Last week two solo exhibitions bearing voluminous — and timely — insight arrived at Los Angeles museums. Each is a mid-career survey of feminist painting, sculpture and video from the past 20 years, representing two very different artists for whom women’s place in the world is key.

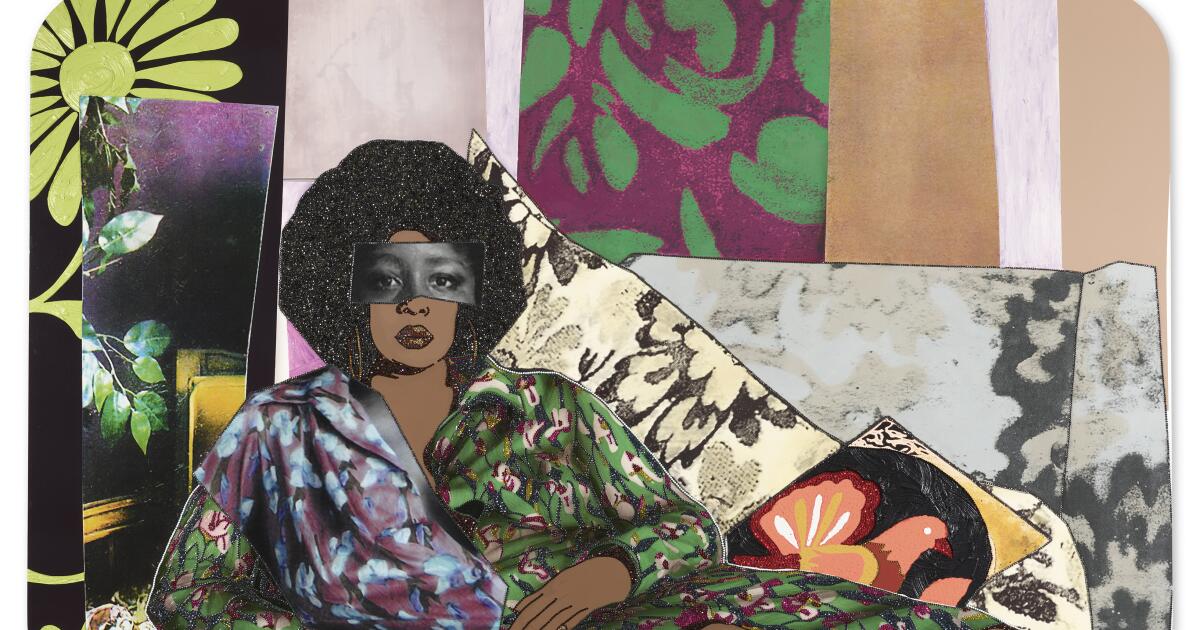

“Mickalene Thomas: All About Love” is a vibrant show of more than 80 paintings, drawings and mixed-media installations downtown at the Broad. Her work builds on a simple but trenchant observation: In the long history of Western painting, monumental portraits of Black women are almost nonexistent. Most of Thomas’ paintings pile on vivid color, brash patterning and lots of sparkling rhinestones, taking an exultant step toward rectifying the omission.

“Simone Leigh,” which is divided between the California African American Museum in Exposition Park and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art in Mid-Wilshire, features 27 sculptures and three projections. Sober history is essential to Leigh’s often elegant work, which gives equal weight to the two adjectives joined in the term “African American.” Women’s images are abundant, and multiple artistic traditions gracefully entwine.

The fact that both artists are Black adds to the timely relevance. During the Jan. 6 domestic terrorist attack on Capitol Hill, a few Black faces were glimpsed amid the scandalously waved Confederate, Gadsden and “Appeal to Heaven” flags, but it is worth emphasizing that the number of those faces that belonged to women was roughly zero. Today, in a nation exhausted by dealing with the tenacity of systemic racism and riven with conflicts over straight white Christian male supremacy, Black women sometimes seem to be the linchpin barely holding things together.

Journalist Marianne Schnall, founder of the influential website feminist.com, once aptly noted that “Black women are by no means a monolith, and yet as a group have a deep understanding of the relational nature of freedom, precisely because they sit at various intersections of targeted oppression.” Add queer identity to the mix, and the comprehension deepens further.

