In the Emmy-season premiere of The Envelope video podcast, we sit down with Maya Erskine, star of Amazon Prime Video’s acclaimed reimagination of “Mr. & Mrs. Smith,” and Viet Thanh Nguyen and Don McKellar, who brought Nguyen’s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel “The Sympathizer” to life on HBO.

Yvonne Villarreal: Hi, everyone. We’re deep in the heart of Emmy season, which means we’re back with The Envelope podcast. Thanks so much for joining us. I’m one of your hosts, Yvonne Villarreal, and I’m here with my friends, Shawn Finnie and Mark Olsen. Thanks for joining me.

Mark Olsen: Great to see you.

Shawn Finnie: Yes. We’re back. Did we leave?

Olsen: No. We’ve just been in this room the whole time.

Villarreal: I know what you guys are thinking: Emmys, again? Didn’t we just do this? But the ceremony in January was actually a result of delays from the dual writers’ and actors’ strikes, so this is actually the ceremony for this year. And, you know, there’s been some contraction in the television space, but that doesn’t make the task of going through the shows any less overwhelming. It’s still a massive list of shows. Shawn, I’m curious: You’re well versed in the film space, in the film awards season. How does this feel different for you?

Finnie: It feels very different. It feels, I mean, honestly, you kind of alluded to it. It just feels like a longer list, a more expanded list of content to get through. And obviously, the shows kind of overlapping each other didn’t really help. But also what’s interesting is I’m so used to like a — I don’t want to say “proper” awards season — but I’m so used to the gambit of festivals and how that goes into the official awards season. This feels just kind of like it’s happening in the ecosystem.

When you think about the film academy, it’s 11,000-plus members around the world, about 24 different categories in about 19 different disciplines within the organization. This, I believe, has like 24,000-plus members, 40-plus categories and 30-plus different disciplines that the body represents. So, from an administrative standpoint, it is almost equal to how expansive it is to me just getting through the content. And so I’m like, “I’m so glad that we’re doing this together so I can share.”

Villarreal: I mean, you made all that feel like an SAT question! Mark, how are you feeling?

Olsen: For me, as someone who’s more versed in the movie world, the thing that is confusing, Shawn, like you were just saying, is how awards season to me means festivals, all these other awards shows kind of leading up to it. It’s so interesting to me how even the Golden Globes, the [Screen Actors Guild] Awards, these other award shows that do give out television awards are still essentially in the runway to the Oscars. And so there aren’t stops along the way to the Emmys. We’re doing this, all the talent is out there doing their FYC events and everything, and then the Emmys happen. There’s not going to be as much buildup. I don’t know how you feel about it, but it seems like it also makes, for better or for worse, the horse race aspect of this — who’s really competing, who’s really got a shot here, who should we really be talking about or who are we overlooking — feels much more up to journalists and what they’re going to be covering. And so it makes the whole process feel a little more amorphous to me.

Villarreal: That’s why it’s so hard to get new shows in the mix, because it is easier to go off what we know, at least on the voter side I would imagine. This year, we’ve lost “Succession,” we’ve lost “Better Call Saul,” and some of the shows that were regularly in contention, like “The White Lotus,” they didn’t have new seasons during this time. So it does leave a little bit of room for new shows like “Mr. & Mrs. Smith” or whatever. And, you know, we’ve lost a few comedies. So it will be interesting who gets sort of in the mix.

We talked earlier too about the blurring of categories and what can be considered a drama or comedy. How are you feeling about that?

Finnie: I’m just glad that there’s a comedy category. I’ll just say that … To me, I’m getting used to all of these categories, that’s my honest answer. Mark, one of the things that you mentioned that was great is the SAG Awards, the Golden Globes — you think about the Oscars, you kind of feel like that prediction list that you start to see culminating and just going around is different, but also for a film to qualify [for the Oscars] it has to be in the theater. And so there’s still sometimes a community experience where you’re able to see how other people are reacting. For TV, for me, it’s more [of] a singular experience. And so that’s also been interesting.

Villarreal: And you’re committing more time to that singular experience. I mean, I know some movies go three hours now, but with TV shows you’re still dedicating eight hours, 10 hours of your life to it if you’re doing it right.

Finnie: If you’re doing it right.

Villarreal: With our next few episodes, we’ve got a lot of great contenders that are in the running. Mark, why don’t you talk to us about who you spoke with this week?

