It would be difficult to think about two far more divergent personalities than heavyweight champion Muhammad Ali and Hollywood comedian Stepin Fetchit. Temperamental opposites, they fashioned an improbable alliance when Ali was about to make very good on his declare of getting the finest of all time and Fetchit, a previous movie star, was remaining known as out by civil rights leaders for the way his onscreen figures perpetuated racial stereotypes.

Their friendship is the basis of Will Power’s “Fetch Clay, Make Guy,” which experienced its premiere at Princeton’s McCarter Theatre Centre in 2010. A analyze in contrasts, the play broadens our knowledge of these cultural figures, inspecting them versus the backdrop of their different histories and difficult our assumptions about what empowerment looks like.

“Fetch Clay, Make Guy,” which opened at the Kirk Douglas Theatre on Sunday, meanders. The play lacks the structural compression required to build an illusion of dramatic inevitability. But the work attains an impressive electric power in effectiveness.

Vitality is found not in the plot but in the clash of theatrical variations of the two key people. The sales opportunities are amazing. Ray Fisher incarnates, with organic majesty, the brawn and bravado of Muhammad Ali Edwin Lee Gibson shambles and stammers as Stepin Fetchit even though retaining the dignity of a canny survivor.

Below the nimble route of Debbie Allen, the actors endow “Fetch Clay, Make Man,” generated in affiliation with the SpringHill Business, with a flesh-and-bones real truth that transcends the script. The forged, which consists of a knockout performance from Alexis Floyd as Sonji Clay, Ali’s spouse at the time, extends and improves the tale as a result of the movement and method of the figures. (Scenic designer Sibyl Wickersheimer’s format is obscure besides for Ali’s dressing area, but the ensemble is given a lot of place to maneuver.)

College students of performing — or just any individual who admires the art type — must rush to the Douglas to marvel at the eloquence of Gibson’s nonverbal effectiveness. He is just as adept when dialogue is involved, but he communicates Fetchit’s whole historical past in his apologetic posture on your own.

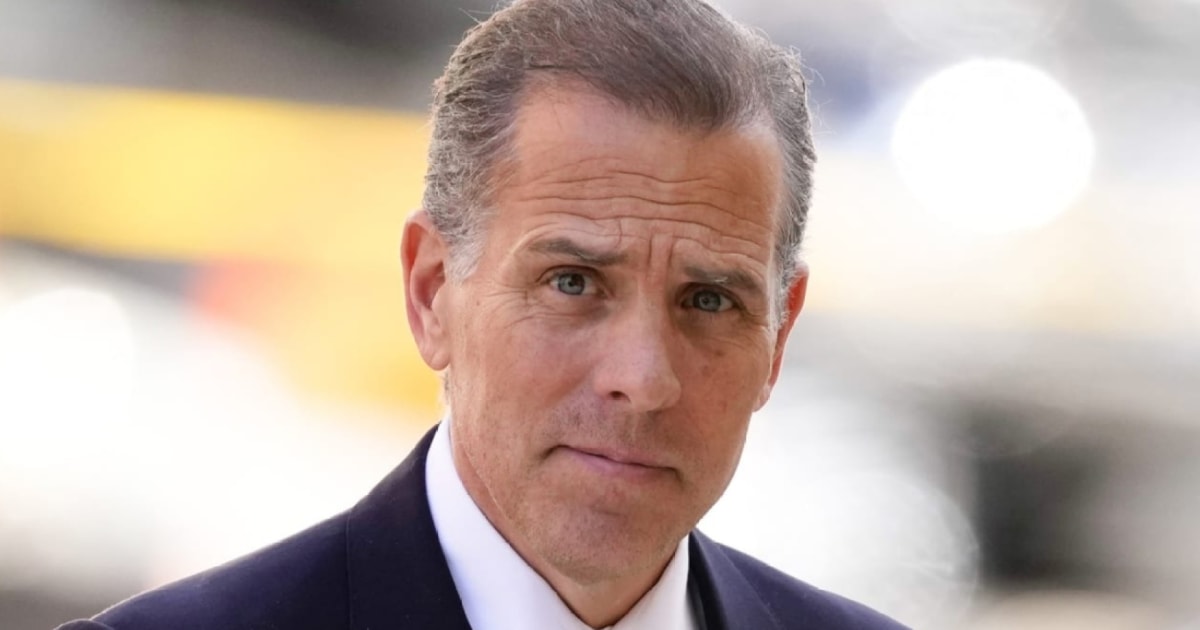

Ray Fisher, remaining, and Edwin Lee Gibson in “Fetch Clay, Make Man” at Heart Theatre Group’s Kirk Douglas Theatre.

