This story is part of Image’s May issue, Homemaking, about home and the many ways we choose to make it.

Catherine Opie is excited to talk about her “big-bottom girl chair.” It’s her favorite object in the world that she owns: a black leather chair from Danish designer Finn Juhl. “I knew immediately that it would be the chair where I would do ‘Self-Portrait/Nursing,’” she tells me, referring to her famous 2004 photograph of her nursing her son, Oliver. It’s a queering of the Madonna and Child; Opie, a lesbian who was in the leather community, reveals her right arm adorned with tattoos, the word “Pervert” faintly seen and scarred over her chest. The black chair holds both of their bodies, Oliver’s blond head tilted back on the arm rest. The chair’s name, the Chieftain, feels apt here, as Opie appears calm, regal and in control.

We’re in Opie’s studio in Lincoln Heights as she sits on the chair with her leg swung over one of the arms. She says it’s a chair that can comfortably fit her body. She suggests we try “an experiment” by switching chairs. I’m sitting in the Bhuta chair by the same designer. “Look at how I fill the chair entirely,” she says after we make the switch. The Chieftain, on the other hand, makes her feel like “a proper size.“ “It’s a sexy big-bottom chair!” she says emphatically. “It’s not like shopping at the Macy’s women’s department for over-sized clothing. We’re talking proper design that is beautifully done.” We switch back.

“My work is different from my personality, and I’ve always been curious about that.”

— Catherine Opie

Opie is charming and funny and she appears to know it. “I’m a triple Aries,” she says with pride, sensing that it might startle me. “My work is different from my personality, and I’ve always been curious about that.” Her students, she says, were surprised to find that she had a sense of humor. (Opie taught at UCLA for 25 years and was the chair of the art department before she retired last year.) Hanging on the wall behind her are some of her latest prints: close-ups of blood images in the Vatican’s art collection. An arrow piercing a stomach. The bloody hole in Christ’s foot. A finger digging into a dripping slit across a chest. Opie is performing one of her best talents: taking an iconic subject and making it strange, as she did when she portrayed Niagara Falls out of focus, football players as tender souls, and L.A. highways emptied of cars.

“I put Martin Scorsese in that chair that you’re sitting [in],” she says to me. “And he looked too little in that chair. He complained about it.” Opie found another chair for him from her vast collection scattered about the studio. Scorsese is 5-foot-4; I’m half an inch shorter. I feel comfortable.

