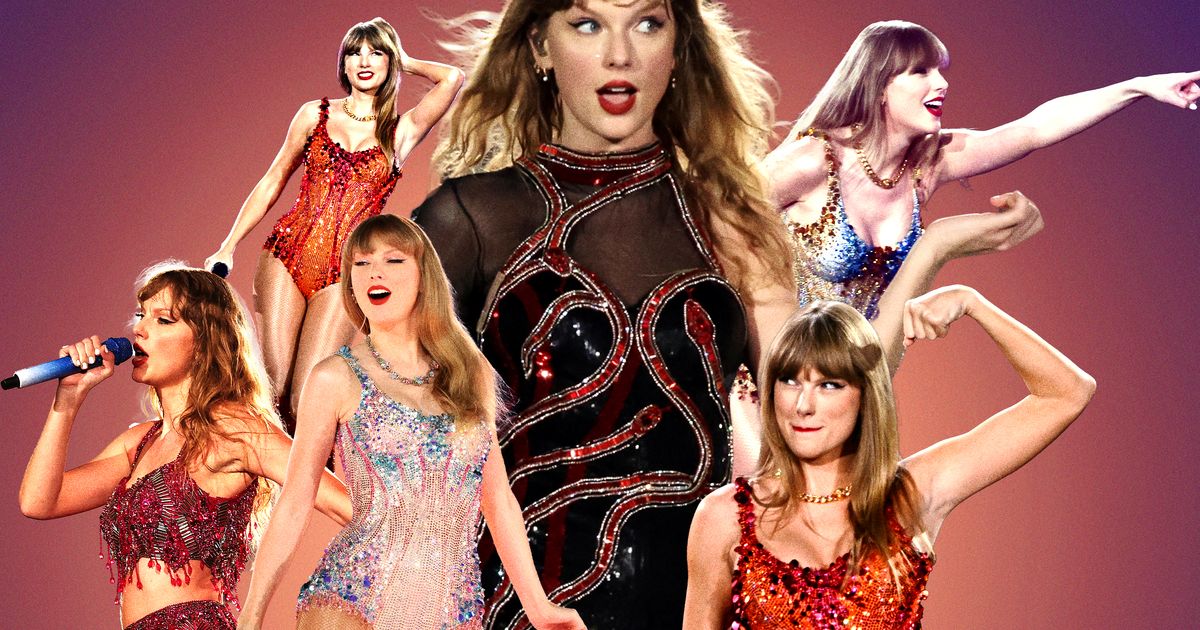

Photo-Illustration: James White

Taylor Swift was born in December 1989, near the peak of the Millennial Baby Boom, and has been famous since she was 16. Meaning that, for millions of listeners, she is not just another pop star; she is someone they have grown up with, and who has grown up with them. To chart her journey — from the country romance of her teens, to the imperial pop of her twenties, to the ambivalent ruminations of her thirties — is to follow a generation coming of age. Though the sound of her music has evolved since her debut, the voice at the heart of it has stayed consistent. The Swift we hear on her albums is a thin-skinned, bighearted obsessive, prone to introspection, with a penchant for romantic moments huge and small.

That’s the artist. There’s also the empire. “Like so many millennials born into the upper middle class, Swift has benefited from the demise of the concept of selling out,” Time noted in 2014. As a celebrity, Swift’s most remarkable gift is her ability to keep art and commerce, public life and private life, operating in lockstep. There have been wobbles, most notably in 2016-17, but on the whole she has retained a command of her star image rivaled only by Beyonce and Bowie. There is no daylight. The person is the music is the brand.

Which is why, whether you’re a casual listener who bops along to the radio hits, or one of those die-hards who takes her every utterance as a modern Rosetta Stone, it’s easy to feel like you know Swift on a personal level. Listen to her songs and you’ll ache at the resemblance to the most dramatic moments in your own private history. Listen to too many and you might ache again at the nagging feeling that those stories of yours have all been a bit uneventful and drab by comparison. Returning to them every few years, as I have since writing this list, is a strangely melancholy experience. The passage of time hits you like a brick.

Swift also benefited from the widespread critical embrace of poptimism, to the point where she could be named Time’s Person of the Year in 2023. If this list does anything, I hope it convinces you that, underneath all the think pieces, exes, and feuds, she is one of our era’s great singer-songwriters. She may not have the raw vocal power of some of her competitors, but what she lacks in Mariah-level range she makes up for in versatility and personality. (A carpetbagger from the Pennsylvania suburbs, she became an expert code-switcher early in her career and never looked back.) And when it comes to writing instantly memorable pop songs, her only peers are a few anonymous Swedish guys, none of whom perform their own stuff. I count at least fifteen stone-cold classics in her discography. Others might see more. No matter how high your defenses, I guarantee you’ll find at least one that breaks them down.

Some ground rules: We’re ranking every Taylor Swift song that’s ever been released with her name on it — which means we must sadly leave out the unreleased 9/11 song “Didn’t They” as well as Nils Sjöberg’s “This Is What You Came For” — excluding tracks where Swift is merely “featured” (no one’s reading this list for B.o.B.’s “Both of Us”) but including a few duets where she gets an “and” credit. The original version of this list included covers; the updated version of 2023 removes these in the interest of concision, as well as recognition that songwriting is an essential element in Swift’s songbook. For similar reasons, the “Taylor’s Version” re-recordings are not afforded their own blurbs. Finally, because Swift’s career began so young, we’re left in the awkward position of judging work done by a literal high schooler, which can feel at times like punching down. I’ll try to make slight allowances for age, reserving the harshest criticism for the songs written when Swift was an adult millionaire.

*This list was originally published in November 2017. It has been updated to include Swift’s subsequent releases and vault tracks. Additionally, many rankings have changed to reflect the author’s evolving taste. Like another famous Pennsylvanian, this is a living document.

Most Swift songs grow with each listen. “Me!” is the exception: The more you hear it, the worse it sucks. After the Sturm und Drang of the Reputation era, “Me!” was a return to bubblegum pop, a mission statement that says “I’m through making mission statements.” While self-awareness may be Swift’s superpower, it fails her here. The attempt to reclaim a sense of youthful innocence works only by stripping out anything else that’s interesting or pleasurable about the music. Indeed, there’s something patronizing about kicking off an album full of gems like “Cornelia Street” and “Cruel Summer” with a song that makes Kidz Bop sound like In Our Time. She was seven years past “All Too Well” at this point, long enough to put away the baby food.

One of two originals on Swift’s early-career Christmas album, “Something More” is a plea to put the Christ back in Christmas. Or as she puts it: “What if happiness came in a cardboard box? / Then I think there is something we all forgot.” In the future, Swift would get better at holding onto some empathy when she was casting a critical eye at the silly things people care about; here, the vibe is judgmental in a way that will be familiar to anyone who’s ever reread their teenage diary.

A nasty little song that has not aged well. Whether a straightforward imitation of Avril Lavigne’s style or an early attempt at “Blank Space”–style self-satirization, the barbs never go beyond bratty. (As in “Look What You Made Me Do,” the revenge turns out to be the song itself, which feels hollow.) Best known now for the line about “the things she does on the mattress,” which I suspect has been cited in blog posts more times than the song was ever listened to, and has now been excised from the re-recording.