Simone Leigh, “Cupboard,” 2022; stoneware, raffia and steel armature

(Christopher Knight/Los Angeles Times)

Thomas’ show was co-organized by Broad curator Ed Schad and Rachel Thomas of London’s Hayward Gallery, where it travels next year. (Stops are also planned for the Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia and Les Abattoirs in Toulouse, France.) The Los Angeles debut opens with an elaborate stage set that replicates façades of tidy row houses in Camden, N.J., just across the river from Philly, where the artist was born in 1971. More than a mere conceit, the theatrical façades establish domestic settings as integral to Thomas’ aesthetic. On doorsteps, welcome mats are laid out.

Living rooms, rec rooms and finished basements turn up as installation formats throughout the show, while the compositions in her monumental portraits tightly collage figure and ground. The self-portrait in “Afro Goddess Looking Forward” is typical: Black-and-white photographs of Thomas’ eyes, some tabletop greenery and a portion of her torso mix with abundant painted features. The entirety of the figure is part of a dynamic patchwork that incorporates furniture, pillows, wallpaper and other accoutrements of a homey interior. Thomas presents as a Gen X Matisse.

Visually, there’s no separating the artist from her domestic environment, even in the imagination, so dazzlingly exuberant are the two fabrications. The strategy is repeatedly employed in paintings of friends, lovers and family, where figures merge with ground. The union comes across not as a limiting confinement but as a refuge — a contained space of at times boisterous play in which creative exploration unfolds.

Queer artists often regard the private home as a safe place for resourceful invention, given a public realm that puts forward scant models for living a life, not to mention offering abundant danger for doing so. Thomas is no exception. In one room lined with faux-wood paneling and cherry-red ottomans, she even shows herself in each painting twice, dressed in form-fitting animal-print tights and happily engaged in wrestling matches with herself. In another, an elaborate video montage of the brilliant and outspoken singer Eartha Kitt can be viewed from comfortably upholstered furniture in a convivial living room.

Then there’s her trademark use of craft-store rhinestones, which is multipurpose. Hair, body contours and facial features are often lined with the glittery paste, sometimes multicolored. The pictures’ flatly painted skin and two-dimensional patterning in textiles and wallpaper are set into shimmering visual motion. The paintings become performers, like entertainers on TV or the stage.

Forget Hobby Lobby. This sparkly craft-store aesthetic perform a vernacular consecration of the women she paints (and she paints only women). Rather than tacky, the rhinestones are beguiling. They make you smile.

Mickalene Thomas embeds her portraits of Black women in decoarative interiors

(Christopher Knight/Los Angeles Times)

Elsewhere, Thomas incorporates queer predecessors in paintings of abstract heads. A borrowed Andy Warhol “Flower” becomes an eyepatch, while topsy-turvy eyeballs, pushed to the margins of a face, recall Jasper Johns’ borrowing of similar elements from Picasso’s “Woman in a Straw Hat.” Thomas is identifying family.

Sometimes the pictorial setting is layered into the exhibition’s physical installation. One gallery filled with potted plastic plants features collage-style paintings of pin-up nudes from Jet magazine. Thomas has installed several of them on a wall dominated by a photo-enlargement of a pointedly empty closet. Jet cheesecake photos were surely made with male subscribers in mind, but she identifies lesbian desire as a vital element within the magazine’s audience. Black diversity is real.

Over at CAAM and LACMA, “Simone Leigh” is a traveling exhibition organized by the Institute of Contemporary Art / Boston, where it was seen last year. Included are several sculptures shown in the American Pavilion at the 2022 Venice Biennale, where Leigh, now 56, represented the United States. As at the Broad, male figures are nowhere to be seen.

Leigh has said that her work represents a “creolization” of art, mixing prominent European and Black traditions. Some of what is implied by the term is evident in the remarkable “Martinique.”

Simone Leigh, “Martinique,” 2022; stoneware

(Christopher Knight/Los Angeles Times)

Five feet tall, the cobalt blue stoneware figure of a lifesize headless women in a voluminous, bell-shaped skirt shows her cupping aggressive, bullet-like breasts in her hands. Titled for the island of Martinique, a former French colony in the Caribbean that legend held was once occupied solely by women, Leigh’s 2022 sculpture derives from a mid-19th century monument in the capitol, toppled during Black Lives Matter protests two years earlier.

