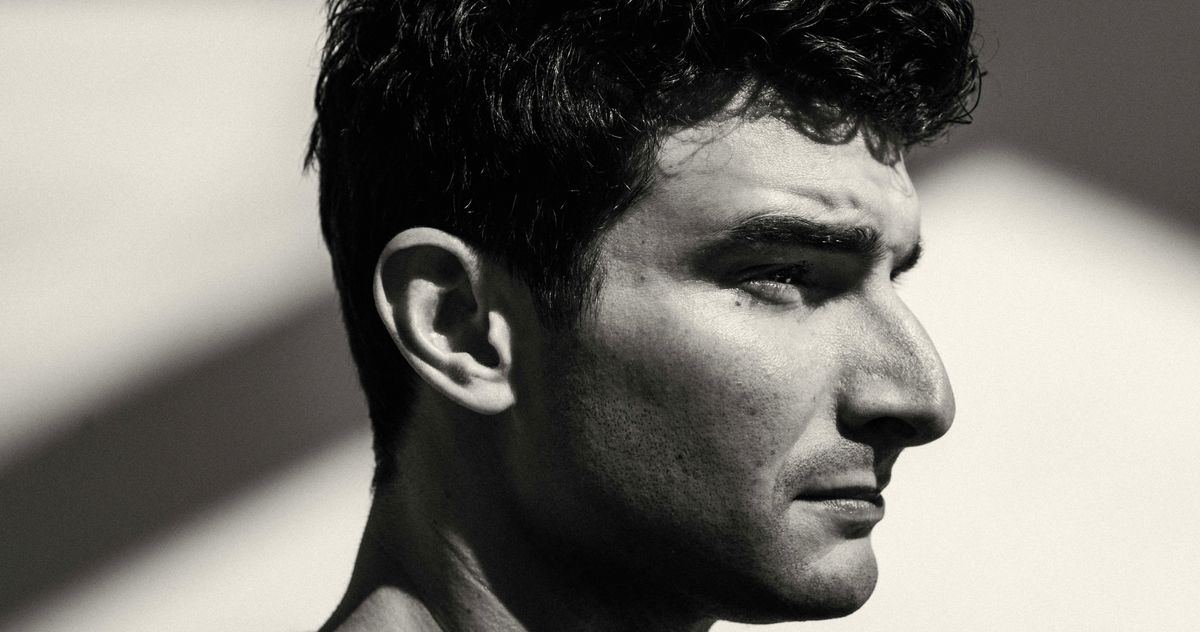

Photo: Christopher Anderson for New York Magazine

The writer Justin Kuritzkes became obsessed with pro tennis after watching Naomi Osaka beat Serena Williams at the 2018 U.S. Open in an infamous match fraught with argument. As Williams pleaded her case to the umpire, Kuritzkes realized how cinematic the situation could be: how alone each player was, yet how linked to each other. He started watching tennis all the time, and when he ran out of big matches, he found smaller ones like the Challenger tournaments — low-budget events that could help someone qualify for the highest level of competition. Some of the players there may be among the top 300 in the world, but they’re fighting for prize money that won’t even cover their expenses. Kuritzkes knew the feeling. At the time, he was a well-regarded playwright who struggled to get anything produced. “Although the stands at a Challenger are mostly empty, the players’ emotions are just as if they were at the U.S. Open because they’re fighting for their lives. It’s the humiliation of being a gladiator and nobody’s even there to watch you die,” he says. “I connected with that deeply as a theater person. If you asked me if I know the 271st most successful theater actor in America, I probably do. And I guarantee you they’re broke.”

In 2021, he decided to channel his tennis fixation into a screenplay — and now that screenplay is Challengers, a Zendaya-led production full of enough unsatisfied desire and close-ups of sweaty, beautiful young men to confirm that Luca Guadagnino directed it. The film follows three tennis players who have spent their entire adult lives entangled in one another’s careers and beds: Zendaya plays Tashi Donaldson, a former prodigy who should have gone pro but couldn’t. Mike Faist is her husband, Art, a six-time Grand Slam winner whom Tashi both coaches and disdains. And then there’s Patrick Zweig (Josh O’Connor), an all-id ex-friend and doubles partner to Art and ex-boyfriend to Tashi. When Patrick reencounters the couple at a Challenger in suburban New York, it throws all three of them into racket-smashing, early-onset midlife crisis.