“There’s a mistake that I see artists make when they’re on their fourth or fifth record, and they think innovation is more important than solid songwriting,” Swift told New York back in 2013. “The most terrible letdown as a listener for me is when I’m listening to a song and I see what they were trying to do.” To Swift’s credit, it took her six records to get to this point. On a conceptual level, the mission here is clear: After the Kim-Kanye feud made her the thinking person’s least-favorite pop star, this comeback single would be her grand heel turn. But the villain costume sits uneasily on Swift’s shoulders, and even worse, the songwriting just isn’t there. The verses are vacuous, the insults have no teeth, and just when the whole thing seems to be leading up to a gigantic redemptive chorus, suddenly pop! The air goes out of it and we’re left with a taunting Right Said Fred reference — the musical equivalent of pulling a Looney Tunes gag on the listener. (I do dig the gleeful “Cuz she’s dead!” though.)

While it’s understandable to wish Swift would have done more during the 2016 election, the effort to affix some blame to her for Hillary Clinton’s defeat rests on flimsy foundations. The Clinton campaign was hardly lacking for celebrity endorsements, and as Swift herself has pointed out, at that moment she was as hated as she’d ever been. Any attempt to link her brand with Clinton’s likely would have rebounded to the detriment of them both. Nevertheless, whether in response to this backlash or simply to the obvious, Swift got more comfortable wading into the partisan arena during the Trump era, an evolution that takes center stage in her 2020 documentary, Miss Americana. This was an admirable thing to do, even if it hasn’t always resulted in good music. As the doc’s closing number makes clear, politics remains an awkward fit creatively. Swift isn’t a natural polemicist, straining her way through clunky couplets about the “big bad man” and his “big bad clan.” Docked at least a dozen spots for the verse about school shootings, the most cringeworthy of Swift’s recent output.

A bonus track from the debut that plays like a proto–”You Belong With Me.” The “show you” / “know you” rhymes mark this as an early effort.

Unable to express themselves openly in popular art, the queer community historically has needed to operate through secret code. Since this is also Swift’s preferred method of communicating with superfans, it should come as no surprise that many of them thus convinced themselves the singer was implanting in her lyrics and music videos veiled references to her own Sapphic desires. Like ancient Christians expecting the imminent arrival of the Kingdom of God, the Gaylors may be destined never to experience the glorious day they’ve been waiting for, though they have the cold comfort of this Lover single, where Swift came out as an LGBTQ ally and buried the hatchet with Katy Perry, all at the same time. Besides being politically incoherent — was Tweeting at 7 a.m. really the thing that was bad about Donald Trump? — its slangy jabs felt dated even at the moment of release, as did the slight West Indian accents in the chorus. Coming hot on the heels of “Me!” this track did not get the Lover era off to the strongest of starts. As with Reputation, the real gems would emerge on the album proper.

When approached by the filmmakers about contributing a song to the Hannah Montana movie, Swift sent in this track, seemingly a holdover from the Fearless sessions. In an admirable bit of dedication, she also showed up to play it in the film’s climax. It’s kind of a snooze.

A bit of paint-by-numbers inspiration that apparently did its job of spurring the 2008 U.S. Olympic team to greatness. They won 36 gold medals!

Swift’s version of “Not a Girl, Not Yet a Woman,” this one feels like it missed its chance to be the theme tune for an ABC Family show.

This bonus track is a relic of an unfamiliar time when Swift could conceivably be the less-famous person in a relationship.

Swift’s first foray into musical-theater writing is less embarrassing than the movie but still far too self-pitying to sit through more than once. Ever the dutiful student, Swift follows all the parameters of the assignment, yet moves like rhyming wanted with wanted come off as rookie mistakes.

There’s a thin line between timeless and basic, and this “from the vault” track stays on the wrong side.

After joining Big Machine, McGraw gave Swift an “and” credit here as a professional courtesy. Though her backing vocals are very pleasant, this is 100 percent a Tim McGraw song.

A mid-tempo breakup song from the vault that never achieves liftoff, though Jack Antonoff’s production at least gives it an alluring shape.

A pleading breakup song with one killer turn of phrase and not much else.

Swift’s vault tracks often feel like drafts for ideas that would be more fully sketched out in her official tracks — and never more so than on this one, whose opening notes are reminiscent of the beginning of “I Almost Do.”

A dead-serious breakup song that proved the teenage Swift could produce barbs sharper than most adults: “You come away with a great little story / Of a mess of a dreamer with the nerve to adore you.” Jesus.

If you thought you felt weird judging songs by a high-schooler, here’s one by an actual sixth-grader. “The Outside” was the second song Swift ever wrote, and though the lyrics edge into self-pity at times, this is still probably the best song written by a 12-year-old since Mozart’s “Symphony No. 7 in D Major.”

Finally, Travis Kelce gets his own “London Boy.”

An ambient vibe that floats around without ever achieving much.

Another vault track that bears some vestigial similarities with a more famous Swift song, in this case, “You Belong With Me.” Keith Urban shows up to add a bit of country verisimilitude but not much interest.

Red is Swift’s strongest album, but it suffers a bit from pacing issues: The back half is full of interminable ballads that you’ve got to slog through to get to the end. Worst of all is this duet with po-faced Ulsterman Gary Lightbody, which feels about ten minutes long.

A bonus track that’s not gonna make anyone forget Five for Fighting any time soon. But I heard it playing in an airport a few years back, and it was better than I remembered.

Another glacially paced song from the back half of Red that somehow pulls off rhyming “magic” with “tragic.”

The title track of Swift’s early-career EP finds the young songwriter getting a lot of mileage out of one single vowel sound: Besides the eyes of the title, we’ve got I, why, fly, cry, lullaby, even sometimes. A spirited vocal performance in the outro saves the song from feeling like homework.

A plight-of-fame ballad from the back half of Red, with details that never rise above cliché and a melody that borrows from the one Swift cooked up for “Untouchable.”

The most interesting things here are all in the background: the backing oohs, the noodly bass. The guitar sounds like late-period Graham Coxon.

Swift’s embrace of a harder sound on Reputation led her to try her hand at rapping, most notably on this single, which sees her employ an awkward blaccent. Future and Ed Sheeran show up to form a Megazord of soulless late-’10s pop.

One of two songs Swift contributed to the first Hunger Games soundtrack. With guitars seemingly ripped straight out of 1998 alt-rock radio, this one’s most interesting now as a preview of Swift’s Red sound.

When she was just a teenager with a development deal, Swift hooked up with veteran Nashville songwriter Liz Rose. The two would collaborate on much of Swift’s first two albums. “We wrote and figured out that it really worked. She figured out she could write Taylor Swift songs, and I wouldn’t get in the way,” Rose said later. “She’d say a line and I’d say, ‘What if we say it like this?’ It’s kind of like editing.” This early ballad about a friend with bulimia sees Swift and Rose experimenting with metaphor. Most of them work.

Sara Bareilles–core.

The disparate reactions to Kanye West stage-crashing Swift at the 2009 VMAs speaks to the Rorschachian nature of Swift’s star image. Was Swift a teenage girl whose moment was ruined by an older man who couldn’t control himself? Or was she a white woman playing the victim to demonize an outspoken black man? Both are correct, which is why everyone’s spent so much time arguing about it. Unfortunately, Swift did herself no favors when she premiered “Innocent” at the next year’s VMAs, opening with footage of the incident, which couldn’t help but feel like she was milking it. (Fairly or not, the comparison to West’s own artistic response hardly earns any points in the song’s favor.) Stripped of all this context, “Innocent” is fine: Swift turns in a tender vocal performance, though the lyrics could stand to be less patronizing.

