The streaming juggernaut fronts as wallpaper TV, but its uncanny fiction is anything but easygoing.

Photo: Keri Anderson/Prime Video

It was a chilly April afternoon when my mother came to visit Chicago from south Florida and I had to figure out a wallpaper-television option that suited her specific appetites. My Black Creole mother, resolutely and proudly southern, may not be the kind of person most critics would look to as a barometer for the taste of the average American, but she’s always been a good gut check for me when considering the preferences of people for whom cinephilia isn’t the goal, just entertainment. My mother’s taste is best described as normcore Americana. I thought through true crime and romantic dramas that would speak to her before I started mulling over the streaming juggernaut Reacher, which wrapped its second season earlier in the year. I had been hearing a lot about the series from writers and friends on social media — about its righteous fun and how hot they find the lead.

Wallpaper TV is marked by an easygoing approachability and a low lift for concentration. These are series propelled by vibes that you can groove to as a viewer but whose characterization, narrative, and visual dimensions hew toward simplicity, if not banality. Amusement is tantamount, but these shows don’t ask much of the audience, and they certainly don’t challenge their fans. They’re perfect in the background, half-watched while sweeping the apartment. This is what I was expecting from Reacher: a mildly appealing series that required little of me, spoke to my mother’s televisual interests, and featured a tank of a man who was easy enough on the eyes. But swiftly after starting the series I realized there was something more complex about Reacher, a glaringly white fantasy that can’t help but crack under the weight of its conservative values. This isn’t merely hackneyed wallpaper TV; it’s uncanny fiction that exemplifies just how intensely Hollywood has returned to whiteness after years of feigning interest in diversity broadly and Blackness with a particular extricative zeal. Watching Reacher isn’t easygoing; it’s like watching a frightening manifestation of the free-falling American empire on a loop.

