One afternoon nearly 20 years ago, a lawyer named John Robert Nelson began to lead a double life. He was 37, working for a small firm in a small town on the coast of Northern California and earning so little that he had to get up at three every morning to deliver newspapers. The alter ego he created led a more glamorous existence. “Enty Lawyer,” as that persona was known, was the author of Crazy Days and Nights, a Hollywood-gossip blog that would go on to acquire cult status among devotees of celebrity dirt. In his first post, Nelson wrote that he’d started the blog because he was in a “unique position of being able to tell you what really goes on behind the scenes and what even the gossip magazines can’t find out.” In the short biography he posted on the site, he claimed he had represented big stars going through “arrests, divorces, breakups and hookups, new deals and cancellations.” He promised to dish about his clients as well as his own Hollywood adventures with the celebs and pseudo-celebs who populated his life. If his claims were to be believed, Enty was among the most connected guys in Hollywood. He was friends with Leonardo DiCaprio. He drank with Frank Sinatra. He’d picked up Katherine Heigl on the side of the highway at three in the morning when she ran out of gas and collected Quentin Tarantino off a bender in Krakow. A disclaimer said the site published “conjecture and fiction” in addition to “accurately reported information.” It did not specify which anecdotes were which.

It was a good time to launch a gossip blog. By the mid-aughts, the public had grown weary of the fawning celebrity coverage that mainstream entertainment outlets had been offering up for decades. Magazines often worked in collaboration with publicists to present ennobling portraits of the stars and the industry that made them, glossing over drug addictions and infidelities, sexual harassment and corruption. Meanwhile, a new cohort of gossip bloggers like Elaine Lui and Perez Hilton seemed to be stripping away the façade, and they were attracting huge

followings on the internet. Enty was never as big as they were, in part because he wrote anonymously. But he offered something they didn’t. Writing in a unique style, hard-boiled and absurd, he trafficked primarily in blind items, entries written as puzzles that could each theoretically apply to at least two different celebrities — a clever way to both evade potential libel lawsuits and engage readers, who would guess the identities of the stories’ subjects in the comments section. This allowed him to be more salacious than Hilton or Lui. In 2016, a glowing Vanity Fair write-up declared him “the King of the Blind Item,” claiming Enty had become “a direct source for gossip that evades the normal channels of celebrity news and feeds directly into the Internet’s never-ending appetite for the juice.” What made him the king, according to Vanity Fair, was that unlike other gossip bloggers who might occasionally write a blind item, Enty revealed the identities of his subjects, albeit sometimes years later.

Enty’s Hollywood was a dark and messy world, uglier and more menacing than the glamorous town imagined by outsiders. The authenticity of this vision — and, in turn, the authenticity of his scoops — was bolstered by how pathetic he came across in his own accounts. Enty described himself as a 300-pound heavy-drinking entertainment lawyer who had been married six times, lived in his parents’ basement in L.A., and was bullied by his famous clientele — a zhlub with the right connections and a nose for dirt.

In reality, Nelson didn’t live in his parents’ basement, and he hasn’t been married six times — only three. Today, he and his wife, Victoria, live in Indio, California, a desert city near Palm Springs. Until recently, Nelson told me, the people who knew he wrote the blog included his wife, his brother, a couple of friends and acquaintances, and a handful of celebrities he’d known for years. Then this past fall, his identity was revealed in an unusual legal dispute. He’d had an affair with a woman named Cassandra Crose, whom he met through his podcast, which he’d started in 2018. A fan and aspiring podcaster herself, Crose became his collaborator, then his lover. He told her he was single and wanted to marry her; when she discovered that he was already married and he stopped returning her calls, she threatened to tell the world who he was. Eventually, he pursued a restraining order against her, a decision that had unintended consequences. First, Crose followed through on her threat, creating a podcast of her own in which she narrated the story of their relationship in harrowing detail. On her Patreon, where she posted sadomasochist texts he’d sent her, she framed him as an abuser who’d tormented, deceived, and humiliated her. Internet sleuths, and eventually a reporter for the Daily Beast, dug up the court documents he’d filed and confirmed that Nelson was in fact Enty Lawyer. And so the gossip blogger became the gossip.

His mother, who’d never known about his alter ego, began getting phone calls from reporters; people on the internet called him an abuser and a grifter. Now he was looking into filing a defamation lawsuit on top of the restraining order. He’d submitted thousands of text messages saved on his phone and computer to the FBI’s Internet Crime Complaint Center. And, for the first time in his career, he agreed to sit down with a reporter in person.

