When the Police touched down in Montserrat to record their last album, Synchronicity, there was a sense of finality in the air. Sting, Stewart Copeland, and Andy Summers were restless, prone to quarreling when the instruments came out. Even worse, they could barely make progress on new songs. So Summers hatched a fairly cheeky plan: He would ask famed Beatles producer George Martin to talk some sense into them. (It helped that Martin owned the studio they were recording at.) “We got to a point where it was difficult for the three of us to be in the same room together,” Summers said. “I thought, Of course he’s going to help us. What a shot for Sir George! I had to fight my way through all the tropical foliage of the valley on this little dirt path to get to his house. It was like Tarzan hacking his way through the jungle.” Over a cup of tea, Martin embraced the role of a rock admiral. “He knew how to guide things,” Summers recalled. “I said, ‘We’re not getting along very well or able to put things together. We need assistance.’ He gave me some comforting advice and said, ‘You’ve got it in you. Go back, and I think it’s all going to work.’”

Amazingly, it did. When Summers returned to the studio the following day, it was as if Martin “waved his magic wand over the whole situation.” Sting was laying down some bass grooves. Copeland was minding his business on the drums. Summers had the time to hone new guitar licks. Maybe they could finally bang out another hit? “Suddenly we were very polite with one another and accommodating. We went from one end of the spectrum to the other,” he explained. “We worked it all out and we didn’t have much of a problem after that.” Every bond, move, and step the trio took from then on led them to creating one of the most commercially successful lead singles of all time: “Every Breath You Take.” “I recently saw that it hit 2 billion streams on Spotify,” Summers, about to embark on a summer solo tour, added. “I was just about to write to the accountant in London and go, ‘Should we talk about this?’ Because even if it’s half a dime for every play, it’s got to be a lot of money.”

“Roxanne,” Outlandos d’Amour (1978)

The Song

We went to play in Paris and had no money whatsoever. The three of us ended up in some very dodgy youth hostel. Sting and I had to sleep in one bed together, and Stewart grabbed the other one, because that’s typical Stewart. We were going to do a show, but no one had told us the gig was canceled. The names were on the door, but the place was locked up. It was terrible. We were penniless. We had nothing to survive with. So that was depressing. I learned that night that Sting wandered off to that area in the city where they still had the coral on the street and there were a lot of street walkers. You’d see people lined up around the block to go into a brothel. That was the reality in those days.

We decided to get back to London as soon as possible. Sting stayed with me and my wife in our flat. One night, we heard him strumming and singing a song. The lyrics became “Roxanne.” The first time I heard it, I thought, Oh yeah. My wife turned to me in bed and said, “That’s really good.” And I went, “Yeah, but it’s a Brazilian bossa nova. What is he thinking?”

We went back to rehearsing because no one would give us a gig anywhere. We’re practicing in a gay hairdresser’s flat in North London. He had a basement, which was full of wet cement and concrete. I remember it clearly. We were trying to come up with punk songs because it’s what we were doing at the time. We’re flailing around. Stewart said, “Why don’t you do that ‘Roxanne’ thing?” Sting was still playing it like a bossa nova and it wasn’t the mood of London in those days. So we started working on it. Stewart said, “We can’t do it like that. It’s got to be rock. We can put the bass drum in that. Okay, that sounds kind of pretty.” I start playing, “Bap, bap, bap bap bap,” which counteracts with the kick drum and is easy for the bass to play. That’s how we turned it into the rock sound that became the famous song.

The Bet

The prevailing punk atmosphere at the time was so strong that you couldn’t play a ballad. We were recording at this little studio called Surrey Sound and still poverty-stricken. They would let us play there for nothing. Miles Copeland, Stewart’s brother, would pop in sometimes. He wasn’t even managing us. He hated us, really. I think he hated me in particular. We sat down on the couch on this one night and played what we accomplished so far. We were really scared to play him “Roxanne.” But at the end, we played it. Miles stood up and went, “That’s the one.” We were absolutely shocked. We thought there was no way he was going to like it. He took it to A&M and they gave us a record deal.

