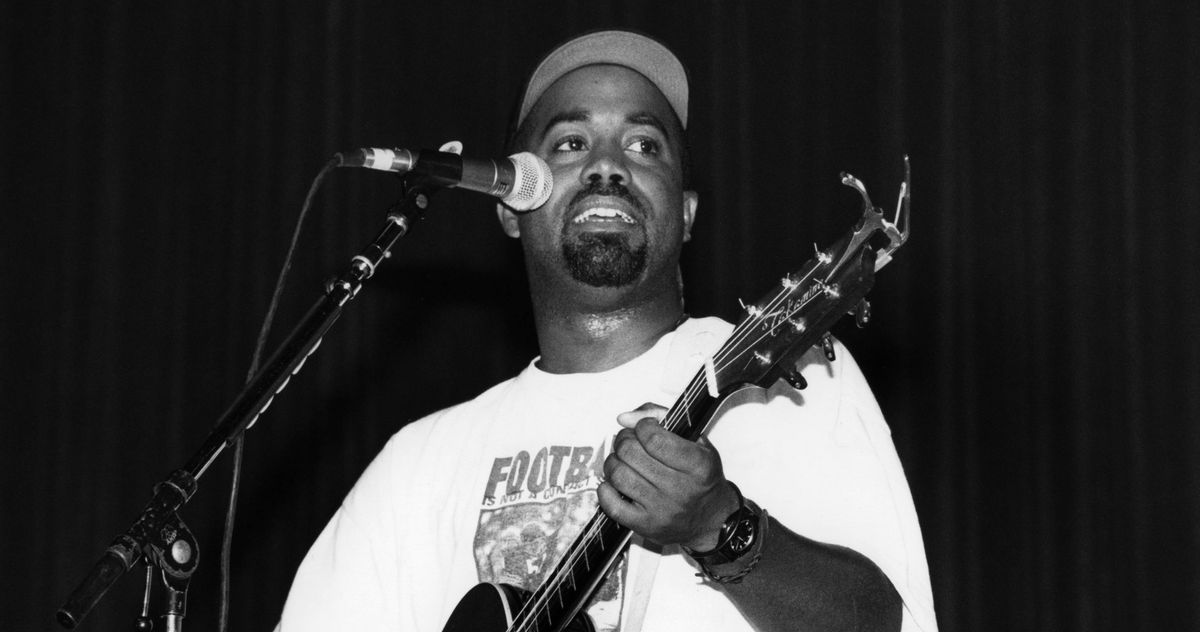

Photo: Matthew Baker/Getty Images

Caroline Polachek is sitting in the sun in front of an “endless hedge” in her Los Angeles backyard, chatting cheerfully about abject loneliness. We’re talking about her new single, “Starburned and Unkissed,” a soaring, bruised track on the carefully curated soundtrack for I Saw the TV Glow, in theaters this weekend. The A24 film is writer-director Jane Schoenbrun’s second, and much like their debut, We’re All Going to the World’s Fair, it’s an eerie exploration of modern alienation, transgender identity, and the way we can lose ourselves in the seductive glimmer of our screens. It’s also something of a love letter to the ’90s, following a pair of teenage suburban outcasts (Justice Smith and Brigette Lundy-Paine) who become unhealthily obsessed with a late-night, SNICK-style TV show called “The Pink Opaque.”

“Starburned and Unkissed” is a departure for Polachek, marking both her first song for a feature film and the first time she’s done, as she puts it, a “straight-up grunge track.” The genre shift is tonally apt for a film that pays painstaking homage to everything from Twin Peaks to Buffy the Vampire Slayer to Are You Afraid of the Dark to the Smashing Pumpkins. This one is for the ’90s kids: Smith’s Owen and Lundy-Paine’s Maddy eagerly pop VHS tapes into their basement TVs late at night to watch their beloved, uncannily lo-fi TV show about teen girls fighting crime on the “psychic plane”; artists like Sloppy Jane and Phoebe Bridgers pop up unannounced to perform freaky, Julee Cruise–style tracks at a local dive; the school’s got Fruitopia vending machines; Owen’s dad is played by Fred Durst. “Starburned and Unkissed” plays over an early scene where Owen wanders, dissociated and alone, down his high school’s track-lit hallways, Polachek’s yearning vocals scoring his inarticulable inner torment.

I saw the movie before I knew you were involved at all, and I instantly heard your voice in the background of that scene and was like, “Wait, this is Caroline!”

It’s actually not a very “me” song, in a lot of ways. It’s a straight-up grunge track, and that’s a genre that I’ve never really dipped a toe into — in terms of the kind of ripping, angsty, full-belt vocal delivery. So the film was a perfect place to do it.

