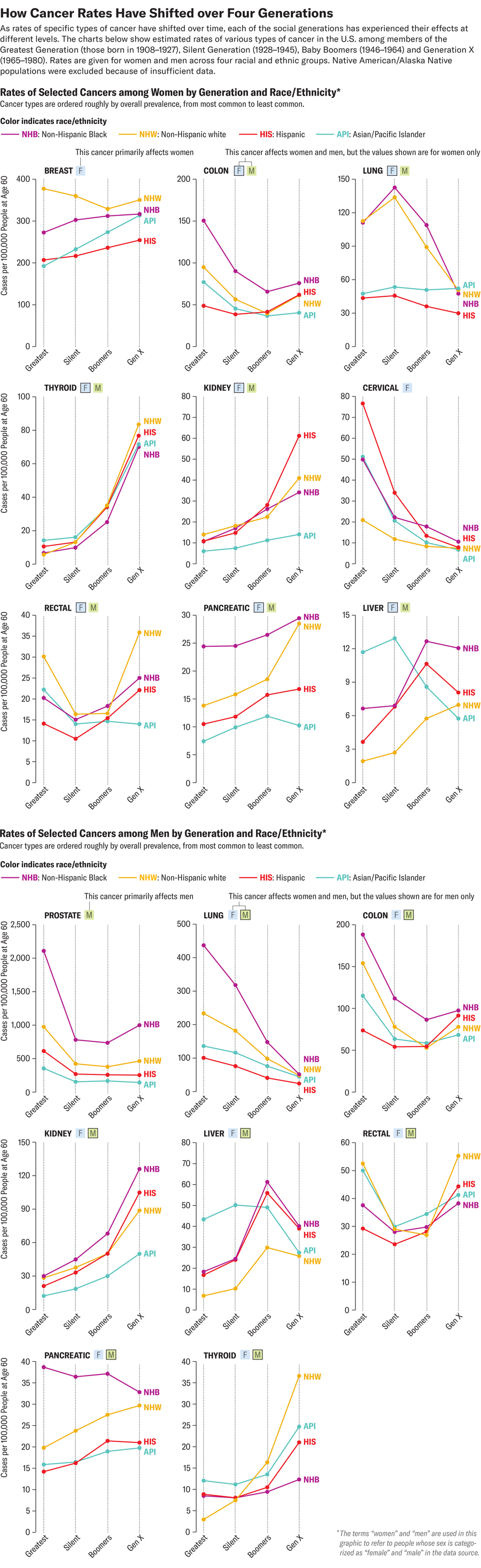

A major new study projects that members of Generation X—people born between 1965 and 1980—have a higher rate of developing cancer than their parents and grandparents. And researchers are struggling to identify the reasons why cases are rising. Could it be related to changing diets or exercise habits? Are cancers themselves evolving to be wilier and more pernicious? The new research offers some possible clues.

The model study, published in JAMA Network Open, sifted through cancer surveillance data collected between 1992 and 2018 on 3.8 million people in the U.S. Researchers looked for patterns in invasive cancer cases—those that have spread beyond the original site—within and among Generation X, Baby Boomers (people born in 1946–1964), the Silent Generation (1928–1945) and the Greatest Generation (1908–1927). The findings suggest that medical advances against some cancers—gained by better screening, prevention and treatment—have been overtaken by startling increases in other cancers, including colon, rectal, thyroid, ovarian and prostate cancers. This troubling trend has researchers baffled and scrambling for answers.

“It’s really something that has been observed in multiple studies, and now I think it really is an undeniable fact that we’re seeing cancer rise in younger people,” says Andrew Chan, a gastroenterologist at Massachusetts General Hospital and a professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, who was not involved in the new research. “The study really reinforced what we already know but also provided us some additional insights into the trends within particular cancer sites and more detail on the rates of increase within individual groups.”

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Social generations, also called “birth cohorts,” are one useful way of grouping people, explains Philip Rosenberg, a co-author of the study and a principal investigator at the National Cancer Institute (NCI). Tracking cancer rates this way can help researchers line up trends over time with certain parallel events, such as a new risk factor or carcinogenic exposure, or population-wide lifestyle or policy changes. This could provide insight into why certain cancers are developing at higher rates among different age groups—and, hopefully, offer ideas for prevention tactics. “We can finally kind of look at these patterns with a higher resolution that gets at different aspects of the story,” Rosenberg says. “One of the things we were able to do that was really novel was to sort of untangle that under-50 group and really assign the trends to birth cohorts.”