The Payoff

It was kind of a flop. The only thing that came out of it was one journalist wrote, “Watch this band. This is a bit special. These guys have got something.” That was all. It wasn’t a hit, but it had a double life. We released it a year later when we were starting to get some profile, and it went to No. 1. And now it’s one of the immortal songs of all time.

Before that, A&M got to know us and realized we weren’t complete knobs. They said, “All right, it didn’t quite work. We’ll give you another shot. Have you got anything else?” So the next single was “Can’t Stand Losing You.” We had a semi hit with that, but we were still struggling. No one would give us gigs. We were sort of a suspect band. The last-ditch attempt to stay together was to fly to America and play at CBGBs. It was a dump, but everybody wanted to play there. We only had six songs. The place was half-filled and no one knew who we were, but we were absolutely thrilled with the reception we got. That’s when we thought, basically, Fuck London, this is the place. From then on, we did a great little tour of the East Coast. In Boston, there’s a guy called Oedipus — he was a very popular DJ. He was playing “Roxanne” around the clock. He was the guy that set it on fire.

But when we went back to London, there was nothing else and no opportunities. We had to break up again. But Stewart’s brother came through and said, “There’s an opening gig available.” There was a comedy pop band called Alberto y Lost Trios Paranoias. It was about 50 shows and they were going to tour all over Britain. We said we’re grateful for anything. So we drove down to our first gig at the University of Bath. It turned out this hall held about a thousand people, and it was a thousand punks going mad. We were thinking, Jesus, the Albertos are so hip. Look at this audience. No, they were there for us. They were jumping, pogo-ing, and thrashing up against the stage. The girls were screaming. Man, we were on fire. The Albertos were standing at the side of the stage with white faces. What have we unleashed? We had arrived. From then on, we started the great ascent.

“Message in a Bottle,” Reggatta de Blanc (1979)

The Song

We were back at Surrey Sound. The band was still getting to know one another, although we got along quite well. Everything was very tentative, like, “Hey, man, you play this.” Typical musician talk. Sting is quite inward. He wouldn’t share much about his songs, but he suddenly popped out with these chords and went, “Well, I’ve got this one about a castaway searching for connection. I’ll show it to you.” Slowly the melody and the lyrics emerged. I thought, Christ, this is a great song. I loved the structure — it’s not necessarily standard with the way the verses flow out. For me it was the best drum tracks Stewart ever laid down. And Sting has no problem singing harmony with himself. He’s totally got the ears and voice for it.

The Bet

We did “Message in a Bottle” and felt triumphant. Another part of the equation was that A&M was starting to smell something. Basically the guys in record companies don’t know shit about music. Sorry. That’s the grim truth. Two guys came down and in our naive stage, we viewed them as higher-ups, like they’re officers of the company, when in reality they were just two chaps who had jobs there. They sat on the couch and we said, “Well, we’ve got this one that we just finished. We like it.” It was “Message in a Bottle.” When we played that, they sat there with huge grins on their faces, because they got it in one. They knew it was going to be a gigantic worldwide hit.

The Payoff

With “Roxanne” and “Message in a Bottle,” we distinguished ourselves as being superior, musically, to almost every other band. We weren’t a punk band. We found a very definite style. It was both rough and polished, in the very general sense. Stewart had a very distinctive drum style. I had so much on the guitar because I had been playing a bit longer than them. And Sting is a naturally great musician. We both loved Brazilian music and grew up with jazz. We came from a similar background, which was almost anything but just straight-ahead pop music. We had all this stuff we could swap together and had a very strong musical partnership. We knew what each other was talking about. And then Stewart was this offsetting drummer that counteracted these tendencies. We used to joke that if Sting and I were left around, we’d probably be an orchestra or classical band. So it wasn’t a normal rock band. The chemistry between us was so strong.

