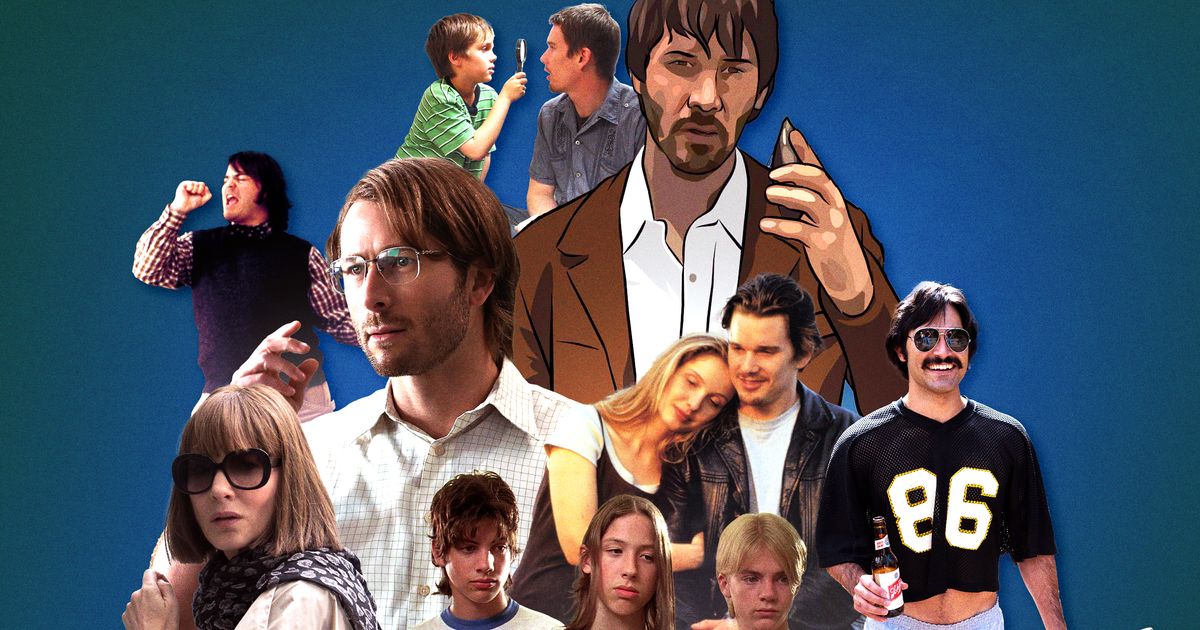

Photo-Illustration: Vulture; Photos: Gramercy Pictures, Everett Collection (Matt Lankes/IFC Films, Warner Independent, Van Redin/Paramount Pictures, Columbia, Matt Lankes/Netflix, Wilson Webb/Annapurna Distribution, Paramount)

This list was originally published on November 1, 2017. It has been updated to include subsequent Richard Linklater films, including Hit Man.

From the moment he picked up an 8mm camera and put himself through DIY film school for $3,000 with It’s Impossible to Learn to Plow by Reading Books in 1988, Richard Linklater has seen the world by way of Austin, Texas — a self-styled outsider whose sensibility is defined by boundless curiosity and wanderlust. Slacker showed the independent world that great films could come from anywhere and in any form, but Linklater has never boxed himself into any one scene, slipping dexterously from micro-indies to major studio projects, and all points and genres in between. At the same time, there are strong connections that unify and enrich his filmography: the philosophical musings of Slacker and Waking Life; the personal memories that illuminate Dazed and Confused and Everybody Wants Some!!; the temporal experimentation of the Before trilogy and Boyhood; and a more general interest in conversation and human consciousness.