Challengers is Zendaya’s first big-screen leading role, and she plays Tashi full of withholding and coiled, frustrated ambition; her idea of a pep talk before a match is telling her husband to “decimate that little bitch.” This is also Kuritzkes’s first screenplay. Now 33, he spent his 20s writing comic and disturbing plays that were supported by prestigious residencies and fellowships but rarely produced for the stage. Hollywood has been a lot faster to welcome him: After Challengers, he’s got another film with Guadagnino, an adaptation of the William S. Burroughs book Queer. Next, he’s adapting Don Winslow’s mob novel City on Fire with Austin Butler set to star. This would all seem more unprecedented if his wife hadn’t just done something similar: Kuritzkes is married to Celine Song, the former playwright whose own debut film, Past Lives, was nominated for two Oscars.

Even if most of the people who saw Past Lives didn’t know Kuritzkes’s name, Song’s press tour gave him a kind of secondhand, not-quite-accurate fame: The film is about a New York playwright who reengages with a childhood crush from South Korea and begins to question her marriage to her white husband. In interviews, Song talked at length about how her film was inspired by her own life. Now Kuritzkes has written a ménage à trois of his own. Like Past Lives, it hinges on a young woman who is forced to confront the romantic road not taken. Unlike Song, he’s not willing to discuss that theme. “Challengers is an intensely personal film to me — in ways that I’m not interested in talking about,” he says.

He dismisses the films’ similarities. “Love triangles are one of the most basic plots in cinema,” he says. “Even in a relationship between two people, there’s always a sort of imagined third presence.” I ask what that third presence might be. “Well, for a lot of people, it’s, like, Jesus,” he jokes. “Or it’s their conception of themselves, or their parents, or their friends. But in a love triangle, that third presence is not imagined.” Either way, he says, the parallels between his life and Past Lives or Challengers don’t matter: “Once it gets transformed into a work of art, the connection between that and the real thing is irrelevant. That’s just fuel that you’re using to propel a vehicle.”

Justin Kuritzkes on the set of Challengers.

Photo: Niko Tavernise/Niko Tavernise

Kuritzkes and I meet at the Fort Greene Park tennis courts in early April, settling down on a cold bench to watch the amateurs hit. To the left, four middle-aged white men play competent doubles. To the right, two young people struggle just to get the ball over the net. Suddenly, a horde of 14-year-olds stream onto the courts, running and yelling as they gather for what’s either an after-school tennis camp or an ad hoc hazing. When Kuritzkes was around that age, he had already quit his tennis lessons. “I could tell exactly how bad I was. I would have moments where it clicked and then wouldn’t be able to replicate it. That drove me crazy because I was like, Well, why can’t I just do that every time?” he says. “I decided I was as good as I was ever going to get and it wasn’t good enough. So I was done.”

Kuritzkes grew up in L.A., the son of a real-estate-lawyer mother and gastroenterologist father, and went to the prep school Harvard-Westlake, where he graduated one year behind Lily Collins and three years ahead of Ben Platt and Beanie Feldstein. The school had a student playwriting festival, and Kuritzkes became a regular participant, writing 10-to-15-minute plays. “The immediacy of theater was intoxicating,” he says. “You can just write something, get two chairs, and have actors do it and the audience will suspend their disbelief.” When he went off to Brown, “I already knew I was a playwright,” he says. In between working on his thesis, he started making character-study videos on his laptop, warping his face using the built-in effects of Photo Booth. In his most-watched video, “Potion Seller,” he plays a knight who keeps begging a merchant for potions.

He met Song the summer after he graduated, in 2012, during a fellowship in Montauk. Song fictionalized this first encounter in Past Lives in a woozy scene where protagonist Nora (Greta Lee) flirts with future husband Arthur (John Magaro) under the fairy lights at a dreamlike residency. Nora departs on a long definition of the Korean concept of in-yun — “It means providence, or fate” — before circling back to say it’s just “something Koreans say to seduce someone.”

Song has said they connected over their work, so I ask Kuritzkes, half-joking, how long it took before he showed her his YouTube videos. He stiffens. “I’m so thrilled and happy to talk about Celine in virtually every context, but I would never want to speak for her in the context of an interview,” he says. Too much in-yun has been spilled already. I point out that Song has spoken freely about their lives together. “I wouldn’t want anybody to confuse the character and me because it erases the work that she and her actor did, or it pollutes it,” he says. I ask if he thinks people do confuse him with the character. “I don’t know,” he replies, looking me straight in the eye. “Do you?”