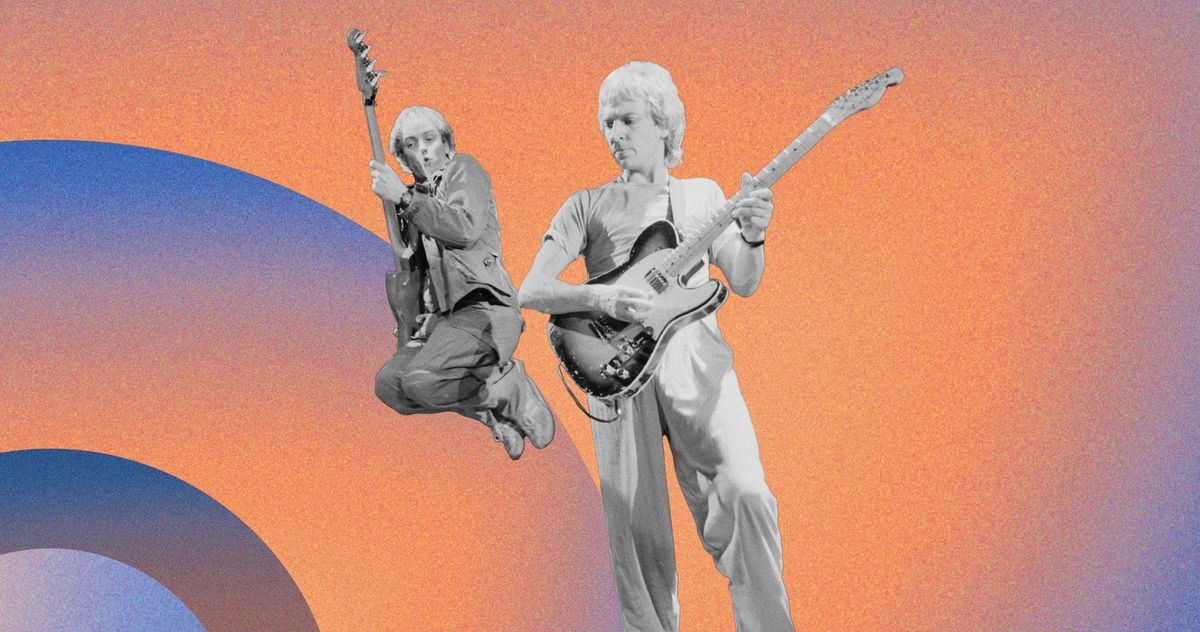

We were cute guys. We were nice looking guys. Everybody went mad because we were completely sellable as a pop unit. If the three of us were together and we turned up anywhere, a huge crowd would appear. It was one of those moments, and we were at the forefront of it. We weren’t exactly a boy band, but we had tremendous adulation and appeared to the female section of the audience, to put it politely. They wanted to be with us, talk to us, and give us their money.

“Don’t Stand So Close to Me,” Zenyatta Mondatta (1980)

The Song

We were very literate and college educated. We were all voracious readers. The lyrics for this comes from one of the first lines of Lolita. Sting had a short spell as a schoolteacher in his early years when he was trying to get started as a full-time musician. So he came up with this song along the Lolita narrative, which is a relationship between a teenage girl and a teacher that wouldn’t have been that much older. There were sort of temptations there and lines that shouldn’t have been crossed. It’s not pushing anything too much, but it had a catchy chorus. The guitar lick was sort of a ripoff of Buffalo Springfield’s “For What It’s Worth.” I’ll admit it’s not really original. One of the distinctive things is the guitar solo in the middle, where I used the brand-new Roland guitar synthesizer that had just come out, which has got this sound of a jet flying overhead. Stewart liked to frequently point out, “You press this button and it goes, Whoosh. You press that one, Whoosh.”

The Bet

We talked about it, and that was a clear winner. It was a strong pop song with a big, hooky structure. At this point we were so popular that it almost didn’t matter what we put out — it would’ve been a hit.

The Payoff

We really got going in 1979, but in 1980, we were without question the hottest band in the world. But cracking America took three whole tours. We worked very hard in the U.S., state to state, show to show. Gradually, the shows got bigger and bigger. We were the kings in the U.K., and our manager had us touring America. I remember we played in a little dump somewhere in the Carolinas because the watch word was, “You must break America.” So we were No. 1 in the U.K. with a million singles sold of “Don’t Stand So Close to Me.” Everybody was going mad for us. And we were playing in a boathouse somewhere in the Carolinas, because we were supposed to be on tour in America. It was ridiculous irony and probably terrible management, but that’s what we were doing. It eventually panned out.