Even Linklater’s misfires are compelling. The worst title on this list, Bad News Bears, is solid entertainment, docked mainly because it’s the only Linklater that doesn’t have a reason to exist. The others may fall short of their ambition, but there are always redeeming values, like the strip-mall blight and bitter ennui of SubUrbia, the period obsession of The Newton Boys and Me and Orson Welles, and the offbeat humanity of Where’d You Go, Bernadette. He can deliver a straight-up crowd-pleaser, too, like his new Netflix tall tale, Hit Man. All 23 of his films — 22 features and a documentary — have merit, and the best ones are animated by unmistakable intelligence and emotional generosity. All right, all right, all right, here we go …

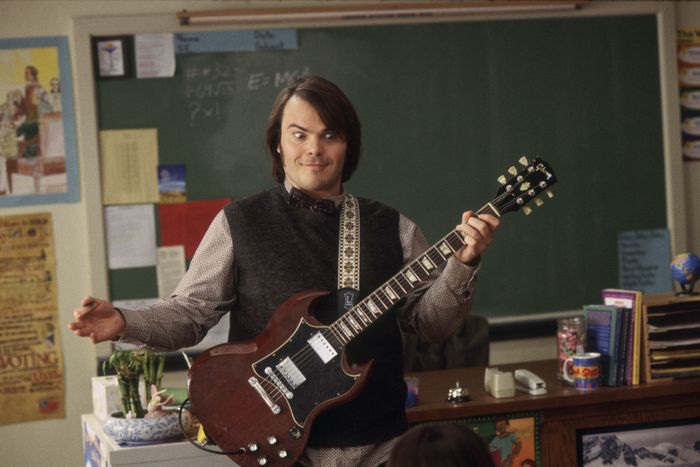

At the time, Bad News Bears was being promoted as a “remix” rather than a remake of the 1976 comedy classic starring Walter Matthau as a raging alcoholic who coaches a little league team populated by delinquents, klutzes, and other pitiable misfits. In truth, the film is the worst kind of remake: unnecessary. Linklater doesn’t add anything to his Bad News Bears that wasn’t present in the original film, so the best he can do is mimic it skillfully, giving Billy Bob Thornton a role as thoroughly in his wheelhouse as Jack Black in School of Rock and hitting all the ornery, underdog-sports-movie beats. Despite Linklater’s personal history as a baseball player — which he would mine to greater effect later in Inning by Inning and Everybody Wants Some!! — he’s never seemed this disengaged.

Financed as part of an initiative to fund ten digital-video features for under $150,000 apiece, Tape remains an unfortunate byproduct of an era where filmmakers were rushing toward a future that hadn’t quite arrived. (See also: Steven Soderbergh’s Full Frontal.) The murkiness of the DV images, combined with the one-room shake-and-bake melodrama, makes the film feel conspicuously half-formed, the equivalent of those low-fi recordings that dominated indie rock in the mid-’90s. But there’s some contemporary resonance to the plot, which kicks into high gear when two old friends (Ethan Hawke and Robert Sean Leonard) of diverging fortunes revisit the time when one of them may have raped the other’s ex-girlfriend. As the drama plays out, the Rashomon effect takes over.

Though Linklater would make a “spiritual sequel” to Dazed and Confused over 20 years later with Everybody Wants Some!!, SubUrbia tastes like the stale backwash swallowed by the kids who never left town after graduation. The big problem with the film, however, is that Linklater didn’t write it, Eric Bogosian did, and the sour, judgmental animus of Bogosian’s voice is fundamentally at odds with Linklater’s more naturalistic vibe. Characters with names like Pony, Sooze, Buff, and Bee Bee sound appropriated from a West Side Story rough draft, each representing a type (the Rock Star, the Veteran, the Performance Artist, the Party Animal) that Bogosian sets crudely into conflict. Still, Linklater directs the hell out of it, adding a terrific indie-rock soundtrack (fittingly dominated by Sonic Youth) and an impression of dreary, strip-mall homogeneity that stands as the film’s most persuasive character.

Photo: Wilson Webb/Annapurna Pictures

One of the more peculiar misfires of Linklater’s career, Where’d You Go, Bernadette seems to have all the elements of a great film: A juicy role for Cate Blanchett as Bernadette Fox, an architect turned agoraphobic recluse and neighborhood terror; a source novel, by Maria Semple, that supplies colorful supporting characters and adventurous narrative detours; and a rich theme about what happens to creative women when their impulses are suppressed. Yet the film is oddly rudderless, a neither-here-nor-there comedy/drama that has much to admire, like Emma Nelson’s performance as Bernadette’s headstrong 15-year-old daughter, but conspicuously little energy to move it forward. Only when its hero visits Antarctica and starts to rediscover her inspiration does the film take off. By then, it’s virtually over.