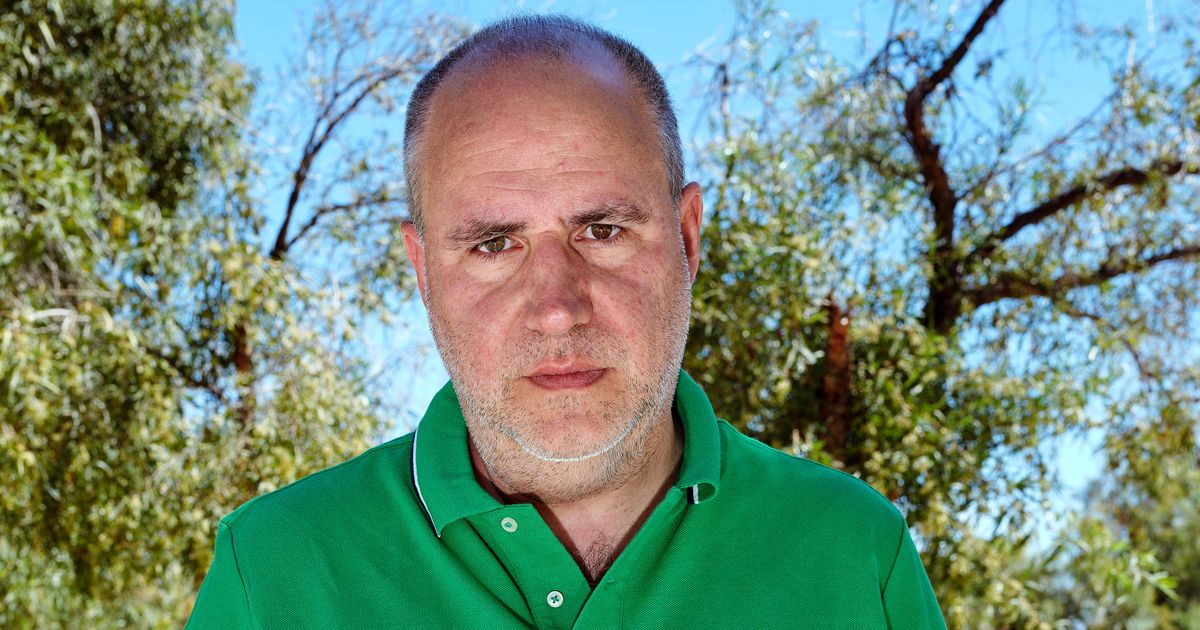

Nelson proposed we meet on a Tuesday in February by some rose bushes at a park in Palm Desert. He wouldn’t give me his phone number. I wondered if he might bail, but a few minutes after noon, a balding man in a blue checked polo shirt, gray chino shorts, and black flip-flops shuffled up and extended his hand in my direction. Contrary to what he had written in his X bio, he was not 300 pounds or even overweight. Sitting at a picnic table in the shade, he removed his glasses, plain black rectangles, and set them on the table. His manner was mild and digressive; he was given to ending almost every thought with a mumbled “or whatever.” As one acquaintance put it, he has the vibe of “a Florsheim shoe salesman.” That didn’t bother Nelson. People tend to “forget what I look like,” he told me. “I like it like that. I don’t need to be the center of attention.”

It was an ordinary day in the desert, hot and dry. Nelson drank from a bottle of orange Vitamin Water. “I never have abused anybody in my whole life,” he told me. On the contrary, Crose had been abusing him, he said. Nearby, someone was on a lawn mower, cutting grass. Ignoring the noise and dust, Nelson said he doubted the restraining order would stop her from lying about him. “Can I tell you why?” he asked. “Money. Content. The incentive for her is to ratchet it up.” That was something he knew a lot about. “To get new content,” he said, “you’ve just got to start making up stuff.”

Nelson says he grew up in Washington, D.C., the son of two government workers. His parents split up when he was 8. He was reluctant to tell me much about his family (and the details he did share are impossible to corroborate). The only memory he recounted of his parents was of them fighting before they got divorced. “I would wake up to them screaming at each other,” he said. His mother was director of the national school-lunch program and later the national director of WIC, the nutrition program for women and children. His father lacked ambition, Nelson said. “He didn’t really care about advancement or anything like that.”

After the divorce, Nelson and his mother moved around. When he was in high school, they lived near Dallas, where Nelson claimed he had his first exposure to show business. He recalled attending a music festival with a friend his junior year of high school; the friend was doing lighting work, and the two ended up backstage. He was fascinated by how different the musicians seemed from their public personae. “You go see this person you’ve admired, and they’re treating some staffer like crap,” he said. A few actors were hanging out with them backstage. “That was the first time that I saw them up close. They looked completely different in real life,” Nelson said. “I’m watching people do all kinds of crazy drugs and injecting stuff.” This, he decided, was what he wanted to do. “I don’t need to be out in front,” he thought. “I like being in the nuts and bolts and seeing what’s going on.”

While attending Texas Lutheran University in the late ’80s, Nelson wrote a column in the student paper under a pseudonym. He pretended to be a rube who had grown up on a farm, a fish out of water perplexed by student life on a busy college campus. Around then, he started working as a freelance concert promoter, but he didn’t earn enough to consistently pay the bills, so after graduating, he got a job at an airline answering phones, then moved to sales. In his early 30s, he applied to the Thomas Jefferson School of Law — a low-ranked establishment that later lost its bar accreditation — because he did not want to risk applying to a place that might reject him. He passed the bar in 2005 and was hired by a firm in Humboldt County, California, handling probate proceedings and business contracts.

Working for a small firm in the middle of nowhere, he was bored and restless. He told me the L.A. “It” girl Cory Kennedy, whom he described as a friend, had recently started a blog, and he thought, “Hey, I can try that. It’s free.” (Kennedy said she doesn’t remember ever meeting him.) Nelson launched the blog in November 2006. While he passed his days in the office, Enty Lawyer supposedly went on a date at the L.A. celebrity haunt the Ivy, ran into The Sopranos star Jamie-Lynn Sigler, and represented an “A-list actress” who “almost got arrested for crack.” (Nelson said that during this time, he was visiting L.A. once a month and staying with friends.)

Six months later, Nelson moved to L.A. He thought he could get back into the music business, maybe manage some musicians. Instead, he took a job at a small firm in Central L.A. where he handled probate law. He told me he had a side hustle as an entertainment attorney and showed me a few emails from 2011 in which he appeared to be representing a small-time producer. (He was known, he said, for being a person who would handle legal matters “for cheap.”) He first met Hollywood people through friends he’d made as a concert promoter, he said, and, later, through his work as a lawyer.

