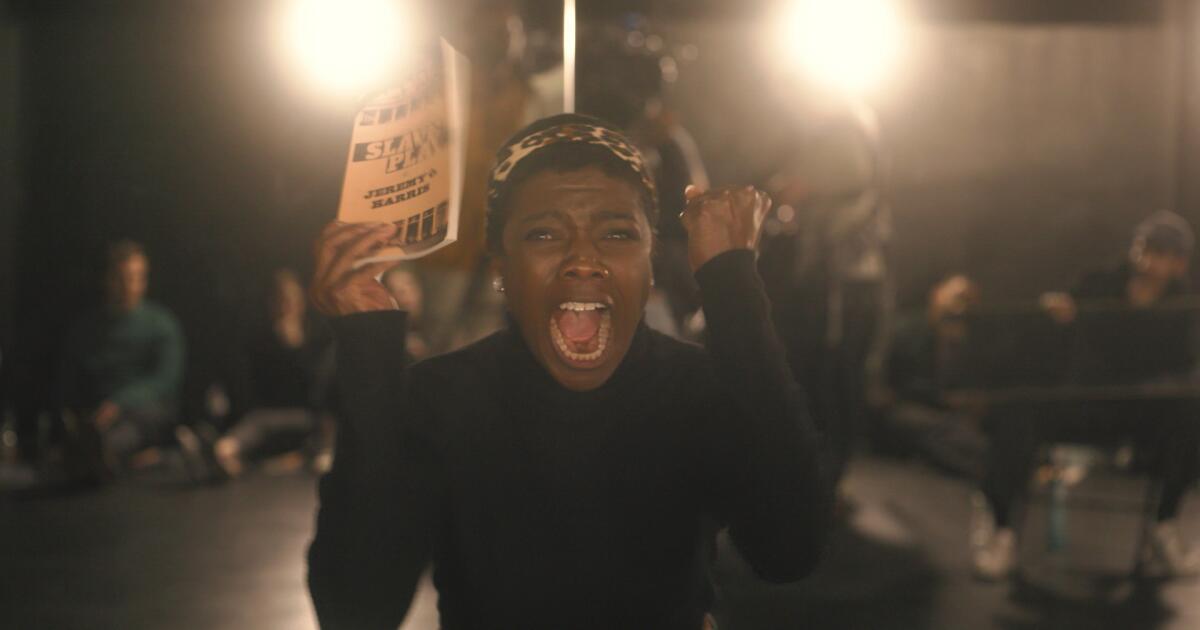

From Stereophonic, now at the John Golden Theatre.

Photo: Julieta Cervantes

The Act One particular climax of David Adjmi’s Stereophonic is a person of the most exhilarating moments I have seasoned in a theater in the latest memory. We’re in a recording studio in Sausalito, California, evoked in stunning depth, down to the smallest dial, the scuzziest beanbag chair and crocheted throw. The year is 1976, and an unnamed band, hovering on the verge of major fame, is recording an album. They’ve been at it for months. The air is clogged with cigarette smoke and cannabis smoke and rigidity as viscous as Marmite. The drummer, Simon (Chris Stack), does not want to use a simply click keep track of, but it is been 36 usually takes and he’s even now dragging. Diana (Sarah Pidgeon) sings wonderfully and has songwriting chops that get stronger by the day, but she’s fragile and defensive and feels continually below assault from her direct-guitarist boyfriend, Peter (Tom Pecinka), who’s amazing, creatively domineering … and also fragile and defensive and certain that he’s continuously below attack from, nicely, anyone. The wry, aloof vocalist-keyboardist, Holly (Juliana Canfield), has, for the minute, arrived at a détente with her philosophizing, self-pitying, cocaine-and–Jack Daniels–fueled spouse, the bassist, Reg (Will Brill), but hostilities could resume at any minute. The engineers, Grover (Eli Gelb) and Charlie (Andrew R. Butler), just want Simon to use the fucking click observe so that they can get the fucking take and everybody can go the fuck to sleep. Then — out of the blue, gradually, in some way both equally — a miracle occurs. Consider 37 is great. The tune bursts into driving, dazzling life. Persons toss down headphones and instruments and seize every other, hugging and hooting and doing stupid dances. Simon howls at the universe, “WE’RE These kinds of A Great BAND!!!”

Stereophonic is an echo-portrait of Fleetwood Mac and the tricky start of Rumours (Simon, Holly, and Reg are British and performed with each other for a long time before joining up with Peter and Diana, the Americans). It’s also a breathtaking feat of scoring by Adjmi — whose hypernaturalistic script captures the ebb and circulation of overlapping speech equally inside of and outside the studio’s audio room — and by director Daniel Aukin and composer Will Butler. Aukin and the show’s stellar cast play Adjmi’s rigorously produced, deceptively relaxed prose with as significantly exactness and audacity as the actors, all enjoying their instruments stay, pour into Butler’s tunes: Smart, perfectly-crafted tunes that mix the folks and blues and prog vibes of the ’70s with the soaring indie craving of Butler’s former band, Arcade Fire. (There’s a cast album on the way.) The display is aspect live performance and element break up drama, section seem-style marvel (Ryan Rumery is the hero responsible) and portion superbly observed time period piece (everyone’s legs appear dynamite in Enver Chakartash’s bells and flares, and that lovingly intricate established is by David Zinn). But it’s the thing Adjmi conjures up at the finish of Act A single that would make Stereophonic this kind of a meaningful and extraordinary piece of operate: In its bones, it’s a appreciate track, bittersweet and wounded and ferociously loyal, to the act of creating art — precisely, art that demands that most exhausting, infuriating, transcendent factor: collaboration.