This Red bonus track offers a foreshadowing of Swift’s interest in sparkly ’80s-style production. A singsongy melody accompanies a largely forgettable lyric, except for one hilariously blunt line: “It would be a fine proposition … if I was a stupid girl.”

This early track was inspired by Swift’s elderly neighbors. Like “Starlight,” it’s a young person’s vision of lifelong love, skipping straight from proposal to old age.

In 2023, Olivia Rodrigo released a song called “get him back!” Seven months later, Swift put out one with an almost identical conceit and striking lyrical similarities. (Rodrigo: “I want to key his car; I want to make him lunch.” Swift: “Whether I’m gonna be your wife or gonna smash up your bike, I haven’t decided yet.”) You can dive into pop-star Kremlinology regarding the pair’s relationship if you’d like, but this is likely a simple case of parallel thinking rather than plagiarism, especially as the two songs sound nothing alike. Still, in pop it’s better not to race than come in second, and it’s not like Swift’s version is so mind-blowing that it absolutely needed to be included on an album that stretches past the two-hour mark. Docked 20 spots for hubris.

A vulnerable track about long-distance love, with simple sentiments overwhelmed by extravagant production.

Never forget that one of the most critically acclaimed albums of the 2010s contains a piece of Ethel Kennedy fanfiction. The real story of Bobby and Ethel has more rough spots than you’ll find in this resolutely rose-colored track, but that’s what happens when you spend a summer hanging in Hyannis Port.

Reputation sags a bit in the middle, never more than on this forgettable ’80s-inspired track.

An attempt at channeling the naturalistic imagery of the Lake Poets winds up overwrought and overwritten. Though I do smile at the Wordsworth pun. (And yeah, sorry, I’m not gonna do the lowercase thing for the Folklore tracks.)

Swift broke out her southern accent one last time for this attempt at homespun folk, which is marred by production that’s so clean it’s practically antiseptic. In an alternate universe where a less-ambitious Swift took a 9-to-5 job writing ad jingles, this one soundtracked a TV spot for the new AT&T family plan. In ours, it’s her “Ob La Di, Ob La Da.”

Once freed from the expectation that everything was autobiography, Swift began to dive into the heads of straying partners. This one has an intriguing line about April 29 that invites a lot of speculation from gossip-minded listeners, but it pales next to similar efforts on Folklore and Evermore.

In Fifty Shades Darker, this wan duet soundtracks a scene where Christian Grey and Anastasia Steele go for a sunny boat ride while wearing fabulous sweaters. On brand!

How far has Swift come from her Nashville days? So far that this country-tinged murder tale with the Haim sisters can’t help feeling more like a musical costume party than a genuine attempt at embodying darkness.

An ode to a long-lost lover that follows the Swift template a tad too slavishly.

Like “You Are in Love,” this one originated as a Jack Antonoff instrumental track, and the finished version retains his fingerprints. Perhaps too much — you get the sense it might work better as a Bleachers song.

Swift code-switches like a champ on this charmingly shallow country song, which comes from the Walmart-exclusive EP she released between her first two albums. Her vocals get pretty rough in the chorus, but at least we’re left with the delightful line, “Wake up and smell the breakup.”

Not actually about Paris, which spared Swift getting the Emily Cooper treatment from angry French people. I don’t think she needed to explain which kind of “shade” she meant. We all got it.

On paper, this is interesting, picking up the thread of Swift’s fascination with vivacious women of the 20th century from “The Last Great American Dynasty.” But, in a casualty of TTPD’s sprawling run time, I’m tapped out by the time it comes around. The only thing that pricks my ears up is the nod to “Mr. Brightside.”

Apparently inspired by a Netflix rom-com, and that tells you everything you need to know.

Is it disrespectful to the generation of young men who perished at the Somme to use their deaths as a metaphor for an argument with Joe Alwyn? After 100 years, I say it’s fine.

Another “post-breakup catharsis” song, seemingly left off Evermore in favor of “Happiness.” The lyrics are about a romantic separation, but subtextually there are references to the Big Machine split, particularly when a banjo shows up.

An unflinching kiss-off song that got a gothic remix for Swift’s appearance as an ill-fated teen on CSI. It shouldn’t work but it does, somewhat.

Considering her go-to themes, how did it take Swift nearly 20 years to get around to writing a Peter Pan song?

Not, as the title might imply, a slinky cheating ballad. Instead, it’s a straightforward love song. The stripped-down production in the verses makes a fun contrast with the bubbly chorus, but otherwise there’s not much here.

In retrospect, there could not have been a song more perfectly designed to tick off the authenticity police — didn’t Swift know that real New Yorkers stayed up till 3 a.m. doing drugs with Fabrizio Moretti in the bathroom of Mars Bar? I hope you’re sitting down when I tell you this, but it’s possible the initial response to a Taylor Swift song might have been a little reactionary. When it’s not taken as a mission statement, “Welcome to New York” is totally tolerable, a glimmering confetti throwaway with lovely synths.

Nathan Chapman was a Nashville session guitarist before he started working with Swift. He produced her early demos, and she fought for him to sit behind the controls on her debut; the two would work together on every Swift album until 1989, when his role was largely taken over by Max Martin and Shellback. Here, he brings a sprightly arrangement to Swift’s ode to an achingly good-looking man.

The best part of this one is its big honkin’ hook that would have fit perfectly on country radio or maybe even Grey’s Anatomy.

I don’t know if I buy the theory that Midnights is a collection of old songs that were gathering dust in Swift’s desk drawer, but I absolutely do believe this one is a Reputation holdover.

One good line here: “flush with the currency of cool.”

The fake-out here makes me smile: She goes winter-jazzy in the intro, then hustles backstage to throw on some Mariah Carey drag. Swift says she wrote it in a weekend, and it definitely feels like a lark, something she tossed off not because she dreamed of knocking Burl Ives off the charts, but simply because she thought it’d be fun.

Unfortunately not a Nick Lowe cover, this one comes and goes without making much of an impact, but if you don’t love that whispered “1-2-3,” I don’t know what to tell you.

A bonus track saved from mediocrity by a gutsy outro that hints that Swift, like any good millennial, was a big fan of “Semi-Charmed Life.”

I worked at an American Eagle in the summer of 2006, and I swear they played this song on the speakers.

One of the few bad things you can say about Swift’s quarantine reinvention is that it exacerbated her penchant for glum duets with dad rockers. After getting the National’s Aaron Dessner to produce much of Folklore and Evermore, Swift teamed up with the whole band for this track, which feels so heavy and middle-aged you’d swear it was interviewed for Meet Me in the Bathroom. She blends in all too well: Which one is the featured artist, again?

Technically a Luna Halo cover (don’t worry about it), though Swift discards everything but the bones of the original. Her subsequent renovation job is worthy of HGTV: It’s nearly impossible to believe this was ever not a Taylor Swift song.

In which Swift tries her hand at Evanescence-style goth-rock. She almost pulls it off, but at this point in Swift’s career her voice wasn’t quite strong enough to give the unrestrained performance the song calls for.

A Colbie Caillat collaboration that’s remarkable mostly for being a rare Swift song about a friend breakup. It’s like if “Bad Blood” contained actual human emotions.