Tell me a little bit about Jane coming to you with the pitch and how it all came together.

Jane approached me in 2022, and at that point We’re All Going to the World’s Fair was out and receiving all the accolades. And I was on tour at the time, and I had just moved to L.A. And as happens when you move to L.A., the brain cells start tingling: Oh, it’d be cool to get involved in films. But I was holding out for the right project. When I watched We’re All Going to the World’s Fair, I was so struck by how inventive it was formally, how genuinely spooky and how totally unique it was. I’d never seen anything like it; it just felt so modern. And of course it was amazing to see Alex G stepping into a scoring role on that film as well. I’m a massive fan of his and anything he touches. At that stage, I Saw the TV Glow was still pretty nascent, so Jane and I had a couple chats where they just sort of described to me the tone and the basic plot points, what was going on, but wanted to keep things really open and also just wanted to attach me to it very early in the process, which was of course a real honor. And as I was setting about to make a song for the film, I suddenly realized that I already had the perfect song sitting in my back pocket.

When did you write it?

Not that much earlier than when Jane originally contacted me. I had just moved to L.A., and moved into this house by myself while my boyfriend was in Europe waiting for his visa to clear, because he’s English. And I was feeling maybe a way that anyone who’s in a long-distance relationship can feel sometimes, which is like, “Is this real? Are you even there? I’m setting up this life for us in this house, but where are you?” The time difference was so severe, and I sort of just felt really shaken by the virtuality of the long-distance situation and everything happening through the phone and it not feeling real.

And so I wrote this really frustrated piece of music sort of about digitally imposed … or maybe, I don’t know, just sort of solitude in the digital age, but through a very surrealist but teenage kind of lyrical bent.

And then I made this song with A. G. Cook in a session around that time when I was still formulating my last album, Desire, I Want to Turn Into You. And he, at the same time, was formulating his rock band called Thy Slaughter and experimenting with pedalboards, which is pretty radical for him because he’s, like, a true digital electronic producer. So for him, having his guitar era was pretty wild. And we synced up in this moment when the style he was exploring really suited this emotion that I was steeped in, and we made this song that didn’t really belong anywhere. I kind of forgot about it, forgot it existed. And then when Jane and I were chatting one day, I realized, “Oh my God, wait a minute. ‘Starburned and Unkissed’ couldn’t fit this film more.”

What about it felt like a fit with the film?

It’s about these two teenagers who are trying to find themselves and their gender expression and their life paths in this place that doesn’t fit. And at the same time, they’re so consumed with the screen, screens pulling them in, and they have this push-pull with it. And I was like, Wait a minute. Yes, yes. This is it. I sent Jane a rougher version of the song, and they freaked out. They were like, “I’m building a cue around this song. It’s going to get this hallway sequence.”

Who was in your mind, who were you channeling, when you were going for this ’90s grunge moment with it? Was it, like, Alanis?

So I was too young to participate in actual grunge — I was 10 years old when Nirvana, when Alanis were peaking, and I think I experienced it in a very kid way. I experienced it through MTV. I experienced it through bands like Silverchair, which were late-generation, glossy major-label teen grunge. And then I watched it sort of have multiple levels of revival in things like Sky Ferreira, in kind of nü-metal incarnations like Kittie. I was obsessed with Kittie. And then I sort of came face to face with it in a really unexpected way when my boyfriend, Matt Copson, was commissioned to write the libretto for an opera about Gus Van Sant’s film Last Days, which I realize is so many steps removed from Kurt Cobain. But it was about Kurt Cobain’s suicide, and that film was adapted into opera. And the idea behind that opera was to completely not include any grunge music at all, but to sort of get at the feeling of it, the angst of it, and put it in a classical music vocabulary. So I was living in the periphery of all these conversations about grunge music without the grunge actually there. So Kurt Cobain became a kind of symbolic fixture in the house for the last couple of years.

What kind of conversations did you and Jane have about the movie’s tone? What kind of things clicked for you in terms of the movie’s aesthetics?

We spoke really compellingly about this sort of crossover between the feeling of horror and the feeling of crush, where there’s this sort of liminal adrenaline feeling that connects the feeling of fear and crushing. Later, seeing the film, I could really understand where that was coming from. But that was a sort of footnote for me while I was finishing the music.

In the press notes, Jane talks about how they wanted the soundtrack to feel like an “essential contemporary document of the vanguard of queer music right now.” What does that mean to you? Does it feel like a “queer song” to you?