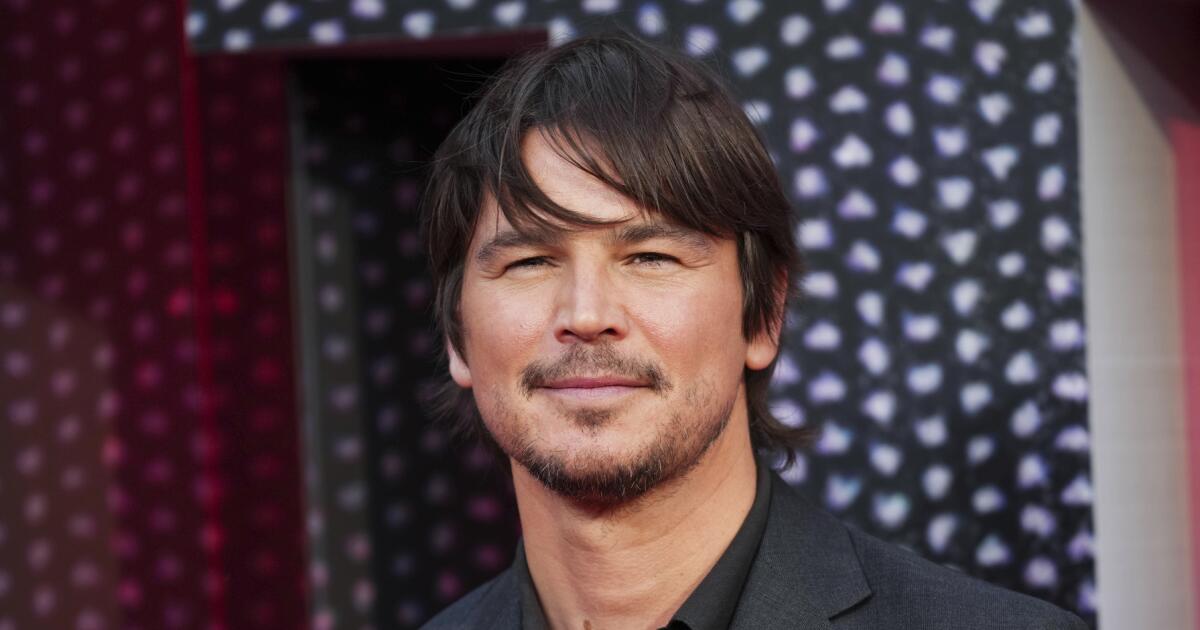

Olsen: I talked to Maya Erskine, one of the stars of “Mr. & Mrs. Smith.” And, you know, having kind of first broken through playing an awkward teenage version of herself in the semi-autobiographical “Pen15,” this is a very different Maya Erskine in “Mr. & Mrs. Smith.” Here she’s this very capable, stylish, sexy secret agent who takes on a new job, and she’s paired with a partner played by Donald Glover, who’s co-creator of the show. They begin as a professional relationship that becomes a more personal relationship, and it’s really interesting how the show, you know, it begins similar to the movie that it’s based on, as this kind of examination of a marriage and what relationships are like — but then the show also has a lot to say just about people’s relationship to work and what it’s like having a job in the contemporary economy. I think the show and Maya’s performance in particular was a real surprise.

Finnie: I’m glad they made it a series, and they continue to evolve who the characters can be and how reflective of the world that actually is. To your point, they talk about like, “OK, when are we cutting off work? We’re having dinner right now, we can’t be talking about—.” But then their phone goes off and they have to be a part of it. So yeah, I loved it.

Villarreal: Shawn, tell us who you spoke with.

Finnie: I spoke with Viet Thanh Nguyen and Don McKellar, who are two of the three creative forces behind “The Sympathizer.” Viet is a Pulitzer Prize winner, and I think it’s nice having the author whose content it was adapted from really be a part of the experience. He’s an executive producer too, so I got to speak to him about that and what that was like. Obviously, Don McKellar has been a part of this game for a while, but “The Sympathizer” is really about a communist in South Vietnam, and it’s really based on loyalty, identity. And more importantly, I think we’ve always seen the Vietnam War from a very Western lens. But we got to see it [here] from the Vietnamese experience, and I think that that was really, really cool. And they talked about how it was so important for them to make sure that they had Vietnamese representation, authentic representation on there too. So it was really, really good. And I loved hearing more about how things happened on set.

Villarreal: After this break, we’ll get into Mark’s conversation with Maya Erskine.

Maya Erskine in “Mr. & Mrs. Smith.”

(David Lee / Prime Video)

Mark Olsen: I’m here today with Maya Erskine, one of the stars of “Mr. & Mrs. Smith.” Thank you so much for joining us.

Maya Erskine: Thank you for having me.

Olsen: On the show, your sort-of employer always opens their messages with “hi, hi.” And you begin referring to them as “Hi-hi.” And I have to confess, watching the show, I began compulsively saying hi-hi. And I don’t know if other people have had this response.

Erskine: There have been multiple people. A lot of the crew members were saying, “hi, hi.” When we would just be saying our salutations, it would be “Hi, hi.” But yeah, but then it sort of tapered out by the end.

Olsen: In remaking the 2005 movie “Mr. and Mrs. Smith,” I think people expected for it to be an examination of marriage. But one of the things that I think has made this version feel so fresh and really contemporary is it also is very much an examination of work and the gig economy and people having kind of transient jobs nowadays. Was that something that jumped out to you when you first were reading the script?

Erskine: The way that it was initially described was actually like a cross of “Scenes From a Marriage” and “Annie Hall.” The focus was so much on the relationship and showing the really in-between moments of relationships that you don’t get to explore all the time — and the nuances. Then as we were filming it and the scripts were being written, I started to see like, “Oh yeah, it is showing this other side of work and these temporary jobs.” And then also sort of what it’s like to be in work with your spouse, with a partner, and how that can affect your relationship; how one person’s successes can make the other person feel really insecure. Like all of those elements were such a big part that I fell more in love with as we were filming.

Olsen: You got excited about that as that part of it was coming out.

Erskine: I knew what the goalposts were going to be, like the first time you date someone, the first time you go on a trip with them. I knew that. But I feel like as they kept writing it and as we kept filming it, it would get deeper into the dynamics of what it means when the woman is saving the man constantly, or doing a little bit better, or getting a promotion. How does that affect the relationship? And that was exciting to me.

Olsen: There’s something really glamorous and sort of luxurious about the world of the show and in a lot of ways, it just highlights how like impossibly out of reach that is for many people. How did you kind of respond to the world that the show exists in?

Erskine: In the first moments of the pilot, you know, you’re walking into this impossible-to- attain brownstone in New York, West Village, that I’ll never step my foot into, and the closet and all these clothes and even just the filming aspect of it for me felt like such a big, hard-to-attain place to be because we were filming in Italy and in the Alps and we were filming in Lake Como and it was just this massive production and this really high production value. And it’s just little old us like in these shots that are grand and sweeping. And so yeah, it sort of started to mirror the actual action of filming the show. That was a true intention of [co-creator] Francesca [Sloane] and [co-star] Donald and [executive producer] Hiro Murai when they were filming.

Olsen: Your background is kind of in independent film and on “PEN15,” which is kind of a scrappier show. What was it like? You’ve never quite, I think, worked on a production at this scale before.

Erskine: Never. Even with Donald, the way they’ve described working on “Atlanta,” they weren’t big budgets, so it always felt like students coming together to like make their project and make something happen. And what I was so nervous of was when something is really big, you can sometimes lose touch with that sort of fire and that passion to like, really make sure we get every shot that we want. And that was never gone. It was present from the whole time, from the beginning to the end. I’ve talked about this before, but Fran, Hiro and Donald and I were walking on the street on one of the first days. It was in Tribeca. It was a night shoot. There’s huge cranes, huge lights everywhere. And we were just like, “Oh, this is for us.” Like, “I can’t believe we get to do this. Who allowed us to?” And so it felt like being a kid in a candy shop the whole time. But we never lost that drive to really make it as specific and nuanced and as good as we possibly could.