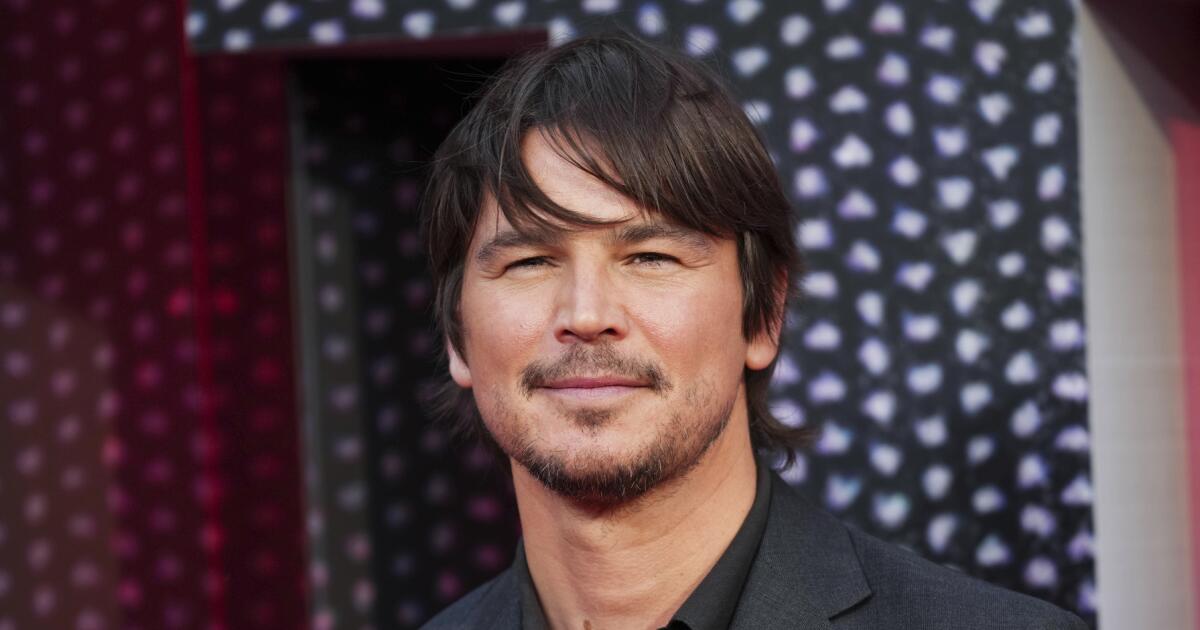

Catherine Opie, “Joaquin,” 2014. (Catherine Opie, Courtesy of Regen Projects, Los Angeles and Lehmann Maupin, New York, Hong Kong and Seoul.)

“Betye (Sitting),” 2019. (Catherine Opie; Regen Projects, Los Angeles and Lehmann Maupin, New York, Hong Kong and Seoul)

“Chairs are everything to me,” Opie says. She uses them for most of her portraits. The only rule is that the chair “can’t be generic.” She introduces me to her cast of characters: the chair with the spindles, the one that pitches the body just so, and the stool that she’s used for portraits since 1990 — that one split apart and she had to glue it back together. She especially loves the kids’ chairs and photographing children in the same chair as they grow, “to see a body change with a piece of furniture.”

In a sense Opie does traditional portrait sittings, where the subject sits patiently still for the photographer. The chairs aren’t always visible in the portraits, but when they are, they bring out the everyday in a person, some familiar gesture, like artist Betye Saar, light and alert on the edge of her seat, or the performance artist Pig Pen casually resting their foot on the second level of a stool or actor and filmmaker Jodie Foster sharply leaning out of her chair, ready to spring off it. The chair becomes another frame, a suggestion of what a person is like.

Catherine Opie’s Finn Juhl Chieftain chair.

Opie got her Chieftain chair in exchange for one of her photographs. She knew it was a “big ask,” given how rare and valuable the chair is. (It’s going for $18,000 at Design Within Reach.) But she says, “I love to barter.” It’s not the only furniture deal she’s negotiated. While I’m at her studio, she receives a Danish couch from a recent exchange. “Are you Danish?” the movers ask. No, she just likes Danish furniture. She asks them to place the couch “underneath the pope.” The pope? They look around the room in confusion. “Yeah, the pope! He’s right there.” She points to her photograph of Pope Francis, barely visible, giving his weekly address from a balcony at the Vatican. The couch is long, yellow and fuzzy; Opie calls it “fish-stick couch.”

Opie has been in the process of buying and moving around furniture since she moved out of the house that she shared with her wife of 20 years. Around two years ago, they initiated a divorce. “There were so many objects I had to say goodbye to,” Opie says sadly and matter-of-factly. “I get attached to objects.” She left most things behind — she left with just one suitcase — but she took the Chieftain with her. It’s been in her studio, where, up until a few months ago, she was living. She hated living here, not having a division between her personal life and work, and it wasn’t until the beginning of this year that she bought an apartment in Hollywood that she’s in the process of renovating.

“Home is complicated for me right now. I know I can make home, and so I’m making a home again. I’m in the process of making home.”

— Catherine Opie

“Home is complicated for me right now,” Opie says. “I know I can make home, and so I’m making a home again. I’m in the process of making home.”

The allure of home has long been at the center of Opie’s work. Her first photo project, at 9 years old, was a series of family album-style photographs. As a young adult, she yearned for “a successful domestic relationship,” a desire that manifested in her 1993 photo “Self-Portrait/Cutting,” when Opie had a friend cut her back with a razor blade and carve the bleeding image of a house and two stick figures. She made the work in the aftermath of a painful breakup, convinced that this domestic dream was unattainable. Between 1995 and ‘98, Opie made the series “Domestic,” traveling around the country and photographing lesbian couples and families in their homes, a monument to queer love. Three years later, she was married and gave birth to Oliver.

