Photo: Thomas Prior for New York Magazine

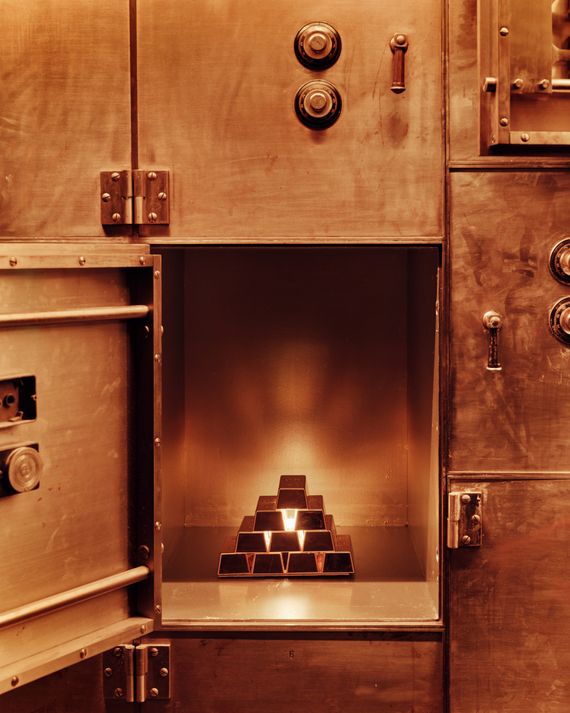

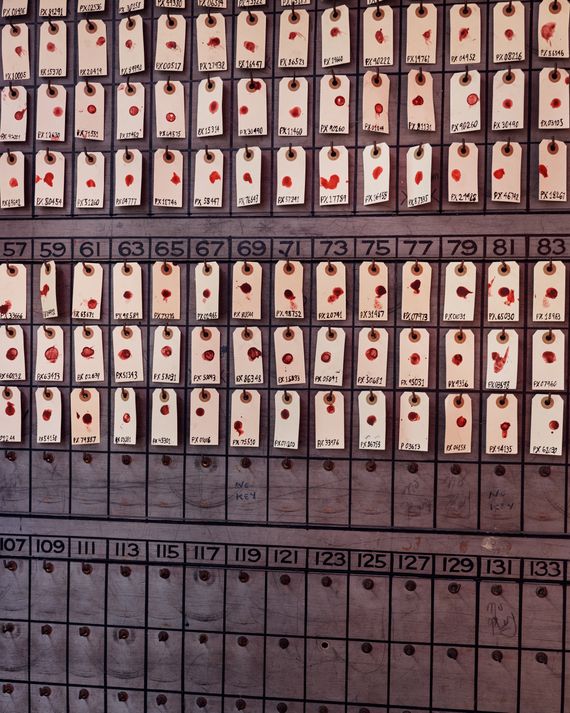

Conwell Coffee Hall opened its doors earlier this year on a narrow, nondescript Fidi street. A giant flag with its logo, a red Devil enjoying a cup of coffee in a letter C with the slogan “The Taste of Success,” stands outside. The former bank (there’s a plaque on the wall sharing the history of banking magnate J. G. Conwell) has been exceptionally maintained and restored, its ornate metalwork and marble columns complemented by rich leather and dark-wood furniture and a sweeping Diego Rivera–style mural. By day, baristas take orders from behind the tellers’ counter, and customers can work on their laptops in cozy nooks or read by the light of imitation-vintage brass banker’s lamps.

But Conwell Coffee Hall is a front. It’s the first set piece in the latest experiential-theater project by Emursive, the production company behind Sleep No More, which has played at the McKittrick Hotel (itself an Emursive fabrication) in Chelsea since 2011. That show, a moody, speakeasy-inspired retelling of Macbeth in a vast, fully explorable multi-floor set, is closing later this year after multiple extensions and 13 years of introducing audiences to immersive theater. “When we started, that word wasn’t in the Zeitgeist,” Emursive partner and co-producer Jonathan Hochwald told me as we sat in Conwell on a Saturday night. To Hochwald, the allure of immersive theater is the ability to disconnect from the outside world and experience “a self-directed dream” with “freedom to choose a nonlinear path.” Few theatrical projects ever mounted have had the scale, scope, budget, and detail of Emursive’s work, and now that Hochwald & Co. are putting Sleep No More to bed, they are hoping to “continue to push the art form forward” with their new show, Life and Trust.

Conwell Coffee Hall’s interior.