Nelson didn’t try to make money from the blog for the first few years. “It was more about making sure everybody had a good time.” A small community formed around the site. The same people were in the comments every day, and he got to know some of them. He ran a Facebook page as Enty and made a point of wishing every member a happy birthday. He met his third wife, Victoria, through that community. He told me he never fooled himself that the blog was a big deal. When Hilton and other gossip sites posted a production still of Jennifer Aniston topless, they got cease-and-desist notices. Nelson, who had also posted the picture, didn’t, but he took it down anyway and wrote on the blog that he’d received the notice. “I wanted to be part of the group,” he told me. Another gossip writer, Ted Casablanca, who was known as “the King of Blind Items” before he retired in 2012, recalled Nelson reaching out to him around this time. “It’s like he was pulling up to a poker game,” Casablanca said. “He wanted in.”

Fans seemed to buy what Enty was selling. They’d speculate about his sourcing, theorizing at one point that Robert Downey Jr. was dropping tips in the comments. (Downey’s publicist flatly denied this.) But fellow gossip writers were not so easily impressed. Hilton, not exactly a figure known for journalistic scruples, felt that Enty’s standards on the blog frequently fell short. “I think he’s full of shit,” he told me. Another prominent gossip writer doubted his sourcing. “There’s just no way he’s getting that much scandalous information on a daily basis,” they told me. “I get maybe two good blind items a week, and one of them might just be that some TV show will start filming in March.” The writer came to believe Nelson regurgitated most of his items from message boards like Reddit and Lipstick Alley and turned them into blinds. The posts that resonated, they added, usually rang true because they played into ideas that readers already had about any given celebrity. “What he does is very sleight of hand,” the writer said. “He’d write a blind item, and the reader would say, I think I’ve heard this before.”

Take one typical post from 2006, in which Enty described an encounter with an “A list forever” movie star in his 60s who ostensibly spent a week in Enty’s office preparing for litigation. Over the course of the week, Enty claimed to have witnessed excessive drinking, cheating, a party with other aging stars “in various stages of undress” and very young women, and middle-of-the-night “emergency” phone calls summoning Enty to fetch liquor and whatever else the situation required. Eight years later, Enty reposted the item and wrote that the misbehaving star was Sean Connery. Connery had long had a reputation for heavy drinking and womanizing, so it was not inconceivable that he could have behaved that way. But what made the story compelling was that it was presented as a firsthand account, and that aspect was certainly fiction. When the anecdote had supposedly taken place, a couple years before Nelson had written it, Nelson was still in law school. According to public records, he had not yet lived in L.A.

When I brought this up with Nelson, he admitted that he’d never worked for Connery. He said he’d gotten the anecdote secondhand from a law-school friend who’d worked as a gopher at an L.A. firm. (When I asked him to connect me with the friend, he declined.) “Obviously, as a lawyer, I’m very big on the truth,” Nelson told me. He said he never outright made up items but sometimes published tips from readers that he had “no way to verify. The less I believe it, the more obscure and generalized I will make it. But I don’t just randomly make up stuff.” He might fudge an anecdote now and then, but the truth mattered. “The heart of whatever you’re saying needs to be true.”

Enty didn’t always pretend to have witnessed the action with his own eyes. Often, he would publish a tip without any framing. Nelson told me that some of his best tips came from paparazzi and reporters. That may be true. In 2013, he wrote that a superstar had fired an employee after discovering a video of him masturbating to pictures of her and her daughter. When the star learned that a magazine planned to go public with this story, she agreed to pose for the cover in exchange for the piece getting killed. “In the next couple of months when you see a cover and go wtf, now you know why,” Enty wrote. A few months later, Beyoncé showed up on the cover of Shape, a now-defunct fitness magazine. He reposted the blind with Beyoncé’s name attached and published it again eight months later, when the fired employee — Beyoncé’s bodyguard — died in a bizarre break-in in Miami. While the story was never confirmed, major publications reported on the allegations and credited Crazy Days and Nights. Nelson said he had gotten the tip from a writer who was frustrated that the magazine had traded away his big scoop.

Five years in, in 2011, Nelson began to look into ways to profit from the site. Money was tight, and L.A. wasn’t cheap. He ran Google ads and began writing every day from his desk at the firm and at home on the weekends, posting as many as ten items a day, sometimes more. The following spring, he published one of the most viewed entries in the blog’s history, a blind about a “former B list television actress” who he alleged had been physically abused by her father and boyfriends. The post went viral after a frequent commenter who went by “Himmmm” claimed (without proof) that the actress was Hayden Panettiere, the former child star who’d recently been cast in Nashville. The commenter also claimed, outrageously, that her abuse was part of a much larger story and suggested readers take a look at Diana Jenkins, a Bosnian-born socialite, entrepreneur, and ex-wife of an executive at Barclays: “She’s the Rosetta Stone of every scandal and perversion from Hwood all over the globe. She’s been running a high class call girl/party-girl ring for Arabs, Wall Street, DC, Royals, and Hollywood elites.” Panettiere, they added, was her “little pet.” The post got 100 million page views. By the fall of 2012, Nelson had quit his day job and was supplementing income from the site with legal work on the side.

On the heels of that success, Nelson wrote more and more about rumors of sexual transgressions. He told me he had always been a “champion of women” and was primarily motivated by injustice. Years before places like The New Yorker and the New York Times published accounts of the abuses of Harvey Weinstein, Matt Lauer, and Kevin Spacey, Nelson took thinly veiled swipes at them in his blind items. In 2016, for instance, he wrote about a “producer/mogul” who threatened to destroy an actress’s career after she “refused his advances.” When the Weinstein stories blew up, Enty reposted the blind with Weinstein and Saoirse Ronan’s names attached. (Ronan has never been connected with Weinstein in any other reporting.) In a profile of Enty for the Daily Beast, the former sex-and-dating columnist Mandy Stadtmiller called him a whistleblower. “It’s not just about ‘dirty laundry,’” she wrote. “It’s about justice.” It became something of a trope, in that moment of reckoning, to recast gossip writers as unlikely heroes of public-service journalism. The Ringer went so far as to contend that they had become “industry watchdogs.” This argument, though, elided the thread of old-fashioned misogyny that ran through many of Nelson’s posts. He sometimes implied the women who slept with studio bosses were asking for it. As critics of the site have pointed out, Enty was fixated on “yacht girls,” a common euphemism for actresses who engaged in informal high-end prostitution, and wrote extensively about the “hundreds and hundreds and hundreds” of such women who, he absurdly claimed, populated Hollywood (one of his most frequent targets was Meghan Markle).