It seems that Opie, now 63, has lived out her domestic dream. She doesn’t need it anymore. “For the first time, weirdly, I’m choosing home and decorating it only for me without the aspiration of hoping for domesticity or family,” she tells me. “The longing is no longer there.”

In figuring out what home might look like now, she is throwing herself into her apartment redesign. She’s going for a “midcentury-esque Italian vibe,” with colorful blocks of tile — “elegant, but comfortable and homey. Not overly elegant.” Her girlfriend, an architect, is leading the renovation. Opie is excited to live in an apartment up high; it’s the closest she’ll ever get to her fantasy of living in the hills of the Sheats-Goldstein House, which in 2017 she made a video of, imagining burning it down, her ultimate domestic paradise finally dissolved and out of reach.

“There’s probably a frustrated architect in me,” Opie says. I ask her if she ever thought of becoming one. She might have, but she thought she had to be good at math. Actually she was going to be a kindergarten teacher, but then her stepmom stepped in and asked, “Do you really want to be stuck in those little chairs for the rest of your life?” Opie points to one of her tiny children’s chairs and proceeds to sit in it. She’s playing musical chairs again, before sitting back in her beloved Chieftain, which, she says, is destined for her new Hollywood home.

Catherine Opie in her Finn Juhl Chieftain chair.

In February, I go to Opie’s career-spanning exhibition at Regen Projects, her gallery of 30 years. None of the photos have been shown before; they’re all outtakes, the works that happened along the edges and remained in the archive. The 6th Street Viaduct under construction. The digging up of the Westlake/MacArthur Park subway station in 1989. One of Opie’s girlfriends shaving in the tub. A blurry shot of Club F—, the space dense with bodies under the strobe lights.

When I think of Opie’s oeuvre, the vision feels very full, like it’s trying to reach for everything around her. It’s never just one thing. We’re inside, outside. We’re with people and majestic landscapes. Home encompasses it all and pushes well past four walls.

The night before visiting Opie at her studio, I go and see her give a talk at USC to a room of enraptured students. One of them wants to know how she navigates making such personal work. Opie starts by saying that she used to warn her students that they should think hard about what they put out in the world, because after it’s out there, people will latch on to certain facts about you. She says she’s always felt “very personal with an audience,” but that she’s also kept things to herself. People have become attached to a certain image of who she is that isn’t the “full picture.”

I suppose it’s a common impulse to want to get to know the artists you admire, to feel like you’ve gotten closer to knowing them after meeting them. I look at Opie’s work, I talk with her for an hour, I note the gaps and try to connect the dots. With her in her studio, I feel rewarded, as she gives the impression of not holding back. She is open about her relationships and aspirations. When I ask her about her chair, she seems to be talking about herself. “This was the first chair that I ever felt truly could be a chair that was close to me as a personality,” she says. I ask her why.

“It’s got the delicate bits that could be broken,” she says as she rubs her fingers on one of the two narrow nubs framing the chair. “This could very easily in a move get knocked off, and it would be so sad because then it would have its little delicate expression knocked off.” She then sweeps her hands on the flat, wide arms. “Look at how much space is underneath that, and how it floats and looks like half a potato chip.” She laughs loudly at this comparison, then pauses and softens. “I love the shape and the organic depths of it. This chair is of a body, and it fits a body. There’s a bodily relationship to it that makes it all feel very … I don’t know, complete. Yeah. There’s a completeness to it.”

I’m thinking of Opie’s photographs, how they are many things at once. Like this chair, they are elegant and tough, unpretentious and confident; there are multiple sides to them — it’s what makes them complete and not fully knowable at the same time.

It isn’t until our conversation that Opie realizes she is the only person she’s ever photographed in the Chieftain. As I get ready to turn off my recording device, she slips in, “Who knows. Maybe there’ll be another portrait of this chair before it leaves the studio in August for the new place.” Listening back to the recording, I wonder if she means a portrait of just the chair — an unexpected portrait of her — in this moment in time.