Olsen: And now, Donald Glover, your co-star and the co-creator of this show, his public persona is very enigmatic. And I’m curious what it’s like for you to then meet him in a bit of a rush and in a lot of ways get to know him through the course of making the show.

Erskine: He surprised me so much because he’s so easy to get along with. He’s so warm and so down to earth and passionate. And I was definitely intimidated at first, but it worked out well because, you know, in the beginning of the show, we don’t know each other. We’re strangers. And so I think it lent itself really well to the chemistry of just getting to know each other. And we were kind of having our professional faces on in the beginning. But then as we were filming, there was so much modulating of like, “How much are you revealing? How vulnerable are you getting with each other?” And we were constantly playing with that. So at some point, Donald and I just started sharing embarrassing stories about ourselves to each other, and it was like, “OK, good. I can say that.” It just opened it up and we were like very, very good friends after that. We got very close as it went on.

Olsen: The characters of John and Jane approach their work very differently. Jane is much more sort of planned out. She’s almost administrative, in a way. John is much more improvisational and emotional. Does that describe you and Donald as well?

Erskine: Weirdly, yeah. I do think he is better at staying in the moment. Like, he’s extremely present. And I am thinking about the future constantly. I’m just constantly like, “All right, well what’s the scene tomorrow?” I’m just constantly thinking about it, which isn’t healthy. But that’s how I operate. And so it sort of mirrored what we were doing as our characters in terms of planning and being organized. And I’d be like, “You know, we have to shoot this scene tomorrow.” He’s like, “What? What scene is that?” But it was great. It worked. We balanced each other out. It was a good partnership.

Olsen: Before the show came out, there was a lot of press around the fact that Phoebe Waller-Bridge had been attached to it and left the project. And then you came in. How was the character reconfigured for you, or what sort of impact do you feel like you had on the character?

Erskine: I don’t know exactly how it was written before I came on because they didn’t share any scripts with me, so I can’t speak to how it changed from that. But I do know that once I was involved, they asked me to share stories of my relationships, insecurities, any quirks that could help infuse the character Jane with parts of myself. But she still felt actually closer to the showrunner [Francesca Sloane] in a lot of ways. Like, the more I got to know the showrunner, I was like, “Oh, I feel like she’s you, and I’m just, like, joining with you.” Because it was from her voice.

Olsen: How so? What is it about the character of Jane that you think is like Francesca?

Erskine: I don’t want to say anything getting into specifics about Francesca’s life or her personal relationship, but there’s things that are drawn from her relationship, from Donald’s, a couple things from my relationships, past relationships. The thing about Fran is just how incredibly strong she is. She’s a little bit more vulnerable and able to express her emotions, I think, than Jane is in the beginning. But she can have a searing edge to her if she needs to. She’s incredibly intelligent, but I would say warmer than Jane.

Olsen: Both you and Donald are incredible physical performers and in particular in the finale, the house shootout, there’s almost this “Looney Tunes” aspect to it. Was that a way that you felt like the two of, you and Donald, connected? You both seemed to have this very elastic physicality.

Erskine: I am a physical actor. That is how I approach characters — I have to come from the physicality first. And so actually in the beginning it was tough because we shot in order. So the first episode, it’s a lot of stillness and there’s only some running. There’s just a lot of keeping your cards close to your chest: How much do you reveal, how much do you not reveal? And that’s really hard for me because I’m not good at lying. And I want to express everything all the time. And I’m an oversharer. The final episode, where we finally get to, like, really release all of it, Donald and I just had so much fun with it.

Olsen: Is there a distinction between physical comedy and physical action, like stunt work? Like, are those kind of the same or is there something distinct about them?

Erskine: The thing with both is it’s just being aware of your body and being present in your body. If you can do that, then it’s like it’s a malleable instrument that you’re just using in different ways. And I think with physical comedy, the intention is never to be funny with your body. It’s sort of like, “I’m just doing this thing of my instinct or whatever, and I’m playing this character and this is coming out right now.” But it’s not like, “Let me do a funny move.” It’s more just, I think for me at least, “This is how my body is manifesting whatever I’m feeling inside.” Maya from “PEN15” is like an extremely physically wild character. And I feel like for that, that was just me remembering what it was like to be 13 and letting that play out — not stopping the instinct from happening.

Olsen: The show also has this kind of real casual sexiness to it. There’s a scene where the two of you were at a farmers market and you’re wearing just a slip dress with a shirt over it, Donald has a couple buttons too many unbuttoned. And that aspect of the show is one of the things that makes it really appealing and like a very fun hang. Did you get really involved in the costuming and what Jane was going to wear?

Erskine: There was a lot of back and forth in the beginning, deciding what her look was going to be. We had a lot of references to Jane Birkin and kind of going in that direction, but then sometimes going more masculine. It was always just a constant conversation. But I think the goal was always for simplicity. Simplicity and ease is what can be very sexy. Not like these sculpting bustiers or what you think of when you think the word “sexy.”

Olsen: This is a video podcast. People can see the fact that you’re currently pregnant.

Erskine: Yes.

Olsen: And I’m curious: It’s such a big story point in the show. There are so many conversations about whether to have a baby right now. I know this is your second child, but did that somehow crystallize your thinking or your feeling on this topic? It’s so curious coming along when it is.

Erskine: I always knew I wanted to have more kids. And so when filming it, it was more about the challenge of having to represent the other side in the fight: “I don’t want kids.” And trying to get in that mindset of what that feels like. She comes up with reasonable justifications for why she doesn’t want to have kids. In my mind, though, I think she does want to have kids, deep down. She just thinks that it’s not the smartest timing in this job.

