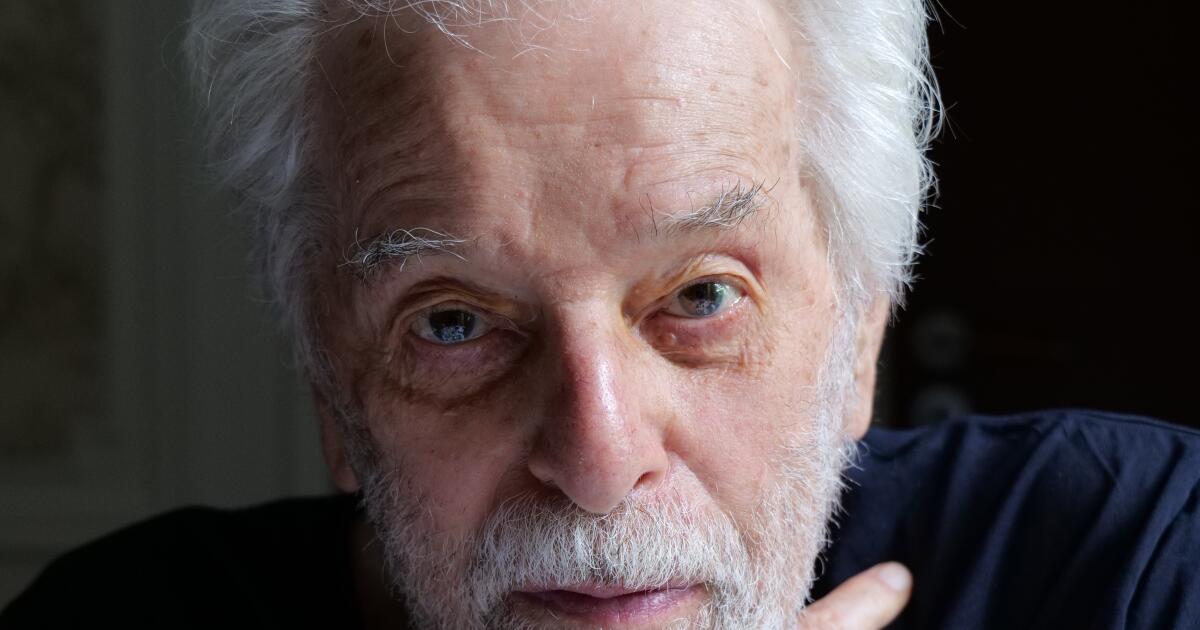

Michael Govan, photographed at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art in Los Angeles on Nov. 14.

When Michael Govan joined the Los Angeles County Museum of Art as director in 2006, he had a vision: to create an arts and culture town square, in sprawling and diffuse Los Angeles, along museum-heavy Miracle Mile. He had a 340-ton boulder hauled from a Riverside-area quarry to the Wilshire Boulevard museum in 2012 for a monumental sculpture, by Michael Heizer, to mark his LACMA campus. The artwork, “Levitated Mass,” is a beacon of sorts, visible from the street.

Discover the changemakers who are shaping every cultural corner of Los Angeles. This week we bring you The Civic Center, a collection that includes a groundbreaking mayor, a housing advocate, a giver of food and others who are the backbone of Los Angeles. Come back each Sunday for another installment.

A specialized “transporter,” nearly three freeway lanes wide, carried the two-story-high boulder, which was shrink-wrapped and illuminated with string lights, very slowly over 11 nights — it traveled 5 miles per hour, through four counties and 22 cities, not unlike an evolving, mobile performance art piece. It drew crowds into the hundreds, with spectators wandering onto their porches or front lawns, in their pajamas in the middle of the night, as the spectacle inched toward the museum.

It was equally a feat of transportation engineering and a logistical nightmare (traffic lights and power lines were reconfigured). But the project drew global marketing for the museum, with international TV crews covering it. And it was a harbinger of things to come: Change was on the horizon at LACMA. And, like Govan’s monolith, it was going to be big.

‘Michael has been tenacious in reaching the goal he set of reimagining what LACMA will be.’

— Christine Anagnos, executive director of the Assn. of Art Museum Directors

Govan — famously camera-ready, with a slender frame and seemingly elastic smile — has since cemented himself as one of the city’s most influential, if not divisive, arts leaders. LACMA’s $750-million new building — now about 80% complete and targeting a late 2024 completion — is one of the highest-profile new museum projects globally. And it’s rising amid a Los Angeles museum boom and commercial gallery expansion; the city now hosts one of the most active art scenes in the world. And LACMA is at the center of that activity.

But Govan’s new museum building has also been a lightning rod for controversy. The cost — $125 million of which is coming from Los Angeles County taxpayers — has been an especially heated issue. Govan insists the project’s price tag has not risen despite breaking ground during the COVID-19 pandemic, coupled with subsequent labor challenges and supply-chain issues, problems that slowed other museum construction projects such as the Lucas Museum of Narrative Art. Not to mention inflation.

LACMA holds that construction costs were contractually “locked in” as of August 2020 and that additional costs are being covered by a contingency budget, explaining why, the museum said, the overall cost hasn’t risen.

A project of this magnitude is “very rare because of its scope and its ambition,” said Christine Anagnos, executive director of the New York-based Assn. of Art Museum Directors. “You don’t see a lot of museum buildings come up from scratch — it shows real dedication to the city. Michael has been tenacious in reaching the goal he set of reimagining what LACMA will be.”