Turning Eric Schlosser’s muckraking (and stomach-turning) polemic about the fast-food industry into a fiction feature didn’t sound like a promising idea, for reasons Linklater’s adaptation often articulates all too well: The facts and figures that compose a strong argument can’t be translated smoothly into dialogue. At its worst, the film feels like a cross between Robert Altman and the op-ed section, but some of the individual stories are powerful, and Linklater succeeds in establishing a broad link between fast food and a conformist culture where we are what we eat. Like the cattle that don’t move when activists tear down their fences, the film suggests we confine ourselves to borders even when they don’t exist.

As played by Christian McKay, the young Orson Welles of Me and Orson Welles is electrifying, an irrepressible force of nature at only 22, rallying his troupe into pulling off an audacious reading of Julius Caesar at the Mercury Theater in 1937 — still a few years before he’d alter the course of film history with Citizen Kane. It’s the “me” part of the film that’s less inspiring. As an actor plucked from obscurity to play the minor part of Lucius, Zac Efron gives the film an abashed point of view — and, in practical terms, a bankable star in the lead — but his passivity shrinks in the face of McKay’s dynamism. Still, Linklater re-creates the period with the same scrupulousness and particularity he brought to The Newton Boys, and the film surges to life whenever it burrows into the creative process.

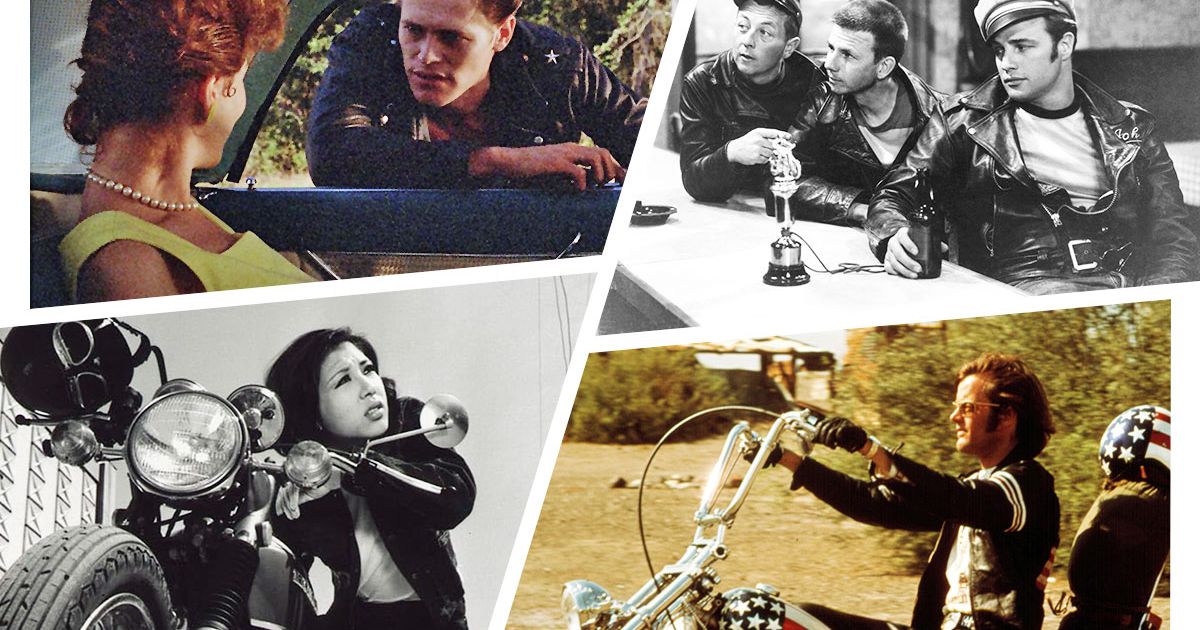

Linklater’s first swing at a major-studio film is considered one of his biggest misses, caught in a dangerous spot between the low-key vibe of other Linklater films and the robustness and bravado expected of a modern genre picture. Yet The Newton Boys is appealing for similar reasons, rejecting both conventional and revisionist Westerns in favor of a knockabout, happy-go-lucky treatment of bank-robbing brothers who are loathe to reach for their guns. (They wouldn’t do it at all if the government didn’t insure the accounts.) Casting Matthew McConaughey, Ethan Hawke, Skeet Ulrich, and Vincent D’Onofrio in the lead roles, Linklater follows the brothers’ audacious nighttime raids, which involve blowing safes with nitroglycerin, but he’s just as content to bask in period bric-a-brac and enjoy their tomcatting and roughhousing off the clock.

Photo: Lionsgate

Linklater’s sequel of sorts to the 1973 classic The Last Detail is uncharacteristically down the middle, even corny, in its depiction of three former Marines and Vietnam veterans (Steve Carell, Bryan Cranston, and Laurence Fishburne) who reunite after one of them loses his son in the Iraq War. Yet Last Flag Flying gains in depth and emotional richness as it goes on and uncomfortable truths start to muddy the official story about what happened. At a time when military service and the national anthem have become heavily politicized, the film reflects powerfully on the meaning of patriotism and how sacrifice is framed by the country and those who serve it. By connecting Vietnam and Iraq, too, Linklater expresses the universality of war and the crushing deceptions involved in waging it.