Olsen: That is something that’s so interesting, again, in the distinctions that are drawn between John and Jane. She has a much more sort of conventional ambition. Like, she wants to move up the ladder. And he doesn’t.

Erskine: I think also it’s the family that he grew up in and the family she grew up in. She doesn’t have a warm relationship with the one surviving parent, her father. She doesn’t have this model to go off of, of a healthy family life. And she lost her mother when she was young. So in her mind, she’s like, all I need is really just this cat and a job and money, and then I’ll be fine and then I’ll run off and I don’t need you. I don’t need anyone. Like, that’s sort of her armor and her way to survive in life. And so I think adding a kid, that would be this huge, foreign object in her mode of life, her mode of thinking, how she survives. She can’t even fathom bringing that in, in this moment. John is someone who he still talks to his mom every day. And I think he’s here because he wants to have the nice life. He wants to have the house. He’d be happy being the lower risk, you know? What are we calling it? The lower risk of hi-hi. Just so that he could be able to come home every night, cook dinner, have a kid, put them to bed, just live the all-American life. And that’s not enough for her, I think, in her mind.

Olsen: Donald’s mother plays his mother on the show, and curiously, your mother played your mother on “PEN15.” What is the energy like on set on a mom day?

Erskine: It’s really fun. I mean, she was great. Beverly’s great. She made it so easy. And it just brings a warmth and shows another dimension to whoever’s parent it is. So you get to see this other side of Donald, how he acts with his mom. And it’s very sweet. For me, I feel like I was, such a brat and a child around my mom. I’d be like, “Mom, it’s continuity. You can’t hold your bag now like that, God.” But I love having family on set, and it was a very family-oriented show. We all had kids, and it was great.

Olsen: As we’re recording this, coming up is the Tribeca Film Festival. And your husband, Michael Angarano, has a film, “Sacramento,” that’s premiering there that you’re in. As I understand it, the two of you met through the process of making this movie.

Erskine: This was years ago. He had offered me a part in it and I said yes, because I was a fan of the script and his work, and then we didn’t meet for, like, months. And then finally we had a meeting and then just kept kind of hanging out. And the movie didn’t get made until after we had a kid and were together. What’s crazy is that the movie is about us meeting and having a kid, and it actually happened.

Olsen: I would imagine it represents a definite chapter in your relationship and this movie is actually now done and soon to be in the world. I’m just so curious, what that does for the two of you. It’s almost like you’re in a new phase of life.

Erskine: It’s a really touching, beautiful part of our life. It was so lovely making the film. It was so nice. When he did the buyers screening, it was on our son’s birthday and there were just so many moments that we would look at each other like, “Wow, this brought us together. This is our our family. This is our life now.” And he did such a beautiful job directing it and making it, and I’m just so proud of him.

Olsen: To get back to talking about [Mr. & Mrs. Smith], did you have, like, a map? How did you determine the extent to which Jane and John had like a real relationship at any point in the show? Because it does seem like at first they’re sort of play acting as a couple because that’s their job, but then it quickly becomes a real relationship. There’s one scene in particular after he’s been out in the snow, a bathtub scene where you say, “I really, really care for you.” And the emphasis of the two “reallys” was to me very emotional and really startling. And I’m just curious, for you, how did you decide how much she did or didn’t care for him or really was or was not in the relationship at any moment?

Erskine: What’s interesting is that episode we filmed at the end of the whole series. That was the one that was out of order the most. So we were like, very comfortable with each other by that point and that scene in particular, I’m so glad you mentioned it, that came from a real moment that happened between Donald and his wife, when there was that sort of defining scene of, “Wow, I know, but I really, really care about you.” Like, “It’s frightening. And I don’t like how much I care about you.” It was tough to figure out how close they get, how fast, because we are jumping in time. And so I was always very careful about wanting to make sure I wasn’t either exposing too much or being too intimate. Sometimes we would have too much chemistry and it would seem like we’re a couple already, but we’re just starting. Like, what is it like when you first get in a relationship with someone? What is it like when you travel with someone and you fart in front of them for the first time, or they see you brushing your teeth and all of these intimacies? For me, that was my favorite part of the filming, was just finding all of those, like, nuanced moments and those touchstones. And yeah, when we filmed that scene in particular, I remember we did the rehearsal and it was very emotional during the rehearsal. It is such a sweet way for Jane to expose that she actually really cares about this person and likes them.

Olsen: As genuine and emotional as the show can be, it also is extremely credible as a fun action show; the Lake Como episode in particular, with Ron Perlman, the whole sequence where you’re up and down a lot of stairs. What was it like shooting that sequence?

Erskine: It’s wild, action scene sequences, how you have to film them and how many times. … You’re shooting in a real car with someone driving on top and controlling it, or you’re shooting on a stage. There’s so many times you’re filming it, it can feel very mechanical and and exhausting. But it’s also, for me, freeing, because sometimes it’s nice to not have to think at all in a lot of ways. And you’re just in your body. So I loved it, and I love Ron Perlman so much. He’s amazing.

Olsen: As much as the show is focused on the characters of John and Jane, on you and Donald, there’s an astonishing deep bench of supporting players that come through. What was that experience like there? Like, you know, one day at work, Ron Perlman or Sarah Paulson or Parker Posey and Wagner Moura. What was it like having those supporting players coming through?

Erskine: It’s all my favorite actors. It’s all my heroes. I’m just like, “Great, thank you. This is so nice.” I mean, it’s one thing to have watched them all, I’ve watched so many of their movies and shows. And so then when you actually get to be in person with them, acting opposite them and getting to see their process live, it’s just it’s such a treat. And I thought I would be terrified and not be able to hold my own or act with them — that I would just, like, hide in a corner. But they’re so warm and inviting that it was just like, it just felt like actors just working together. Easy.

Olsen: Do you feel like you learned anything? Like, can you steal anything from Parker Posey?

Erskine: I love how she just goes into it. I love that she’s not very precious in between. She’s kind of just, like, talking and we’re just hanging out and then all of a sudden can just, like, sort of jump in. But the energy, her energy is always really up and really [she] just gives something different every time. So, I mean, that’s what I saw and that’s what I try to do.

