The L.A.-based author Chris Kraus, an inspiration for many contemporary novelists.

(Arielle Bobb-Willis / For The Times)

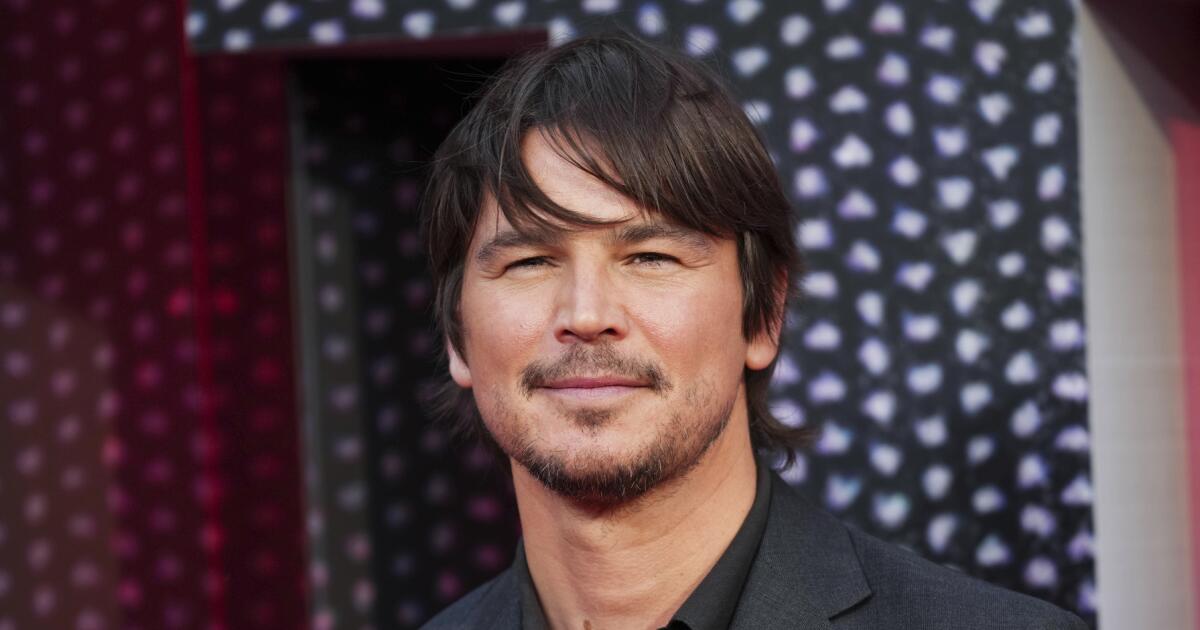

When I told a writer in New York I was going to meet Chris Kraus, she almost couldn’t believe it. For many, Kraus’ reputation as the author who has inspired so many contemporary novelists almost eclipses the fact that she’s also a person, an editor, a Californian, someone you can just email. Friends in Los Angeles were less shocked by the idea that Kraus, a longtime resident of MacArthur Park, could be both legendary and human, as she’s often seen at readings and events, especially for the books she fosters and publishes at Semiotext(e).

Kraus is best known for the novel “I Love Dick,” which first appeared in 1997 but caught a second wave of popularity in the Obama years, and then again in 2017, when it was adapted into an Amazon limited series. The main character’s epistolary obsession with a man named Dick warps into a kind of “performative philosophy,” an activity that perhaps all of Kraus’ novels are engaged in. She dismisses questions only to immediately ask them: “As if sex could provide the missing clues. Can it?” She makes digressions that veer into cultural criticism, but with so much more wit and excitement than you usually find in “cultural criticism.” I could list dozens of reflexive, confessional, philosophical novels of the last decade that owe at least some of their existence to Kraus’ work, either directly or indirectly, though my complaint is that too many of them lack the subtle balance between patience and exuberance that keeps her fiction so agile.