Writing about the Beatles’ White Album, Ian MacDonald noted that its original title, A Doll’s House, would have been more apropos for the “musical attic of odds and ends.” “There is a secret unease in this music,” he writes, “associations of guarded privacy and locked rooms.” I get a similar vibe from TTPD, another divisive double album that feels like a box of curios someone stumbled upon in a crawl space. This two-minute track is the album’s equivalent of something like “Cry Baby Cry” — a creepy little sketch that in a more judicious era probably wouldn’t have left the vault.

A clever vault track with a lyrical Easter egg: Swift’s first use of the phrase “casually cruel,” four years before “All Too Well.”

A good-bye waltz with an understated arrangement that suits the starkness of the lyrics.

Miss Havisham cosplay, as Swift sings from the perspective of a woman who’s been frozen at the time and place she got dumped. In the documentary Miss Americana, Swift spoke about how celebrities are often mentally stuck at the age they were when they got famous, something she struggled with as she approached 30, but the metaphor is overwhelmed by the song’s Gothic elements.

A woozy R&B track livened up by an undaunted vocal performance and a saxophonist really making the most of their time in the spotlight.

Began life as a poem before evolving into an atmospheric 1989 deep cut. Like an imperfectly poached egg, it’s shapeless but still quite appetizing.

Swift’s parents moved the family to Tennessee so she could follow her musical dreams, and she paid them back with this tender tribute. Mom gets the verses while Dad is relegated to the middle eight — even in song, the Mother’s Day–Father’s Day disparity holds up.

The mirror image of “White Horse,” which makes it feel oddly superfluous.

When reaching for insight outside her own experience, Swift occasionally grasps for platitudes. In this ode to soldiers and frontline health-care workers we get both “just a flesh wound” and “someone’s daughter.” Credit to the singer for expanding outside her usual vocal range, though, deploying an Imogen Heap–style yawp on this one.

What do we want from a vault track? “Foolish One” has the advantage of sounding a lot like the other songs Swift was writing in the Speak Now era, rising climax and all. But apart from a stray use of delicate and a bridge that echoes the coda of “Enchanted,” little distinguishes this pleasant tale of romantic woe from its peers.

TTPD has sequencing issues, never more than when it ends with nine muted acoustic tracks in a row, almost all of them downbeat in ways I find hard to distinguish. (For this reason, I think the songs play better on their own than in the context of the album.) They’re not all bad, but this is the least bad of them. That infamous 1830s line may have been taken slightly out of context — you know the Swifties are on their heels when they break out the image-editing software — but it marks the point when casual listeners who joined the Swift bandwagon on folklore jumped off again.

I remember really hating this single and scoffing at Swift’s bars about Elizabeth Taylor and the flow she borrowed from Jay-Z. (Try to rap “Younger than my exes” without spilling into “Rest in peace, Bob Marley.”) But you can’t deny the chorus, a big Swift hook that sounds just like her best work — in this case because it bites heavily from “Wildest Dreams.”

When it comes to ending an album on a note of catharsis and elemental imagery, I prefer “Clean.” And when it comes to employing this specific melody and cadence in a refrain, I prefer Beyoncé’s “Halo.” But I do love a good spoken-word mission statement!

The title baits fans who examine every line for real-life reference points; the song never gets out of second gear. Although I do love the little arpeggio on the guitar.

A deranged bonus track that sees Swift doing the absolute most. This song has everything: Alice in Wonderland metaphors, Rihanna chants, a zigzag bridge that recalls “I Knew You Were Trouble,” screams. As she puts it, “It’s all fun and games ’til somebody loses their MIND!”

Being happily coupled up did not diminish Swift’s ability to write heartbreaking songs about dying relationships; in this case, a study of a woman coming to grips with the fact that her partner has settled for her. Everything is off-balance, including the time signature, which is in 5/4. The cold, oppressive weight doesn’t lift until the bridge, when Swift leaps into her upper register to dream about getting the courage to break it off: “Believe me, I could do it.” But then the daydream ends, and we snap back to where we started. It’s clear she doesn’t quite believe it herself.

How much of a roll was Swift on during the Fearless era? This song didn’t make the album, and sat in the vault for a year until Swift signed on for a small role in a Garry Marshall rom-com and offered it up for the soundtrack. Despite the extravagant title, the date described here is charmingly low-key: The dude wears a T-shirt, and his grand gestures are showing up on time and being nice.

A once-elusive track that was available on the Target deluxe CD of Midnights. (It would later be added to the Til Dawn edition.) The title is a real “How do you do, fellow kids?” moment, but otherwise this is a pleasant break-up song enlivened by some weirdly specific lines about vomiting in the street. Compare the “ay-ee-ay” sound in the first line to that in “The Very First Night.”

With a different vocal delivery, the frenzied paranoia here would sound almost Nixonian. Also, not all of us were quiet when the truth came out!

The song that gave the entire United Kingdom a chance to clown on Taylor Swift, which is the best gift the nation has received from an American since FDR’s Lend-Lease Act. British Twitter was particularly hung up on the fact that it’s impossible to visit every neighborhood she name-drops in one day … but nowhere in the song does Swift mention it’s supposed to be one day. It’s that kind of sloppiness that cost them the empire.

A vault track that sees Swift wishing she could “go back in time” to relive those heart-pounding early dates all over again. It’s not much on its own, but it does make you think about how these rerecordings let her go back in time, at least in a sense: She was an established grownup momentarily reliving the rushing passions of her youth. For a born memoirist like Swift, that must have been a dream come true.

Is it disingenuous to write a thinly veiled diss track that ends with a patronizing thank-you to your nemesis for helping you grow, then capitalize their name in the title so even idiots will get who you’re talking about? Of course. Still, there’s a fetching melody on this one that recalls Swift’s early work. Bonus points for mid-aughts PA-suburb verisimilitude: I lived across the street from an Aimee.

Swift’s first collaboration with Jack Antonoff is appropriately ’80s-inspired, and so sugary that a well-placed key change in the chorus is the only thing that staves off a toothache.

A rollicking pop-rock tune that recalls early Kelly Clarkson. As if to reassure nervous country fans, the fiddle goes absolutely nuts.

The metaphor works, but I don’t think the abrupt slowdown in the final minute does.

Another story of a lousy boyfriend, but it’s paired with one of Swift and Rose’s most winning melodies.

Beyoncé’s “If I Were a Boy” transported to the world of media meta-narratives. The chorus sums up so much you barely even need the rest. But it also feels more like a viral op-ed than a track that stands on its own.

It’s not this song’s fault that the extended version of Speak Now has songs called both “Mine” and “Ours” — and while “Ours” is good … well, it’s no “Mine.” Still, even if this song never rises above cuteness, it is incredibly cute. I think Dad’ll get over the tattoos.

As with “We Are Never Ever Getting Back Together,” “Bad Blood” represents a peak of Swift’s Max Martin era, when she was turning out perfectly crafted pop earworms that felt like they’d been designed in some subterranean Scandinavian laboratory. What she gained in hookiness, she lost in humanity. The schoolyard-chant melody here sounds like carved into a granite cliff face, 60 feet high. The lyrics indulges the worst habits of mid-period Swift — an eagerness to play the victim, a slight lack of resemblance to anything approaching real life. Still, “Bad Blood” is ranked this high in honor of its historical importance; its video is an artifact of the era when Swift was collecting famous friends like they were Pokémon. It’s not worth getting into the spat with Katy Perry that inspired the track, except to note that Swift’s assumption that she held the moral high ground in every celebrity feud would be the source of much trouble in the future.

