Photo-Illustration: Maya Robinson/Vulture

This list was first published in 2018 and has been updated to include Asteroid City.

Ranking the films of Wes Anderson feels like a fool’s game, because he’s an auteur’s auteur, with a sensibility so rigorously defined and articulated that you’re either inclined to embrace it fully or reject it completely. He doesn’t do failed experiments or gun-for-hire studio projects or one-offs in a minor key. And though his commercial fortunes have waxed and waned, there’s no evidence that he’s ever cared to fit into the marketplace — or even would know how to do so if he could.

His debut feature, Bottle Rocket, could be called a blueprint of things to come, but beyond that, every moment in his films has been completely thought through and fussed over, which explains why the frame-by-frame arduousness of stop-motion animation was such a good fit for Fantastic Mr. Fox and his superb comedy, Isle of Dogs. Missteps are rare to nonexistent. Every film is exactly as Anderson intended it to be, without the hit-or-miss or ebb-and-flow nature of most directorial careers.

To my mind, Anderson is eleven for eleven, and the separation on the list below is a matter of degrees rather than huge swings in quality between one feature and the next. Any other day, the top seven could shift around a few spots and still feel about right, though Anderson’s best films have layers of emotion and thematic depth that often don’t reveal themselves until two or three or four viewings in, when a small glance or a piece of production design takes on a significance that wasn’t apparent before. Tomorrow the list could be different. In ten years, it could be reversed. Here’s how things stand today:

To a certain extent, The Darjeeling Limited is an unseemly act of spiritual tourism, no better than Eat Pray Love or countless other films about privileged white Americans turning a foreign landscape into the site of their holistic transformation. There’s something perverse about the clash between the unruly sensuality of India and the hermetic quality of a Wes Anderson production, which fetishizes small details, like the complementary pleasures of sweet lime and savory snacks, and casts the locals as mere stepping stones to emotional growth. Yet Anderson, inspired by Technicolor exoticism of Jean Renoir’s The River, understands that he and his characters — three semi-estranged brothers (Owen Wilson, Adrien Brody, and Jason Schwartzman) going through grief and personal setbacks — come to India as outsiders and turn that liability into an asset. The Darjeeling Limited underscores the folly of these men riding the rails with mountains of literal and metaphorical baggage in tow, and how the country humbles them before any healing can begin. It takes some doing for the characters — and for Anderson — to get to the line, “Fuck the itinerary,” and they mean it.

A rough draft by his standards only, Anderson’s first feature includes many of the hallmarks of films to come: brilliant colors and crisply composed frames, whimsical hand-drawn schemes, bold romantic gestures, a brittle camaraderie between outsiders, and a current of melancholy that runs just below the surface. It also established Owen Wilson’s screen persona as Dignan, a dim visionary whose criminal imagination extends to robbing his friend’s house, pulling an after-hours stick-up at a local bookstore, and going “on the lam” with his depressed buddy Anthony (Luke Wilson) and a getaway driver (Robert Musgrave) whose sole qualification for the job is having his own car. Anderson’s twist on the bungling crime picture is hilariously low stakes and inconsequential, but Bottle Rocket has real insight into the feeling of young people cast adrift. While future films would be tighter and more purposeful, none would make room for a beautiful detour like Dignan and Anthony holed up at a motel, where Anthony nurses a wordless bond with a Spanish-speaking maid.

A Wes Anderson parodist couldn’t conceive of a better bit than an homage to the golden age of The New Yorker set at a journalistic outpost in the fictional French city of Ennui. And yet Anderson’s commitment to his sensibility and his craft is folded into this sublime anthology of stories, which honors the finest journalistic tradition of opening a small window into the lives of others — and doing it concisely, too, within a limited word count. Playing like three “Shouts & Murmurs” pieces tied together by a charming wraparound introduction to the paper itself, The French Dispatch follows the love between an imprisoned, half-mad artist (Benicio Del Toro) and his female guard (Léa Seydoux); a student revolutionary (Timothée Chalamet) taking part in riots that evoke May 1968; and a chef profile that morphs into an action-packed crime story. Anderson packs the film so densely with familiar faces and detailed visual information that it can feel both overwhelming and slight on first viewing. A second makes a lovely soufflé.