Me Too was a breakthrough moment for the blog. In 2018, Nelson launched his Patreon and daily podcast. In his spare time, he embarked on a strange side project for a guy who’d always operated from behind a veil of anonymity: He ran for Congress. Nelson, who campaigned as a progressive Bernie Democrat to represent Ventura County, California, told me he had two reasons for embarking on this mission. He was “ticked off about health care” and interested in peering “behind the scenes” of the electoral process. “It’s not that I thought I could win,” he said. According to Federal Election Commission filings, only 12 people contributed to his effort. I spoke with two of them. One had given $400 but struggled to recall anything about his campaign. “I feel like there might have been a Taylor Swift–ticket hookup?” she said. “Am I crazy?” The other donor said she had no memory of meeting Nelson or hearing his name. When I read her the names of the other 11 donors, she realized she knew five of them. They were all mothers of girls at her daughter’s elementary school. Curiously, all of them had given $390. I later texted her to ask if by any chance she recalled getting Taylor Swift tickets around that time. “Yes, that does jog my memory,” she replied. Her daughter had gone to the show with a group of girls from school. “It went as a campaign contribution?” she asked. “Who knew?!” Nelson told me he did offer Taylor Swift tickets to donors. As a former concert promoter, he had ways of getting them for free. But he said he’d raised the money only to pay his campaign manager. (He ended up coming in last in the race with 3.7 percent of the vote.)

Over the next few years, the content of Nelson’s posts and podcasts grew darker, weirder, and more conspiratorial. He wrote about a celebrity “rape club,” where world-famous actors were forced to sexually assault children to preserve their careers, and a “spectacular ritual killing” by a prominent political family. And he picked up the Jenkins rumors — the ones a commenter on his site had started — and ran with them. Nelson claimed that Jenkins’s coffee-table book, Room 23, which features photographs of celebrities in a penthouse suite in Beverly Hills, was really an advertisement for an escort ring and accused Jenkins of coercing vulnerable actresses into joining. After Jenkins was cast in The Real Housewives of Beverly Hills in 2021, he tweeted that she had “spent a LOT of time with Jeffrey Epstein.” Uncharacteristically, he posted what he claimed was evidence: a photograph of a woman he said was Jenkins laughing at a party with Epstein and Trump. When people pointed out that the woman was actually the model Ingrid Seynhaeve (Hilton tweeted at Enty that he was a “moron” and a “liar”), he refused to take it down, relenting only after receiving a cease-and-desist letter from Jenkins. In 2022, she filed a defamation suit against Enty, who had somehow never been sued before. Her complaint alleged that Nelson had intentionally invented these stories for profit, making ever more outrageous claims in a ploy to grow his site. (Nelson published an apology to her after settling the suit last June.) “Enty Lawyer has published fiction,” the lawsuit read.

Brian Pocrass, an attorney and producer, shared this view. Around then, Pocrass had begun producing a documentary, She Was Here, about Heather O’Rourke, an actress best known for playing a child sucked into a supernatural void in the 1982 horror film Poltergeist. For years, it had been rumored that people involved in the production of Poltergeist had been “cursed” in part because of O’Rourke’s sudden death when she was 12. But Nelson’s O’Rourke blind was of a different order. In 2017, he wrote that three men at a studio where a child actor had been filming a TV show assaulted her and “inserted something inside” her and that she died from the resulting injuries. The rumor quickly gained traction in conspiratorial corners of the internet, where Enty’s mainstream appraisal as a Me Too whistleblower lent it credibility.

O’Rourke’s death in fact had been well documented. Her parents had filed a medical-malpractice suit alleging that her doctors had failed to diagnose a long-standing small-bowel obstruction. Still, Pocrass wanted to do his due diligence and try to understand where the story was coming from. In the blind, Nelson claimed that an actress who co-starred with O’Rourke in the TBS comedy Rocky Road had supposedly witnessed some of the abuse and sent him a brief description of what happened that day. Pocrass tracked down the actress, who told him she’d never seen or experienced anything described in the blind. A teacher on the set told him the same thing, as did the actress’s mother, who was by her side throughout the shoot. He came to believe that whoever had written the blind — either Nelson or the person who submitted the tip — had made up the story out of whole cloth. It was not an accident, he argued, that Rocky Road was O’Rourke’s most obscure credit. “They did their homework, taking the least-recognizable credit on her IMDb, and made up an atrocious story,” Pocrass said. O’Rourke’s family told him about the pain the blind had caused them. “It’s enough what the family has gone through and then all of a sudden, 30 years later, to have people trash her memory and legacy with such absurd lies?” he said. “Of course they’re angry. Wouldn’t you be?”

Nelson took down the item in 2019 after learning O’Rourke’s family was upset. “I don’t know if I really thought about Heather’s family when I wrote the original story,” he told me. This prompted a realization: “Okay, well, this can affect people.”