To say that there are varying opinions about Govan’s vision for what LACMA “will be,” however, is an understatement.

Architectural preservationists still mourn that Govan razed four longtime LACMA buildings to make way for the Peter Zumthor-designed David Geffen Galleries: William L. Pereira’s 1965 Leo S. Bing Center, his 1960 Hammer and Ahmanson buildings and Hardy Holzman Pfeiffer Associates’ 1980s Art of the Americas building. And the new building’s design — an amorphous-looking, raised, single-story exhibition hall straddling Wilshire — has been hotly debated. Some see the modernist building as innovative from a design front while others liken it to a freeway overpass. But at the heart of the controversy lies the fact that the new building will be smaller, featuring a total of 110,000 square feet of gallery space instead of the combined, roughly 120,000 square feet of the four demolished buildings. Times critic Christopher Knight dubbed it “The Incredible Shrinking Museum.”

‘To say that there are varying opinions about Govan’s vision for what LACMA “will be” … is an understatement.’

Govan’s vision for the new LACMA — a nonhierarchical, decentralized “21st century museum” that is flexible and accessible to everyone — is an honorable one. Some art world insiders have called him “visionary” and “ahead of his time.” But others fear the new building will be the downfall of the largest art museum in the West. LACMA’s encyclopedic collection has, for more than 60 years, presented global art history across thousands of years that schoolchildren, say, could find easily and visit regularly; the new LACMA will feature art from the museum’s permanent collections in rotating, cross-departmental special exhibitions.

The Ahmanson Foundation, LACMA’s largest donor of European Old Master paintings and sculptures, so disagreed with Govan’s reformatting plans, which don’t include permanent displays of signature works, that it ended its five-decade partnership with the museum in 2020.

“We all know the ramifications of this,” said architecture writer and longtime LACMA critic Greg Goldin. “We’re never gonna see the great majority of art in the museum’s encyclopedic collection. Which has meaning. It has meaning because it’s a repository of every aspect of global culture. And how you approach that, curatorially, is profoundly impacted by what the building is capable of and if the building is large enough to dig into those collections. But the new building, it’s a museum in storage, and will remain permanently in storage — and with enormous debt.”

“It’s hard, if not impossible, to see this new project as a win,” Rob Hollman, executive director of the advocacy group Save LACMA, adds, referring to the museum’s $619 million in debt and about $128 million in other liabilities — a total of about $747 million, according to its most recent 990 tax filing.

Others vehemently disagree.

Stephan Jost, director of the Art Gallery of Ontario — which broke ground in May on a new, $73-million modern and contemporary art wing — calls Govan’s approach to the new LACMA building “genius.”

“He’s hired an architect whose buildings exude permanence. They’re elemental, huge solid blocks of granite. They feel like they’ll be around in 1,000 years — in a city that’s known for tearing things down,” Jost said. “And the nonhierarchical structure — that nothing is fixed, it’s all flexible — means L.A. County will be the most responsive to art. There’s no bias, no white supremacy built in. L.A. County will be in sync with the people of today. No one’s going to remember the budget in 10 years!”

Govan has spoken of satellite locations to feature additional art from the collections and to widen the museum’s geographic reach, including in South Los Angeles. And LACMA has forged community partnerships throughout L.A. County to display art from its collections, such as at Charles White Elementary School. But no dedicated satellite locations have materialized yet. The museum said that one, at South L.A.’s Magic Johnson Park, in collaboration with L.A. County, is in the “early stages of planning.”

Govan, 60, came to LACMA from New York’s Dia Art Foundation, where he served as director from 1994 to 2006; before that he spent six years as deputy director of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. But the new LACMA building will be his legacy — in Los Angeles and in the art world. As such, Govan has ensured that LACMA has grown, in many ways, under his leadership.

Govan’s vision for the new LACMA — a nonhierarchical, decentralized ‘21st century museum’ that is flexible and accessible to everyone — is an honorable one.

Even as LACMA’s overall exhibition space shrinks with the new Zumthor building, the museum’s campus has expanded — and its visitorship has risen — during Govan’s tenure. He debuted the Broad Contemporary Art Museum in 2008 (planned before his arrival) and spearheaded the debut of the Lynda and Stewart Resnick Exhibition Pavilion for temporary exhibitions in 2010. In addition to “Levitated Mass,” Govan commissioned several large-scale works for the museum’s campus, including Chris Burden’s now-iconic “Urban Light” (2008), Barbara Kruger’s “Untitled (Shafted)” (2008) and Robert Irwin’s “Primal Palm Garden” (2010).

During Govan’s tenure, LACMA has grown its permanent collection too, through donations and purchases, by more than 44,000 works. And annual attendance has nearly doubled from about 600,000 to an average of more than 1 million.

Govan is also a savvy, charismatic fundraiser. In August 2023, the museum announced that it had surpassed its $750-million capital campaign goal for the new building — a chunk of those funds acquired during the uncertain times of the pandemic. The campaign now stands at more than $779 million. Govan has also expanded the museum board by 14 members since 2020, bringing in $353 million in board contributions to date.

“He’s going to get this done,” said art world observer Paul Schimmel, formerly chief curator of L.A.’s Museum of Contemporary Art. “And it will put not just him, but Los Angeles on the map. Whether some people like the building or not.”

Govan’s new museum, a county museum, will belong to the public. It will change the face of Los Angeles. For better or worse? That remains to be seen. By the end of this year, we might have a clearer idea.