Olsen: You mentioned the possibility of a second season, and I’ve heard you in some other interviews having to be somewhat politely evasive on this question. What can you or can you not say? Because I’ve heard you say that you know some things.

Erskine: I do.

Olsen: Now, you can’t say that to a group of journalists —

Erskine: I’m sorry, I’m not good at that. I mean, they could change it. I don’t know, they could change whatever they told me. I think it’s going to be even better than the first. That’s what I would say. It’s very exciting what they have in store. And that’s all I’ll say.

Olsen: The way the show ends on such a kind of ambiguous note, were you surprised by that ending? What do you make of the ending?

Erskine: I loved that ending, I love it. … Francesca Sloane, the showrunner, she said, “It depends how you look at life.” Like, if you’re a glass half-full or glass half-empty [person]. How do you look at it? Maybe they both survive. Or maybe one survives. Maybe just Jane survives. Maybe just Donald survives. John. I have my own feelings of what I think happened. It might not coincide with what is going to happen in the second season. But I think it’s a brilliant ending. I loved it.

Olsen: So are you a glass half-full or glass half-empty kind of person?

Erskine: I am a glass half-empty kind of person, but I also thought this was only going to be one season, if I’m going to be honest. I really did think it was a limited series. So I was like, “Oh, it’s just one and done.” So I thought that they both died, but I don’t know what happened.

Olsen: But people want a second season.

Erskine: I mean, I’m not saying that’s what happened or that’s what didn’t happen. I’m just saying that’s where my mind went. Or I think Jane survives in that moment.

Olsen: I have to ask you. In the course of the show, Jane, as you said, doesn’t really have any family, she just has this cat. And then in the final episode, the cat gets shot in a firefight. I myself have a cat. I am ridiculously attached to my cat, and so that’s messed up. You can’t do that.

Erskine: You can’t do that. That’s crossing a line. But it wasn’t him. But she thought it was. But yeah, it’s crossing a line. I know, it’s dark, but it has to go to that place in order for them to hate each other that much, to want to kill each other. It has to get that dirty, I think.

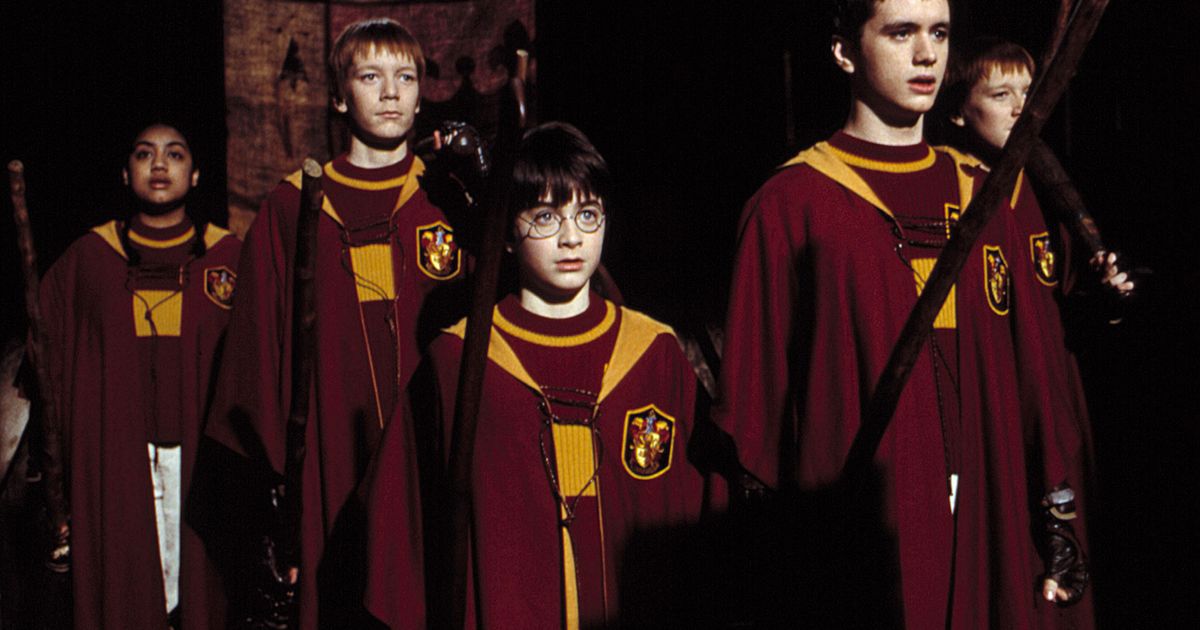

Hoa Xuande and Robert Downey Jr. in “The Sympathizer.”

(Hopper Stone / HBO)

Shawn Finnie: Welcome back to The Envelope. My name is Shawn Finnie, and I’m here with two of the creative engineers of the show “The Sympathizer.” I’m here with Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist and executive producer Viet Thanh Nguyen as well as creative force Don McKellar, who is co-showrunner and executive producer. I have questions for the both of you and questions for each of you individually, but I feel like we should start with you, Viet, because it starts with you.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: I would hope so.

Finnie: I love the idea of you telling an honest global story to a global audience. And my question to you is two-part. First, did you think any of your books would be adapted? And did you think it would be this one?

Nguyen: Honestly? No. Never. Because I was telling a story that was going to be as honest as I possibly could make it and, you know, setting out to offend everybody. And that’s not actually a good formula to have Hollywood come and hook into a movie. But if any book was going to be adapted, it was going to be this one, because the way that people understand it is that it’s a Vietnam War story. It’s a lot more than that, but that’s the hook. And Americans have an obsession with the Vietnam War. And I think the reason why that’s important is because even though it’s an American story for Americans, because of Americans’ power, it becomes a global story.

Finnie: How would you summarize your experience as an executive producer?

Nguyen: It’s been surprisingly good because I think I know how bad it can possibly get. But, you know, working with people like Don was really amazing. The most important part about being an executive producer was just trying to get this show made in the first place and then getting the right collaborators, because I knew I would have to turn the novel over to many other people. And so that was really crucial, to pick the right people, so that I could trust their aesthetic and political visions about the story.