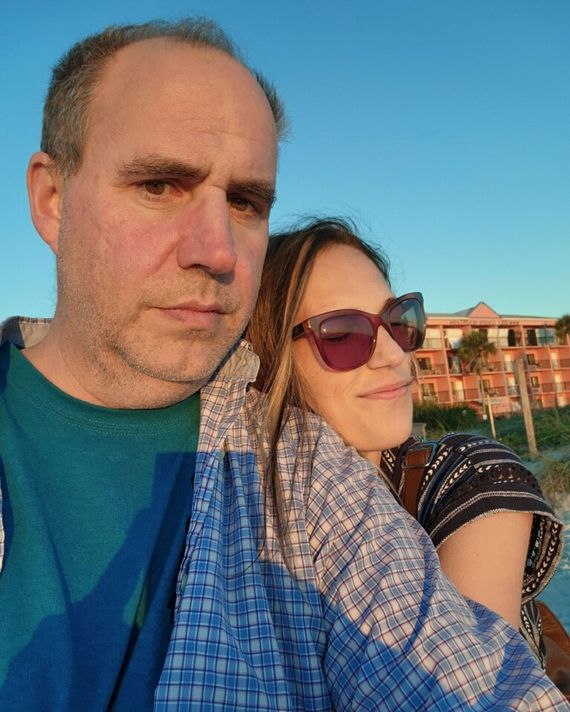

Nelson and Crose during his first visit to Florida in December 2022;

Photo: Courtesy of the subject

I met Cassandra Crose and her mother, Julie, a semi-retired accountant, in a pub near Crose’s apartment in Clearwater, Florida. Crose described herself as a hippie but was dressed soberly in a black T-shirt and black-rimmed glasses, her long dark hair tucked behind her ears. She riffled through a leather briefcase packed with court documents and removed a stack of papers. In his initial restraining order, Nelson wrote that he had attempted to break things off with Crose by blocking her, ignoring her, and telling her to stop contacting him. Crose said that wasn’t true. “He never tried to break up with me,” she said. “For someone who’s a fucking lawyer, you would think he would provide some actual evidence.”

Crose met Nelson in August 2022. She was a single mother of three who worked as an investigator for a gas-and-electric company; in her spare time, she hosted two podcasts: Cassandra Explains It All, in which she waxed nostalgic about the movies and television shows of her millennial childhood, and Welcome to the Carterverse, about the now-deceased teen pop star Aaron Carter. Two of her kids, ages 6 and 8, have special needs, and she couldn’t afford a babysitter. The podcasts were “something I could do at night when they’re asleep and that gave me a social life,” she said. “I don’t have a lot of friends.”

While researching episodes, she came across Enty, who seemed to know everything about the child actors of that era. For her 35th birthday that August, Crose spent $250 on his Patreon to co-host a podcast episode with him. She asked if they could do an episode about The Wonder Years. “I thought maybe he could give me tea on Fred Savage,” she said. After recording it, Nelson praised her work and invited her to host more episodes with him. Over the following months, they recorded podcasts about Full House and Growing Pains. Their email exchanges took on a flirtatious tone. He told her he’d been married and divorced a few times and was now living alone out in the desert. After sharing his real name, he told her not to worry about signing an NDA. “I didn’t want to have people in my life who had to sign NDAs to know me,” he texted her in October 2022. “So I just don’t have people in my life.” Later that day, he wrote again, this time to confess that he had feelings for her: “If I’m wrong or misunderstanding how you feel about me, please let me know.”

Crose hadn’t had great luck with men, she told me. She’d met the father of her kids — “a drug addict with an anger problem” — at a Rainbow Gathering in Arizona. Nelson seemed different. “He is not a drug addict,” she remembered thinking. “He doesn’t have a criminal record. He’s a respectable person. He’s a lawyer. I didn’t think someone like that would ever be interested in me.” Nelson was texting her dozens of times a day and calling her nearly every night. He told her he was thinking about moving to Florida so they could be together. He said he loved her, and she said she loved him too. Their texts became sexts. Nelson shared his fantasies of dominating and owning her. (“Give yourself over to me. Life will be so much easier,” he wrote.) Hoping to learn how to please him, Crose listened to a podcast about BDSM. They talked about buying a house together, getting married, having kids. In December, he visited for the first time.

Crose’s mother met him on that trip. He looked older than in the pictures he’d shared. “He said he was 47,” Julie told me. As they eventually learned, he was 54. Julie found him standoffish and controlling. At a restaurant, he told Crose to order a salmon salad. When the order arrived with candied pork belly, he picked each bit of pork off the plate. “He didn’t want her eating that,” Julie recalled. “He keeps looking at the menu and he’s like, ‘Oh my God, I can’t wait to move here. Everything here is so cheap.’ And I’m looking at her going, ‘He’s moving

here already? ’”

A week after his visit, Crose was contacted on Twitter by a woman who said she was Nelson’s wife. “You’re not the first person he cheated on me with. You won’t be the last,” the woman wrote. “He will despise you too, at some point. He doesn’t even care about his own children.” Nelson had never mentioned any children. Shocked, Crose reached out to Nelson, who apologized and assured her that he and the woman were separated. He claimed his ex was in denial about the end of the marriage. He said he hadn’t told her about their two kids, ages 10 and 11, because he was worried she wouldn’t love him anymore if she knew. He texted her that he was buying a ticket to Florida. “I’m going to move out there, even with you hating me,” he wrote. “I’m still going to keep all my promises.”

At the pub, Crose told me she “wasn’t in a position to say no.” He had said the things she wanted most to hear: that he would take care of her and her children, that he loved her and wanted to share his life with her. “I wanted to believe him,” she said. Her mother interjected. “It wasn’t just the want, it was the needs,” she said. He was sending her money through her Patreon, ordering groceries to her house, and offering to pay for her kids’ summer camp. The kids had eight specialized-therapy sessions a week. Someone had to take them while Crose was at work. “She needed the support,” Julie said.