The first time I heard this, I thought it was one of the best things Swift had ever done — so much so that, at the moment she contemplates forgiving a hater, then bursts into an incredulous guffaw, I laughed out loud too. What can I say? It was late, and I was tired. I suspect Swift liked it just as much since she made it the epic finale for her Reputation live show. History hasn’t vindicated either of us, but the positive memories remain.

When people say TTPD needed an editor, songs like this are what they’re talking about. She’s got a great idea: using religious imagery while fantasizing about an affair that technically hasn’t happened yet and wondering if that still counts. But first-draft clunkiness abounds, especially in the bridge. I can picture the red pen: “‘I choose you and me, religiously’ — Do we need this?”

Swift had two shots at an Oscar nomination in 2022. The one she really wanted was a Best Live Action Short nod for her “All Too Well” video. (Which is … fine. If a film student turned it in you wouldn’t advise them to become a dentist, but you wouldn’t hand them an Oscar, either.) The other was Best Original Song for her closing-credits ballad from Where the Crawdads Sing, which is slightly less potent than earlier Southern Gothic efforts like “Seven,” but is still a million times better than the movie itself, which is fake, fake, fake. Unfortunately, Swift’s long wait for her first Oscar nom would continue. Original Song went to the exuberant “Naatu Naatu,” while the mawkish An Irish Goodbye won Live Action Short.

A vault track that sounds like she put all of 1989 in a blender and went BRRRRR. The preponderance of “say,” “stay,” and “go” in the lyrics points to a shared font of inspiration with “All You Had to Do Was Stay.”

A divorce ballad finished only a few days before Evermore’s release. Swift has written this type of cathartic breakup song before, and, attractive piano melody aside, not much separates this one.

When we heard Swift was collaborating with Lana Del Rey, fans expected a “Lady Marmalade”–level phenomenon. Instead, the original version of “Snow on the Beach” relegated Del Rey to a spectral presence in the distance. As a make-good, Swift reworked the song for the Til Dawn edition of Midnights, giving Lana a verse that adds some sorely needed dramatic heft. The title now reads, “feat. More Lana Del Rey,” which is hilarious.

Had this vault track been released in 2010, it would instantly have been the most adult song in Swift’s repertoire; the imagery is more sensual than anything she released before Red. Of course, had it come out in 2010, I don’t think it would have sounded much like the version we hear on the rerelease, which has an ’80s sharpness Swift wouldn’t add to her sound until years later.

I’ll take “Poetry in Motion” for $200, please. Here, Swift compares herself and her messy, tumultuous fame to one of the most famously cursed animals in western literature. But if she can give Shakespeare a happy ending, she damn sure can give Coleridge one as well. The albatross saves the day in the end!

Pitch-shifted vocals are to Midnights what cheerleader choruses were to Lover.

A woozy if slightly anonymous love song that comes off as a sexier “Take Me to Church.” [A dozen Hozier fans storm out of the room.]

Even as a pop prodigy who had experienced nothing but an unbroken string of successes, Swift was obsessed with her own inevitable downfall. That’s why she worked so hard to remain at the top, and why her 2016 cancellation amid the Kanye West/”Famous” fracas affected her as intensely as it did: Like a figure from a Greek tragedy, she saw it coming yet was unable to prevent it. This vault track continues the gothic strain that crept into Swift’s work around Speak Now, with special guest Hayley Williams adding a fitting level of melodrama. She would later repurpose the title phrase for the opening line of 2017’s “Call It What You Want.”

Put aside the quotations from Taken and the greatest hits of Michael Bublé and this is a fun little genre pastiche. Especially in the twang of the production, which sounds like it comes straight out of an Old West saloon.

“Closure” features one of the bigger production swings of Swift’s quarantine era, an industrial drum track that sparks up a song that otherwise remains subdued. (I’ve seen the percussion compared to Nine Inch Nails, but the Postal Service feels more her wavelength.) It works better than Swift’s other capital-C choice: her decision to sing the chorus in a British accent. You wot?

Speak Now’s “Never Grow Up” was an ode to childhood that showed off teenage Swift’s prodigious skill at distilling powerful emotions from a few simple images. As a 30-something unsure if motherhood is on the table, her follow-up is less romantic. Now, she notices how the child’s innocent world of imagination is a construct carefully maintained by adults. “You have no idea,” she tells the kid. “All this showmanship, to keep it for you in sweetness.” A little boy playing with dinosaurs inspires a song about the lies we tell one another — in the least derogatory way possible, this is the music of a depressed person.

The first sign that Folklore would not be an album you put on in the background while doing something else, this plodding Bon Iver duet broke my patience a few times. Only when I got my headphones and really listened to it did I pick up the jagged edges in the breakup ballad. “I can see you staring, honey / Like he’s just your understudy” is an underrated blood-drawer. Rest in peace to co-writer “William Bowery,” who will probably never be heard from again.

The title is a little misleading: This is not a hater-baiting anthem, but rather a dreamy ballad exalting in the feeling of dating a man everyone else covets. Docked five spots for biting “drunk in love.”

Swift has a built-in ability to take in everything she sees. To commemorate Fall Out Boy’s influence on her Speak Now–era songwriting, she brought the band in to collaborate on this vault track. Together they do a more than capable version of FOB’s big rock sound with Swift singing the hell out of that huge, anthemic hook.

Had Swift never moved to Nashville, this pop-punk confection sounds like something she might have released in the late aughts. I know some fans think it’s silly, but they played it at my brother’s wedding so I couldn’t possibly dislike it.

This one reminds me of Joanna Hogg’s Souvenir films, in part because Swift literally says the word souvenir in it but also because Swift name-dropped them during her Oscars campaign. (Joe Alwyn had a small role in the second one.) Both the song and films are about a young woman mining a troubled relationship with an older man as creative inspiration. Reading between the lines, this appears to be a reference to Swift’s experience revisiting her Red romance while directing the ten-minute “All Too Well” video. Her version went smoother than in the movies, but do I detect a hint of ambivalence when, after turning her life into fodder for her art, Swift concludes, “The story wasn’t mine anymore”?

This duet with Chris Stapleton is another acid-penned kiss-off to a Jake Gyllenhaal type. All in good fun, though she lays on the reverse-snobbery a bit thick in lines like “I was raised on a farm; no, it wasn’t a mansion.” Girl, your dad worked for Merrill Lynch.

The best vault track from the Fearless rerelease, written all the way back in 2005 and given a tasteful country sheen with the help of Maren Morris’s backup vocals. It’s additional proof that, even as a high-schooler, she had the lyrical skills of a seasoned professional, displaying a deft hand at metaphor here. One has to wonder if the reason it was never released is that, given Swift’s squeaky-clean image at the time, the chorus was ripe for misinterpretation.

A trip down memory lane to the 1989 era — literally, in the case of the “Out of the Woods” interpolation but also in the vibes and lyrical callbacks. I like that she adds her friends’ cheers into the chorus the second time around.

The breeziest and least complicated of Swift’s guy-standing-on-a-doorstep songs, which contributed to the feeling that 1989 was something of an emotional regression. You probably shouldn’t take it as an instruction manual unless you’re Harry Styles.

The Tragedy of Taylor A. Swift, in which the author worries that the very thing that makes her desired by millions of strangers also dooms her to be forever unlovable in real life. Of all Swift’s varied post-folklore modes, I like her best when she gets into dark-night-of-the-soul territory.

Young Swift enjoyed imagining the inner lives of older couples she idealized. This one’s about her grandparents, Marjorie and Robert. While songs like “Starlight” spin off quickly into fantasy, the personal connection here grounds “Timeless” in something approaching real life.