It does, the more and more I live with it, actually, because I think it’s about that kind of frustration. And that battle between the virtual embodiment I think is a big part of so many queer journeys and especially teenage ones. And of course, those are all things that I felt as well. But I think especially in the narrative of queer experience, it feels super synced up.

How did you, or do you still, relate to this concept of being someone who felt out of place in reality, but embodied or deeply understood by a piece of art? Is there art — or was there art — that did that for you?

Oh my God, I will never forget hearing Kid A for the first time. I was at my grandmother’s 80th birthday, which was sort of a family reunion. We all went down to Florida. And there was a golf course at the edge of the place we’d rented to have the party in, and I snuck away from the party and put my headphones on and had the Kid A CD. I’m wandering around this golf course, which is closed, in this kind of impossibly dense sunlight. And I think maybe I never felt more alone and more seen at the same time, in that album. The feeling of alienation, the feeling of coming up against the systems of reality, whether it’s the work system, the education system, the digital world — it was all just done with so much sophistication and dreaminess and sexiness. And I was just like, ‘Oh my God, I didn’t know that art could do this.’ I was just so rocked by that album, and still am.

I had a very similar experience with that album at that age. It blew my mind.

Where were you?

I remember listening to it in my room on my little CD player with five little CD slots — that and Fiona Apple’s Tidal just on repeat. Just blew my mind. What’s the most recent thing that has done that for you?

Ooh, that’s a cool question. Okay, let me simmer in alienation. Am I allowed to open my Spotify? I take this question very seriously.

I would love that. Yeah.

[She disappears for a minute.] Okay. Pretty much the entire Oneohtrix Point Never catalogue does that same thing for me, but also this French artist called Torus. It gives me that same kind of … What do they call it when you’re out of your body and you’re dreaming?

Astral projection?

Yes. It gives me that same kind of hyper modern, lonely, astral-projected feeling. This artist Malibu, her work does that as well, but all in very different ways. I think I’ve probably clocked more hours of listening to Malibu than anyone else in the world because that’s all I listen to when I’m flying, when I’m on tour.

Something I’ve been thinking about a lot, after watching the film twice now, is this idea of art as a life raft, but also something that can drown you. I’m curious how you’ve navigated that as an artist, from your end, whether it’s your relationship to your art or to your fans. Do you feel that you have to sort of draw a line there?

Wow, that’s so interesting to position the movie as about fandom, actually, or the siren song or even the toxicity of fandom. I think I’ve honestly been exceptionally lucky to have really cool fans, but I was chatting with a friend of mine over the weekend who has a stalker who threatens to kill himself all the time. And the kind of responsibilities that artists get put in, in those kinds of positions — I can’t even imagine how distressing that must be. But there’s an interesting waltz with boundaries, because ultimately what you’re trying to do as an artist is create a compelling world that has infinite depth, that people can keep going into and keep going into. And as an artist, I’m making it because that’s what I love in art, not because I’m really trying to manipulate anything. But I think there is a question of responsibilities too, once people do go all the way in. What is your relationship with them? What do you owe them? What do they owe you? And I don’t have the answers to any of these things, but we’re definitely living in a time where those boundaries are getting wild as hell.

Your music is very aesthetically minded and everything is tied together in this specific world you’ve created, sort of like the world of the Pink Opaque. I wonder if people feel like they know you or own a piece of you because of that.

I think there’s definitely an impulse to speak to artists online, and I’m definitely subject to this as well, as if they owe you things and as if you can tell them what to do or sway their output in different directions. I find it very easy to ignore that. Incredibly easy. But I think it’s also because my music, even with a song like “Starburned and Unkissed” that does come out of a personal situation in my life, I’m not Taylor Swift. I’m not describing in very narrative musical theater terms the actual events of my personal life. I’m not an open book, and I never really have been. I’m much more interested in the slippery lines between dreaming and symbolism and the texture of reality — just letting things go into this space where the reality is found in the fantasy. I think the film is also about that, especially in the way that transitioning is depicted in the film. But I think that’s the kind of language my music exists in, which thankfully, I think, helps people intuitively understand a sort of boundary because they have to meet me in that dream space. They’re not meeting me in the reality space. So there’s no leverage in the reality space either.

I was just reading an interview with Jane where they said, “Promoting a movie as a trans person right now involves a participation within the capitalist machinery that I’m too sensitive not to be sickened by, so I need to go and remember who I am.” Do you feel that you have to kind of step back and heal yourself from these types of things?

