On the Shelf

Home and Alone

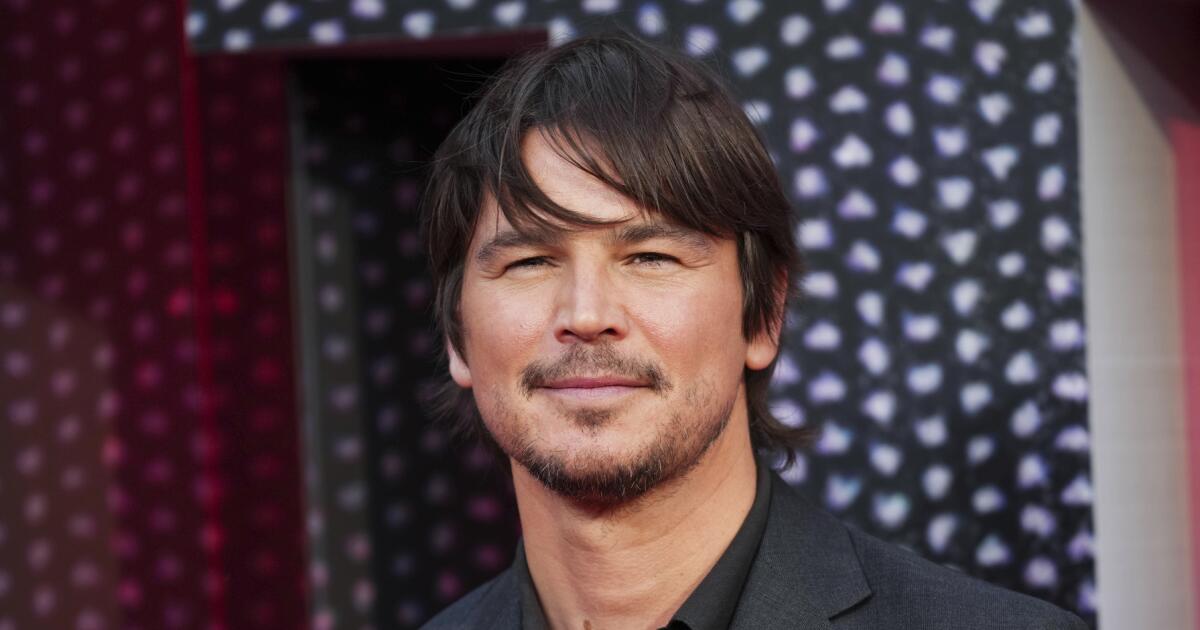

By Daniel Stern

Viva Editions: 314 pages, $24

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Daniel Stern is best known as one-half of the Wet, and later Sticky, Bandits who plague Macaulay Culkin’s Kevin McCallister in ’90s Christmas staples “Home Alone” and “Home Alone 2: Lost in New York.” But he almost wasn’t cast in the role of Marv, the gangly, bumbling sidekick to Joe Pesci’s Harry. After a change in schedule meant the six-week shoot that Stern had signed on for was upped to two months but the pay remained the same, he “made one of the stupidest decisions in my showbusiness life” and backed out of the deal. Someone else got the role but, after a couple of days of rehearsals, producers wanted him back and deferred to the original contract.

It’s a recurring theme throughout Stern’s career and his memoir, the aptly titled “Home and Alone,” which publishes Tuesday. “I almost blew it a couple [more] times,” he tells The Times via Zoom from his farm in Ventura. They are: 1991’s “City Slickers,” in which Stern replaced Rick Moranis, who then returned to the movie before leaving again, and “The Wonder Years,” the pilot of which premiered without Stern’s voice-over after he was unceremoniously fired and — you guessed it — brought back to narrate the rest of its six-season run.

Stern also held out for a bigger payday on “Home Alone 2” when he found out he wasn’t getting as much as his co-leads, but ultimately signed on to the sequel. “There’s lots of things I get out of the movies besides money,” Stern says.