This reverb-drenched track has garnered comparisons to the Sundays and Sixpence None the Richer, and the ’90s pastiche is spot-on, though unfortunately a tad sleepier than its forebears. Question for the group: Did she get the title from Sarah McLachlan or Everything But the Girl?

No attempts of universality here — this trip-hop song about trying to find a place to make out when you’re a massive celebrity is only relatable to a couple dozen people. No matter. As a slice of gothic pop-star paranoia, it gives a much-needed bit of edge to 1989. Bumped up a couple of spots for the line about vultures, which I can only assume is a shout-out.

Do you need subtext? This unguarded track surfs along with its heart on its sleeve, plus a languid saxophone and a few great turns of phrase. (“I got wasted like all my potential.”) The climax sneaks up on you like a moment of clarity.

This is widely assumed to be a memorial for a high-school friend who died too young. Grief is the animating emotion behind many of Swift’s best songs, and faced with a different type of loss than the one she usually writes about, her emotions ring true.

Written in collaboration with Big and Rich’s John Rich, which may explain how stately and mid-tempo this one is. (There’s even a martial drumbeat.) Here, she’s faced with a choice between a too-perfect guy — he’s close to her mother and talks business with her father — and a tempestuous relationship full of “screaming and fighting and kissing in the rain,” and if you don’t know which one she prefers I suggest you listen to more Taylor Swift songs. Swift often plays guessing games about which parts of her songs are autobiographical, but this one is explicitly a fantasy.

“This Is Why We Can’t Have Nice Things,” “Hits Different,” “Down Bad” — slang is the one thing Swift does more unnaturally than F-bombs. Still, she’s in her Close Encounters era on this one, the latest entry in the hallowed tradition of pop songs about falling in love with an alien. She’s giving Radiohead. She’s so Katy and Kanye coded. It is, I fear, kind of a slay. No cap.

This one dates back to Swift’s high-school days and was destined for obscurity until fans fell in love with the live version. After what seems like a lot of tinkering, “Sparks Fly” finally got a proper studio release on Swift’s third album. Because of this, Swifties treasure it dearly, but I prefer her other “kissing in the rain” songs.

Borrowing a phrase from Emily Dickinson, Swift mourns a lost relationship (maybe a breakup, a death, or possibly a miscarriage.) It’s sparse, but her vulnerable vocals sell it.

Had Swift lacked the charisma to become a star herself, I like to think she would’ve become one of those Nashville jobbers who lurks behind the scenes writing radio hits for other artists. This twangy ballad about con artists who fall in love feels like the work of that alternate-reality Swift. Fortunately, the lived-in cynicism of the lyrics belies the tune’s anonymous qualities.

Much of the pleasure here comes via a sample from a Toronto music academy, a steel-drum-and-chorus beat that sounds like nothing else in Swift’s discography. The schoolyard vibe fits the playground-romance lyrics; I assume any resemblance to the plot of Carol is accidental.

The clear standout of Swift’s Christmas album, with an endearingly winsome riff and lyrics that paint a poignant picture of yuletide heartbreak. If you’ve ever been alone on Christmas, this is your song.

An easy, breezy intro destined to end up in Spotify’s Favorite Coffeehouse playlist.

Learned helplessness, as expressed through doll metaphors and leftover synths from 1989. It’s sadder than you’d think: On “You should have seen him when he first got me,” she really does sound like the mom to a 7-year-old.

After years of being dinged for staying apolitical in her art, Swift takes her first step into the arena here, reframing the 2016 election through the high-school environment that provided so much of her early inspiration. It’s an ambitious conceit that I don’t think works 100 percent, but I appreciate the big swing. Knocked a few spots for featuring the cheerleader chorus on Lover that finally broke me.

Written in a rush of emotion near the end of recording for the debut, what this early single lacks in nuance it makes up for in backbone. I appreciate the way the end of each verse holds out hope for the cheating ex — “given ooonnne chaaance, it was a moment of weeaaknesssss” — before the chorus slams the door in the dumb lunk’s face.

A slight duet with Ed Sheeran that finds them both running on autopilot through some perfectly pleasant territory. That she could afford to keep a song like this in the vault says something about the quality of work she was turning out during the Red era.

A single that successfully makes the case for Lana Del Rey as the most influential pop artist of the past decade. Neither Swift nor special guest Post Malone embarrasses themselves, but it’s pitched at a woozy mid-tempo that’s my musical Ambien (I enjoy it in the moment but have a very hard time remembering it after it’s over).

An ultra-rarity — only available to those who attended Swift’s Eras Tour stop in New Jersey — which develops the medical metaphor first employed on Folklore’s “Epiphany.” Here she compares the slow death of a relationship to a patient losing consciousness, a successful addition to Midnight’s bevy of self-loving/self-hating recriminations. Also bears the distinction of possibly being the first song of the post-Alwyn era, as the line “I wouldn’t marry me either” was an irresistible hint for the gossip-hounds.

Like “22,” an attempt at writing a big generational anthem. Being left off the album proper suggests Swift didn’t think it quite got there, though it did its job of extending the singles cycle of 1989 a few more months. Despite what anyone says about “Welcome to New York,” the line here about waiting for “trains that just aren’t coming” indicates its writer has had at least one authentic New York experience.

What initially seems like another ode to Alwyn reveals itself, Owl Creek Bridge–style, to actually be the fantasy of an unlucky-in-love narrator. The throbbing chorus doesn’t really do it for me, but I appreciate the swooning imagery in the verses, as visions of dinner parties and vacations fade away into “the gray of my day-old tea.” Bumped up a spot for the reminder that Swift is an Iggles fan.

It took me a while to warm up to Joe Alwyn as a muse. I just didn’t find the guy compelling, and I missed the dramatic sweep of Swift’s earlier romances. With a little distance, I see now that that was the point: The understated relationship depicted in Reputation and elsewhere was a respite from everything going on in Swift’s public life. When millions of listeners are convinced you’re a horrible person, finding one person who knows you’re not is a godsend. As the years went by, tracks like “Cornelia Street” gave the Alywn era its own lore, and when it ended, I was more broken up about it than I ever expected. But I still can’t really get into this one.

The best of Swift’s songs idealizing someone else’s love story (see “Starlight” and “Mary’s Song”), this bonus track sketches Jack Antonoff and Lena Dunham’s relationship in flashes of moments. The production and vocals are appropriately restrained — sometimes, simplicity works.

Low-key one of the most depressing songs she has ever released: a fairy tale about how female genius is packaged and sold by male gatekeepers. The lucky ones who get picked must work to stay “dazzling” lest they lose their allure, and true stardom comes at the cost of their humanity. They’re deified yet destined to be replaced. Ever the skeptic, Swift can’t help but imagine the day it happens to her: A future starlet is compared to Taylor Swift, but the suits assure her, “You’ve got edge she never did.”

I have trouble doing things with intention. I get nervous about choosing the wrong path, delay until it’s almost too late, and then make a haphazard decision at the last minute. One thing I admire about Swift is she does not appear to suffer from this problem. To close out Midnights, she eschews her typical quiet summation in favor of a joking-but-not-really examination of her obsession with control. “No one wanted to play with me as a little kid / So I’ve been scheming like a criminal ever since / To make them love me and make it seem effortless.” Is it parody masquerading as confession, or confession masquerading as parody? All I know is there are few moments on Midnights more cathartic than when the synths hit in the pre-chorus.