Photo: Thomas Prior for New York Magazine

Writer Jon Ronson (The Psychopath Test, Okja) took inspiration from the Faust legend for Life and Trust; look closer at that title and the source text is hidden in plain sight. There are Easter eggs like this all over Conwell: on the plaque, in the mural, and in the menu itself. “The building led to the creation of the story,” Hochwald said. “We were really wanting a New York creation,” and the base of this historic skyscraper, which opened as City Bank–Farmers Trust Company Building in 1931, felt like it was brimming with story. “This was closed off for decades. People who live in the building didn’t even know what was in here,” he told me, motioning around the grand room. It made sense to adapt a tale of a man making a deal with the Devil in a space around the corner from Wall Street in “what was once the heart of global capitalism.” After I spoke with Hochwald, a woman dressed as a bank clerk approached to beckon me down a hallway behind the café, telling me “our esteemed founder, J. G. Conwell, will be hosting a toast for prospective clients in his office.”

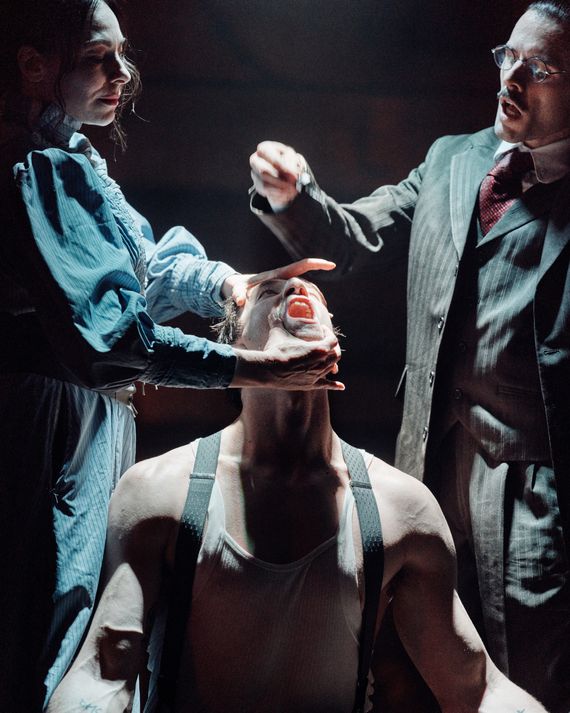

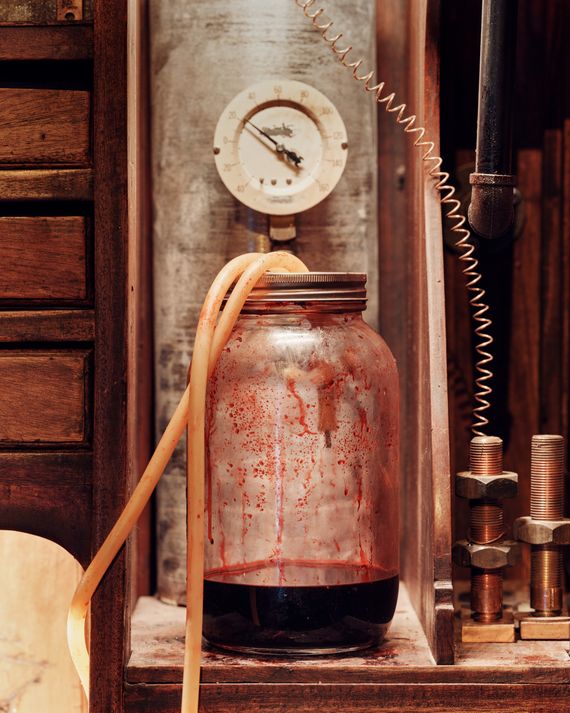

This is how the three-hour experience of Life and Trust begins: a scripted scene (the rest of the show is told through movement) that launches guests down flights upon flights of stairs to explore a story in motion. The details of the story are being kept under wraps, but suffice it to say there are lavish set pieces in a ballroom, an entire carnival, and gardens where the ground feels soft and earthy as you walk through them, as well as intimate moments in apartments, offices, and hidden sanctums. Characters fight, make love, and torture one another (and themselves). There are various shows within the show, ranging from farce to magic to rodeo.

Under direction by Teddy Bergman and co-direction and choreography by The Outsiders choreographers Jeff and Rick Kuperman, the performers move in ways that make full use of the space, timed impeccably to the soundtrack and moving deftly through halls as trails of masked audience members chase behind them like ducklings. The mind struggles to comprehend how Life and Trust can exist in the cramped old confines of historic downtown, where the streets are all narrow and the buildings crowd against one another, where all of Manhattan tapers into a point. Maybe that’s something else immersive theater offers. Wandering farther and farther down the floors, in warm rooms full of bodies moving sweatily, you can easily be convinced you’re in the depths of a particularly fun and debaucherous version of Mephisto’s hell, or at least its sister city, lower Manhattan.

Scenes from Life and Trust, which takes place in more than 100 rooms and features 41 actors in a historic building on Hanover Street.