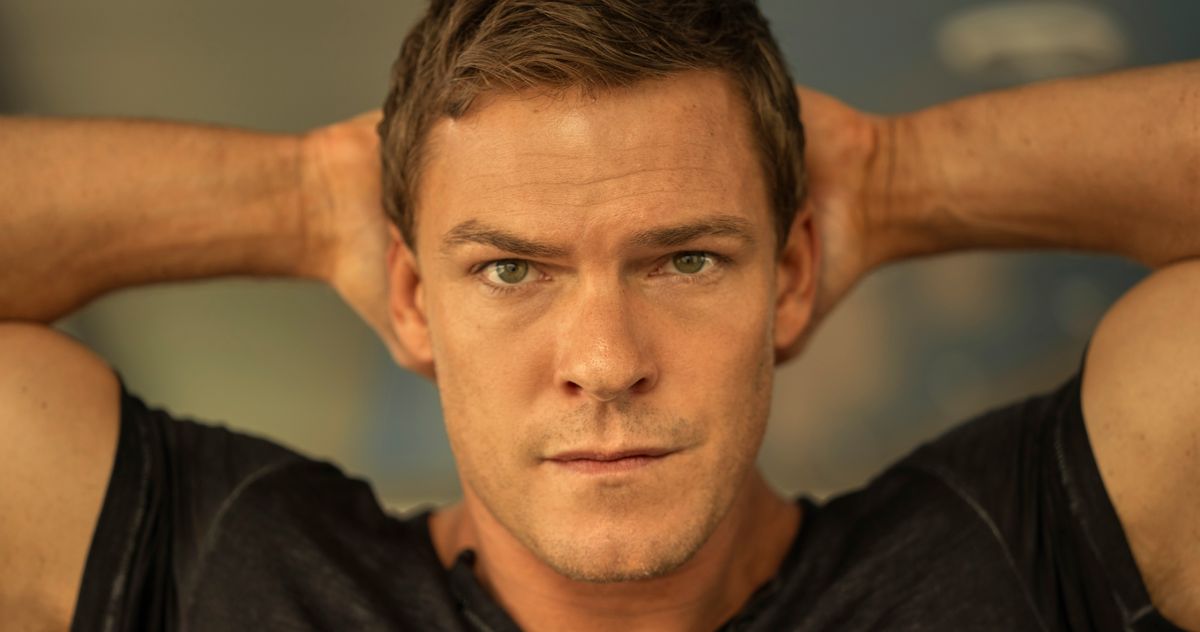

Based on the Lee Child novels and developed by Nick Santora, Reacher is the kind of series that exemplifies the sleight of hand the TV medium does best, beguiling with one set of beckoning fingers while smuggling complex propaganda with the other. My prior knowledge of this literary franchise was admittedly shallow, mostly informed by my experience of the dim Tom Cruise movies. But this Reacher adaptation is a different beast. And beast is exactly the right word for it — featuring as it does a Dodge Charger who’s achieved human form (actor Alan Ritchson). When Reacher, who refuses to be addressed by his first name, Jack, saunters into the fictional town of Margrave, Georgia, the show portrays his masculinity as exceedingly powerful yet good-natured; something to be obeyed but also preserved and exalted. In the premiere episode, Reacher wordlessly halts a domestic-abuse incident on his way into a diner, where, once inside, he doesn’t get to enjoy his cup of black coffee, or the slice of peach pie marketed as the best in the state, because he’s soon arrested for a murder he didn’t commit. He asserts his innocence at the police station, refusing to cooperate unless someone releases him from the zip ties encircling his wrists. (The handcuffs are too small, of course.) “Get the box cutter,” the routinely disrespected police chief says. “It’s okay. I got it,” Reacher says before popping the zip tie by sheer force. He picks up the fallen plastic. “Do you guys recycle?” A knowing smirk never leaves his face. Reacher knows that if a white man is tall enough, the world will bend to his whims.

It’s no surprise to learn someone like this — six-foot-three, all American-fried Hemsworth — lives off the grid, with ambiguously defined wealth that allows him to remain unrooted to any address and move through this procedurally minded series helping those he deems worthy. He is both inside the system (he’s a former U.S. Army military police major) and outside it (no one orders Reacher; he applies justice where he sees fit), recognizing corruption in governing bodies but ultimately believing in their worth and shoring up their value by acting as if their problems are the result of a few bad apples rather than full-blown environmental rot. He can size anyone up with ease, though it’s just as uncomplicated for him to bash a head in or shoot a person at point-blank range without blinking an eye. I lost count of how many times season-one Reacher kills someone or walks onto a crime scene without any badge or jurisdiction. He embodies the erroneous, conservative belief that the way to stop a bad guy with a gun is to have a good guy with an even bigger one. He is the show’s judge, jury, and executioner, and audiences love him for it.

As the central murder mystery heats up, Reacher develops a tepid romance with Margrave detective Roscoe Conklin (Willa Fitzgerald) and faces difficult memories of his late mother, all of which is muddled by a reveal that surprises even Reacher: that it was his brother, Joe, a former Secret Service member on the hunt for the truth hidden in Margrave, who was murdered in the premiere episode. His death is the connective tissue to which all the other murders Reacher encounters thereafter are linked. But Reacher’s most crucial relationship is with Oscar Finlay (Malcolm Goodwin), the Black police captain and chief detective from up north. As the season progresses, Reacher understands Finlay as both vital to squashing the conspiracies around his brother’s death and crucial for affirming Reacher’s superiority in the environs through which he moves. Reacher habitually refers to Finlay’s love of tweed, says he dresses like the Black Sherlock Holmes, and relays how Finlay’s underlings refer to him as a “Beantown Bitch.” There’s a sense that the word “uppity” remains unspoken in every instance, just on the tip of Reacher’s tongue. (A Harvard-educated negro, out of his depth, who doesn’t know his place in the schema of white society, needing the help of a real American? Is that a thinly veiled rejection of the Obama years?) The show handles racism — the kind Finlay would obviously face in a small, rural Georgia town run by fierce capitalist interests — by not handling it all: He just doesn’t face racism.

What’s wild about the show’s framing is that it is Reacher who bravely grapples with the town’s prejudices; alarmed faces crowd the sidewalk when he walks through town. In reality, white America loves itself a tall white man who can take charge and tell the government to go to hell. But Reacher needs tension. Finlay and Reacher become a study in opposing aesthetic and political forces. The latter is cool, charming, and collected, wearing jeans and T-shirts — the clothes of the people. The former is a bespoke and besuited bundle of nerves. “You always so confident in your theories?” Finlay accuses more than asks Reacher, who is quick to reply. “As confident as I am that you went to Harvard, you’re recently divorced, and you quit smoking in the last six months.” (Finlay’s wife is dead, for the record.) As Reacher rattles off more facts he’s gleaned about Finlay, he steps closer and closer to him. Until, finally, they are facing each other in the parking lot of the Margrave police station. Reacher towers over Finlay, in shot after shot over the season, as the camera lavishes attention on his physical magnitude and visually puts Finlay in his place.