One fascinating element of Swift’s 2020s output is the bevy of songs in which this successful, respected, and objectively beautiful musician imagines herself as an ogre everyone hates. People tend to look askance at this, seeing it as another instance of her victim complex. But they miss the playful element: that Swift’s having fun trying on a Disney-villain costume. I enjoy her Evil Taylor persona on this one, even if it is a slight retread of “Mad Woman.” She leans into the horror with monster imagery (“So I leap from the gallows and I levitate down your street”) and snarls at the ungrateful kids who won’t stop posting about her private jet: “You wouldn’t last an hour in the asylum where they raised me!”

The notion of Folklore as Swift’s “goth album” didn’t extend much further than the promo imagery and this side-two spooker, a haunting evocation of female rage. It gives us the unrepentant knife-twisting that Reputation only gestured at, and it gets 13 percent more fun if you pretend she’s saying, “Mouth-fuck you forever.”

The kind of plaintive breakup song Swift could write in her sleep at this point in her career, with standout guitar work and impressive vulnerability in both lyrics and performance.

Swift returns to the isolated woodland compound where she left Bon Iver after “Exile” and whaddya know, he still works! This one’s less turgid than its predecessor, and if the duo’s vocal parts feel uncomfortably stitched together at times, at least they come together for a rousing back-and-forth climax.

There’s more than a little Sufjan Stevens in the way Swift shoots up into falsetto at the end of each second line. “A dwindling mercurial HIGH!” Though this is one of the implicitly fictional songs on Folklore, it’s a signpost of Swift’s increasing comfort with playing the bad guy in romantic relationships.

The deluxe edition of Speak Now features both U.S. and international versions of some of the singles, which gives you a sense of how fine-tuned Swift’s operation was by this point. My ears can’t quite hear the difference between the two versions of this exuberant breakup jam, but I suspect the U.S. mix contains some sort of ultrasonic frequencies designed to … sorry, I’ve already said too much.

Have you ever gone back and read any of those blog posts about Swift from 2016? People were zooming in on Notes App screenshots, searching for hidden pixels that supposedly proved her perfidious nature. Of course she went a little crazy and recorded a super-defensive album about it — anyone would! The best way to get a sense of Swift’s headspace in the months after her cancellation is to listen to this Reputation deep cut, which overflows with aggression and paranoia. Is that a raga chant? Are those fucking gunshots? Docked a spot or ten for “They’re burning all the witches even if you aren’t one,” which doth protest too much, but bumped up just as much for Swift’s first on-the-record “shit.”

Swift’s songs where she’s romanticizing childhood come off better than the ones where she’s romanticizing old age. (Possibly because she’s been a child before.) This one is so well-observed and wistful about the idea of children aging that you’d swear she was secretly a 39-year-old mom.

A popular conspiracy theory says the vault tracks on the Taylor’s Version releases aren’t actually as old as Swift claims. More evidence comes in this little sketch, the shortest song she’s ever put out, which is so bitingly specific you can’t believe it’s not about Jake Gyllenhaal. But if it is indeed about Harry Styles, then why is she referencing things that happened in 2018? Whenever they were written, the lyrics here are meaner than anything Swift was willing to say on the record about Styles in 2014, though you can tell they’re coming from a place of genuine hurt. The rising falsetto in the chorus should be trademarked at this point.

You’d never call Swift a genre deconstructionist, but her best work digs deeper into romantic tropes than she gets credit for. In just her second album, she and Rose gave us this clear-eyed look at the emptiness of symbolic gestures, allegedly finished in a mere 45 minutes. Almost left off the album, but saved thanks to Shonda Rhimes.

Like “Betty” on Folklore, an effortless channeling of Swift’s old sound on a fictional tale of teenage romance. According to the author, “Dorothea” canonically takes place in the same universe as Folklore’s love-triangle trilogy, though the melodrama has been turned down a few notches. It’s a wistful recollection of the narrator’s high-school relationship with the title character, who skipped town, became a big star, and never looked back. The lyrics are folksy and self-effacing, as Swift dreams of a reunion while constantly reminding herself that it could never happen. But she can’t quite stop herself from holding out hope: “If you’re ever tired of bеing known for who you know / You know that you’ll always know me.” The optimism might not be too misguided: According to “‘Tis the Damn Season,” these two haven’t seen the last of each other.

Just like the melody to “Yesterday” and the “Satisfaction” riff, the high-pitched “Stay!” here came to its writer in a dream. Inspiration works in mysterious ways.

This airy slow jam about losing yourself in love following a scandal turns out surprisingly sexy, though the saltiness in the verses (“all the liars are calling me one”) occasionally betrays the sentiment.

A portrait of high-school heartbreak, equal parts mundane — no adult songwriter would have named the crush “Drew” — and melodramatic. It’s also the best example of Swift and Rose’s early songwriting cheat code, when they switch the words of the chorus around at the end of the song. “It just makes the listener feel like the writer and the artist care about the song,” Rose told Billboard. “That they’re like, “Okay, you’ve heard it, but wait a minute — ’cause I want you know that this really affected me, I’m gonna dig the knife in just a little bit deeper.’” (“Teardrops” ended up inspiring a moment that could have come straight out of a Taylor Swift song, when the real Drew showed up outside her house one night. “I hadn’t talked to him in two-and-a-half years,” she told the Washington Post. “He was like: ‘Hey, how’s it going?’ And I’m like: ‘Wow, you’re late? Good to see you?’”)

Sue me — I think this Travis Kelce anthem is cute. In the context of TTPD’s second-half torpor, the dreamy ’90s alt-rock vibes have an effervescent effect. All I’ll say about lines like “Touch me while your bros play Grand Theft Auto” is that people are taking them too literally.

Someone on Twitter called TTPD “the midpoint between music and a podcast” in the way its rhythms borrow more from conversational patterns than traditional song structure. It’s most apparent on this track, which is the album in miniature: repetitive, overwritten, and coasting too much on lore — and yet impossible to deny completely. The hook lingers less than the gossip, but at least it’s fun to imagine her eating junk food and chatting about B-list pop singers.

“We good to go?” For many American listeners, this was the first introduction to a redheaded crooner named Ed Sheeran. It’s a sweet duet and Sheeran’s got a roughness that goes well with Swift’s cleaner vocals, but the harmonies are a bit bland.

The millennial tendency to loudly decry a situation while obscuring one’s own agency: I have lost my patience for it. So I appreciate the honesty in this advice to younger listeners in which Swift reveals the secret trials of her 20-something superstardom — “I hosted parties and starved my body / Like I’d be saved by a perfect kiss” — but also notes, “I took the money.” The lesson that nothing is ever as good as it seems from the outside is hard-earned, even if the conclusion, to live in the moment, is a little pat.

Probably too noncommittal to be a first single, but man, imagine how different the buzz for Lover would have been had this winning song been our introduction to the era. As it is, it’s a fitting leadoff track for the album proper, as Swift puts the Reputation drama behind her with a sprightly ode to the joy of indifference. In a fun twist, the utter lack of negative emotion here makes this one of Swift’s coldest kiss-off songs. Elie Wiesel was right.

Co-written with Imogen Heap, who contributes backup vocals. This is 1989’s big end-of-album-catharsis song, and the water imagery of the lyrics goes well with the drip-drip-drip production. I’d be curious to hear a version where Heap sings lead; the minimalist sound might be better suited for her voice, which has a little more texture.

