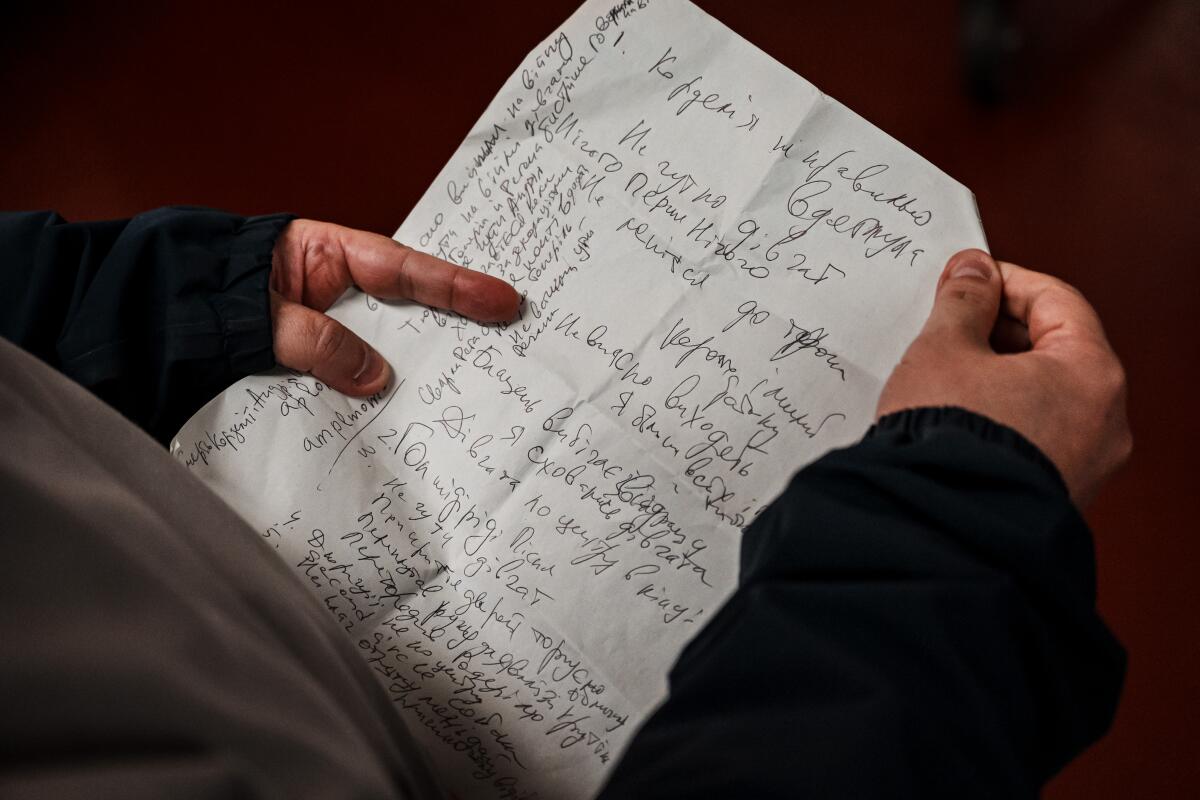

The stage set was haunting in its stark simplicity. Panels of jagged crossbeams evoked skeletal ruins. Lengths of white fabric fluttered like shrouds.

For almost any theater troupe in the world, it would be daunting to stage a Shakespeare production in Stratford-upon-Avon — the Bard’s birthplace, home of the venerable Royal Shakespeare Company, hallowed ground to devotees of the playwright and his works.

All the more so if the players in question were amateur actors. Even more if the play happened to be “King Lear” — one of Shakespeare’s greatest tragedies, and also one of the thorniest and most challenging.

And finally: if the performance was entirely in Ukrainian. Without subtitles.

That’s the task a provincial Ukrainian theater company set for itself — a wartime feat that sprang from luck and determination, warm collaboration and cool nerves, taxing logistics and small, hard-won triumphs over trauma.

