Space is getting crowded, with junk. Essential satellites delivering navigation, weather forecasts, the Internet and other services face this threat daily. Old rockets, decaying spacecraft and human operations in space leave behind orbital debris that increasingly threatens collisions, menacing a growing space economy. A decade ago the film Gravity dramatized the consequences of space pollution, with an avalanche of space junk sweeping across the sky to batter everything in orbit, including its astronaut hero. We haven’t done anything serious about it since then.

NASA defines space junk, or orbital debris, as “any human-made object in orbit that no longer serves a useful purpose, including spacecraft fragments and retired satellites.” A 2009 incident, when the U.S. communications satellite Iridium 33 collided with the defunct Russian military satellite Kosmos 2251, serves as a good reminder of its growing threat. That single collision created more than 2,200 pieces of new debris measuring over five centimeters in diameters, according to NASA.

More of these collisions are coming. In February an abandoned Russian satellite passed within about 20 meters of a NASA satellite. SpaceX’s Starlink satellite constellation alone carried out more than 25,000 collision-avoidance maneuvers from December 2022 to May 2023. And even on Earth, space junk is a problem, with a Florida home struck in March by a battery that fell from an International Space Station cargo mission.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

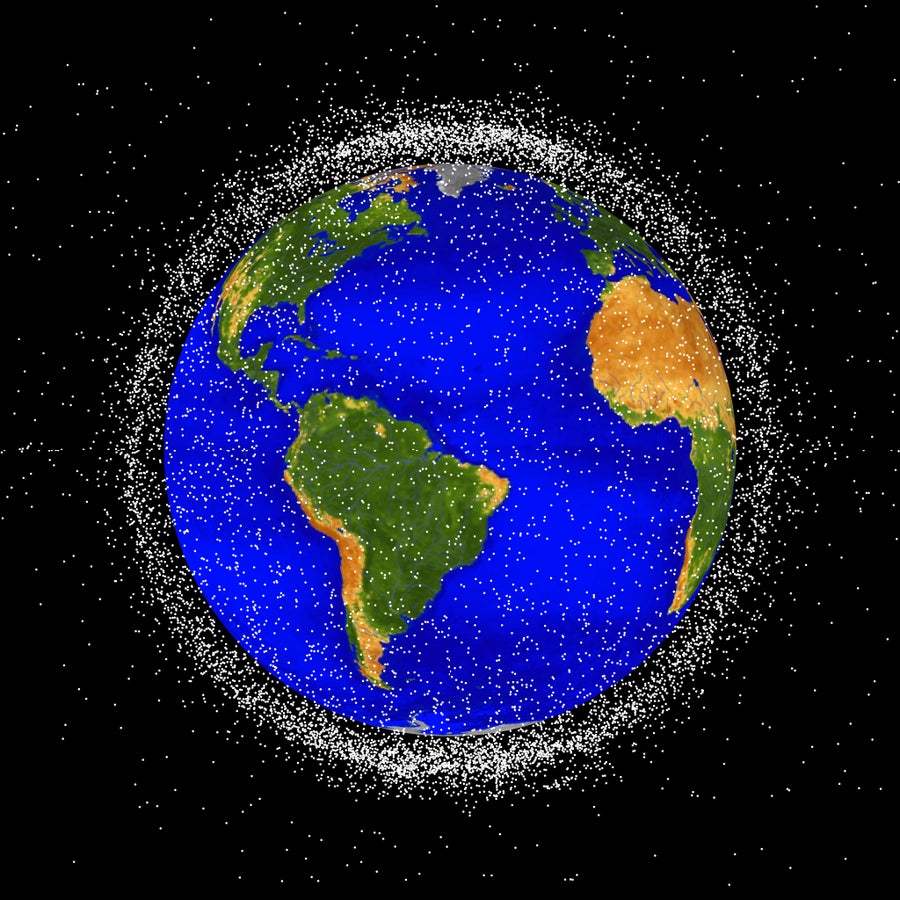

In space, debris comes from the frequent breakup of expended rocket bodies, explosion of satellites, dead satellites, collisions, paint flakes and even tools lost by astronauts. Around 85 percent of this debris resides within low-Earth orbit, which is below 2,000 kilometers in altitude. NASA estimates this orbit contains around 34,000 pieces of debris larger than 10 cm in diameter, 900,000 objects between 1 cm and 10 cm, and more than 128 million fragments between 1 mm and 1 cm. But let’s not be fooled by the size. Even small debris traveling at high velocities can trigger catastrophic collisions, with the added problem that fragments smaller than 10 cm are impossible to track with existing surveillance technology. An even more dangerous threat is self-propagation. Called the “Kessler syndrome,” this phenomenon occurs when collisions produce so much debris that Earth’s orbit becomes unusable for any human activity.