(Craig Schwartz)

If Fisher’s charismatic Ali is an exclamation position, Gibson’s Fetchit is a concern mark. Well-known for participating in feckless, servile clowns in the 1930s, Fetchit took on the function of the white man’s idiot onscreen, on the issue that he be formally credited, decently compensated and in handle of the extras in his deal. Dismissed in the mid-1960s as an uncomfortable anachronism, he bobs and weaves in his own way as well as Ali. Rapid to beat a retreat when confronted but prepared to test new floor when the option arises, Gibson’s Fetchit brilliantly embodies the outrageous-as-a-fox interpretation of the character that Ability innovations.

Renowned for his lyrical flair, Ali savors the text that trip off his tongue. Drawing breath for speech looks to intoxicate him. Fisher beautifully inhabits Ali’s bodily grace.

Comprehensive of jovial bluster, Fisher’s Ali occasionally breaks his facade to expose pangs of empathy and twinges of insecurity. It is a complicated time period for the boxing hero. The calendar year is 1965, and he’s gearing up for a rematch with Sonny Liston, whom a 12 months earlier Ali (then Cassius Clay) defeated to develop into Environment Heavyweight Champion. He’s anticipating a a lot more organized and identified opponent this time close to.

Ali, who lately converted to the Country of Islam, is punctilious about matters of faith. He reprimands Sonji when she switches back again into secular garb, but he bristles when his right-hand gentleman, Brother Rashid (a commanding Wilkie Ferguson III), attempts to command him with religious strictures.

Issue is growing over the boxing champ’s basic safety. The murder of Malcolm X has unleashed threats against Ali’s daily life. Ali performs it interesting, never giving away exactly what he’s pondering, but he’s aware of potential risks on several fronts.

Brother Rashid are not able to fathom why Ali has summoned Fetchit, a Hollywood relic whose comedian roles traded on offensive stereotypes. But Ali suspects that Fetchit, who was pals with Jack Johnson, the initial Black Globe Heavyweight Champion, understands the secret of Johnson’s “Anchor Punch.” There are no lengths to which Ali won’t go to turn out to be invincible.

Thankfully, the odd pair connection that develops transcends the “Anchor Punch” tale line, which culminates in a mystical minute that evokes the Middle Passage scene in August Wilson’s “Gem of the Ocean.” Power doesn’t generate this shifting of theatrical gears. Before flashbacks involving Fetchit and Fox Studio boss William Fox (Bruce Nozick) give critical context for understanding Fetchit but likely could have been exchanged for some speedy exposition.

It’s a pity that extra time wasn’t devoted to Floyd’s Sonji, who is warned by Fetchit about the threats of sporting a mask as well long. (Born Lincoln Perry, he shares with Sonji that he fundamentally misplaced that id by taking part in the function of Fetchit far too properly.) Sonji retains annoying Brother Rashid by calling her husband Cassius. Ali does not value it both. Like his new pal, he has experienced to remake himself. How else can he conquer the white gentleman at his own sport?

Winning, nonetheless, exacts a staggering own price tag. This stark truth is created painfully true in the flashes of regret that cross Ali’s deal with and in the occasional bursts of defiant self-assertion that Fetchit, to his credit, doesn’t always wander again.

‘Fetch Clay, Make Man’

Where by: Kirk Douglas Theatre, 9820 Washington Blvd., Culver City

When: 8 p.m. Tuesdays-Fridays, 2 and 8 p.m. Saturdays, 1 and 6:30 p.m. Sundays. Ends July 18. (Simply call for exceptions.)

Cost: $30-$79 (subject to change)

Jogging time: 2 hrs, 15 minutes, with a person intermission

Data: (213) 628-2772, centertheatregroup.org

COVID protocol: Check centertheatregroup.org/protection for latest and up to date data.