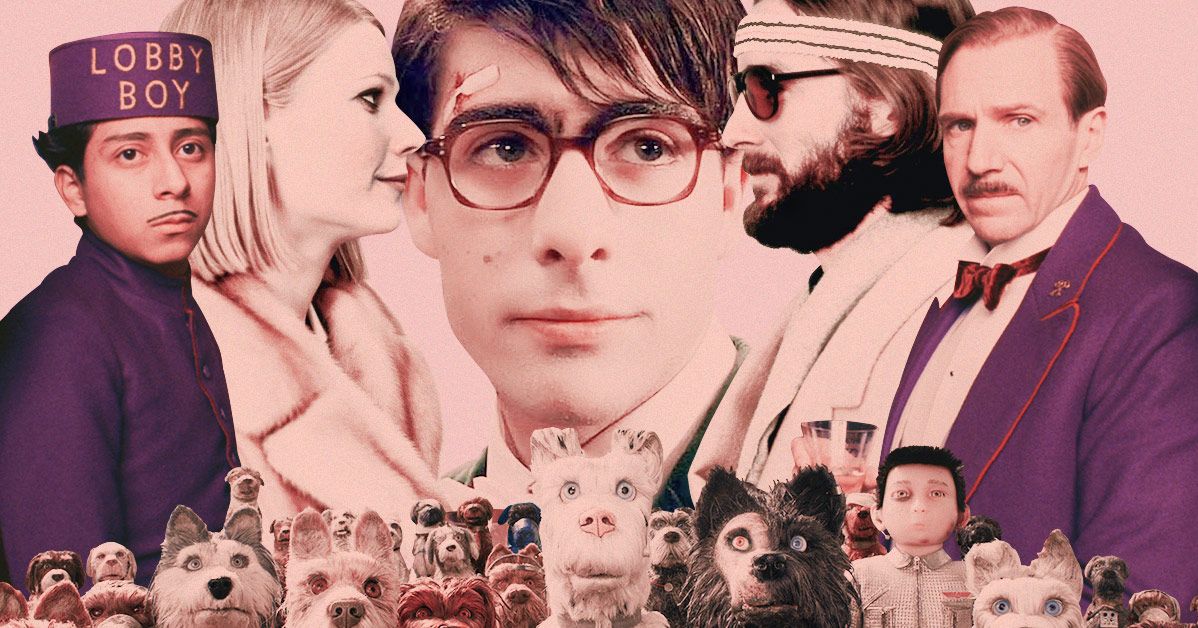

Anderson’s second foray into stop-motion animation may be his most generous and accessible entertainment, which is an odd thing to say about a film darkened by themes of authoritarianism, internment, and extermination. In a dystopian future Japan, a grim-faced demagogue fights a “canine flu” epidemic by quarantining the nation’s dogs on a trash island, where they travel in packs and live off rotten food. The basic plot mirrors Kon Ichikawa’s brutal antiwar classic Fires on the Plain, in which Japanese soldiers are left to starve on the Philippines island of Leyte during the waning days of World War II, and Anderson is serious about political oppression and the power of dissent. But that medicine goes down with a heaping Alpo scoop of sugar: a voice cast bustling with Anderson’s usual players, plus newcomers like Greta Gerwig, Courtney B. Vance, and Yoko Ono; a nonstop fusillade of canine witticisms and antics; and gorgeously rendered figurines and backdrops, which depict Japan in dollhouse miniature. It’s only later that Isle of Dogs reveals itself as a deeper and more troubled film than its abundant surface pleasures suggest.

As Anderson’s career has moved forward, the intricacies and layers of his conceits, characters, and narrative architecture have gotten so dense that his filmography has started to feel like the weekly progression of the New York Times’ crossword puzzle, with Bottle Rocket and Rushmore as the easy-solve Monday and Tuesday and the others getting harder every day. Asteroid City is a movie nested within a televised play and a behind-the-scenes introduction, and its setting, a tiny Southwestern town in the mid-1950s, evokes the mysteries of outer space and the melancholy intimacies of teenage love, adult grief, and family ties found in Anderson films like Moonrise Kingdom and The Royal Tenenbaums. It also has a cast list so long that it must have shut Hollywood down for a month. Yet, Anderson’s evocation of the wonders and anxieties of postwar America add a unique tension to the personal dramas within Asteroid City, and the pointillist beauty invested in this fantasized locale is endlessly pleasurable. The alien encounters in Anderson’s world neither begin nor end with a visitor from the stars.

Torching $50 million in studio money, Anderson turns his affection for Jacques Cousteau’s seafaring adventures into a production as overstuffed as the tiny submersible that carries his ensemble to the bottom of the ocean. As a follow-up to The Royal Tenenbaums, The Life Aquatic feels conspicuously unbalanced, but the sheer abundance of delightful conceits more than makes up for it: a boat with various quirks and amenities, such as a sauna (with a Swedish masseuse on staff), a film-development and editing suite, and two supposedly intelligent dolphins that swim below deck; stop-motion sea creatures; a Brazilian guitarist, Seu Jorge, who performs David Bowie songs in Portuguese; funny bit players like the unpaid interns from the University of North Alaska and the “bond company stooge” onboard to keep costs in line; and run-ins with a well-funded rival crew, led by Jeff Goldblum, and a band of incompetent pirates. Anderson can’t pay off every element satisfactorily, but the climatic scene, which brings Bill Murray’s Zissou and company face-to-face with the “jaguar shark” that took his best friend’s life, is perhaps the most beautiful sequence he’s ever staged.

