Scott Schuyler knew it was going to be a tense evening in Newhalem, where a few dozen scientists, officials and residents had gathered at the community center to talk about living among apex predators. This remote village adjacent to North Cascades National Park is a tiny company town owned and operated by Seattle City Light—a utility that long ago built a succession of dams on the neighboring Skagit River to generate power for Washington State’s largest city.

Schuyler, an Upper Skagit Indian Tribe Elder and policy representative, had already spent years fighting the utility company for impeding salmon runs on his tribe’s ancestral land. He’d witnessed the dams imperil all five Pacific species of the fish found in the river; the tribe’s chum salmon fishery had disappeared entirely. That November night another spiritual relative of the Upper Skagit—one who’d been missing for a long time—was on his mind.

For millennia grizzly bears roamed this vast stretch of wilderness in north-central Washington. Fur trappers and hunters killed thousands of them during the 19th century, essentially eliminating them from the landscape. The last official observation of a grizzly in this ecosystem was in 1996. But in the fall of 2023 federal agencies had released a plan to reintroduce grizzly bears to the U.S. portion of the North Cascades Ecosystem—a mountainous region roughly the size of Vermont, located within a couple hours’ drive from coastal cities, including Seattle and Bellingham. It’s part of a broader recovery effort across the American West that was finally getting traction here after decades of bureaucratic starts and stops.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and National Park Service had presented three scenarios. Two of them would aim to create an initial group of 25 bears over a five- to 10-year span. These bears would arrive by helicopter and trucks from other regions in the U.S. and British Columbia, with the long-term goal of generating a population of 200 grizzlies in the North Cascades within 60 to 100 years. One course of action would treat them as a threatened species under the Endangered Species Act; another, which the agencies listed as their preferred alternative, would less conventionally designate them as a “nonessential experimental population” under a little-known rule in the act. This would allow authorities greater latitude to catch or kill bears to stop conflicts between the animals and humans. Crucially, it would also allow landowners in some areas to obtain a permit to kill a grizzly under specific circumstances. (A third “no action” alternative would involve no bear movement at all.)

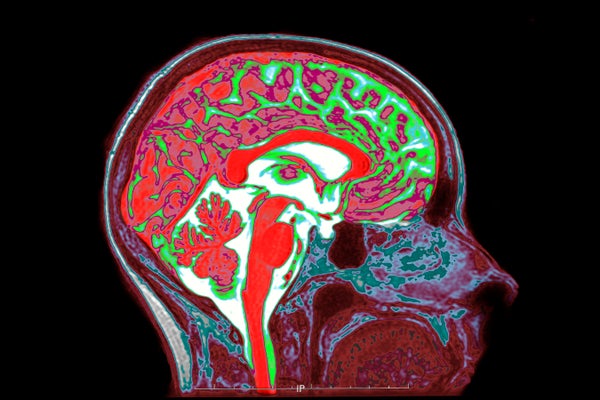

In Alaska’s Lake Clark region, a grizzly bear searches for salmon in a river. Grizzlies haven’t been spotted in Washington’s North Cascades since 1996.

In a handful of comment sessions held around the region and virtually, the public was now weighing in on how these various plans would affect the environment and the residents’ lives. At another meeting two days earlier in a valley east of the North Cascades, scores of ranchers and other locals had vehemently opposed any plans to reintroduce the bears. Backed by a local congressional representative, they saw such an action as a threat to their livestock and to the community at large. Some speakers blew past their two-minute limits; one man gripped a pitchfork with a cutout of a bear claw that read “NO.”

As Newhalem’s first speaker, Schuyler began in a conciliatory tone. “We respect everybody’s right to their opinions,” he said, before sharing that the history of his tribe had been intertwined with the history of the grizzly bear for 10,000 years. “I hope it’s not a surprise to folks,” he said, “that we’re going to support restoration.” Many speakers agreed, making comments along the lines of one from Brenda Cunningham, a retired biologist: “I’m willing to camp with care in these places because I feel we need to share the wilderness with all the species in the ecosystem,” she said. “The notion that we need to have completely safe experiences in the wildest areas of this incredible country seems very selfish to me.”