Previous studies have reported that people younger than age 50 are experiencing higher rates of certain types of cancers, particularly those of the digestive system. The rate of colorectal cancer, for example, has been steadily increasing in people younger than age 50, despite incidence rates declining overall in the U.S. The new study showed similar growing trends among Generation X, but “the surprise for me was that it wasn’t just colon and rectum cancers,” Rosenberg says. “It was the number of cancers that was a big surprise.”

Rosenberg and his co-author, NCI scientist Adalberto Miranda-Filho, predict in the new study that members of Generation X will experience increases in the rates of several cancers: those of the thyroid, kidney, rectum and colon. Additionally, women will experience higher rates of pancreatic, ovarian and endometrial cancers, and men will see increases in prostate cancers and leukemia. Generation X men are forecasted to have lower rates of liver and gallbladder cancers, while women are expected to see decreases in cervical cancer. All members of Generation X will also see declining lung cancer rates compared with those of previous generations.

Some of these trends have clearer explanations than others. For instance, improvements against cervical cancer can be linked to more effective screening, while lower lung cancer rates are attributed to significant reductions in tobacco use since the 1960s. “Smoking was a huge driver of not only lung cancer but many [other] cancers,” Rosenberg says. Cancer-detection measures, such as screenings and genetic profiling, have improved and become more widely available—but many researchers insist this isn’t pushing the new overall rates higher. “People are being diagnosed not because [cancers are] being picked up through better diagnostics but because they’re becoming, unfortunately, clinically and symptomatically apparent, and that is something that is not a feature of improved diagnostics,” Chan says. In other words, more cancers are being detected at advanced, invasive stages. “The pace and the magnitude of how much the incidence has risen couldn’t be explained by simply earlier detection.”

Figuring out what is driving rates up has been a more difficult question to answer. Several research groups, including the American Cancer Society and National Cancer Institute, point to diet, exercise and obesity as well-established risk factors that could partly explain the rising rates. These factors are “undeniable,” says Chan, who co-leads an international collaborative group called PROSPECT, which investigates early-onset cancer. And, he adds, “there’s clearly other factors that are driving this rise that have yet to be identified.”

In the case of early-onset colorectal cancer, gastroenterologists including Chan and Kimmie Ng, director of the Young-Onset Colorectal Cancer Center at Dana-Farber Brigham Cancer Center, have been treating more people who do not have any family history of cancer, hereditary conditions, or underlying health issues or lifestyle choices that would raise their risk. “Many of them are not obese. They live very healthy and active lifestyles and they eat healthily, yet they are still being diagnosed with very advanced stages of colon and rectal cancer,” Ng says. “And we are now also starting to see an uptick in very young people coming in with pancreatic cancer, bile duct cancer, appendix cancer—all of these different [gastrointestinal] cancers.”

Researchers are investigating other leads. Changes in food preparation, such as an increase in processed foods and meals, might be a factor—and so might environmental or chemical exposures, such as those from pollution and plastics, says Otis Brawley, a professor of oncology at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. Brawley also speculates that changes in the gut microbiome, partly from overuse of antibiotics, might influence colon, rectal and other gastrointestinal cancers. “The bacteria that inhabit people’s colons are different today than they were 60, 70 years ago,” Brawley says. “We know that the stool microbiome is related to things like ulcerative colitis and inflammation of the bowel—and we know that those two things are linked to colon cancer.” He notes, however, that research has not definitively linked the microbiome to colon cancer.

Ng and her colleagues at Dana-Farber are also working on identifying mutations and genetic modifications in younger people who develop colorectal cancer; the researchers want to see if the disease itself is biologically different in younger age groups. “Perhaps [the cancers] are a little more aggressive,” she says. “Maybe it could explain why perhaps many more of them are being diagnosed at stage three or four.”

Chan, Ng and Brawley all agree that it’s likely not just one or two factors at play but rather a convergence of new variables. The timing and duration over which a person faces these risks and exposures will also be important to understand; Chan says more research is needed on lifestyle and environmental risks as early as childhood and even during fetal development. “Carcinogenesis doesn’t happen overnight,” Brawley says. “It’s usually a process over decades.”

Age is still a leading determinant of cancer risk. Data are currently too limited to predict cancer rates for Millennials and Generation Z members, Rosenberg says, but the outlook won’t be promising if trends continue on their current trajectory. He adds that there’s still time for this to change—even for members of Generation X, who are the next group to reach their most cancer-prone years. “There’s no reason why the cancer rate has to stay on those trajectories in the next year, three years, five years down the road,” he says. Rosenberg hopes the recent study can help motivate and inform cancer prevention and research.

“It’s very clear to us that cancer is evolving from a disease which has traditionally been considered a disease of aging to one which affects, really, all age groups,” Chan says. “We need to develop more precision prevention approaches where we start to understand better who’s at risk in the general population and to start to target our efforts more directly to those people to make more headway.”