In 2017, Kraus published an exhilarating and somewhat nontraditional biography of Kathy Acker, who died in 1997. “After Kathy Acker” brought a writer who had long puzzled me vividly to life and was a guide and inspiration for my last novel, which was the reason Kraus and I first met in spring of this year. In person, Kraus is entirely gracious and kind and just the slightest bit shy. Like many of her narrators, she asks sincere questions and listens for the answers. I admire Kraus’ wit and rigor, and it was a pleasure to exchange these messages as I tried to glean the wisdom from a writer a generation ahead of me who has managed to keep art and literature at the center of her life.

Chris Kraus wears Prada dress, tights and shoes.

(Arielle Bobb-Willis / For The Times)

Catherine Lacey: Do you have a routine in your mornings when it comes to reading, writing and thinking? Do you hold certain hours in reserve for creative work? I ask because I feel my own sense of routine has vanished and I’m wondering if it’s a period of just being lazy and indulgent or if getting older is helping me shed a need for panicked productivity.

Chris Kraus: I only put myself on a schedule if I’m working on something, and I’m not working on something every day. But the schedule is pretty structured when I use it and it mostly involves making sure that writing is the most compelling and interesting part of the day. There can be other things so long as they’re tepid — the reality of the book has to be the most real thing going on. I usually work in the mornings and early afternoon and sometimes try to channel my sleep to wake up with answers I couldn’t have found otherwise.

CL: Do you have any techniques for getting your sleep to bring answers?

CK: Banning electronics in the bedroom. I just think about the thing before going to sleep and often wake up knowing the answers.

CL: It’s so easy to forget how much power our devices have over the subconscious. When we met in Los Angeles last month, you mentioned there’s a draft of a new novel. Is this your first novel since “Summer of Hate”? What’s changed about your novel-writing process over the years?

CK: Yes and no. I wrote the Acker biography after “Summer of Hate,” and even though it was a literary biography, I approached it like a novel in terms of selection and shape. I think the reason I’ve written so few novels, relatively, is because each one is different. I have to write from a different place every time, and you can’t force that — and then the novel has to find its own form.

Chris Kraus wears Loewe dress, Stella McCartney shoes, Bottega Veneta earrings.

(Arielle Bobb-Willis / For The Times)

CL: And what can you tell us about the new novel? Where and when is it set? In an interview with Gary Indiana you said, seemingly about his fiction, “You can mix it up, but you can’t make it up.” Is that true for you also? Is it true for the new book?

CK: Yes, definitely. I hardly ever make anything up, it’s all in the selection — which, if you think about it, is almost infinite. My new book, “The Four Spent the Day Together,” is actually three short novels alongside each other. Together, they span about 75 years of American popular history, from my parents’ lives in the aspirational working-class Bronx, to me and my former spouse’s experiences with culture, cancellation and addiction in the 2010s, to the lives of some kids in northern Minnesota I followed in the wake of a violent methamphetamine crime in 2019. Over those years, almost a century, you do see a devolution — from my mother studying Latin and French at public high school to the Minnesota kids attending “online-only” school, which is like no school at all.

CL: You started making experimental films in the ’80s and ’90s but you’ve reportedly called them “pathetic” and “unwatchable,” though a critic in Artforum recently disagreed with you. Do you still think that about your films? When you look over your body of work now, what do you see? Have you found yourself capable of looking at it with the kind of distance that you can look at another person’s work, or is such near-objectivity too much for any artist to ever hope to mature into?

CK: I try not to look back. My impulse is to flinch … whenever I finish something, it’s as if it was done by another person and I’m a little afraid to engage. I looked back at the films a few years ago when they were exhibited at Liv Barrett’s gallery Chateau Shatto, and what struck me most was how many of the people in them are no longer alive, how the films are like a boat ferrying certain disappeared worlds into the present. I’m glad to have done that. Other than that, I just have to trust other people’s responses to work once it’s done.

CL: I love this idea of the work ferrying disappeared worlds into the present. Are books such a ferry too? Do you see books and films as relating differently to the viewers or readers who come decades after they’re first made?