But fear of the grizzlies was palpable. Of the six designated recovery zones in the U.S., this one is closest to a major city—the Seattle metropolitan area is home to more than four million people. And the rural communities near the proposed release areas could, according to the plan, experience “adverse” effects such as “depredation of livestock or agriculture.” A local farm-bureau president said none of the organization’s members supported reintroduction. A campground owner explained that tourists already fret about encountering black bears and suggested that recreationalists might be dissuaded from visiting the North Cascades if they thought grizzlies were around.

As the months-long process played out, debate over human-bear conflict revealed a surprising range of views about what it means to belong to an ecosystem. It also invited a fundamental question: What, exactly, were the grizzlies supposed to bring back?

For thousands of years people who lived in the North Cascades coexisted with grizzly bears. They revered the massive creatures for their hunting skill; according to Upper Skagit lore, the bears could imbue humans with their hunting prowess. The Stetattle Valley, which is part of Upper Skagit ancestral land, draws its name from the Lushootseed word for “grizzly bear.”

In the 19th century Upper Skagit bands resisted white settlers’ attempts to drive them onto distant reservations. But their four-legged neighbors gradually disappeared as grizzlies became targets for hunters and fur trappers. Between 1820 and 1860 Hudson’s Bay Company reported that nearly 4,000 grizzly hides were shipped from trading posts in the area.

Some people fear a grizzly bear reintroduction in Washington could harm salmon populations—but dams are a much bigger threat to the fish.

Throughout the central and western U.S., hunting and habitat loss caused by new settlements destroyed a population that once stretched from Mexico to the Arctic. Even as the grizzly bear came to symbolize the power of the wilderness, that power, for some, still manifested as a risk to be “managed,” and Ursus arctos horribilis largely vanished from the landscape. In 1975 grizzlies were listed as threatened in the lower 48 states under the Endangered Species Act. By then, an estimated population of 50,000 bears in the contiguous U.S. prior to 1800 had plummeted to fewer than 1,000.

In the early 1980s a government effort was started to recover the animals in habitat zones across Montana, Idaho, Wyoming and Washington. That initiative eventually included the North Cascades Ecosystem. In the Cabinet-Yaak Ecosystem, which runs across northwestern Montana and northern Idaho, the federal agencies started translocating grizzlies from Canada, where populations were healthy. For the first time in the U.S., people were moving grizzlies for a recovery effort.

Wayne Kasworm, a wildlife biologist with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s Grizzly Bear Recovery Program, can still remember the skepticism from locals when the feds explained they were going to capture bears from the British Columbia backcountry and release them around the Cabinet Mountains, where there were, at most, 15 grizzlies at the time. In part to pacify those pushing back, the program began as an experiment: From 1990 to 1994 they’d capture four young females using foot snares, culvert traps and dart guns and truck them across the border and set them free in remote areas. Then they would see if the bears produced any cubs.

It would take a while to render a verdict. Among North American mammals, only musk oxen reproduce less than grizzlies over the course of a lifetime. Finally, in the early 2000s, DNA analyses from hair-snagging snares helped to prove that one of the bears had produced a number of offspring. Land managers are now seeing the third generation of descendants from that bear, whom they named Irene. Today the ecosystem has probably somewhere between 60 and 65 grizzlies after introducing 26 translocated bears. “Overall, it’s gone better than expected,” Kasworm says of the recovery program. The government plans to add a bear or two to the Cabinet-Yaak every year for the foreseeable future.

The Cabinet-Yaak recovery has served, in many respects, as a template for the North Cascades, Kasworm says. One major difference between them, however, is that the Cabinet-Yaak augmentation region had a small grizzly population when the program began. “Starting from either no bears or very few bears,” Kasworm says, “is possibly a lot tougher than starting with some bears to get a population going.”

To establish an initial population of 25 grizzlies in the North Cascades, the reintroduction plan calls for the capture of three to seven bears a year for up to a decade from the wilds of British Columbia; the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem; and the Northern Continental Divide Ecosystem, which includes Glacier National Park, in northwest Montana. Crews would deploy culvert traps or, where feasible, shoot tranquilizers from helicopters to capture the bears. (In some instances, they may also use snares.)

If a trapped bear met the criteria for being a founder—between two and five years old, with no cubs or history of conflict with humans—they’d transport it by air and truck to remote public land in the North Cascades, tracking the animal via a GPS collar. Other trapped bears would be let go.