Finnie: I love that which brought you to director Park Chan-wook as well.

Don, I want to get into you because you’re no stranger to all sectors of entertainment: theater, writing, directing, producing, acting. I’m so curious how all of those elements specifically prepare you. I feel like it gives you an advantage to really understand the nuances of a production. How did that really impact “The Sympathizer” and your experience?

Don McKellar: Well, that’s complicated. I mean, I’m showrunner for this series, co-showrunning with Park Chan-wook, and it’s true that I do feel that the acting, the writing, the the directing, they all come into play in that job. I definitely felt I could empathize with the actors a little more. … It all comes together, right? Because I’m also talking to the directors and trying to make a coherent sort of stylistic vision. I think the background helped.

Finnie: And I feel like, you know, we’re so used to seeing a version of this story told from a specific lens, a specific American, Western lens. I really would love to understand the importance of really making sure that you’re telling that global story honestly from a global perspective, specifically from the individuals that were impacted.

Nguyen: For me, the red line was that the story had to be about Vietnamese people, with Vietnamese actors speaking as much of the Vietnamese language as we could possibly fit in there. And if we were to do a show where the actors were speaking English with a Vietnamese accent, no. I was taking my name off of it. If we had a show with non-Vietnamese people playing these roles, I would have taken my name off of it. If we had a show where the white guy was the absolute center of the story, I would have taken my name off the show. So that was really, really crucial. And I think it’s taken a long time for Hollywood to catch up with the global story, with people like me and the stories that I’d wanted to tell. So I think maybe there was a window of opportunity and we seized it basically with this story, with these actors.

McKellar: That’s the first biggest hook. It sounds crass to put that way. But when you read the book, you think, “Oh, wow, I’ve really never seen it from this perspective.” The Vietnam War took place in this country, but I’ve never seen it from a Vietnamese perspective, which is sort of amazing. And I do think it’s a unique war that we really feel we know what it was like over there because of, basically, American movies. And so it’s immediately fascinating, at least it was to me, because I’m not Vietnamese, and I’ve never thought of it that way. But at the same time, because it’s a very good book, I could really get into it and understand it. And I felt a personal connection with it. So I thought, if I can help convey that very specific Vietnamese story to a global audience, I’m in. And yeah, I had the same conditions as Viet. Absolutely. We didn’t have to fight about that.

Finnie: And I think even the best books, you know, might sell thousands of copies. But when you think about TV, film and media, it has the span to reach millions. I’d love to talk about, from book to script to production, keeping the authenticity of the unique voice that is the Captain, played by an incredible actor, Hoa Xuande.

Nguyen: I mean, obviously, I think a book is awesome.

McKellar: [Laughs] He’s taken offense when you said —

Nguyen: When we were going to adapt it, I knew exactly what was going to happen, which is that everybody would be like, “Oh my God, congratulations. It’s going to be a TV show.” I remember people saying that about the book when it was published. So I understand the realities of the media landscape and the power of pop culture, especially in TV and movies. So there was a real responsibility on my part to try to get it as faithful to the novel as possible, but also allow the collaborators to realize their vision cinematically at the same time. So that was really important. And Don’s been a good collaborator. I remember our first meeting at a hotel, where we sat down and we discussed, “How are we going to [take] this novel and break it down into however many episodes?” And so we spent time talking about the story arc and however many many episodes. And, Don, I still haven’t forgiven you.

McKellar: [Laughs]

Nguyen: You said seven episodes was the right number.

McKellar: Yeah.

Nguyen: And I get paid per episode.

Finnie: [Laughs] Oh, you’re like, “Let’s just make this ongoing. It never ends!”

McKellar: You agreed to it at the time.

Nguyen: Artistic integrity, right?

But then Don really took over as obviously the head writer and co-showrunner. Assembled the writers room. That was a really interesting process for me, to see how he did that.

McKellar: It’s of course scary adapting a book. … I’m sort of intimidated by that. I love the book, and it’s impressive as a book. But on the other hand, as he said, it’s full of pop cultural references. It’s full of really cinematic sequences — even in the book. So right away I thought, “OK, he’s not going to be some stuffy writer who who will pooh-pooh ideas that come up that we think are cool cinematic ideas. That’s part of it because it’s about storytelling and it’s about how we’ve perceived the Vietnam War through stories. So if he wasn’t open to that, we would have had a problem too. So that collaboration went both ways.

Finnie: I believe that you were going to shoot it in Vietnam, but ended up shooting in Thailand. What was it like, building Vietnam in Thailand?

McKellar: We tried to shoot it in Vietnam. We tried pretty hard. We weren’t exactly rejected. … The book, is it actually banned? Can I say that?

Nguyen: I think the book is soft-banned. I mean, there’s no official list of banned books, as far as I’m aware, but we’ve had a translation for about seven or eight years, and we can’t get permission to publish.

McKellar: The book is really well known in Vietnam, that’s for sure. Everyone I talked to knew it. But it’s not officially published in Vietnamese, so it’s complicated. And we weren’t officially banned either from shooting in Vietnam, but there was a lot of bureaucracy. It was going to take time. They made that very clear. The fortunate thing is, Thailand is very well structured [for production]. It has a lot of equipment and crew and experience shooting shows this size. It was not easy duplicating Saigon in Bangkok. We had to go to a lot of smaller cities trying to find period-looking buildings and buildings that had, at least suggested, a colonial background, which Thailand doesn’t have. So was not easy, actually. And it took a lot of work. But I’m pretty proud of the results.

Finnie: Viet approves.

Nguyen: More importantly, I think the internet approves.

McKellar: Even Vietnamese are pretty impressed. They think we shot some stuff there.

Finnie: I’m fascinated with the choreography, not only between you two, but also director Park and what that experience was like. Talk me through, in very simple terms, how you all actually worked together.

McKellar: I had worked with Park Chan-wook before this. I had written a feature script with him a long time ago. So I knew that I worked well with him and that we shared a taste.