CK: Yes, it is different, don’t you think? Why is it that mortality is often the first thing that’s conjured for people through film and photography? Often the first thing that people think watching an old film is: These people are all dead now. But people never think that way about a book. Maybe because a movie gives us actual people as they were at that moment, frozen in time. But a book is always entirely its own world — whether it’s something that came out this season or two or three centuries ago, a book is something the reader chooses to enter that can be read different ways but is totally sealed.

CL: I think that’s what I like about books the most, how they’re the most intellectually intimate of the arts, which is maybe one of the reasons that reviews can feel so intrusive and strange. How has your relationship to criticism of your work changed over time?

CK: I’ve always found it excruciating to read criticism of my work, whether it’s positive or negative. Which is really unfair — a number of very intelligent people have put energy into writing about it and I pretend, but I really cannot engage.

Chris Kraus wears Miu Miu sweater, jacket, skirt, shoes and bag.

“[W]henever I finish something, it’s as if it was done by another person and I’m a little afraid to engage,” says Kraus.

(Arielle Bobb-Willis / For The Times)

CL: Everyone advises writers to let reviews have no effect, but I agree that pretending not to care is the most that most of us can manage. It seems to me that much of the critical response to “I Love Dick” missed the mark when it first came out, but that the second wave of critics understood it better. Did it seem that way to you? And what was it like to see the book translated into a series?

CK: When people reviewed “I Love Dick” negatively in the late 1990s I was thrilled. At least they’re paying attention! When it was reprinted in the mid-aughts, the critical response was so much more in sync with the aims of the book. It found its readers. When the book was adapted, I knew it would feel weird. They did a good job, but becoming a named character in a sitcom was never my dream. Still, having the book circulate on that scale created these little communities of readers and that was nice.

CL: You were with Sylvère Lotringer for many years, but long after your divorce you still worked with him at Semiotext(e). I’m not one of those people who thinks that one’s personal life is somehow separate from one’s artwork or creative development, and I don’t imagine you are either. This is probably an impossibly large question, but could you tell me something about what effect his influence and companionship had on you as an artist and editor? What was the relationship like in the beginning, middle and end?

CK: I met Sylvère when I was 25. Before that I was a fan of his work. He was the most powerful influence, and he was immersed in everything that seemed important and glamorous to me at the time. At the height of our couple, we were a two-person cabal, scheming and dreaming but not taking anything too seriously. There was an age and maturity gap, and as I got older things changed, but we remained committed to each other as collaborators and intimate friends. Our co-editor, Hedi El Kholti, who became managing editor of Semiotext(e) in 2004, was incredibly patient and gracious when things got rocky during our legal divorce. All three of us valued the work of the press over passing grudges and feelings and moods.

CL: I think that’s so beautiful. I suppose it helped to have a common goal in Semiotext(e) through it all. I’m a fan of so many of the writers you’ve published and edited. Running a small publishing house in the United States is increasingly important as traditional publishing takes fewer and fewer risks. What is the most difficult part of your job? When you first started working with Semiotext(e), did you think it would be a part of your life for this long?

CK: Sylvère started Semiotext(e) in 1974. The press has existed for 50 years! That’s almost unheard of for an independent artistic enterprise, especially in the U.S. When I started working with Semiotext(e) in 1991, I never imagined it lasting this long. Still, our move to L.A. in 2001 was one of the things that helped us survive. At this point, Semiotext(e) is a shared vision between me and Hedi that resonates deeply with Sylvère’s interests and work. Hedi has advanced and professionalized Semiotext(e) to a point where it has a real presence, and at the same time created an artistic family and community of readers. I’m amazed that it’s traveled this far.

“[A] book is something the reader chooses to enter that can be read different ways but is totally sealed,” says Kraus.

(Arielle Bobb-Willis / For The Times)

CL: What else (specifically or generally) are you amazed by lately?

CK: There are people who inspire and amaze me. Most recently, the future animators and gaming designers who were in my last Art Center writing class. A whole other form of intelligence, I was in awe. And Agatha, my dog — how fast she runs in the woods when I let her off the leash.

Production Mere Studios

Makeup Daphne Chantell del Rosario

Hair Takuya Sugawara

Styling Assistant Isabella Manning

Catherine Lacey is the author of five books, most recently “Biography of X.”