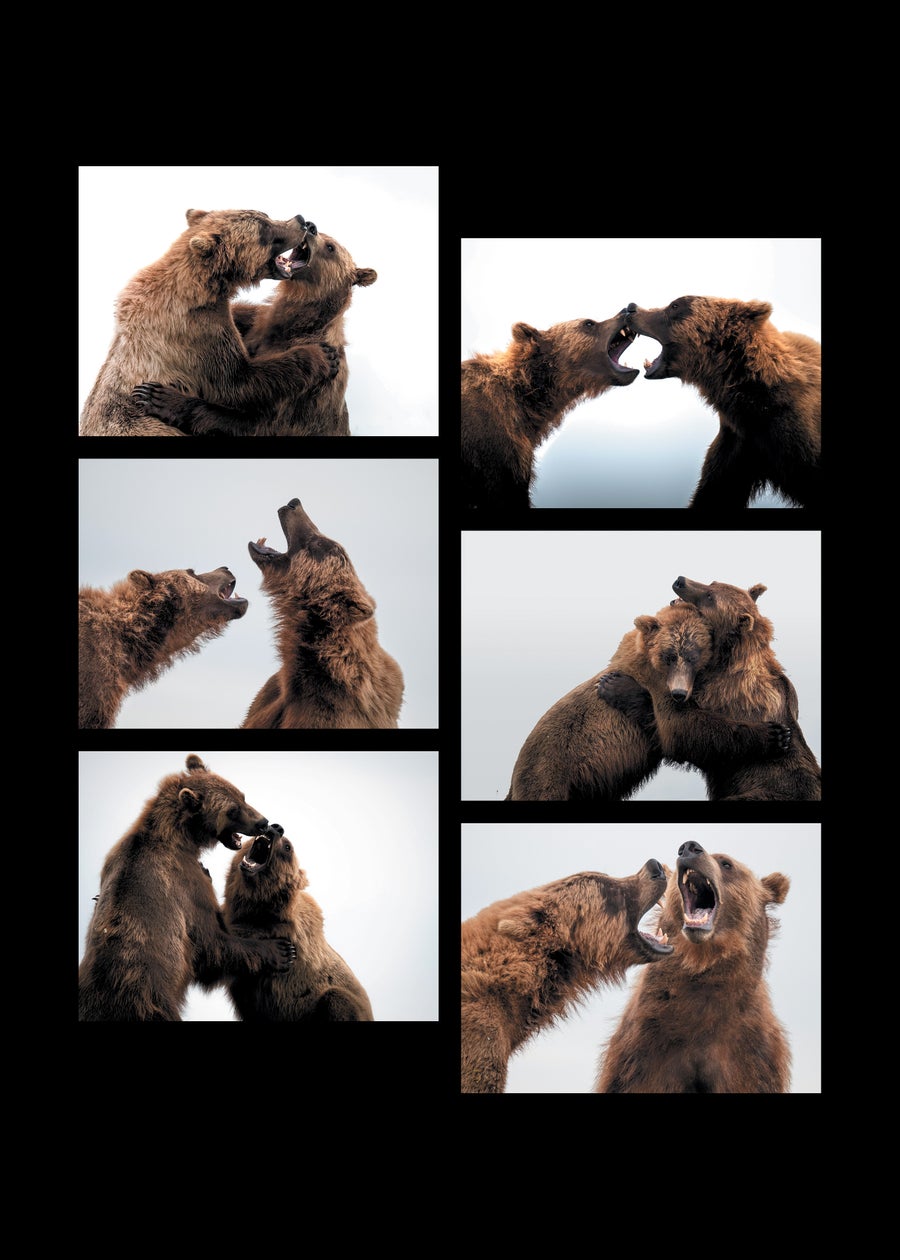

A mature female grizzly stands tall to investigate an approaching bear. This behavior is a sign of curiosity, but people sometimes misinterpret it as aggression.

Mortalities during grizzly captures and translocations are rare; between 1980 and 2009 less than 3 percent of known grizzly deaths in the lower 48 states could be traced to scientific research or conservation, according to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. The bigger uncertainty is what will happen once they’ve arrived in the North Cascades. A study of 110 grizzly bear translocations in Alberta, Canada, found that these efforts failed 70 percent of the time. In the failure cases, bears were killed both legally and illegally; engaged in repeated conflicts; or wandered back toward their original capture area.