That visit lasted three and a half weeks. He spent Christmas Eve with Crose’s extended family and cooked dinner every night. He picked the kids up from school, cleaned their rooms, did laundry, took them to their therapy appointments. He started paying for the appointments, too. Then one day in January, “he was acting weird,” she recalled. He texted her saying that he was at a bar and needed to buy a phone charger. He didn’t come back.

Over the next 24 hours, Crose sent him dozens of messages pleading with him to call her. She told Nelson she loved him. When he didn’t respond, she said she might be forced to go “public” about who he was and everything that had happened between them. That seemed to do the trick. Ten minutes later, Nelson called and said that he really was in love with her, that his marriage was over, and that divorce proceedings were underway. He claimed he’d returned to California because he felt guilty about abandoning his daughters.

Nelson said he would fly back to Florida later that month. When he failed to show up, Crose brought up a series of messages his wife had sent her. “It’s stuff that you probably would never want to get out there if I’m being honest,” she wrote in a text. His wife had told her that he didn’t know any celebrities and had never worked as an entertainment lawyer. “He just wants to feel special,” she’d written. “He makes up the blinds. He’s a grifter.” (Nelson said his wife was lying in order to make him “unattractive” to Crose.)

He returned for a visit at the beginning of February. They had sex. Nelson cooked dinosaur chicken nuggets for the kids. Once again, Crose thought that he’d returned indefinitely. He left for California after only two days. She said they never saw each other in person again.

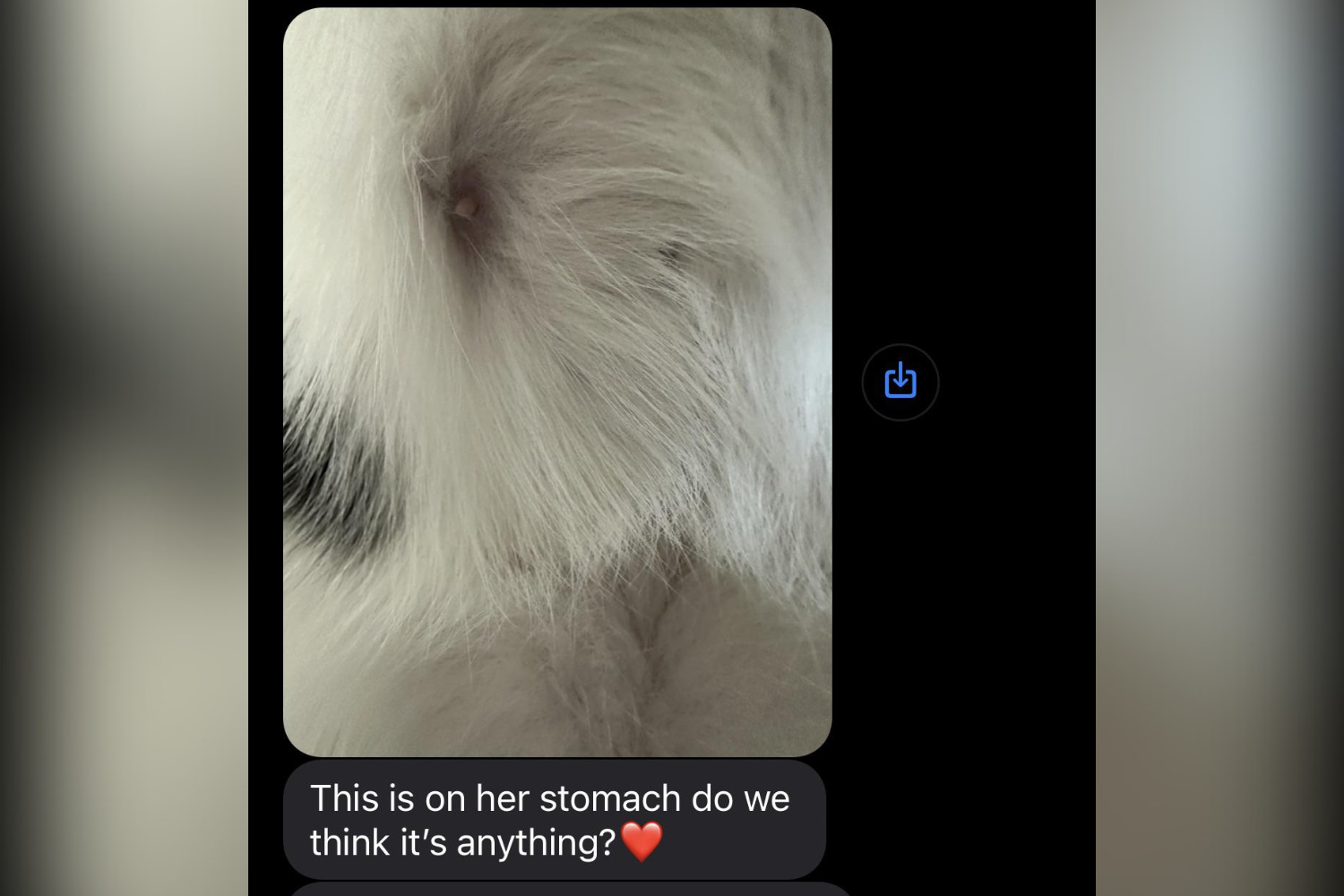

Over the next nine months, Crose repeatedly threatened to tell the world what had unfolded between them if she learned that he’d been lying to her. But she also told him that she loved him more than anyone she’d loved before. Nelson, likewise, told her he’d never done anything in his life that would make him “worthy to have someone like you as my wife.” At the pub, she turned her laptop around to show me months of Zoom invitations labeled “fun time.” “Every single night, he’s literally masturbating in front of me,” she said. Afterward, they’d watch the classic romantic-comedy seriesThe Love Boat together.