Nguyen: It was an assembly line. We had to pull all the components together. … Park Chan-wook showed up at my house at our second meeting —

McKellar: He was invited [laughs].

Nguyen: he showed up and he had clearly read the novel, because he had very detailed questions and suggestions and like, “Well, why didn’t you do this?” And I was like, “Well, you should have been there five, 10 years ago.” That was really powerful because, besides being a director and so on, obviously he’s a storyteller. He writes the scripts. And so he’s very interested in the details of all the different things about character, plot, setting and all that. So he had an active role.

McKellar: Just to be clear, he loved the book. I knew that from the first time I talked to him. He was excited. It was a kind of thing that he said he’s wanted to do but hasn’t been given. He loved the sort of irreverence and the fact that it was an immigrant story, which he responded to, but not in a sentimental way that he was used to. He said he’d had a lot of scripts already that were in that milieu, but not to his taste. So he was very enthusiastic right from the beginning.

Nguyen: I think taste is important, because, you know, I was a big fan of Park chan-wook’s work before he came into my life. His movie “Oldboy” was a stylistic influence on “The Sympathizer.” And then I saw “The Handmaiden” after “The Sympathizer” was published, and I thought, “Wow, the visual language that he has, the spectacular imagery that he deploys and his understanding of history, colonialism, politics, warfare, imperialism — I mean, this is the word he used. We did an interview together for the Emmys, and someone asked him, “What drew you to this book?” And he said, “You can draw parallels between Korea and Vietnam in the 20th century,” and he used the word imperialism. He was in. And I”m like, “We’re the same.”

McKellar: Surely you weren’t shocked by it.

Nguyen: He said it in public without hearing it from me. He and I share similar tastes in terms of aesthetics, but also our sense of history and politics.

McKellar: To be honest, it wasn’t until he was involved that I really thought I could see the voice of the book being translated onto screen. It immediately made sense to me because of his politics and just his style, and his sort of fearlessness.

Finnie: One of the things that stuck out to me is the editing: the storytelling in reverse, the storytelling in the present and future-projecting as well. And I would like to talk about that — those decisions that were being made, obviously, in the book, but also stylistically, what we see visually.

McKellar: We had to find a way to do that that was cinematic. It’s harder. It’s easy in a book, in just in a sentence or two, to find yourself back in time. But in a movie, it’s harder. So we came up with this sort of filmic idea, this sort of rewind idea, that he’s almost editing his story. So he’s kind of a filmmaker, which sort of, put him on our level. And then I think at the very beginning, in the first episode, we wanted people to question why he was starting where he was. He’s told to start there by his interrogator. We wanted viewers to be thinking, “Well, why is he starting there? Why do they want him to start there?” And hopefully that pays off.

Finnie: I like the quote in the beginning …

Nguyen: All wars are fought twice, the first time on the battlefield, the second time in memory.

Finnie: That stuck out with me. But it also, for me as a viewer, prepared me for going back. Which is why I wanted to ask that question, because I was like, “It was so thoughtful.”

McKellar: It is about memory too. I think one of the great things about the book, again, is that, in a lot of Vietnam War- themed things, it’s really about the atrocities of war that we’ve seen, the absurdity of the American involvement. But this is really about the consequences of that and the legacy on these individuals, but also, on their memories that they’re carrying with them. And that became really important thematically to us. Because that’s the way the story is told. And it’s still present in their psyches.

Nguyen: It’s from another book called “Nothing Ever Dies.” Yeah. And that wasn’t actually planned. It was quite late in the game, someone suggested maybe we needed some kind of frame to introduce [viewers] into the story, because, interestingly enough, even though the Vietnam War ended only about 50 years ago, that’s ancient history for most people.

Finnie: Speaking of things unplanned, you were in an episode as well. I would love to hear a bit more about your unplanned cameo and one-liner. You’re an actor now too.

Nguyen: I think it’s kind of a tradition to put the author into whatever the production is, you know, Stan Lee and John Le Carré and so on. It was actually a really fun experience for me, although I didn’t get the role that I wanted.

McKellar: Here we go again.

Nguyen: I said, “I want to be blown up because that’s the fate of the author in his own adaptation.” But they had a more sophisticated idea, so I’m cast as a photographer in a restaurant scene where I’m taking a photograph of the entire cast. It’s a longevity banquet. Yep. And I was always supposed to go there and take the photo, and that took two days, because I had to get hair, makeup, clothing and then show up and all day shoot for literally was supposed to be — I wasn’t supposed to say anything. I realized how much improvisation takes place. And director Park was like, “Well, maybe we should have you speak a line.” I think [Don] wrote it on the spur of the moment. … It’s like three quarters of a second that I show up, but nevertheless I spoke. So therefore they had to pay me.

McKellar: Now that I’m thinking of it, we should have just blown you up at the end of the scene [Laughs].

Finnie: I believe Hoa Xuande, who plays the Captain, auditioned for about nine months. Tell me about that process and when you all knew that he was the person.

McKellar: I’s a big role. He really does carry the series. Like in the book, it’s from his perspective. He was in every day except for one and in that day there was an actor playing him as a child. He is really all over it, so we knew we had to get someone really good. And it’s difficult also because he has to be like a movie star, be this charismatic kind of spy like a ‘70s male spy from Hollywood except Vietnamese. And he also had to show him vulnerability. There’s quite a huge acting range if you see the whole thing. So we auditioned him a lot of times. I know he’s out there telling the world how we tortured him. And it’s probably true. We really did. He’s from Australia. He sent in his tape to a casting agent several times. We flew him to Korea to meet with Park Chan-wook. We flew him to L.A. to meet the two of us. … Now that I see him, I don’t know why it took us so long, but of course we had to have everyone on board.

Nguyen: I think it’s very meta because, as you know from the very first minutes of the first episode, he’s being tortured. He’s constantly being asked to repeat, revise, do over to the satisfaction of his interrogator.

McKellar: I did say in the final Zoom call when I gave him the part, “Remember how you feel now because you can use that as a sense memory.”

