How to Go the World’s Most significant Camera from a California Lab to an Andes Mountaintop

A multimillion-greenback electronic camera could revolutionize astronomy. But initially it wants to climb a mountain halfway all around the globe

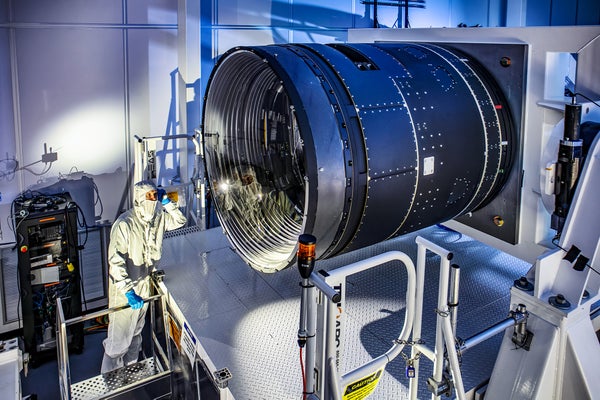

A employee shines a flashlight into the Vera C. Rubin Observatory’s digital camera.

J. Ramseyer Orrell/SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory/NOIRLab (CC BY 4.)

By late future 12 months, if all goes to prepare, the Vera C. Rubin Observatory will have started out its 10-calendar year survey of the photo voltaic process, Milky Way and galaxies past. Its big eye on the southern skies is a 3.2-gigapixel digicam with the dimensions and weight of a little car or truck. By mass and pixel resolution, it is the biggest electronic digital camera on Earth. It will scan the cosmos from atop a mountain identified as Cerro Pachón in northern Chile.

There is just a single hitch: the delicate, practically a few-metric-ton device is at this time some 10,000 kilometers absent in the hills previously mentioned San Francisco Bay, the place its builders have place it through closing exams. In the coming weeks the precisely engineered digicam will start out a tense intercontinental voyage in which it will be flown by cargo aircraft, hauled by truck and painstakingly escorted up twisty mountain streets.

The overwhelming logistics tumble to associates of an obscure but consequential engineering subfield committed to retaining multimillion-greenback astronomy components intact in transit. This is “a pretty apparent and seen instant when factors can go improper,” claims engineer Margaux Lopez of the Rubin Observatory and the SLAC Countrywide Accelerator Laboratory, who is in demand of the hard work.

On supporting science journalism

If you might be having fun with this posting, look at supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By getting a subscription you are encouraging to guarantee the foreseeable future of impactful tales about the discoveries and suggestions shaping our entire world nowadays.

The Rubin camera’s journey begins in a clean room in Silicon Valley, wherever SLAC will outfit the digital camera with a metal-and-wire-rope exoskeleton. “It’s a body sitting on springs on one more frame, in essence,” suggests SLAC and Rubin engineer Martin Nordby. This shield will retain the camera tucked within the confines of a typical delivery container and protect its delicate innards from vibrations. Then, around two times in May well, SLAC staff will drive the camera’s container and 49 crates of equipment to San Francisco International Airport, where by all the things will be packed aboard a chartered Boeing 747 cargo airplane for the 16-hour flight to the Arturo Merino Benítez Intercontinental Airport in Santiago, Chile.

The Rubin team is rather lucky: pieces of other telescopes in advancement, also certain for observatories below Chile’s extremely apparent skies, must shell out weeks traveling at sea. When the Fred Younger Submillimeter Telescope sends its five-story-tall support construction—too significant to healthy into a freight aircraft—from Germany to Chile, it will have to do so via break-bulk cargo ship by way of Antwerp, Belgium.

The Particularly Massive Telescope (ELT)’s big mirrors are having the ocean route from Europe to Chile, as well. “Historically…, we transported mostly all the things by plane, but with the new style of dimensions we’re chatting about with the ELT, planes both are not big enough or the expenses are ridiculously substantial,” says Hervé Kurlandczyk, an engineer for the European Southern Observatory, who will work on ELT and is not included with the Rubin task.

Physical destruction is always a danger, no issue the route or method of transportation. Astronomy, by structure, requires some of the most fragile components in the world. Anything from bumps in the highway to turbulence in the air can rattle sensitive electronics or jostle painstakingly positioned pieces out of alignment. Mirrors, which include Rubin’s items that arrived in Chile in 2019, might have to have refrigeration and humidity controls or risk harm to their coating.

Transit provides other attainable head aches that are common to any one seasoned in intercontinental transport. Negative weather conditions and other snafus can redirect or stall transports. Quite a few many years in the past miscommunication triggered the container ship carrying aspect of the Simons Observatory to sit at anchor for two weeks off Chile, leaving observatory employees scratching their head in port. Even observatories want to distinct customs, particularly when exiting the U.S. astronomical devices made in the U.S. may possibly, for instance, run into federal government export controls built to retain innovative optical technological know-how inside of the country’s borders.

All these anxieties suggest engineers check out “to command, as a great deal as doable, every single solitary step of the whole chain,” Kurlandczyk says. Whilst Santiago is on the other side of the equator from San Francisco, SLAC will go on to oversee the camera’s transit within Chile. The moment the 747 lands, its cargo will be loaded into a caravan of 9 vehicles—each similar to the curtain-side trucks employed to transportation beverages and outfitted with air-journey suspensions for supplemental security from vibrations. The caravan’s six-hour highway excursion to the foundation of Cerro Pachón will be a prelude to the most arduous element of the voyage: acquiring the camera from the base of the mountain to the observatory atop one particular of its peaks.

Rubin Observatory/NOIRLab/NSF/AURA/H. Stockebrand (CC BY 4.)

This past leg will be a 35-kilometer journey up a winding snake of grime roads and switchbacks. It will be slender and perilous, and the observatory at the prime won’t be capable to obtain far more than a single truck at a time, so the system will take a few times, with a few vans for every working day. And the truck carrying the digicam alone, escorted in front and guiding by observatory cars, will be in a position to journey no more quickly than 10 kilometers per hour. Lopez states the camera’s ascent will just take 5 hrs to make a trip that will take most other cargo about 90 minutes.

Lopez and her colleagues can get some convenience in the fact that they’ve presently practiced just about just about every move of the trip making use of dummies with the identical mass as the telescope areas. They’ve loaded these weights into trucks driven up and down the freeways of the San Francisco Peninsula and alongside Chilean roads they’ve even rehearsed the flight from California to Chile.

“Every time we cope with a thing, it is primarily the initially time it’s at any time been performed,” Lopez states. “We’ve put in a whole lot of effort and hard work to figure out techniques to exercise these sensitive procedures with something that is not as fragile just before we do it with, you know, $25-million optics.”

Much more than 5 many years of preparing have long gone into the camera’s six-day journey. “This has to operate. It has to be thriving. We can’t break anything at all alongside the way or lose just about anything or—pick your favourite failure method,” Lopez claims. “But we have a really good logistics prepare, and we’re prepared to go.”