Outside, a soft rain fell. Inside, a storm raged. On a stylized heath, the mad king howled his wounded howl.

“Blow, winds!” shouted actor Andrii Khomik, as Lear. “Rage, blow!”

The amplified thunder roared. The stage all but shook. The audience sat rapt.

1

2

3

1. Ahnesa Tsvilodub performs as Regan during a rehearsal of “King Lear” at the Other Place theater in Stratford-upon-Avon, England, on June 14, 2024. 2. Andrii Khomik as King Lear and Olena Aliabieva as the Fool perform onstage. 3. Andrii Khomik, center, conjures a formidable but vulnerable king. The former museum worker and his family fled Crimea for western Ukraine after the peninsula was illegally annexed by Russia in 2014, an act that most Ukrainians consider the true start of this war.

Twenty-four hours earlier, on the eve of Saturday night’s performance, director Viacheslav Yehorov, 51, stared down at his tightly clasped hands.

Exile and loss, battle and betrayal, disinheritance and vengeance, old age and human frailty — of all the grandeur and pathos of “King Lear,” one theme had always stood out for him.

“That without love,” he said, “we are nothing.”

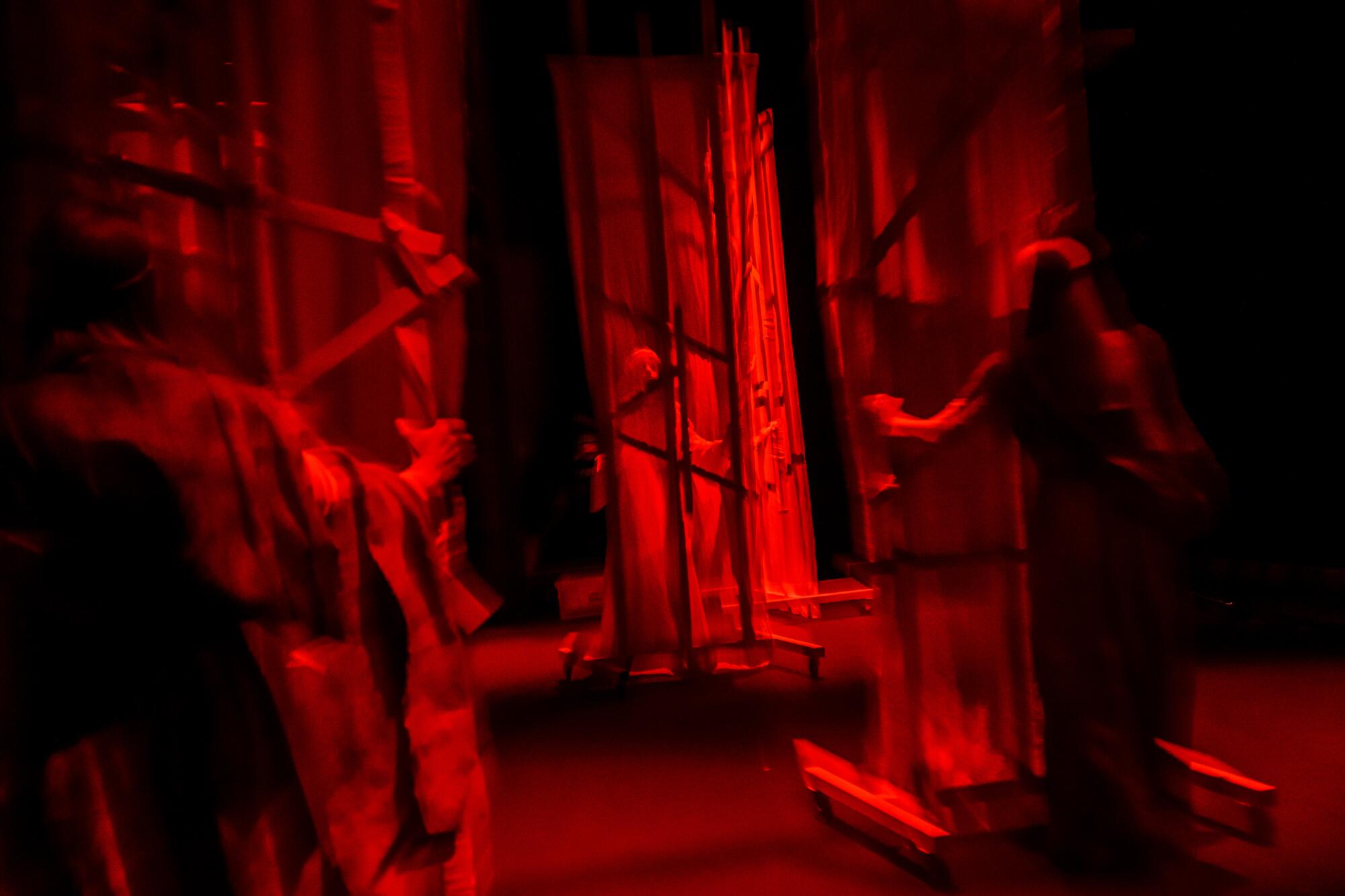

— King Lear, Act III of “King Lear,” by William Shakespeare

Uzhorod, the troupe’s Ukrainian home city, lies in the shadow of the Carpathian Mountains, close by the border with Hungary. Today, that frontier with the European Union is a dividing line between war and peace.

After Russia’s full-scale invasion in February 2022, the small city in Ukraine’s far west, home then to about 120,000 people, swelled to triple or quadruple its former size. Every day, from front-line towns and cities across the country, trains disgorged throngs of desperate people seeking safe haven.

“It was very difficult at first,” said 23-year-old Myroslava Koshtura, who shares a rotating role as the king’s faithful youngest daughter, Cordelia. She, her two brothers and their parents — plus two dogs and a cat — initially lived in a single room in Uzhorod after they fled their home in the bomb-pummeled southern port city of Odesa.

For the city’s newly displaced, life settled into a daily round of picking through donated clothing, volunteering in soup kitchens or weaving camouflage nets, scrolling through messaging apps for word from faraway loved ones.

The war, now in its third year, was only months old when, one by one, Koshtura and others spotted fliers posted by Yehorov, who worked in children’s art therapy at a local film school: Actors wanted. No experience needed.