For Linklater’s only feature documentary, the universe conspired to bring Augie Garrido, the winningest baseball coach in NCAA Division I history, to his hometown school, the University of Texas, for the last two decades of his career, which ended with 1,975 wins. Far from the stereotype of a raging taskmaster, Garrido instead focuses on the minutiae of the game and waxes philosophical about winning and losing, to the point where he could easily get cast in the next Slacker or Waking Life. Produced for ESPN, Inning by Inning isn’t the typical cookie-cutter sports doc, but a thoughtful rumination on sports and life, including the inevitability of failure. Despite all his wins, Garrido notes that even the best baseball player gets an out most of the time — it’s how you process it that counts.

Shot in Super 8mm on a $3,000 budget, Linklater’s first feature stands as a symbolic rebuke of the film-school brats of New Hollywood, making the implicit argument for skipping class and learning how to make movies on the fly. Casting himself as a lonely wanderer who stumbles around Austin and makes his way, via hitchhiking or the rails, to far-flung places like Missoula and San Francisco, Linklater makes a travelogue about his own feelings of curiosity, restlessness, and existential uncertainty. There are aspects of It’s Impossible to Learn to Plow by Reading Books that would never resurface, like its minimal dialogue and long, static takes, but it’s the raw clay from which he molded a career, a statement of purpose from a young artist with an adventurous spirit.

Many prominent science-fiction films have been inspired by Philip K. Dick stories (Blade Runner, Minority Report, Total Recall, etc.), but few have ventured to adapt them in the truest sense, because the paranoia and terror that runs through them is so internalized and difficult to represent visually. Linklater solves these problems through a slicker version of the rotoscope-animation process behind Waking Life, here applied to the creeping schizophrenia of an undercover cop (Keanu Reeves) plagued by the same synthetic drug he’s investigating. Released the same year as Fast Food Nation, A Scanner Darkly airs similar concerns about corporatization, but the animation, with its trippy “scramble suits” and hallucinations, makes them far more visually persuasive.

Memory and fantasy intermingle beautifully in Linklater’s sweet and sneakily profound reverie about growing up in NASA country. Using a less janky version of the Rotoscoping style of Waking Life and A Scanner Darkly, the animation allows for literal flights of fancy while staying grounded in the period. Jack Black narrates the perspective of a man looking back on his boyhood in 1969 Houston, when he was a 10-year-old who got the opportunity to go to space due to NASA building too small a capsule and seeking an untrained kid with middling grades. Linklater evokes the time in incredible and often hilarious detail, but he finds perspective on a historic moment when the country was changing in ways a suburban white kid couldn’t fully grasp.