In March, Nelson said he was coming back to visit. He sent her photographs from the Tampa airport but never showed. He told her he’d had to fly back home to deal with an emergency. She later realized he’d found those photos online; he’d never been in Tampa at all. Whenever Crose confronted him, he had an excuse: He was stuck somewhere, his wife was drunk, his kids were missing school. Crose felt sorry for him and guilty for doubting him. When it came to men, she told me, she had a history of “burying her head in the sand.”

That summer, Crose asked Nelson for proof that he and his wife were really divorcing. Nelson emailed Crose what he claimed was a page from the divorce filings. She was reassured. They began to make plans for Crose and her three children to move in with him in California. Nelson made a shared Google spreadsheet to help them stay organized. In October, he sent her the names of the schools where the kids could go and told her he’d talked to the administrators. He also told her he’d booked a flight to Florida and would drive her and the kids back to California. Crose pulled her kids out of the specialized Medicaid therapy they’d spent years on a wait list to obtain. She notified the children’s schools that they would be leaving in the middle of the

year. The teachers arranged good-bye parties. Relatives gathered at her grandfather’s house to see her off. “She said good-bye to her grandfather knowing she’d never see him alive again,” Julie said. “The whole family is up there crying their eyes out.”

In November, after Crose had packed all their belongings, Nelson texted that his flight to Tampa had been delayed, then texted to say it had been delayed once more. “I have been on the phone with AA for the past hour,” he wrote. The next day, he wrote that he’d arrive that afternoon. “I love you,” he said. Thirty-two minutes later, there was a knock on Crose’s door. An officer from the sheriff’s department handed her a restraining order.

From left: During Nelson’s nearly monthlong visit in January 2023 Photo: Courtesy of the subjectCrose at home last November. Photo: Courtesy of the subject

From top: During Nelson’s nearly monthlong visit in January 2023 Photo: Courtesy of the subjectCrose at home last November. Photo: Courtesy of the sub…

From top: During Nelson’s nearly monthlong visit in January 2023 Photo: Courtesy of the subjectCrose at home last November. Photo: Courtesy of the subject

At the park in the desert, Nelson invited me to imagine that I had done something embarrassing when I was younger: “Let’s say when you were 18, you decided you were going to make a porn or something like that. Maybe you make three or four of them and then you forget about it. You go to college, you have a life, you have a really good career, but one where somebody will fire you if they find out about this or it’ll ruin your reputation. And then you get together with somebody and you think, Oh, well, I can trust them, or whatever. And you tell them your story. Then a few weeks later, you go, ‘Really, I don’t want to be with this person.’ And the first thing they do is say, ‘Well, if you’re not with me, I’m going to tell the whole world your secret.’” That had been his life for the past year, he said. “From January 15, 2023, until now. Every single time I wouldn’t call her back, she would say, ‘I’m going to blow up your world.’”

Nelson said he’d been feeling stressed and vulnerable when he first visited Crose. Jenkins, the socialite he’d falsely accused of running an international escort ring, had recently sued him, and he wanted someone he could confide in. He said he turned to Crose in part because she was one of the few people who knew who he was. She was also “an attractive person who knew what to say and was good at podcasting,” he told me. And then she “roped” him in with a story about her abusive ex and asked for his advice in case the guy ever tried to take her children away.

He said he wouldn’t have necessarily returned for a second visit if not for the fact that his wife found a Polaroid of him and Crose in his luggage. They fought, leaving Nelson with “no place to go.” When he and Crose discussed a possible return to Florida, he thought, “That’s not a bad idea. I’m pretty easily convinced.” One of his ex-wives told me later that Nelson was “extremely passive and completely anti-confrontational.” The ex, who asked not to be named, said her marriage with Nelson ended after she discovered he was cheating on her. (Nelson said this wasn’t how he remembered it.) Had she not left, she said, “I think he would have stayed married to me until he died.”

It was on his second trip to Florida that Nelson began to feel he’d made a mistake. He was taken aback when he realized Crose had told her friends and family that he was Enty. “My mom didn’t know,” he said. For two decades, perhaps just 20 people knew what he did for work. Now that number was closer to 30. “That really freaked me out,” he said.

He told me he barely remembered that three-and-a-half-week trip around Christmas. He was in a “fog,” he said. “Things got weird.” He said she was constantly asking him to do chores and help out with her children — not exactly the fun fling he’d imagined: “I had assumed the father mantle or whatever when I just met her literally for the first time a couple of weeks ago.” When he told Crose he missed his kids and wanted to go home, she said she already had made dinner plans with her mother and needed him to watch her kids that night. He felt Crose was keeping him a prisoner.

Nelson showed me a selection of texts Crose sent him over the course of that year. In April, she wrote to him, “If you don’t fucking call me back right now and apologize and have an actual adult conversation like I’m a human being, not a piece of abuse trash that you can just use and throw away I swear to Fucking God. I will literally show the entire world who you are.”

In his initial restraining order against Crose, Nelson claimed their relationship had ended in March 2023, a month after his final visit. (In fact, it continued through November.) He said Crose had stalked him and repeatedly threatened to dox him in an effort to harm his business and personal life. I asked if he had ever tried to simply break up with her. “All the time,” he said. What words had he used? Nelson hesitated. “You can’t actually say, ‘I want to break up.’ You can’t actually do that,” he said. Why not? “Because you literally get these texts every other day. ‘If you don’t call me, if you don’t do this, if you don’t do that, I’m going to ruin your life.’ Blackmail doesn’t have to be about money.”

