Oh, we’re dancing now.

Photo: Theo Whiteman/Theo Whiteman

Want to watch House of the Dragon with us? Sign up for our new subscriber-exclusive newsletter obsessively chronicling season two.

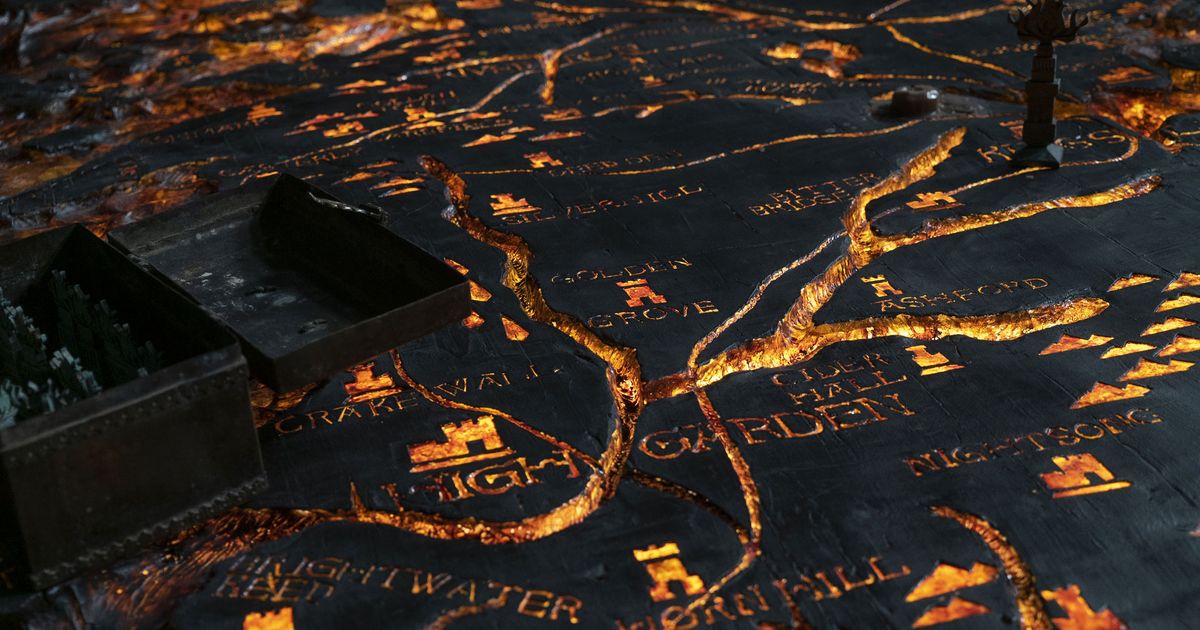

HBO may be burning Game of Thrones spinoffs (pardon me, “successor shows”) left and right, but House of the Dragon still stands tall. Now featuring Ryan Condal as solo showrunner following the departure of Miguel Sapochnik, the Targaryen-focused prequel returns for vastly improved second servings this week, trading a languid storytelling pace, tonal inconsistencies, and several instances where you couldn’t see anything for a tighter focus, crisper visuals, and a genuine sense of payoff. As the civil war between Queen Rhaenyra (Emma D’Arcy) and King Aegon II (Tom Glynn-Carney) — but actually his mother, Alicent (Olivia Cooke) — escalates, House of the Dragon (at least, the four episodes of season two made available to critics) finally achieves takeoff, delivering on its promise of a blood-, tears-, and dragonfire-filled epic tragedy. Here’s why the series hasn’t just become a better hang but a better-realized version of itself.

Despite the pomp and circumstance, House of the Dragon’s first season felt like one long throat-clearing sound. Much of the onscreen action manifested as explanatory material setting up the chessboard for the main story to come — a prequel to the prequel. Characters were mostly confined to a process of becoming, not being, and so a lot of the season delivered origin stories in miniature: how Princess Rhaenyra and Queen Alicent arrived at opposing positions; how Prince Aemond lost his eye; how Ser Criston Cole became an edgelord, etc. Season two plunges us straight into civil war, with the aftermath of Aemond’s sorta-assassination of Luke blowing up both sides. This, in turn, gives a sense of propulsion missing from the first season. Now, is it reasonable to wonder if there was a better way to arrive at this place than spending a whole season on exposition? The answer is still yes.

Needing to cover a fair bit of temporal ground, season one also suffered from issues of pacing and scale. Years might pass between episodes, returning to characters who lived through action viewers never got to see and creating an emotional distance the show struggled to overcome. HOTD breezed through Daemon’s marriage with Laena Velaryon, dampening any understanding of what that experience — including the birth of his children — meant to his character. This approach tracks with the source material: George R. R. Martin wrote Fire & Blood as a history text that Sapochnik and Condal opted to adapt somewhat straightforwardly. The intent was probably to emulate something like The Crown, but the final product ended up giving hints of History Channel doc — recitation of events more than dramatic storytelling.