Dana Johnson, policy director with the national nonprofit Wilderness Watch, worries about both the mechanics of translocation—an estimated 144 helicopter landings to release, handle and recollar the grizzlies could disturb surrounding mammals and birds—and the potential disorientation of the founders themselves. “They have established home ranges. They have established social structures. They know where their favorite food sources are,” says Johnson, who clarified she does support reintroduction. “These are animals that have communities.”

Kasworm, acknowledging the challenges of translocation, estimates it would require moving about 36 bears to build the initial population of 25 in the North Cascades. “Not all of those animals that you move are going to stay where you intended them to be,” he says. “And not all of them are going to live.” In the Cabinet-Yaak Ecosystem, bear losses have been caused predominantly by humans. In 2009 an elk hunter who said he was acting out of self-defense killed a bear that turned out to be Irene.

The night after Schuyler advocated for the reintroduction program in Newhalem, Shawn Yanity and Kevin Lenon made their way to the front of a packed auditorium inside a high school in Darrington—a logging town 35 miles away. These two tribal leaders had shown up to similarly weigh in on the environmental impact statement of the federal plans, but they had a significantly different message.

“The bear is definitely a big part of our culture here in Indian country, as all the animals are,” said Yanity, a former chair of the Stillaguamish Tribe of Indians. “But as time has moved on, things have changed.” Specifically, he worried the bears would endanger some of their food and economic resources. “We face declining salmon,” he said. (Research in the government’s plan shows that the bears aren’t expected to endanger the fish population.) Lenon, a member of the Sauk-Suiattle Indian Tribal Council, echoed Yanity’s concern about the salmon and said his people would hunt the bears if they were reintroduced. He then stated a belief seemingly shared by many in the room: “These people,” he said, referring to the federal officials in attendance, “don’t give two cents about any of your human lives. Because I’ve told them already, you’re going get people killed in the North Cascades.”

One by one, people raised concerns about their community’s safety. Some cited what has happened in Montana, where conservation efforts raised the grizzly population in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem from 136 bears in 1975 to 965 bears in 2022. The area in and around Glacier National Park now counts the largest grizzly population in the lower 48 states. The bears have extended their range between these ecosystems, migrating into plains and valleys and encountering more humans along the way. Montana, Idaho and Wyoming have all recently petitioned the federal government to delist the bears from the Endangered Species Act because of the rising number of bears.

Data on conflicts haven’t quite caught up to the bears’ increasing sprawl. In Yellowstone National Park, though, the National Park Service reports just 44 visitors injured by grizzlies since 1979, or one for every 2.7 million visits. Grizzlies have killed seven visitors since the park was established in 1872—two more than have been struck and killed by lightning during that time. Generally speaking, U.S. Forest Service regional wildlife ecologist Andrea Lyons says, “you’re more likely to die driving to the trailhead than you are from a grizzly bear encounter.”

The North Cascades National Park Complex—which drew nearly one million visitors in 2023—isn’t Yellowstone busy (4.5 million visitors in 2023) or as popular as Mount Rainier or the Olympic Peninsula, the sites of Washington’s two other national parks. Visitors can find true solitude in the alpine expanses where the peaks’ snowcaps trickle down to aquamarine lakes and rivers. The region is also the largest of the grizzly bear recovery zones, covering 9,800 square miles. Modeling efforts have found the landscape could easily support about 280 bears. In other words: there’s plenty of room for them.

Still, officials don’t deny there would be conflicts in the North Cascades. Studies have found that attractants such as orchards, beehives, and cattle and sheep calving areas are associated with encounters between humans and grizzlies. Rates of reported conflicts tend to be highest during grizzlies’ extremely hungry phase, called hyperphagia, that occurs before hibernation. As part of the reintroduction plan, agencies would provide more education about bear spray and storage of human food, pet food and garbage.

“Grizzlies were lost because people killed them. It wasn’t some rogue disease or habitat loss.”