Photo: Prime Video

Is it any wonder that Reacher has an entrenched right-wing fanbase? Is it any wonder Reacher has become the ultimate fable for how a certain kind of white male wishes to see himself? Is it any wonder the National Fraternal Order of Police would go apoplectic with social-media posts after 41-year-old Ritchson was profiled for The Hollywood Reporter and was candid about his own vulnerabilities and personal struggles: with suicidality, bipolar disorder, and his faith as a Christian? He was most blunt about his political beliefs: “Trump is a rapist and a con man, and yet the entire Christian church seems to treat him like he’s their poster child, and it’s unreal.” In reference to a shirt he wore in a 2020 Instagram post, which read “Arrest the Cops Who Killed Breonna Taylor,” the 26-year-old Black woman murdered by police in her Louisville, Kentucky, apartment, Ritchson responded, “Cops get away with murder all the time, and the fact that we can’t really hold them accountable for their improprieties is disturbing to me. We should completely reform the way that we do it. I mean, you shouldn’t have to spend more time getting an education as a hairstylist than as a cop who’s armed with a deadly weapon.”

After 9/11, the media reconstituted itself. Blackness was no longer used as a marker of countercultural cool; instead, Black people — but particularly Black men — became the face of institutions in a united-we-stand era from which we have yet to escape. They became police officers, lawyers, judges, and government workers in The Wire and beyond. In making Black people the face of the empire, shows and movies could garner diversity points while also projecting faith in systems that constrain the possibilities of Black life. Finlay is an extension of the fact that the roles for Black men in Hollywood have been winnowed down to, broadly, three types: the government worker, military man, or cop who can be anything from macho to sensitive, but who will always reaffirm the system; the Black neurotic, there to be a worrier and a receptacle for the white character’s anxieties, who allows the white character to seem cooler and more powerful in the process (see: Anthony Mackie as Falcon/the new Captain America in the MCU, Brian Tyree Henry in the Godzilla x Kong franchise and the unfortunate turn in Don Cheadle’s career, for starters); or the badass tactical-fighter type who is initially framed as enticingly radical but turns out to be evil and needs to be stopped (à la Michael B. Jordan’s Killmonger in Black Panther). Finlay is obviously a combination of the first two types. As a detective, he brings a Black face and implicit support to a white institution so primed on the exploitation of Black death. And as a high-strung individual, he works to make Reacher seem even more effortlessly adept. When Finlay largely disappears in season two, the series loses its propulsion, because without him as a foil, as an embodiment of the other, Reacher doesn’t have a character to define himself against. Whiteness always defines itself in opposition to the other.

The majority of the second season sees Reacher play against new characters (though Finlay does make one brief appearance beside Reacher, who can’t help but pop out another insult about a tweed suit because he’s got to remind Finlay of his position in the narrative, and the world) — primarily members of his former Army police investigation team, who are being mysteriously killed off. The Latinos and sole Black man of the group are seen mostly in flashbacks, so Reacher’s relationship to them is vague. Black and brown people seem to appear only to prove he’s a man who can move through any domain. The story avoids the specific, focused, noxious undertow of racism that powered the first season in favor of something more diffused. Which isn’t to say Reacher season two avoids its white fantasy. It remains centered on a surface-level critique of military and governmental malfeasance that in fact argues for the worth of these systems when men like Reacher are given free reign to dole out their idea of justice inside them or for them. In this way, Reacher is the most insidious example of television that fronts as wallpaper TV but is fueled by and fully displays toxic beliefs about power and America. Indeed, my mother found it to be fluffy entertainment, because that’s how it wants to be seen. A trifle whose poison goes down as smooth as expensive whiskey. Blackness may no longer be allowed to have its cool edge in Hollywood, but whiteness still has use for it.

:quality(85):extract_cover()/2023/06/22/813/n/1922283/b31cef376494937498fb49.96483599_.jpg)