1

2

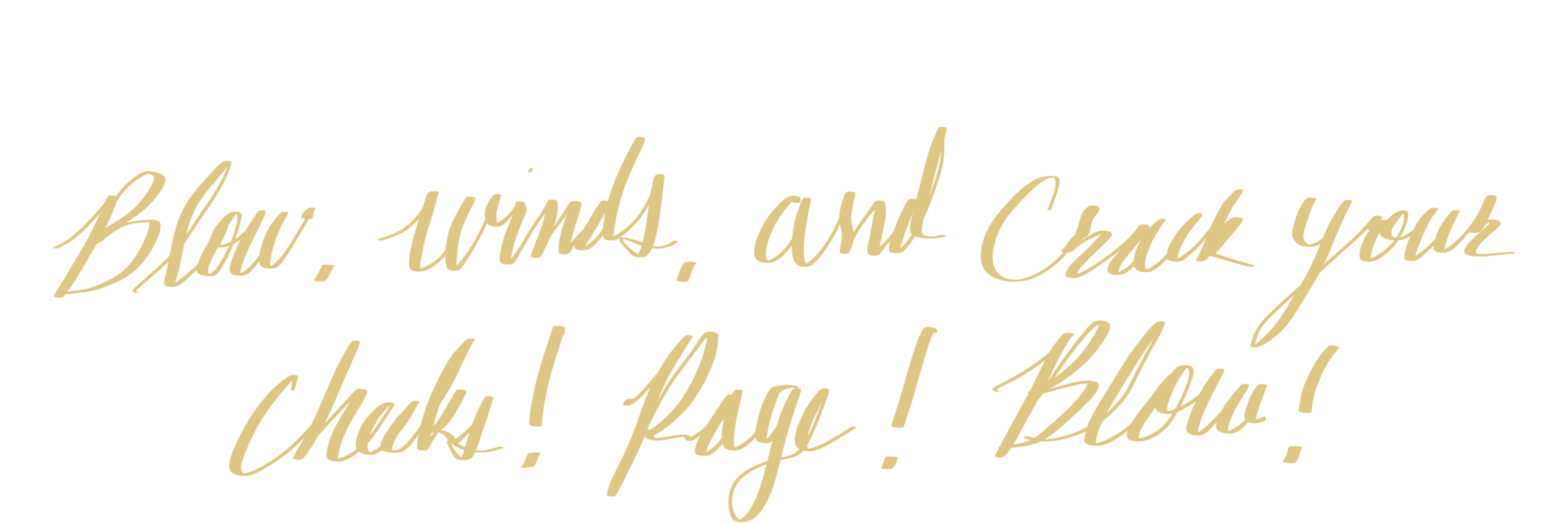

1. Viacheslav Yehorov gives the cast directorial notes in the dressing room during a break between rehearsals of “King Lear.” 2. Yehorov holds his notes.

“I thought: Could I do this?” said Olena Aliabieva, 38, a visual artist from the devastated northeastern city of Kharkiv. She could: She plays the Fool — usually a male role — the court jester whose comic antics soften the sting of bracingly honest commentary. Through the character’s eyes, the audience sees Lear’s catastrophic error in trusting his flattery-dispensing elder daughters rather than the youngest, who truly loves him.

Yehorov — portly, rumpled, intense — wasn’t looking for professional polish. Instead, he asked would-be players to tell him their war stories. And they did: sons or fathers dead on the battlefield, obliterated hometowns, old lives left irretrievably behind.

Ahnesa Tsvilodub checks on Andrii Khomik, who felt a cough coming on and huddled under a blanket for part of the day before he would perform as Lear.

“I felt that these people were already actors in a real tragedy,” he said.

Some of those who joined in this odd new theatrical endeavor — doctors, laborers, lawyers, accountants — had never read Shakespeare. None had imagined themselves taking to the stage.

“For 20 years, I worked in a museum,” said Khomik, 65, whose white beard and regal bearing conjure a formidable but vulnerable king. As does the exile he has known; he and his family fled Crimea for western Ukraine after the peninsula was illegally annexed by Russia in 2014, an act that most Ukrainians consider the true start of this war.

Soon enough, as the company coalesced, a paradox developed: The amateur actors came to see performing as a therapeutic balm — even if the play’s turbulent content sometimes summoned up their own sadness and fear.

For some, depression lifted: Painter Aliabieva, who had previously worked in black and white, found herself drawn to use of vibrant color in her visual compositions.

Myroslava Koshtura, center, and the rest of the cast perform a sword-fighting scene by moving props of metal and gauzy fabric.

But resilience can be fragile. After arriving in Stratford-upon-Avon, the cast had an outing to “The Merry Wives of Windsor,” currently in the Royal Shakespeare repertoire. But the sound of simulated gunshots unnerved one of the Ukrainians so badly that she had to leave the performance.

“Even if we seem fine, sitting here, we all have triggers that affect us,” Yehorov said.

At the heart of the theatrical endeavor, though, is a spirit of defiance in the face of a war that has taken so much from so many.

Watching white swans transverse the tranquil river in front of the theater, Khomik said his portrayal of Lear was meant to convey not only suffering, but also a sense of fortitude.

“What we hope is that people will understand our soul,” he said.