Photo: Netflix

By drawing on another Texas Monthly piece by Skip Hollandsworth, the author of the true story that inspired Bernie (see below), Linklater has made the ideal companion piece, again building a vehicle around the specific talents of his lead actor and embellishing a wildly entertaining Lone Star tale about the elasticity of identity. Here, Glen Powell (who also co-scripted) stars as a mild-mannered philosophy professor whose part-time tech gig for the New Orleans Police Department takes a turn when he starts posing in various guises as a hit man to entrap people who want his services. As he thrives in this undercover role and enters into a relationship with a woman (Adria Arjona) who wants her abusive husband dead, Hit Man morphs into a sexy, twisty (and, at this point, wholly fictionalized) neo-noir comedy that plays like a modern-day Double Indemnity.

It would have been easy for Linklater, Hawke, and Julie Delpy to put Jesse and Céline on another swooning walk-and-talk against a picturesque European backdrop, in this case, the Gulf of Messenia in Greece. But as Before Midnight opens, Céline and Jesse have committed to each other as a couple and as parents to twin girls, which means their time together has extended from less than a day total to several years and their relationship has shifted from theoretical to real. In Before Sunrise and Before Sunset, their conversations would occasionally get contentious, which is natural for two smart, opinionated people, but Before Midnight makes contentiousness their primary mode. The love between them is still piercingly evident, but they’re no longer moony romantics, separated by time and distance. They have shit to work out.

A decade after Slacker, Linklater returned with another loosely connected series of philosophical musings and blackout sketches, but used emerging technology to lure viewers into an altered state of consciousness. With digital video on the rise, Linklater deployed rotoscoping maestro Bob Sabiston and his team to animate over the images, which creates an effect that’s deliberately shimmery and destabilizing, like the fuzzy edges of a dream. Truth be told, some of the monologues in Waking Life, like academic lectures on existentialism and “post-humanity” or on the film theory of André Bazin, would be hard to tolerate without the hypnotic inducement of the animation. But the dreamlike context opens up the mind to many ideas, like the possibility that the rage-fueled fantasies of Alex Jones may one day swallow a nation.

Adapting the Texas Monthly article “Midnight in the Garden of East Texas,” Bernie is the rare stranger-than-fiction true-crime story where there’s no mystery about what happened: Bernhardt Tiede, a 39-year-old assistant funeral director in Carthage, Texas, shot and killed his frequent companion, 81-year-old millionaire widow Marjorie Nugent. What makes the story interesting is how the people of Carthage refused to believe he did it — and if he did, the mean old woman deserved it anyway. Linklater approaches Bernie with a perfectly deft bemusement over an absurd situation, ingeniously rendering the townspeople as a Greek chorus of talking heads and handing the rest over to Jack Black and Shirley MacLaine, who share a frisky comic energy. Beneath all the fun is a disturbing and all-too-relevant commentary on human nature: We see what we want to believe and discard all evidence to the contrary.

With Blake Jenner’s Jake filling in for Jason London’s Randall “Pink” Floyd as the Linklater surrogate — a jock who’s into nerd stuff, too, basically — Everybody Wants Some!! graduates the slice-of-life nostalgia of Dazed and Confused from high school to college, where the fun is less mitigated by growing pains. Set over a weekend in 1980, Everybody Wants Some!! is a frat-house comedy about ballplayers drinking and carousing in the days leading up the responsibilities of practice and school, but Linklater isn’t the Animal House type. Instead he’s made a memory piece that’s loaded with dumb masculine rituals, eccentric characters, a kick-ass soundtrack, and the same gentle curiosity that’s always set Linklater apart.

Photo: Andrew Schwartz/Paramount Pictures

Linklater hasn’t always seemed comfortable making studio films — indeed, producer Scott Rudin had to talk him into directing this one — but School of Rock threads the needle beautifully between Linklater’s slacker iconoclasm and immensely satisfying general-audiences entertainment. Here and later, in Bernie, he also gets the best out of Jack Black, whose Tenacious D persona (disheveled devotee of baroque classic rock) gets filtered through the role of a phony substitute teacher who uses the musical talents of precocious private-schoolers to form a new band. For as much as Linklater and Black poke fun at rock pomposity — in professorial mode, Black devotes a chunk of the day to “rock appreciation and theory” — the film is a joyous celebration of youthful rebellion, artistic collaboration, and big, irresistible hooks.