Finnie: And then the incredible Robert Downey Jr. — the Academy Award-winning Robert Downey Jr. — playing multiple roles. Was he always going to play multiple roles from the beginning?

Nguyen: That was all Park Chan-wook. … He said, “What if we made one white guy play all the white guys?” And it was like, “Wow, that’s a stroke of genius.”

McKellar: We discussed it before. It didn’t come up accidentally. And we were a little afraid what Viet would say, because it’s a kind of a crazy idea. You know, the precedent is sort of Peter Sellers and in “Dr. Strangelove.” We loved it because we felt that there were these recurrent older, patriarchal American white guys in the Captain’s life in the book and they come up almost as a sort of motif. They’re all very different. They’re all very different ideologically. But at one point in the book, they are all literally represented as all in the same club. And we wanted to show that’s not an accident, the similarity, that they’re all complicit in a way and that they’re all working together in some way, even more than they understand. So he came up with this idea of making it one actor and making that sort of the thematic point. And there’s also a sort of psychological point that comes up as the series continues: how the captain perceives them all and how he deals with them all.

Nguyen: Robert Downey Jr., was he the first?

McKellar: When we thought of that idea, it’s like, well, who’s going to do that? It’s a pretty small list, because it has to be a very technically accomplished actor and he’s got to play many different roles.There are great actors who are always the same, you know, who don’t like that kind of thing. And so, yeah, it was like Robert Downey Jr. and I think we had a couple of other names following that. But he was on board, amazingly, and that was that.

Finnie: One of the things, going back to the Captain, is I believe Hoa Xuande, who’s Australian, didn’t speak Vietnamese. So then he was like in a crash course. Talk to me about that process because like you said, it was important to be able to center Vietnamese actors speaking Vietnamese.

Nguyen: It’s part of the casting process. And, you know, we have to look at history here. There’s 90 million people in Vietnam, 4 million Vietnamese people in the diaspora. And the reason they’re there is because of the war and the aftermath. And, you know, you’re doing this global search for actors and everything and the criteria is pretty specific. They have to be Vietnamese in origin of some kind, and they have to be fluent in English, and they have to be able to speak Vietnamese, and they have to be the right age, which for the Blood brothers is around their early 30s. And that really narrows your pool down. And then in Vietnam itself, I think we couldn’t audition a lot of actors because a lot of them did not want to audition.

Finnie: Why?

McKellar: Being associated with this show, because of the sort of reputation of the book, could harm their livelihood.

Nguyen: So those folks obviously speak fluent Vietnamese. Whether they could speak fluent English we never really found out.

McKellar: Many of them couldn’t, right? That’s part of the problem. He has to speak very fluent English and Vietnamese. …

Nguyen: The basic reality is this entire generation that’s been born outside of the country, oftentimes their Vietnamese is shaky to nonexistent.

Finnie: And the lingo, he had to really understand it.

McKellar: You’re right. It’s not casual Vietnamese. He’s got to talk about war-specific terms and communist lingo. It’s not casual, chatty Vietnamese.

Nguyen: We had a lot of people working on the Vietnamese aspect. I think it was at least two or three people on set, at least one person working on the script off the set. My former Vietnamese-language professor was consulting after everything was done in ADR. There’s at least a dozen Vietnamese actors on the ADR trying to do things after the shooting was finished.

McKellar: Plus Vietnamese continuity person, Vietnamese editor. At every level we had people watching and scrutinizing. [Xuande] did speak some Vietnamese, but not a lot …

Finnie: What would be success for both of you, for this show?

Nguyen: I’m sure from HBO’s point of view it has to be about metrics, of course. For me it was a triumph already just to get the show made. We somehow persuaded HBO to put up as much money as it did to make this show, and now it’s out there. And now you have a show that, I think we’re around a 90% Vietnamese cast, speaking a lot of Vietnamese words, talking about one Vietnamese perspective. That’s really important to emphasize. There will be some Vietnamese people who disagree with the show, and they should, because how can one story tell all of this diversity of Vietnamese points of view. But the point is, my version of success would be that this show is a lever and that it opens further opportunities for more Asian and Vietnamese actors and storytellers in front of the camera, behind the camera to tell even further stories.

McKellar: The show is also about how ideologies sort of calcify and end up alienating people, even though they have noble aspirations at the beginning. And I feel if the show can create a discussion among people and sort of break down some of those boundaries, allow people to empathize across these received separations, maybe it’s a bit of a vague triumph, but I feel like if it can create that kind of discussion, allow people to imagine themselves on the other side of war, recognize another story there that is just as valid — I think that that kind of response is really what I dream for, both within the Vietnamese community and certainly outside it too. … Hopefully for the current wars happening now we don’t have to wait 50 years before we start imagining the other side.

Finnie: Viet, you’ve spoken a lot about historical context and trauma and “Is it history or is it trauma?” And you’ve also spoken very publicly about your mom and her experiences. What do you think she would view of this show and what she would think about it?

Nguyen: I’m reminded of the fact that when I won the Pulitzer Prize, for example, I didn’t actually tell my parents. Because I was like, “Oh, this is what I was supposed to do, right? The Asian kid or whatever.

McKellar: Sorry, but that’s so different from me. My parents would have told me that I’d won.

Nguyen: I’m on the road after the announcement, my dad calls me and, his voice is shaking with happiness. And he says, “The villagers in Vietnam called. You won the Pulitzer Prize.” And I was like, “Oh, all I had to do was win the Pulitzer Prize.” It’s that same thing. I don’t think he ever read the novel. My parents sacrificed so much, now I’m going to make them read my work? But he takes great satisfaction from my my sales figures and my awards. So I think with the TV show, the same thing, I don’t know if they would want to watch it or if they could watch it. I think it would reawaken certain kinds of difficult memories for them, as it has for certain Vietnamese spectators of this show. But I think they would be enormously proud of the spectacle of the show itself. One version of our story is finally getting told on one of the biggest stages available to us as Vietnamese refugees, Vietnamese Americans, Vietnamese people. I think she would have been proud.

McKellar: Now we better win more awards for his parents.