In Past Lives, the husband is a gentle presence who recedes into the background. In real life, Kuritzkes comes off as preternaturally self-assured. “He has had that from a very young age,” says theater director Danya Taymor. “It’s not arrogance. He just believes in himself.” Shortly after Kuritzkes and Song started dating, “Potion Seller” went so viral that The New Yorker eventually published a parody of it; the video now has over 11 million views. The couple married in 2016, the same year Kuritzkes’s play The Sensuality Party — his thesis from Brown, a series of interlocking monologues from college kids who have an orgy that turns nonconsensual — was produced Off Broadway with Taymor directing. When Kuritzkes and another friend, the director Knud Adams, wanted to stage Kuritzkes’s play Asshole, they built the set themselves and rehearsed in their respective apartments. The play is about a doctor who oversees the force-feeding of prisoners at a government black site and is obsessed with his own asshole. Kuritzkes had written it in 2014 after reading about the force-feeding of Guantánamo prisoners on hunger strike. “The fact that everybody could go about our normal lives after hearing about it really freaked me out,” he says. “I started to think, Well, what would really repulse somebody? It would be a guy playing with his own asshole and smelling his own shit.” The production, at the Brooklyn theater Jack, was a surprise hit. As Adams remembers, “We sold out all our shows. But then it’s not hard to sell out Jack — there are 40 seats.”

Writing Challengers was an exercise in following desire. Deep in the grips of tennis mania, Kuritzkes had begun to wonder what could make watching the game even more interesting. “If I knew exactly what was at stake on an emotional level beyond the court for the people playing and the people watching, that would be just eating a plate of chocolate truffles to me.” His agent sent the script to the producers, Amy Pascal and Rachel O’Connor, who got it to Zendaya, who loved it. The actress wanted both to star and to co-produce. “One of the things I remember saying to Zendaya when we first met was that the cultural space that Zendaya occupies in the world is the space that the character Tashi was supposed to occupy — that was the life she was supposed to have,” says Kuritzkes. “I think she really connected with that ambition and that pain.” The producers and Zendaya who got Guadagnino onboard.

With Challengers, Kuritzkes became part of a machine: He was working with Guadagnino and the film’s tennis consultant, the coach and commentator Brad Gilbert, on the many gameplay scenes, which were choreographed like fights. Each one had to be shot with both body doubles and the actors, and only Faist came in with tennis experience. “During breaks, we would sometimes pick up racquets and play. I have really funny videos on my phone of Luca,” says Kuritzkes, smiling. “It was so adorable. He just couldn’t hit the ball to save his life.”

Kuritzkes says that he always imagined a charge between Art and Patrick — “There is eroticism present in every intimate friendship, especially one between two guys who have spent their lives in locker rooms and dorm rooms and on the court together” — and that Guadagnino’s interpretation pushed it further. Mostly, though, the boys are each other’s foils, with Patrick always willing to play the heel. In Guadagnino’s hands, this inevitably bends erotic. When the two first become infatuated with Tashi, Art says earnestly that she’s “a remarkable young woman.” Patrick replies, “I know. She’s a pillar of the community.” He lowers to a whisper: “I’d let her fuck me with a racquet.” Kuritzkes says that although none of the characters is based on a real player, it was important for Tashi to be a Black woman. “The story of American tennis is Black women for the past however many decades,” he says. “I also knew that I didn’t want to not specify the races of the characters. That always feels to me like you’re avoiding something. Her being a Black woman informs a lot about how she navigates her situation and how she navigates her relationship with these guys.” The Zendaya line making the rounds in the film’s trailer — “I’m taking such good care of my little white boys” — sounds affectionate only on paper.

When Kuritzkes was a kid, he felt bad that so many of the films he loved, like Jules et Jim and Y Tu Mamá También, were about love triangles; he felt guilty getting so much pleasure from watching a scenario in which someone was being wronged, rejected, or hurt. Now he believes movies are exactly the right place for it. “Part of the joy of watching it is thinking, At least my life isn’t as messed up as that, or, My life is as messed up as that, and thank God I’m not alone,” he says. “What’s good for art is the opposite of what’s good for life.”