“It’s a torture to need to have people,” sighs Holly. She and Simon — the Brits who are not constantly neck deep in substances — pleasure by themselves on retaining their composure. Simon is the supervisor and the designated group “dad,” and Holly has the form of excellent posture, posh vowels, and naturally regal mien that all the slumming in the globe can not tarnish. But no a person in the band is basically all right. They’re all damaged, all frightened, all specialists in hurting on their own or others or both of those. But there is a little something they’re capable of, even identified as to, amidst the consistent raging of egos and reopening of wounds. “I WANNA Engage in New music!” Peter bellows as he stomps from the studio’s control area, where by men and women are nevertheless passing all over the monumental coke bag and bitching about the broken espresso machine, into the seem area: the temple, the sacred space where by items get major, in which every person all of a sudden turns from a fucked-up human into a vital element of a complete.

Loads of artwork has been designed about the artist as egomaniacal monolith, as genius or tyrant or lonely freak. But Adjmi is on the lookout at something more intricate and contradictory — that ineffable matter that pulls a bunch of egos alongside one another. The torture and the elation of needing folks: Songs has it, and theater has it. And any person who’s thrown by themselves into both is familiar with that the very same challenge, the identical folks, can someway go away you more battered and drained than you considered probable whilst also staying, as Diana whispers, “the very best factor that ever happened” to you.

Ideal from the title, Adjmi has built into his engage in this fixation on the harmonies and discords of collaborative development. Stereophonic audio arrives at you from extra than one source, blended by the ear and the mind to type a better entire. Which is the endeavor for the show’s 7 actors: Equally on devices and as instruments, they’ve got to weave jointly individual lines of a exactly designed rating, and tempo and mix are all the things. This is the good trick of high naturalism: To audio the most “real” requires the most cautious listening, the most painstaking devotion to fashion. Adjmi’s script is orchestrated down to the conquer — pauses, overlaps, shifts in intonation all pointed out (a person of my most loved stage instructions: “proleptic apology”). Language like this requires an ensemble of athletes, alongside with a wonderful offer of have faith in — and the show’s transfer from Playwrights Horizons has only offered Aukin’s remarkable business additional time to improve collectively. No one misses a conquer, from Brill’s itchy, writhing, slurring, someway still unusually sweet mess of a bassist (just wait for his head-blown effusion on houseboats) to Butler’s cheerfully strange assistant engineer — his absence of space-reading through competencies is 1 of the show’s wonderful entertainments, and the band members’ repeated incapacity to remember his title is just one of its smaller, hilarious heartbreaks. Canfield gives the outwardly interesting Holly attractive depths — it’s devastating to hear her, enraptured, tears in her eyes, describe the intercourse scene from Don’t Seem Now as lovely “because you know it is coming from grief” — and Stack expertly turns Simon into that dude who’s at the moment the most lovable and least readable in the place. He appears to be like the peacemaker, the caretaker, the one particular who’s there to cheer you up with a bump from the bag and a tickle — but there’s also a distance in him, a charge that is been paid, a mountain of words and phrases unsaid.

As the quasi Lindsey Buckingham and Stevie Nicks figures, Pecinka and Pidgeon have to make the churning, molten emotional main of the play, and equally their chemistry and the sharp edges of their portrayals have only developed given that the show’s 1st operate. In contrast to her phenomenal voice, Pidgeon has located one thing a small uglier in Diana as a character, and it operates: It is all also attainable, specially given the teams that we are inclined to operate toward instantly these days, for the exacting, damaged Peter to turn out to be the show’s villain. Just pay attention to the viewers gasp when, after the band lays down an unquestionably using tobacco recording of a single of Diana’s tunes, Peter, stone-faced and toneless, hits her with: “It’s very good but … your ego is receiving in the way and you have to have to make your mind up if you are gonna be a mediocre songwriter or push it to the following amount.” Nevertheless it’s vital that we really don’t assign poor men and fantastic men in a demonstrate like this. Peter — to whom Pecinka fully commits, giving him horrible hardness, enormous hurt, and bravely daring to be anything at all but likable — has bought to be as human as Diana, as proper and as wrong, as sinned versus as sinning. Pidgeon and Pecinka have been nimbly messing around with the dials of their characters’ relationship like Grover at his soundboard, and have located a dynamic that feels marvelously sophisticated, a abundant, unhappy area where by it is no quick undertaking to position to a singular target.

And as for Grover — the character is the top secret heart of the display, concealed in basic sight at middle stage, as we concentrate on the colorful artists behind the glass wall. Gelb quietly crafts a long, aching arc with the suffering, aspiring, not-as-great-as-he’d-like-to-be engineer. He’s funny, he’s lost, and he’s also every inch an artist: devoted, formidable — finally, whether or not he likes it or not, equally a perfectionist and a believer. Grover, along with everyone else in this smelly, unstable studio, could shout alongside with Reg when, at the climax of a ganja-assisted revelation, he declares, “I want to reside in art.” It is not actually a joke — it may possibly even be a tragedy. Or it’s possible it will be the ideal point that ever happened.

Stereophonic is at the John Golden Theatre.