When I was younger, I felt like these kinds of things were really violent — the branded stuff, the promo, the need to present in a capitalist landscape this work that felt so personal. And the more I’ve grown up, the more I don’t really see the difference anymore and I can actually approach it with a lot of goodwill. I’m like, “Oh, the people in these spaces are here because they want to make good shit, and I’m here because I want to make good shit, so let’s just get on with it.” And maybe that just comes with getting older and feeling less defensive and less scared of people. The older I get, the more I see it all as one playground.

I want to talk a little bit about your made-up words. “Wikipediated,” “mythocological,” “hopedrunk.” Do these come fully formed to you? Do you labor over them?

I’m really inspired by how German does it, just these endless compound words. But beyond loving how it looks and how kind of, I don’t know, psychedelic and yummy and Alice In Wonderland-y it is to have these compound words, it’s just straight-up useful often in songs, not just for lyrical phrasing, but trying to say something succinctly. I think if I was to try and say “starburned and unkissed” in another way, it would take me three times the amount of syllables. So it’s sometimes just economic to do it.

In the case of a song like “Blood and Butter,” which has the words “mythocological” and “Wikipediated” in it, that was actually purely practical because the rhythms of that verse had to be so specific. It was almost like a drumbeat [sings] da da da da da da, da da, da da, da da, da da da, and that was a big part of the hook of that song, sticking with these rhythmic patterns. And unfortunately, the lyrics that I wanted to say were either too short or too long for those phrases. So I had to add. I wanted to say mythological, but I was two syllables short, so I was like, “Fuck it, I’m adding a couple of syllables in here.” And then “Wikipediated,” I wanted to describe something much more elaborate, but I couldn’t squeeze it into the line. I was trying to describe someone who just gets high off knowledge, and so I had to just be really creative about squeezing it down.

What about “starburned and unkissed”?

I remember distinctly walking around L.A. as we just moved here and feeling like, Oh my God, this is so hostile. This environment is so Martian. I don’t even feel like it’s the sun. I feel like the atmosphere isn’t even there. I feel like I’m in outer space, like I’m being scalded by this star that’s just giving me some kind of ultraviolet cancer. I shouldn’t be here, as an animal. And in my Notes app, while scribbling about it, the word “starburned” came up and I was like, Oh, I like how that almost plays into Hollywood and showbiz and all this stuff as well.” So I just had that word kicking around, and then it made a nice layer cake with my temporary celibacy. [Laughs.]

I remember when we spoke a few years ago, you said you’ll sing along to a track and the words will come out while you’re doing the melody pass. I’m curious about the evolution of the lyrics in this one, which are really visually evocative: “Deep fried, this isn’t how to be, naked of charms in your long sleeve, a bitter little seed, a digital sand.”

I am a melodic writer. I always start with just a scratch non-lyrical vocal. In the case of this one, I just sounded so tired and just so frail and blah in the take. And I said, “Okay, I love that, and I want to actually keep that spirit through the lyrics.” So to go chronologically: “Deep fried” comes from the style of memes where you take an image and you sort of compress it through screenshotting it endlessly, and it starts to take on that really crusty, crispy, almost neon color-saturated look, like a deep fried JPEG or deep fried meme. I was just thinking stuff like, that’s not only how I feel, but also how I feel like my image looks, like on FaceTimes, and it’s really unflattering and crusty. “This isn’t how to be” in a relationship or as a person — “naked of charms,” without any of my affectations or my maintenance, just doing these calls right in the morning when I’ve just woken up, no chance to groom myself or no perfume. Not much to respond to, just turning up without any charms. And a seed being planted in sand — it can’t grow first of all, but especially if the sand isn’t physical, it definitely can’t grow, which is kind of how I felt. The lyrics are fun pictures, but they really actually were very personal, all of them.

You just finished your tour, right? Are you home for a while? Are you chilling? Are you working on new stuff?

Yeah. I’ve taken a couple weeks just to rest. This last month I’ve just been doing some kind of systems renovation, rebuilding my digital life, my plug-in library, my cybersecurity stuff, my archives. Just getting ready to plunge myself into the next album. But it feels like a massive luxury just to be able to take a beat before getting into writing. I had to write a lot of Desire while I was on the road touring Pang. So it feels like a luxury to just be able to stop and think. And I’ve been doing a lot of writing, which is interesting. Because as I was saying before, I tend to write melodically first, but I’ve stored up so much writing this last month that I think there might be a lot of material on the next album that actually is text-driven, which is new for me. So we’ll see.

So you’re giving yourself a long runway for this one?

Yeah, I’m definitely going to let the writing and the music guide the schedule. So music’s going to take precedence over anything else being booked in. So yeah, it’ll be finished when it’s finished, which is, again, a massive luxury.