Before the story of Céline (Julie Delpy) and Jesse (Ethan Hawke) would be continued in two unexpected — and unexpectedly wonderful — sequels, it was this perfect little romance, a connection between two strangers that burns brightly through the night and is extinguished by the dawn. For the short time that Jesse, an American tourist, and Céline, a Frenchwoman heading back to Paris, disembark a train for an evening in Vienna, they fall for each other with the heedlessness of young people living in the moment. With the city serving as an enchanting backdrop — in one beautiful montage, the places they visit are given new significance by them having passed through them — Before Sunrise has the conversational feel of an Eric Rohmer film, but runs hot with genuine emotion.

It’s no overstatement to say that Linklater’s breakthrough changed the face of American independent filmmaking — where a film could come from, what it could be about, and how it could be about it. Starting with the director himself in a taxicab, musing to a hilariously affectless driver about his dreams and about choices spinning off into their own alternate realities, Slacker drifts off into a half-profound, half-absurd roundelay of vignettes with no connective tissue beyond Linklater’s inquisitive camera. Before “Keep Austin Weird” was emblazoned on T-shirts at the airport, the film captured its authentic essence, with conspiracy theorists, dime-store philosophers, and one Madonna-pap-smear saleswoman given the floor.

Time has always been a powerful weapon in Linklater’s arsenal, whether it’s narrowed to the all-nighters in Dazed and Confused and SubUrbia, or expanded over nine-year intervals, like Céline and Jesse’s relationship in the Before trilogy. Boyhood is a one-of-a-kind temporal experiment, tracking the development of young Mason Jr. (and the child who plays him, Ellar Coltrane) from age 6 to 18, as he goes through the various stages of his life and the culture changes along with him. Linklater watches his mother (Patricia Arquette) bounce around from one bad relationship to the next, moving them from different homes and cities along the way, and deals with a father (Ethan Hawke) who’s an inconsistent presence in his life. But amid that scripted drama, there are the more spontaneous wonders that come with getting older and developing interests, and the unique phenomenon of watching the years pass before our eyes. Kids grow up fast, the expression goes — Boyhood literalizes that to heartrending effect.

Photo: Album/Alamy Stock Photo

Before Sunrise ended on such an exquisite will-they-or-won’t-they question that answering it seemed like a terrible mistake. Yet Before Sunset is the best film of the trilogy, seizing on the regret Céline and Jesse feel over the life they could have had together and the romantic possibility that their story together isn’t over yet. It turns out that the two didn’t reunite a year after the events of Before Sunrise, so they’re seeing each other again for the first time in nearly ten years, as Jesse whisks through Paris on a book tour. Unfolding in the brief time before Jesse has to catch a flight back to America, their conversation picks up the same easy, thoughtful, occasionally contentious flow, but with the added weight of regret over where their adult lives have led them. The ending, another open question that would be answered by the next sequel, is as crystalline a moment as any in Linklater’s filmography.

Drawn from Linklater’s own memories of high school circa 1976, Dazed and Confused catches its characters at an awkward period of transition, when they’re either just entering high school or looking forward to their senior year and whatever scary destination lies ahead. Linklater intended it as a bittersweet memory of teenage rites and rituals, but the film instead grew into a stoner classic, an immersive hang-out comedy that evokes the music, fashion, and sentiment of the period and sustains a dusk-’til-dawn buzz of beer kegs and weed. Not only does Dazed and Confused have unusual rewatch value, it can be rewatched in different ways: as background noise at a party, easy to engage with casually like dropping into a conversation; as a clip reel of favorite scenes, like Matthew McConaughey’s career-making turn as a skeevy townie still making the scene; and as a film that rewards close study with a complex, personal reflection on adolescence.