1

2

1. Veronika Hromadska helps Olena Aliabieva put on her makeup as the Fool in “King Lear.” 2. Ahnesa Tsvilodub makes up Andrii Khomik before he goes onstage as King Lear.

More than a year after the Russian invasion, a British humanitarian aid worker who traveled often to Ukraine returned to his Stratford base, bearing — with a measure of Shakespearean brio — extraordinary tidings.

He told a contact at the Royal Shakespeare Company, or RSC, about a theater troupe made up of war-displaced amateur actors staging well-received performances of “King Lear” — but so far, only in Ukraine.

To Zoe Donegan, the RSC’s head of producing, the notion of forging some sort of partnership with the Ukrainian troupe was irresistible.

“I suppose it resonated because of the way that even at times of extreme stress and extreme fear, people turn to Shakespeare, to theater, to these words that were written four hundred years ago,” she said.

With the assent of the RSC’s senior leadership, talks began.

“We were stunned,” Yehorov said of the British overture. “It was like a dream, a fairy tale.”

But the work had only begun. Over the months, as the war ebbed and flowed, the Uzhorod troupe and RSC representatives held regular Zoom meetings, brainstorming ways to bring the production to Stratford-upon-Avon.

Olena Perekotiienko, right, and other cast and crew listen to director Viacheslav Yehorov in the dressing room between rehearsals.

They initially set a target date at the start of this year and couldn’t quite make it work. But no one wanted to walk away from the idea, however quixotic it sometimes seemed.

They wrestled with the question of whether to stage the play with subtitles, deciding not to in the end. Both the Ukrainian company and their British hosts believed that theatergoers familiar with the play — and even those who weren’t — would be able to not only follow along, but to also engage emotionally with the actors.

“To add subtitles would change the experience,” Donegan said. “I think it’s a universal language.”

The play and players, meanwhile, were gaining fame and traction. They were featured in a Ukrainian-produced documentary, “King Lear: How We Looked for Love During the War,” which had its international premiere in May 2023 in Los Angeles.

This spring, Donegan was able to procure permission for 15 members of the rotating cast and crew to come to Britain. The Ukrainian visa recipients had to travel to Kyiv, the capital, to claim them in person, a 500-mile journey through a wartime landscape.

And special permission was needed for Yehorov to leave the country; Ukrainian men in their 50s are still considered to be of military age, and only rarely allowed to depart. (At 65, Khomik was exempt; a previous, younger Lear was not.)

1

2

3

1. Ukrainian cast members put their fists together in a circle to form a crown. 2. The cast members embrace in a warm-up circle. 3. A group back rub is part of the warm-up for the displaced Ukrainians.

Because most men were fighting, the play had already been adapted in female-centric fashion, with four of the five speaking parts played by women, and most male roles eliminated, save for the king.

On June 10, when the troupe was finally ready to travel to the Hungarian frontier, the RSC team anxiously tracked the Ukrainians’ progress from 1,500 miles away.

At last, word came: They were safely out — all of them. Donegan and her colleagues cheered.

From Hungary, the Ukrainians flew to Luton airport, outside London. By that evening, they were in Stratford-upon-Avon.

The white swans glided. The stage lights beckoned.

From its earliest stagings — scholars date the first to a performance at King James’ court in 1606 — “Lear” was considered famously difficult. Over the years, some of Britain’s most storied actors have balked at taking on the role.

Even theatrical giant Ian McKellen, in the telling of the Guardian newspaper, asked plaintively in 2005, “I don’t have to do Lear, do I? Everybody expects me to.” Soon after, he agreed to play the part for the RSC.

Lear lore abounds. There have been female kings, stagings in innumerable languages, productions set in Viking times, or in a modern-day nursing home with Lear’s madness depicted as a senescent dream.

During the reign of Britain’s King George III, who suffered bouts of mental illness, the play was thought to cut too close to the bone. A decade-long ban on performances ended only after his death in 1820.

