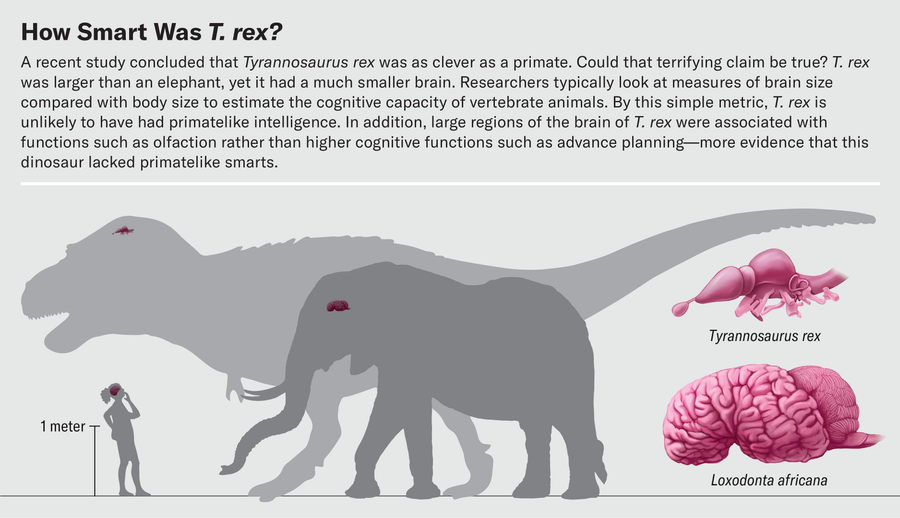

A 1974 essay called “What Is It Like to Be a Bat?,” which is still taught in cognitive science and philosophy courses, argues that we can never completely understand another organism’s consciousness. That may well be, but we’re getting closer, and not just for bats. New research combining neuroscience with advanced fossil scanning is revealing the size, shape and specializations of dinosaurs’ brains, which can tell us a lot about what it was like to be a dinosaur. In this issue’s cover story, evolutionary biologist Amy M. Balanoff and paleontologist Daniel T. Ksepka reconstruct the perceptions and actions of Tyrannosaurus rex, Triceratops, Stegosaurus, and other classic characters. I hope you enjoy the lush and dramatic illustration by Beth Zaiken; see our Contributors column for more about her paleo-art career.

We at Scientific American have been fascinated for decades by the discovery that dark matter exists and the subsequent search for its true nature. At the beginning, as physicists Tracy R. Slatyer and Tim M. P. Tait recall, scientists came up with quite a few great hypotheses, some of which linked dark matter to other puzzles in physics. But now most of the easy answers have been eliminated, as well as many of the not-easy ones. Physicists are expanding the search, and to get a sense of the search space, please delve into the graphic by Tait and senior graphics editor Jen Christiansen. As the authors write, “the scope of the problem is both intimidating and exhilarating.”

A long-awaited class of pain relievers could become available soon. One in five adults in the U.S. suffers from chronic pain, and many more people endure temporary, acute pain. Over-the-counter medications can’t provide enough relief, and opioids have dangerous side effects. The new drugs, one of which has made it through several stages of clinical trials, block sodium channels in nerves, dampening pain signals before they reach the brain. Health writer Marla Broadfoot discusses this approach and what it could mean for people in pain.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Today new pain medications and other drugs are tested in animals before they go to human trials. But laboratory models that are more efficient and accurate are being designed to replace at least some rats, monkeys, rabbits, and other guinea pigs. As author Rachel Nuwer explains, organ-chip technology mimics human cells and tissues; organoids made from a patient’s stem cells can show signs of their pathology in a dish; and engineered organs can make it easier for scientists to study rare diseases.

Last year was the hottest year on record, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s 175-year climate history. The average temperature for 2023 was 0.15 degree Celsius hotter than the second-hottest year, 2016, and that margin is itself a record. We have to do something; we have to do a lot of things. Direct air capture would suck carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere, and it’s getting plenty of private and public investment. Journalist Alec Luhn shows how it works, how it could scale up, why it seems promising, and why we should be wary of some of the claims that it will fix climate change.

Einstein’s general theory of relativity explains almost everything there is to know about gravity. But it doesn’t explain the quantum nature of spacetime, and physicists have been trying for decades to understand quantum gravity. Now a proposed series of lab experiments could finally point us in the right direction, as philosopher Nick Huggett and physicist Carlo Rovelli spell out, with illuminating graphics, again from our very own great Jen Christiansen.

:quality(85):upscale()/2023/07/31/951/n/1922794/a883fa7d64c82caebc8000.45711879_.png)

:quality(85):upscale()/2023/06/22/889/n/1922729/13f877246494acfec211e5.50616134_.jpg)