The destroyed monument was a marble figure by French Salon artist Gabriel Vital Dubray that celebrated Martinique native Joséphine Bonaparte, first wife of Emperor Napoleon, who was instrumental in reviving slavery on the island despite its abolition in France. Dubray’s mediocre statue had already been beheaded three decades ago — a symbolic decapitation that couldn’t help but recall Marie-Antoinette’s actual fate at the guillotine. The sculpture stood headless in a public park until July 2020.

Think of Leigh’s subsequent sculpture as a monument to its headless-ness — at once a mockery of Joséphine’s thoughtless ignorance and a captivating salutation to the actual power of symbolic resistance. The volumetric, jug-like form of “Martinique” emphasizes clay’s eternal role as a vessel, which the artist fills with new meanings by virtue of her chosen forms and referents.

Clay is the medium most often encountered in Leigh’s art, whether in glazed form or as the raw material for works then cast in bronze. Shiny stoneware sphinxes in modulated natural hues, an 11-foot mound of raffia crowned by the feminine symbol of a cowrie shell, a suspended cluster of several dozen breast-shaped terracotta gourds with golden nipples and pierced by metal antennas — sculpture’s most ancient substance is typically made sleek and modern in her hands.

Mickalene Thomas installed pin-up paintings on a photo blow-up of an empty closet

(Joshua White)

Much of the work is a hybrid of female and architectonic forms — literally, woman as shelter.

“Herm” remakes an ancient Greek boundary marker or signpost, historically composed of a squared stone pillar with a carved male head on top. Leigh’s version employs a cruciform bust of a woman instead. A simple vertical slit is in front where a Greek phallus would protrude, and a shapely striding leg extends from the rear, together feminizing the bronze. Her signpost sculpture stands more than eight feet tall. Amazonian in scale, it insists that a viewer look up to the boundary it marks.

A bronze “Sentinel,” its surface featuring a rich black patina, transforms a traditional sphinx motif. A horizontal, corrugated body (think of the shape as a sheltering Quonset hut or nourishing grain shed) is topped at one end by a female head, its Afro hairstyle smoothed into a turban form. Incongruously, this watchful guardian’s face has no eyes, a motif common to all but one sculpture in the exhibition. The internalized, inward-looking result merges with a blank screen, onto which viewers project their own perceptions. Leigh’s best work generates a sense of intimate connection, even when its size approaches monumental.