“Invisible Sun,” Ghost in the Machine (1981)

The Song

We’re serious people. I’m certainly one who goes to the dark side. Dark music is better than light music — that’s my statement. This was a song that had a nice little guitar riff and atmosphere. I wanted to keep synthesizers out of the band altogether, because we were great guitarists. We don’t want a bloody synthesizer. The song was about the Troubles in Northern Ireland and what it was like to be an Irish person there. It was the spiritual idea that there’s an “invisible sun.” There’s something you can hang on to, if you like, despite the surrounding problems. It worked as a pop song because it had a strong melody with a hook.

The Bet

There was a significant disagreement about Ghost in the Machine. A song that I wrote, “Omegaman,” should have been the lead single. That’s what A&M wanted. Now you get into the politics of the band. By this time, Sting was pulling us out because he was the main songwriter and believed no one else could ever do it. He got really snitty about it, put his foot down, and said whatever he said to change the lead single: “I’m not going to be in the band, blah, blah, blah.” He made a big deal out of it. So instead of “Omegaman” being the lead single, it got switched to “Invisible Sun.” My song never got released as a single. I think it would’ve been a huge hit. It was disappointing because I was pleased with it. I did a great guitar break in the middle.

I can comment very broadly that being in a band is difficult. People always write about the Police and go, “Oh, they hated each other’s guts.” No, we didn’t. There was a lot of humor and a lot of fun. When you’re in a band, especially when you’re young and on the road, you’re like a gang. You go around and develop codes and tribal words, because that’s who you are. People simplify it. Like, “Oh, they hated each other. They slammed their doors shut at night and hurled obscenities.” They weren’t there. They don’t know what they’re talking about. So yeah, it was disappointing about “Omegaman,” but we moved on.

The Payoff

It was very controversial. The major television show in England that you had to get on to be successful was Top of the Pops. Because the song was about the Troubles in Northern Ireland and politically focused, they wouldn’t play it. It was problematic. People didn’t go, “Oh, thank God. You’ve written a song about the Troubles. You’ve brought it to the surface.” Right now, I suppose the equivalent would be if you wrote a pop song about the Gaza Strip. You’re going into a difficult area. Certainly at that time, it was Northern Ireland with more problems. It had what we call a checkered career. The music video that went with it showed people in Northern Ireland on the streets and some of that violence. We dealt with Auntie BBC and they wouldn’t play the video, either. The world has changed, not for the better.

“Every Breath You Take,” Synchronicity (1983)

The Song

Sting had had it at this point. One day he was like, “We’ve done what we signed up for. Five albums. That’s it. The job’s done.” He wanted out and to be on his own. He’s a pretty introverted guy who’s also a control freak. It was difficult to get through that album, which of course became this gigantic seller that went straight to No. 1. Why did it go to No. 1? Because I wrote the guitar line for “Every Breath You Take,” which transformed it. We had the songs and were working away at stuff, but there was a grudging and difficult atmosphere. Sting had been working on “Every Breath You Take,” and all of his demos had a huge amount of keyboards on them. It was absolutely a non-Police song, because the Police sound was defined by the guitar. This demo had these shrieking, big synthesizer parts on it. It was awful.

We said, “We have to make it our own. It’s got to sound like us.” Stewart and Sting were arguing for weeks about this, because the song had been sitting around and nothing would work. They were fighting about where the kick drum and the bass should go. I was just waiting. “Did you guys sort this bloody thing out?” Finally, one day after a huge lunch, Sting said, “Go on, go in there and make it your own.” I went in and the famous guitar line came to me very quickly. They were all watching through the window at me standing alone in the studio. When I finished the guitar line all in one go, they all stood up and cheered. It sealed it.

The Bet

Miles came into the studio and said, “I want to take that to the radio now. That’s going to go to No. 1.” We didn’t even wait for the album to come out. That was indeed our first No. 1 song in America.

The Payoff

It went straight to No. 1 in nearly every country. We were bigger than the world at that point. The thing about “Every Breath You Take” is that it has a very haunting guitar line and a dynamic bridge. It was all there. A lot of songs are very worthy, but I think this one cut through because of its simplicity.

More From The Song Roulette Series