With a title that evokes the enchanting quality of illustrated YA fantasies — the type of books with busy covers and detailed maps inside — Moonrise Kingdom captures the heightened emotions of first love, when two adolescents are swept along by naïve, unbridled passion. On the fictional East Coast island of New Penzance, a rarified Anderson-ian universe accessible only by ferry, Sam (Jared Gilman) and Suzy (Kara Hayward) run away from scout camp and home, respectively, to create an idyll for themselves by the sea. The two are an odd pair — the boy an orphaned misfit, the girl a sophisticate who carries herself like a French New Wave heroine — but Anderson contrasts the purity of their feelings for each other against the chaos of adults, like Suzy’s parents (Bill Murray and Frances McDormand), or Sam’s troop master (Edward Norton), whose life experience is one of accumulated disappointment and failure. The overall effect is profoundly bittersweet: Young love and adult disillusionment not only coexist in New Penzance, they mingle and create something new.

Anderson’s first (and to-date only) adaptation draws from Roald Dahl’s children’s novel — with additional details from Dahl’s The Champion of the World and the author’s life — but the two sensibilities are so compatible that it’s almost like watching Anderson reveal his own artistic origin story. Fantastic Mr. Fox also marks his first foray into stop-motion animation, which, if anything, better accommodates his handcrafted meticulousness than live action. Though not a traditional kids’ movie by any stretch, there’s still a lot of wonderful Dignan-esque scheming involved in Mr. Fox (George Clooney) stealing from the adjoining farms of Boggis, Bunce, and Bean, and the film has the warmth of an old Rankin-Bass production. Anderson seems like the last person fit to comment on the Herzog-ian theme of civilization and man’s animal nature, but Mr. Fox’s tendency to act on impulse, regardless of the consequences, puts him right in line with Dignan, Max Fischer in Rushmore, Steve Zissou in The Life Aquatic, and Anderson himself, who’s nothing if not a stubborn iconoclast. The main difference is that Anderson probably devours a more refined preparation of squab.

Perched upon a mountaintop in the fictional Eastern European country of Zubrowka, the eponymous structure in The Grand Budapest Hotel stands as a monument to impeccable service and design — and, as such, a monument that Anderson, with all due modesty, has built to himself. Though the hotel’s crumbling edifice in the late ’60s resembles the faded glory of the Tenenbaum house, Anderson flashes back to better days, before World War II and communism chipped away at it. Ralph Fiennes’s concierge is the director’s natural surrogate, the behind-the-scenes guy who tends to every detail of the hotel’s operation while going to extraordinary lengths to please the guests, even if that means bedding octogenarians. The Grand Budapest Hotel is a not only a great film about direction, but about storytelling itself, elegantly stacking a nesting doll of timelines with a cross-country caper, the encroachment of world war, and detours into the secret society of concierges and a stop-motion chase through an abandoned Winter Olympics site. The Life Aquatic struggled to harness such an crowded agenda, but like Fiennes’s Monsieur Gustave, Anderson handles it all with astonishing deftness.

The trick of the title is just a start: We expect to be watching a film about New York City royalty, the type that might have emerged had the three Tenenbaum children (Gwyneth Paltrow, Ben Stiller, Luke Wilson), prodigies all, not peaked early and flamed out. Instead, this is a film about the family of Royal Tenenbaum (Gene Hackman), the grizzled patriarch who abandoned them long ago, leaving a house that sits like a non-curated museum of past glories. Among its many virtues, The Royal Tenenbaums is a testament to Anderson’s economy of style and language: It has enough characters and subplots to accommodate a movie twice its length or more — the IMDb plot synopsis is nine paragraphs and 928 words long — but all the emotions are distilled in single lines or moments out of time. (Multiple viewings are helpful for all of Anderson’s films, but they’re essential here.) His ability to write across the ensemble turns the family into an unforgettable organism, pulsing with sadness and regret and a small, late-breaking surge of scrappy resilience. Perhaps the Tenenbaum name is synonymous with failure, but the film is ultimately a touching affirmation of family and how it can process life’s inevitable disappointments.

Just two years after Bottle Rocket, Anderson made one of the great coming-of-age comedies, borrowing heavily from The Graduate, but upending its story of postcollegiate listlessness to focus on its opposite: a 15-year-old (Jason Schwartzman) with no shortage of confidence and vision, but plenty of room for maturity and growth. Rushmore zips along on Max Fischer’s precociousness — his theatrical stagings of gritty films like Serpico, his involvement and founding of many other extracurricular activities, his courtship of a first-grade teacher (Olivia Williams) twice his age — but Anderson allows him to be callous and flawed, too, swamped by juvenile narcissism and shame over being a poor kid at an elite private school. As Herman Blume, a rich industrialist cocooned in melancholy, Bill Murray opened up another front in his career, drawing on deep reserves of sadness and soul that he had never fully accessed before. There’s not a wasted second in 93 minutes of Rushmore, which feels both purposeful and personal, the product of a Max Fischer type looking back on adolescence with the empathy and wisdom he didn’t have at the time.