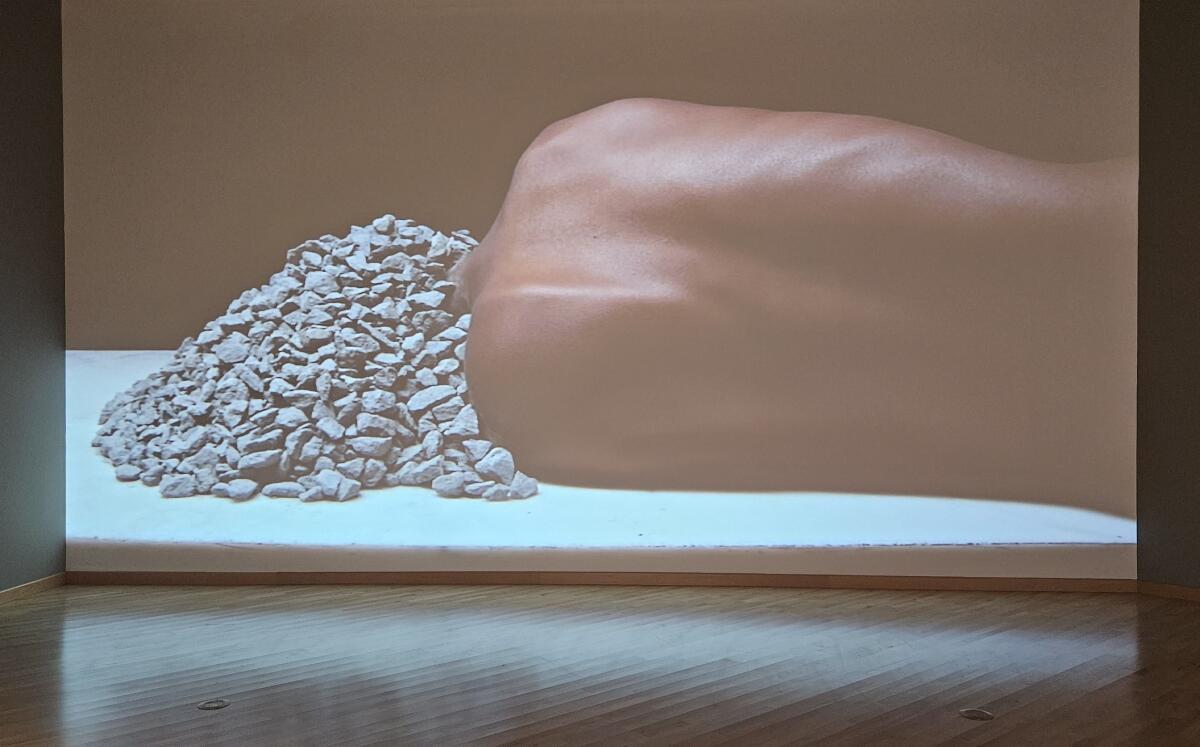

One moving work is a wall-size, single-channel video projection of a recumbent Black torso, seen from behind, the head obscured beneath a stony pile of gray rubble. Made in tandem with Brooklyn-based artist Chitra Ganesh — when they work together, the duo goes by the name Girl — it turns the European tradition of a reclining female nude inside-out, making the gender ambiguous and burying the figure’s gaze. (A wistful musical soundtrack, all wind instruments and drums, was composed by Kaoru Watanabe.) Look closely, and the mountainous image, seemingly static, is gently breathing. Whether the barely rising and falling ribcage represents restorative sleep or a dying breath is hard to say.

In both parts of the show, a bothersome hunt is required of visitors to find object labels too discreetly printed in black typeface against dark brown walls (a phone flashlight comes in handy). The only real downside, though, is the bifurcation between two venues located across town from each other. The split diminishes the retrospective punch.

The more satisfying presentation is at CAAM, where the 13 works span two decades, allowing for some sense of artistic evolution and reverberation. At LACMA, all but four of the 17 pieces date from just the past two years; the installation is lovely, but it’s more like a contemporary gallery show than a museum survey.

Simone Leigh, “Sentinel,” 2019; bronze

(Christopher Knight/Los Angeles Times)

The prominence of the exhibitions by Thomas and Leigh — highly accomplished, queer Black women — is crucial, however, especially as June’s Pride celebrations commence. At least 515 anti-LGBTQ bills, a record number, are pending in state legislatures across the country, representing an unspeakable mass of public hate. Misogyny, a core driver of homophobia, is deeply embedded in American life.

It has been since at least 1692. That was the year Bridget Bishop was ascertained to be a witch by frightened, conformist Puritan religious elders in the Province of Massachusetts Bay. Bishop, a thrice-married mother of four, was hauled away and lynched on Gallows Hill in Salem Village after a bizarre eight-day trial.

Three centuries later, as a criminally convicted former U.S. president bellows “witch hunt” into every available microphone, the madness endures, the cruelty continues. When Supreme Court Justice Samuel A. Alito Jr. and his cohort stripped women of bodily autonomy in overturning long-settled abortion rights two years ago, the conservative Catholic jurist resurrected the discredited opinions of British judge Matthew Hale for support. Hale, a Puritan sympathizer and later Lord Chief Justice of England, sent two women to their doom as “witches” after a trial in 1664.

Alito’s absurd citation of a notorious misogynist was widely greeted with a mix of disgust and ridicule, but not surprise. (Even though a nearly two-thirds majority of Americans say abortion should be legal in all or most cases, we live in a country where rule by a political minority is the norm.) Thomas and Leigh, judging from their generous and eloquent paintings, sculptures and videos, are unlikely to have been shocked. Saddened, for sure, and no doubt even scandalized — but not shocked.

More’s the pity. And more’s the reason for their bracing art.

Girl (Simone Leigh and Chitra Ganesh), “my dreams, my works, must wait till after hell. . . ,” 2011; single-channel video, color, sound, 7:14 min.

(Christopher Knight/Los Angeles Times)

Mickalene Thomas and Simone Leigh

Mickalene Thomas

Through Sept. 29 (closed Mondays) at the Broad, 221 S. Grand Ave., L.A. (213) 232-6200, www.thebroad.org

Simone Leigh

Through Jan. 20 (closed Mondays) at the California African American Museum, Exposition Park, 600 State Drive, L.A., (213) 744-7432, www.caamuseum.org; and also the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 5905 Wilshire Blvd., L.A., (323) 857-6000, www.lacma.org