Now firmly anchored to the rising warfare between Teams Black and Green, the second season just flows. Sticking to one point in time has caused House of the Dragon to sit more comfortably in its own skin, with each episode taking its time to settle into the beats, the vibes, and the actual conflict. This time, when Daemon storms off from Rhaenyra’s side, we can immediately follow how his feelings contribute to the stakes at hand.

Remember Ser Harwin Strong? Quit lyin’. The manly maned father of Rhaenyra’s children barely registered as a wisp of a presence in the first season before being summarily disposed of by his feet-loving brother Larys — a casualty of a show haphazardly moving things along. How about the Crabfeeder? The crustacean commando could’ve been a B-plot villain in the mold of the Mountain if only he was given more scene to chew (or even a line to say).

To be sure, not every individual in House of the Dragon’s sprawling cast needs their own arc, but a richly realized fantasy setting is one where even the most secondary of characters reflect the texture of the world. We don’t know much about the full biography of Hot Pie, Westeros’s pastry king, for example, but Game of Thrones still allowed him enough space to come alive within the universe he occupied. The guy got bits! House of the Dragon slowing down means it’s able to savor its own flavors, so each new character who appears — like Alicent’s brother Gwayne, played by the delightfully bitchy Freddie Fox — offers viewers an opportunity to sink further into this world, as opposed to another mechanical receptacle for plot.

The new episodes pay increased attention to the citizens of Westeros outside noble bloodlines. Within the Red Keep sequences, this is reflected with a minor touch of Downton Abbey: While the Targaryens and Hightowers scheme and rage around the Iron Throne, the camera roves across the laboring maids, servants, and guards; outside the castle walls, it lingers a little longer on the downtrodden, the baseborn. Early in the season, when the crown executes a notable swathe of smallfolk, we see how their friends and family respond to the cruelty. This is all presumably set-up for further plot developments down the road, but where such sequences would feel like obvious lampshading in the previous season, it now feels organic to the storytelling. Call it another direct result of House of the Dragon slowing down and engaging in the intimacy of the world it’s depicting.

Gone are the days of needing to squint or rely on closed captions [“birthing sounds”] to make sense of what’s happening. Matching its excessively dour tone, season one favored a visual palette so moody and muted you often couldn’t see a damn thing. This nyctophilia reached its apotheosis in “Driftmark,” where the parallel sequences of Daemon and Rhaenyra coupling and Aemond claiming Vhagar were clearly shot during the day but artificially darkened and passed off as night scenes. Why? Creative decision, apparently. This season, someone on staff mercifully arrived at a different visual direction, because you’ll notice an abundance of candles, natural light sources, as well as more daytime scenes. Thank the Lord of Light, I guess. Being able to actually see things has drastically changed my sense of enjoyment watching the show. (Look, dimly lit television affects you the same way seasonal affective disorder does — we might be talking about virtual sunlight here, but it’s sunlight all the same, you know?) Speaking of enjoyment …

All that natural light is put to good use, with wide shots providing opportunities to savor the work put in by the production-design teams. Particular shout-out to Caroline McCall, who’s leading the costume department this season; the reds, greens, and blues are deeper, and a variety of cuts and textures differentiate the outfits for each character. In the great civil war between Team Black and Team Green, I would’ve given the sartorial edge to the former purely on the basis of Rhaenyra’s gothic ensembles, but Otto Hightower’s doublets are lookin’ fine.

No, seriously! A consistent (and absolutely deserved) complaint of the first season focused on how morose the whole thing was. Everyone was so stoic. Everything looked so dark. Nobody seemed to be having a good time, even on a hunt! Perhaps this is fair given all the reproductive horror and tragic familial infighting baked into the plot. However, the conflicts in Game of Thrones were no Disney Channel material either, yet Jon Snow still found occasions to kick it with his bros at the Wall. Season two of House of the Dragon is a lot more fun both in an overt sense — there are actual gags now, including a particularly endearing introduction to the current lord of Harrenhal — and in subtler ways, too. A pivotal moment of hand-to-hand combat dances the line between pure drama and camp, the camera angles cutting so fast it’s impossible to keep track of who is who. It’s hilarious! Still, the show could stand to be funnier. My kingdom for a Bronn!

There were already hints of a Shakespearean style to the performances on House of the Dragon, with an abundance of grand speeches and theatrical blocking where everyone looks like they’re trying to simulate an oil painting. The new episodes lean into this style — so much so, in fact, that House of the Dragon makes Game of Thrones feel naturalistic in comparison. And you know what? It totally works. Taking place nearly two centuries before the march of the White Walkers, House of the Dragon can be viewed as a period piece within the context of the franchise. Plus, deploying this style lends a fitting gravitas to the proceedings: At its heart, House of the Dragon is telling the story of a tragic monarchistic struggle. You’d want someone on the show to be able to say “Get thee to a nunnery!” and for the line to completely work in context.

Listen, if you’re going to sell me a show premised on the notion of people riding dragons and melting the world down to its studs as they try to kill each other … you better give me people riding dragons and melting the world down to studs. Guess what? As House of the Dragon returns, it’s finally happening. And it pretty much rules.