August 20, 2024

4 min read

Many Older People Maintain and Even Gain Cognitive Skills

Contrary to stereotypes of the doddering elderly, research shows that half of people older than age 70 stay mentally sharp

As I watched my parents’ generation reach their 80s, I was struck by the dramatic differences among them. A handful suffered from dementia, but many others remained cognitively sharp—even if their knees and hips didn’t quite keep up with the speed of their thoughts.

That observation runs counter to prejudices about aging, which were highlighted early in the 2024 presidential race between elderly candidates, but these biases permeate society in general. “The belief about old people is that they’re all kind of the same, they’re doddering, and that aging is this steady downward slope,” says psychologist Laura Carstensen, founding director of the Stanford Center on Longevity. That view, she says, is a great misunderstanding.

Instead research highlights the very differences I noticed. In our 40s, most people are cognitively similar. Divergences in cognition appear around age 60. By 80 “it’s quite dramatically splayed out,” says physician John Rowe, a professor of health policy and aging at Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health. Yes, there will be a group diminished by dementia and cognitive decline, but in general the 80-somethings “include the wisest people on the planet,” Carstensen says.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Focusing on only those with poor brain health misses more than half the population. Rowe led research showing that in the six years after turning 75, about half of people showed little to no change in their physical, biological, hormonal and cognitive functioning, whereas the other half changed quite a lot. A longer-term study followed more than 2,000 individuals with an average age of 77 for up to 16 years. It showed that the three quarters who did not develop dementia showed little to no cognitive decline.

Some of this is related to genetics. Studies of successful aging have shown that genes account for 30 to 50 percent of physical and cognitive changes. But factors like a healthy way of life and good self-esteem are also consequential. So to an extent, Rowe says, “this is really good news because it means that you are, in fact, in control of your old age.”

Research has also busted the myth that there is no upside to aging past 70 or so. “We have found very clearly that there are things that improve with age,” Rowe says. The ability to resolve conflicts strengthens, for instance. Aging is also associated with more positive overall emotional well-being, which means older adults are more emotionally stable than younger adults, as well as better at regulating desires.

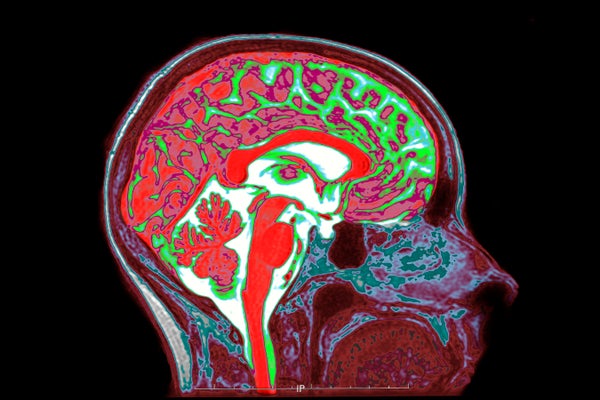

The normal aging process does bring changes to the brain, says Denise Park, a neuroscientist at the University of Texas at Dallas. There is some shrinkage in the frontal lobes and some damage to neurons and their connections. Cognitive processing slows down. Yet that slowdown is usually on the order of milliseconds and doesn’t always make a meaningful difference in daily life. And to compensate, older people activate more of the brain for tasks such as reading. “Older adults will often forge additional pathways” for particular activities, Park says. “Those pathways may not be as efficient as the pathways that younger adults use, but they nonetheless work.”

The cliché that age brings wisdom is also backed up by science. “Where older adults really shine is in their knowledge,” Park says. If you think of the brain as a computer, “there’s a lot more on the hard disk,” she says. Older adults can draw on their experience and often have much better solutions to problems than younger adults. “Frequently that can give them an edge that is unexpected,” Park says.

That edge shows up in decision-making and conflict resolution. One study asked several hundred people to read stories about personal and group conflicts. The study, published in 2010 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA, found that participants older than 60 were more likely to emphasize multiple perspectives, to compromise, and to recognize the limits of one’s own knowledge. Carstensen’s observations reinforce these conclusions. “The decisions that people make as they get older tend to be ones that take into consideration multiple factors and multiple stakeholders,” she says. Older adults are less likely than younger people to see the world in stark black-and-white terms. Carstensen says that when responses in such studies are rated by observers who don’t know how old participants are, the older people’s answers are seen as wiser.

Such wisdom may be the result of a gradual shift in perspective, Carstensen says. As we age and become more aware that time is short, we focus more on the positive. A meta-analysis combining data on more than 7,000 older adults found they were significantly more likely than younger adults to lean toward the positive versus the negative when processing information.

The COVID pandemic has showcased this contrast. In a 2020 survey of nearly 1,000 adults, Carstensen and her colleagues found that the older adults were better able to cope with the stresses of the pandemic, despite being one of the groups at highest risk of health complications and death.

The fact is that different parts of the body can age at different rates in the same person. Someone who stumbles on stairs may do so because of creaky knees, not cognitive decline. If someone has a healthy brain, age alone might be considered a definite asset. “If you were to take the kinds of decisions presidents make and compare them to the kinds of skills older people have versus younger people, I put my money on older people,” Carstensen says.

This is an opinion and analysis article, and the views expressed by the author or authors are not necessarily those of Scientific American.

:quality(85):upscale()/2024/05/21/843/n/49351759/1b28be85664cf28ef0ec06.39361637_.jpg)

:quality(85):upscale()/2024/03/28/869/n/3019466/114b9e306605ca507c8c91.74296288_.jpg)