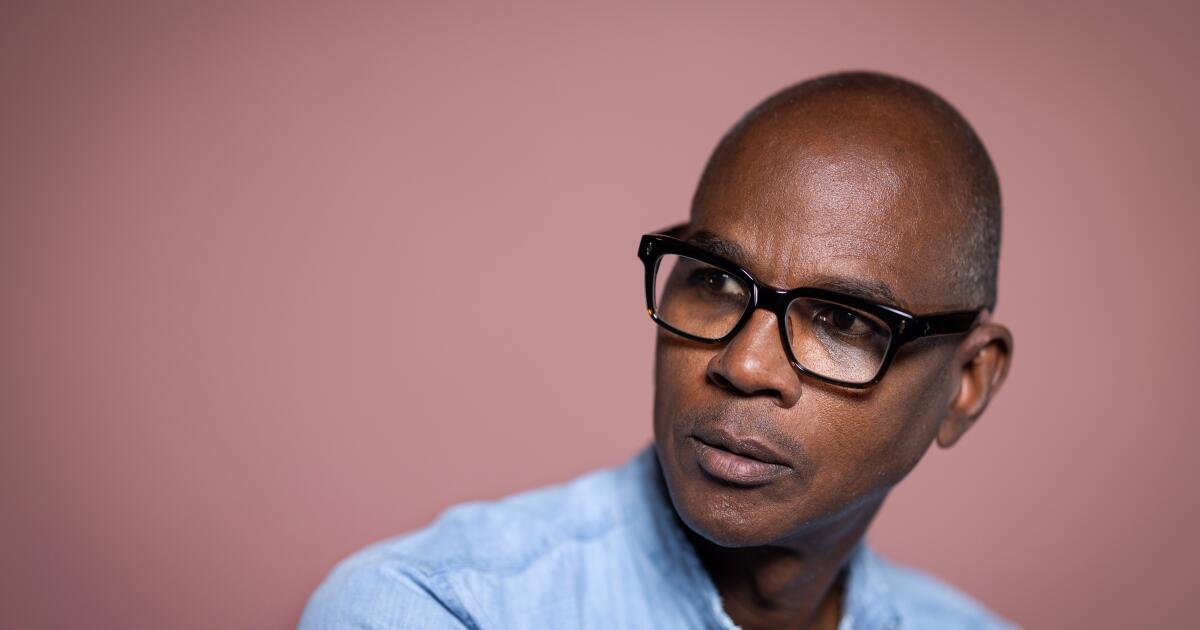

Mark Bradford, photographed at the Los Angeles Moments in El Segundo on Oct. 4.

Mark Bradford acquired a late start out as an artist. A former hairstylist, he did not start out to get the job done with severe willpower until eventually he was 30, when he enrolled as a painting student at CalArts in Valencia. His first exhibition to obtain common traction waited until finally he was 40 “Freestyle,” a 2001 group display of American artists proposed the emergence of “post-Black art,” function that inevitably encompassed Black encounters (and, in Bradford’s circumstance, queer activities as very well), but insisted that it not be ghettoized by race or sexuality. Substantially the identical way that Black heritage is American background, Black artwork is American artwork.

Now 62, Bradford ranks between the leading artists to have emerged in — and outlined — American artwork in the 21st century. Not too long ago he shocked many with a new sculpture, “Death Fall 2023,” a 10-foot guy sprawled on the ground, his pose lodged someplace in between a joyful, homosexual ballroom-tradition dance move and a gruesome murder target. It performs in opposition to Bradford’s achievement of having revived dormant abstract painting in a time dominated by figurative imagery.

His sway stems from far far more than multimillion-greenback product sales in an overheated artwork current market, despite the fact that a $12-million auction of his monumental canvas “Helter Skelter,” a 34-foot-vast meditation on the race war Charles Manson envisioned starting, is absolutely nothing to sneeze at.

Bradford’s U.S. representation at the 2017 Venice Biennale is much more to the position. He opened the five-place exhibition with a bulbous, abstract painted sculpture suspended from the ceiling that just about loaded the house. Evoking a bodily tumor, the unappealing mass crowded website visitors against the walls.

Bradford titled his exhibit “Tomorrow Is One more Day,” the cringey line spoken by Vivien Leigh’s weepy Scarlett O’Hara at the melodramatic near of “Gone With the Wind.” Her remark minimized a brutal background of white supremacy whilst auguring its endurance. The Oscar-laden passionate fantasy released a thousand pop society satires, though Bradford marshaled the homosexual dialect of camp in defense of moral seriousness.

Developing on the identified-item aesthetic of L.A. predecessors these kinds of as Noah Purifoy, who made assemblages out of the charred remnants of the 1965 Watts riots, Bradford also constructs paintings from canvases densely layered with road signage scavenged from fences, phone poles and city partitions in South Los Angeles, in which he was born and will work these days. And the MacArthur Fellowship winner, who also won this year’s $500,000 Getty Prize, served open Art + Apply, an exhibition room in Leimert Park.

Because the get started of the Black Life Make a difference movement, museums have targeted on contemporary art’s presentation of Black figures, but Bradford’s internationally acclaimed work demonstrates the continuing ability of abstraction.