“Home and Alone” by Daniel Stern

“Home and Alone” is a refreshing glimpse into the life of a fairly well-known character actor who’s hit it big in the aforementioned parts but who seems to get the most fulfillment out of his roles off-camera, including as a director, sculptor, father and philanthropist. The latter earned him the President’s Call to Service Award from Barack Obama for his charity work with young people, particularly the Boys and Girls Clubs of America, which proceeds from the sale of “Home and Alone” will benefit.

“What surprised me about writing the book was that a theme came to me which I didn’t expect, and that was empowering young people,” Stern says.

It’s no surprise that most of his work centers on this. “In showbusiness, it’s almost a lose-lose for child actors. If they’re going to be in showbiz, they should be in a movie with me! It’s my fatherly instinct to help the kids through it,” says Stern, who had children in his early 20s while he navigated Hollywood.

It’s a journey in which he’s worked alongside many of the industry’s biggest players, from Glenn Close in one of his first plays to director Robert Redford, who gave Stern the best advice of his career — knowing which lens the director is filming with in order to cater the performance to it — which no doubt informed Stern’s performance in, as he calls it, the “live action cartoon” “Home Alone.”

It’s also one in which Stern has encountered some of the industry’s biggest abusers too, including on the 1999 sitcom “Partners” with CBS president Leslie Moonves, director Brett Ratner and star Jeremy Piven, all of whom Stern calls out in the book for harassing women, who confided in Stern, on the set.

But what about those he doesn’t? One of Stern’s best friends was Mel Gibson, and he’s working on a musical adaptation of his 1984 movie “C.H.U.D.” with CeeLo Green, who was accused of sexual battery in 2012. (The Los Angeles County District Attorney’s Office declined to press charges.)

“It’s how the people and the stories hit me,” Stern offers, adding that he’s wary of speaking for others. “Just tell your story. I want other people to tell their stories. Everybody can.”

That’s what he primarily sees himself as: a storyteller.

“As an actor, I love playing my part, but in a movie, the director tells the story. As I’ve grown, I like to tell the story,” whether that be directing, screen- and playwriting or sculpting — his creations litter the background of his workshop where he takes the video call. He still accepts the odd acting job here and there, as with Season 4 of “For All Mankind,” which is likely the last we’ll see of Stern on the show, which has a penchant for turning over its cast amid time jumps between seasons. “It was a great job. I love the show, but I had to leave my house much too much,” Stern chuckles.

When he does, he’s usually met with regalement about what Marv means to a generation of people — this writer included. “How many people in the world are stopped by perfect strangers who tell them, ‘I love you. My family loves you. You bring us joy. You are a part of our family holiday tradition,’ and all of the other wonderful things people say to me all the time?” Stern ponders with fondness in the book.

Macaulay Culkin and Joe Pesci in “Home Alone.”

(TNS)

We end our conversation with the age-old question: “Home Alone” or “Home Alone 2”? “Which of my children do I love more?!” he laughs. He’s seen each only once; he doesn’t like to watch his own work. Stern acknowledges that although the original is “embedded in people’s hearts” and it might be “sacrilegious” to say “Home Alone 2,” “the filming of that one is the winner.”

The crew, who knew each other from the first movie, delighted in taking turns throwing foam bricks off the roof of a dilapidated New York City brownstone in the middle of the night. In another iconic scene in said brownstone, Stern’s Marv is electrocuted. Stern gave his all in the first take, which seemed to go on forever. “I had nothing more I could do, and I still didn’t hear ‘Cut!,’” he writes, because director Chris Columbus and the rest of the crew were laughing so hard they couldn’t find their words.

“I’ve never felt so free to make an idiot of myself on purpose [than in ‘Home Alone 2’],” Stern says. “I was so funny in that moment that I made the director fall on the floor laughing. It’s hard to top that as the stellar moment of my artistic journey.”