Nelson admitted he’d repeatedly lied to Crose, telling her he was single and younger than he was, pretending to buy plane tickets he’d never bought, sending her photographs he hadn’t taken to make it look like he had tried to visit her when he’d never left Indio. Yes, he told Crose over and over that he and his wife were divorcing when they’d never even separated. He’d doctored a document to look like a page from a divorce filing that did not exist. And yes, he and Crose continued to meet on Zoom for “sexual activity” nearly every night for nine months — though he’s adamant he never monitored what she ate. (Crose shared many texts that indicate he did.) “Am I proud of it? No, but at the same time, again, I didn’t have a choice.” He claimed he was trying to stop her from “abusing” him. “Every day was just like, I hope today is not the day where I’m going to get yelled at.”

Throughout this ordeal, Jenkins, who had sued him, did not know his identity. He said he stayed with Crose in part because he worried that Jenkins would ruin him if Crose made good on her threats to expose him. It was only after the lawsuit settled, in June, that he resolved to end the relationship. But it took a few more months before he acted. He said the final straw came about a week before Crose and her children were supposed to join him in California, when Crose yelled at him on the phone for over an hour. The following day, he told a lawyer that Crose had “to be served because this is just spiraling out of control.” Over text message that same night, he wrote to Crose: “I can’t wait to destroy and fuck the hell out of you the first night you are here.”

In the park, he seemed astounded that Crose had taken him seriously. “It’s just like, How can she believe that we’re going to be together?” I asked what was going on in his head while he was talking with Crose about her plans to pull her kids out of school and therapy. He replied that Crose should have known better: “She didn’t have an address where she was going to move to. She had no clue. Would you take your three kids across the country and not know where you are going to live?”

The day after Crose received the stalking order, she and her friend Tiffany Busby, a nurse living in New Jersey, released the first episode of a podcast centered on the affair. Busby told listeners that Crose had been in a relationship with someone who was “diabolical” and, in Busby’s assessment, “incredibly famous.” They’d been planning to make a celebrity true-crime podcast called Drenched in Drama since the summer Crose first met Enty. All they needed was a subject. Now they had one.

Over more than 100 posts and episodes, Crose and Busby narrated the story of Crose’s relationship with Nelson with occasional detours into his history of false statements about Jenkins and O’Rourke and other related subjects. In retrospect, Crose saw Nelson as psychologically and physically abusive. She told her listeners he had groomed her, preying on her desperation for a partner and a father to her children before showing himself to be sadistic. She pondered the idea of rape by deception — when someone lies to obtain sex (a rare category of rape that American courts have largely rejected). Crose never consented, she told me, to being used by the man Enty turned out to be.

In her response to Nelson’s restraining order, Crose asked that the judge also bring a restraining order against Nelson, claiming he had threatened her life. On January 11, 2023, he allegedly told her, “I have killed women before and could kill you. I can make you disappear if I want, and I am smart enough to get away with it.” (Nelson told me that he’d never murdered anyone and had never said this to Crose.) Nelson, meanwhile, is pursuing a defamation claim against Crose, along with a second restraining order in federal court — this one adds that she had threatened to kill him too. (As evidence, he showed text messages in which she said “fucking die.”) He

also argued that some of her Patreon posts, which mentioned his minor children, put his kids in danger. The judge dismissed the complaint, in part because Nelson failed to follow procedural rules, and warned him against wasting the court’s time. When I asked Emily Sack, a professor at Roger Williams University School of Law, to review Nelson’s filings, she described them as frivolous. Then she paused to ask me a question: “Do we know if he’s actually an attorney? Because let’s just say that the documents weren’t particularly well done.”

In his daily life, Nelson is trying to carry on as if none of this ever happened. He posts at the same clip he has for the past 13 years — 13 small items a day and one big one. He usually records a podcast or two every evening. He says he lost 500 or 600 subscribers from his Patreon in the wake of Crose’s statements. But most people in his social circle still don’t know about his double life. “It can feel like the whole world must know about it,” Nelson said. “But in reality, it’s a tiny sliver of the population that really cares enough, right?”

On gossip message boards, hundreds of followers of the saga have denounced Nelson as a liar and a hack who was just as bad as — “and even worse” than, as one redditor put it — the celebrities he wrote about. Crose, or her Patreon listeners, have reached out to a handful of gossip writers and podcasters who linked to Enty’s work or did podcast interviews with him and warned them about him. A few cut ties with him. DeuxMoi, the modern-day queen of the blind item, who drew inspiration from Nelson’s approach, deleted podcast episodes she’d recorded with him. But most ignored Crose’s pleas. After all these years in the shadows, he was growing more popular than ever, and it was no mystery why. Despite all that talk of his Me Too heroism, people never went to him because he stood for truth or justice, and that is why they are not abandoning him now.

On TikTok, a place where falsehoods and conspiracy theories are circulated so widely and indiscriminately that experts warn of its eroding our ability to distinguish truth from fiction, his work has been embraced by a new generation of content creators. Watching their videos, you sense that Enty Lawyer, though only modestly successful, was in some ways a man ahead of his time. One rising star of the gossip world, “Celebritea Blinds,” a pretty young woman with blonde ombré hair and glossy lips who speaks in a robotic monotone, has built her audience of 337,000 followers by simply reading aloud from a website that pairs Nelson’s blinds with guesses. Recently, she proudly announced that she had received her first cease-and-desist letter. The person who sent it, she said, “has been accused of being a predator and abusing many people.” She paused, then added a caveat reminiscent of the one Nelson posted on his site all those years ago. “You guys know that all of what I read is alleged,” she said. “I don’t claim that any of this is fact.”