—Jason Ransom National Park Service

In Washington, the public might have more options for handling encounters. Traditionally, as a threatened species under the Endangered Species Act, bears could be captured or killed only during defense of life, research or conflict situations by federal, state or tribal authorities. Because grizzly bears have disappeared entirely from the North Cascades—unlike in other recovery zones—officials could use the “nonessential experimental population” designation to allow for additional “take” activities for limiting conflicts. According to the environmental impact statement, this would include permits for landowners to kill a grizzly if it is presenting an ongoing threat to humans, animals or property and if “it is not reasonably possible” to quell the bear via nonlethal means.

Some reintroduction advocates have concerns about allowing greater liberties for taking grizzlies, and they worry that a broader definition of who is allowed to kill a bear, and under what circumstances, might lead to unnecessary bear deaths. Others, such as Jason Ransom, a senior wildlife biologist with the National Park Service, view it as a necessary step to push through a program that has fallen victim to changing administrations and volatile politics for many years. As a scientist who’s long worked on bear recovery, Ransom says it’s not strictly a matter of biology or ecology that underlies his support.

Last September, Ransom trekked to Fisher Creek Basin, the site of the last known killing of a grizzly bear in the North Cascades. There’s something about being in a wild ecosystem “that resonates differently with our well-being as a culture,” he says. “When you have big pieces missing, [our well-being] is degraded.” The grizzlies, he explains, “were lost because people killed them. It wasn’t some rogue disease. It wasn’t habitat loss.”

The last verified sighting at North Cascades National Park came in 1991. (Hikers have filed many false reports of grizzlies since then. Most sightings are probably of black bears, which are comparable in size to interior grizzlies and can have similar blonde, brown and cinnamon coats. But they lack the grizzly’s signature shoulder hump.) Unlike other parts of the country where grizzly bears vanished with habitat loss, however, officials have managed the North Cascades as a grizzly bear recovery area since 1997. Thousands of plant and fungi species could serve as potential food sources; despite their carnivorous reputation, the bears are omnivores who largely dine on vegetation. Huckleberries, a grizzly favorite, abound in the region.

With this diet come ecological benefits. Bear scat would disperse seeds across the landscape. Their massive claws would turn up and aerate soil when they dig for roots and rodents. If humans leave them alone—and they very much want to be left alone—they would become a fixture of the landscape amid a biodiversity crisis. A study published in Biological Conservation projects that warmer, wetter weather would create more vegetation for grizzlies to eat. Other species may die off, but grizzlies “are going to be winners in the climate change game,” says Ransom, a co-author of the study.

Ransom calls grizzlies a keystone species, in the sense that they have an outsize effect on their natural environments relative to their population size—not in the sense, as some use the term, that an ecosystem will fall apart without them. The North Cascades region has shown it can adapt, and “I hope and expect that the ecosystem will remember them,” he says.

On March 21, after reviewing nearly 13,000 public comments, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the National Park Service took a big step toward approval: They issued a final environmental impact statement that reiterated their preference to reintroduce grizzly bears to the North Cascades as a nonessential experimental population. An official “record of decision” was published in April, though there is not yet a set timeline for when bear translocations may begin. (A similar process is now underway for the Bitterroot Ecosystem, a designated grizzly recovery zone in Idaho and Montana; a decision is expected by 2026.)

Two subadult grizzly bears wrestle in Alaska’s Katmai region.

Regardless of what moves the U.S. government makes, grizzlies will likely be arriving in the North Cascades. Since the passage of a tribal council resolution in 2014, the Okanagan Nation Alliance—an organization that supports a coalition of First Nations—has been working to recover grizzly bears in Canada. This year the group is planning to augment a population of about six bears on the Canadian side of the North Cascades, according to biologist Cailyn Glasser, a resource manager for the Okanagan Nation Alliance.

The bears “don’t care about borders,” Glasser says. As the region’s grizzly population grows, she thinks it’s only a matter of time before the bears venture south to the U.S. (Glasser says she’s in regular contact with U.S. officials to coordinate their efforts.) The bears are “going to go back and forth, and the reality is that the best habitat in that ecosystem is right along the border.”

To Schuyler, the Upper Skagit Indian Tribe Elder, grizzlies and people can always coexist: “It’s just never a choice between us or them.” Schuyler traveled to Washington, D.C., in March to impart this belief to representatives of a government that historically tried to force his people from their land. The parallel wasn’t lost on him. “We’re advocating for ourselves,” he says, “not just the grizzly bear.”