The cast first appears onstage in close-fitting long johns, retrieving outer costumes from big silver trunks — recalling the hurried flight of the war-displaced with little more than the clothes on their backs.

Other key characters and scenes came and went: For a century and a half, beginning in 1681, the crucial role of the truth-telling Fool was excised, and Victorian theatergoers were spared the awful spectacle of Gloucester’s blinding.

Over the centuries, as Shakespeare’s reach extended worldwide, Ukraine, under the sway of the Russian Empire, entered its own fraught relationship with the playwright and his works. For a time in the 1800s, Ukrainian-language translations and staging of Shakespeare’s works were forbidden by Russian overlords.

Since the 2022 invasion, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky has sometimes turned to Shakespeare to rally his compatriots — and to try to convey to the outside world the existential nature of the threat.

In a virtual address to British lawmakers soon after the war’s outbreak, Zelensky quoted “Hamlet,” with its best-known line, so often reduced to modern cliche, now laced with urgent peril.

“To be, or not to be?” he asked.

Showtime. At last.

After a final round of rehearsals, and a special performance staged for invited members of the Ukrainian community in and near Stratford — ranks swelled by refugees — the company was ready to take the stage on for its short public run: a single matinee, followed by an evening performance.

In the 232-seat theater, one of the RSC’s smaller venues, cramped backstage quarters spoke of intimate bonds. The cast enacted its pre-performance rituals: a circle of determinedly clenched fists, neck rubs dispensed and received, plenty of fussing with one another’s hair.

The hours before had been a mix of tension and giddiness. Lear felt a cough coming on, and spent part of the day huddled under a blanket on a backstage couch. One of the Cordelias was missing her boyfriend.

Yehorov, pulling a sheaf of stage notes from his pocket, dropped a container of toothpicks that hit the floor and scattered everywhere. The cast burst out laughing.

Soon enough, though, the mood turned edgy and somber.

War may be universal, but the play’s opening moments carried unmistakable allusions to the conflict in Ukraine. The sound of a piping flute — a familiar hallmark of Shakespeare productions — gave way to the shriek of train whistles, the thud of pistons, and Ukrainian-language announcements of trains arriving from battered cities across the country.

The cast made its first appearance in close-fitting long johns, solemnly retrieving outer costumes from big silver trunks — a gesture that recalled the hurried flight of so many war-displaced with little more than the clothes on their backs.

1

2

1. Ahnesa Tsvilodub hugs Myroslava Koshtura, holding flowers, after their performance in Stratford-upon-Avon, England. 2. Members of the audience listen to director Viacheslav Yehorov, right, give a toast to his cast and crew.

Then the players plunged into Shakespeare’s oft-told story, in their own telling, and their own way.

The supercilious elder sisters preened. The Fool capered and unleashed unrelenting verities. The battle scenes were abstract but chilling: smoke and blood-red light, the grinding clash of metal on metal.

When it ended, the audience rose to its feet, applauding.

The stage floor was illuminated with the colors of the Ukrainian flag. Yehorov and the actors looked happy, and spent.

The players accepted bouquets and posed for pictures. Cast and crew repaired to an 18th century pub a few doors down, where thespians traditionally raise a raucous toast to a play’s successful run.

In the morning, the company packed up and left Stratford-upon-Avon; after a stint of London sightseeing, its members headed home. Home to the war.

On the performance’s eve, the youngest cast member, Koshtura, said she sometimes thought about how and when the fighting might end.

“Life will go on, but it won’t be the same,” she said. “We are different now. Everything has changed.”

It’s possible, these players have come to believe, to imagine an aftermath. But in life as in “Lear,” there are times when there is no going back.

Myroslava Kohstura, center, speaks to Andrii Khomik, right during an after-party. Soon the Ukrainian troupe would return home to the war.

Read more coverage of the war on Ukraine.