We must stop the growth of space debris, while realizing it is a demanding task. Neither national governments nor international organizations control property rights on orbit, apart from spacecraft ownership. Therefore, space activities are not subject to any centralized regulation or property rights scheme. In outer space “first come, first serve” instead applies. Like other global economic failures on Earth (such as fisheries in international waters, high seas sailing and climate change) that international cooperation has failed to solve or left only partly solved, overuse and depletion are direct consequences of such a “tragedy of the commons.”

In all these cases, including orbital debris, pollution exerts a cost on society where market prices do not capture the impact. Such “externalities” are market failures that, in most cases, require intervention from a government or other central authority. Simply put, rocket launch prices don’t reflect their real costs, which include clean-up expenses. We must reverse this situation before the cost becomes too high. Although human exploration and economic exploitation of outer space are relatively recent (the first human-made spacecraft, Sputnik, successfully launched in 1957), evident market failures and other economic, legal and political issues are arising at rocket speed as commercial, military and scientific activities in outer space expand. SpaceX is now developing a massive rocket that will launch 1.25-ton satellites like a Pez dispenser, adding to a fleet of 5,500 Starlink satellites already in space, part of a planned constellation of 42,000. That’s particularly alarming, because, according to a study of ours published last year in Ecological Economics, low-Earth orbit can only hold about 72,000 satellites without a real risk of a Kessler syndrome event, under current debris conditions.

LEO stands for low Earth orbit and is the region of space within 2,000 km of the Earth’s surface. It is the most concentrated area for orbital debris, represented with white dots and scaled to optimize visibility.

No surprise, spacefaring nations that are most dependent on satellites face the biggest risks of space debris. Instead of cooperating to mitigate space debris, however, they have failed to take decisive action. That’s despite the increasing probability of losing satellites, resulting in more resources that must be dedicated to debris surveillance tracking and collision-avoidance maneuvers that interrupt services and burn fuel. That, in turn, reduces the operational life of satellites, adding to their costs as the threat burgeons. Nonetheless, spacefaring companies have no incentive to minimize debris generation except for protecting their own spacecraft, which they do with shields.

We need both passive and active moves before space junk gets out of control. Space agencies and the United Nations have elaborated guidelines for debris mitigation. Some include changing the design of satellites with shields and reinforcing fuel systems to avoid breakups. Another recommends that all spacefarers provide spacecraft with maneuverability and add reserve fuel to de-orbit derelict spacecraft.

On the active measures side, developing debris-free recovery launch vehicles will greatly help to eliminate the primary source of debris. But there are still other sources, and given current orbiting derelict stock, active depolluting actions are also necessary. That’s because the life spans of orbital debris vary depending on altitude. Below 200 kilometers, it may only last a few days, whereas those at 1,000 km can last up to a thousand years. At 2,000 km, the debris can remain in orbit for up to 50,000 years without human intervention.

Cleaning space requires designing and implementing active debris removal (ADR) projects. ADR vehicles can be equipped with robotic arms, nets, collecting balloons and other tools. Earth-based lasers might also increase the atmospheric drag of debris, as another option. Policy makers must explore financing the cost of removal policies with instruments already in place for mitigating pollution on Earth. They should also develop guidelines and regulations to share the space junk removal cost among all spacefaring agents.

Finally, there is also a more alarming problem to pay attention to: the military’s use of space. Space pollution results not only from commercial and scientific activities, but also because of outer space’s growing strategic value for defense, security and warfare. Hard as it is to understand, Earth’s orbit has been polluted not only accidentally but also intentionally, as some countries have conducted antisatellite tests using missiles that destroyed their own satellites. The last one, performed by Russia in 2021, created a vast cloud of hundreds of thousands of fragments, dramatically increasing orbital debris at the most congested and polluted altitudes.

The militarization and weaponization of outer space contribute to orbital debris while acting as a roadblock to the de-pollution of space. Development of debris removal vehicles and devices is hindered by their dual-use status as antisatellite weapons, a significant obstacle to implementing international policies for eliminating orbital pollution. Any ADR technology could also be viewed as an offensive weapon, as it could remove enemy satellites from orbit. For the same reason, the militarization of outer space could threaten the development of new in-space industries for the servicing, refueling, upgrading, maintenance and repair of satellites. Humanity instead needs a clean, safe and regulated space environment to build a better world on Earth.

This is an opinion and analysis article, and the views expressed by the author or authors are not necessarily those of Scientific American.