In which an artist known for worldly concerns wades into the realm of the spiritual. The song’s addressed to Swift’s late grandmother Marjorie Finlay, an opera singer who passed away in 2003. But that doesn’t mean she’s gone, Swift says: “What died didn’t stay dead / You’re alive in my head.” In fact, she can hear her grandma singing to her right now, at which point we hear the real Marjorie crooning in the background — a conjuring both haunting and strangely comforting.

Ostensibly written about Swift’s experiences touring with her band, but universal enough that it’s been taken as a graduation song by pretty much everyone else. Turns out, adolescent self-mythologizing is the same no matter where you are — no surprise that Swift could pull it off despite leaving school after sophomore year.

The normal rules of Taylor Swift album sequencing say this lo-fi love song should have been the last track on Folklore, but I guess that’s 2020 for you. More clearly autobiographical than much of the album, Swift apologizes to her lover for the stress that comes with dating one of the world’s most famous women. There’s a world where that comes off as an insufferable flex, but her unassuming authenticity keeps it far away from humblebrag territory.

Workmanlike pop in the 1989 mode. Lyrically, this is kind of the same song as “Me!” but rewritten to be less annoying. Swift isn’t talking about how great she is just for the sake of it but to remind an inattentive partner what he’s taking for granted. Like the Beatles and diamond rings, precious gems are the luxe imagery she keeps close whenever she needs a metaphor.

It always gets me when Swift shifts from singing “You said I’m the love of your life” to speaking “about a million times.” If she were a pitcher, this would be her changeup, the sudden downshift that keeps the listener off-balance.

Do you ever look back on a crisis that used to consume your entire life and find yourself shocked by how small it seems in retrospect? That’s where Swift’s at in this breezy electro-pop track, which sums up years of public drama with a terse, “Long story short, it was a bad time.” Reputation found Swift playing at being over it while clearly not being over it; here, the sentiment finally feels genuine. I think I speak for everyone, though, when I say we’d be fine with this being her final word on the subject.

An effervescent banjo-driven love song. I get a silly kick out of the gag in the chorus, when Swift’s voice leaps to the top of her register every time she says “jump.”

Swift brought out the Dixie Chicks for this soft acoustic ballad inspired by her mother’s cancer recurrence. Despite the star-studded lineup, the song is simple, sincere, and affecting, and Swift’s vocals infuse the heartbreaking details with just the right amount of childish naivety: “You’ll get better soon / ’cause you have to.”

Amid the generally positive reception for Midnights, some critics took issue with Swift’s falling back on the Antonoffian sound she developed on 1989 rather than continuing the experiments of her pandemic recordings. There’s no denying Midnights’ lyrics cut less deep, but it’s not a complete backslide: In tracks like this one, she navigates complicated emotional terrain, exploring the way the fame industry has no frame of reference for an unmarried, childless woman in a long-term relationship. “All they keep asking me is if I’m gonna be your bride,” she sings. “The only kinda girl they see is a one-night or a wife.” She’s had it with the “1950s shit they want from me,” but there’s a tiny part of her that sees the appeal: The title comes from a bit of ’50s slang she picked up from Mad Men.

An epic account of being stood up that makes a terrible birthday party seem like something approximating the Fall of Troy. If you’re the type of person who stays up at night remembering every inconsiderate thing you’ve ever done, the level of excruciating detail here is like a needle to the heart.

So intimate it’s almost uncomfortable: Just Swift, a piano, and quiet strings, bathed in religious imagery and nods to private tragedies we’ll probably never know about.

At the time, this one was billed as a big step for Swift: the first song where she’s the bad guy! Now that the novelty has worn off “Back to December” doesn’t feel so groundbreaking, but it does show her evolving sensitivity. The key to a good apology has always been sincerity, and whatever faults Swift may have, a lack of sincerity has never been one of them.

Swift hadn’t yet lived through a public-enemy cycle when she wrote this self-aware ballad in the spring of 2012, but she was perceptive enough to see what was coming: “Shoot you down, and then they sigh / And say, ‘She looks like she’s been through it.’” There’s a vulnerability here that presages her later songs, as 22-year-old Swift works through her anxiety about one day losing the currency of youth, wondering what it’ll be like when she’s the legacy act all the bright young things are name-dropping. The version she finally recorded proved it doesn’t have to be so sad: Nine years later, she was generous enough to share the mic with one of those acolytes, Phoebe Bridgers.

Evermore kicks off with a visit to the world’s most melancholy coffeehouse. “Willow” is a love song, but it’s so prickly and suspicious it doesn’t always sound like one. There’s a striking sharpness to this track, both in the fingerpicked guitar line and in Swift’s plea for her man to “take my hand / wreck my plans.” Docked five spots for the “’90s trend” line, which feels like something she threw in because she wanted to put it on a T-shirt.

Swift’s separation from her old label Big Machine gets a dramatic breakup anthem worthy of the years they spent together. She concocts a ghostly fantasy about watching your enemies wail at your funeral; the operatic grandeur of Antonoff’s production is only too apropos. Surely it’s a coincidence that the intro sounds a bit like a song from one of Swift’s other old enemies?

The Atlantic called 1989 Swift’s “Tinder record”: No other album of hers is as suggestive of late-night texts and strangers’ naked limbs. This vault track is the morning-after hangover, as Swift takes stock of a fling in which she was never sure where they stood, now that they’re both fucking other people. From the complications that come from both parties being equally famous, to the lyrical Easter eggs about iconic paparazzi photos, and the overall sense of lying alone on the couch replaying everything in your head, this is classic Swift. The audible callbacks to “Out of the Woods” are the cherry on top: the same unsteady feeling from two points in the same relationship, one from the high, the other from the wreckage.

Many fans believe this song is about Emma Stone, who befriended Swift around the same time the latter was working on Speak Now. Whether that’s true or not, this ballad is Swift at her most observant, an effortlessly poetic character study of a friend falling in love for the first time. Warning: From now on, any time an Emma gets married, you’re going to hear this song — probably for the rest of your life.

Alt-rock ’90s guitars soundtrack this scathing song about an older guy who may or may not have half a dozen Grammys. He was a “promising grown man”; she was a child he “got to wash [his] hands” of. This is Swift’s strongest vocal performance on Midnights, rising with the exhilaration of her “dance with the Devil” and breaking in anguish when she pleads, “Give me back my girlhood, it was mine first.” Your heart breaks with her.

This chugging rocker nails the feeling of reconnecting with an ex and romanticizing the times you shared, and it livens up the back half of Red a bit. Probably ranked too high, but this is my list and I’ll do what I want.

If I didn’t know better, I’d say this one was a leftover from the Reputation sessions. (It’s not; co-writers Louis Bell and Frank Dukes didn’t work on that album.) Still, the airy vibe and heavy drums recall Swift’s 2017 output with the fear and paranoia swapped out for honesty and accountability.

If we didn’t rank all of Swift’s mediocre holiday songs, the good ones would feel far less special. The best is this blue-Christmas anthem all about the somber ritual of hooking up with your hometown ex over the holidays. Per Swift, the narrator is the movie star from “Dorothea,” which adds a frisson of class tension to the push-pull of the romance.

A breakup song is animated with anger; a divorce song is exhausted, suffused with the weight of years. On TTPD, one of our finest purveyors of the former finally turns her hand to the latter. (As Liz Phair proves, you need not have been married to write a divorce song.) She’s not only going through a heart-wrenching split on this one but also girding for the “empathetic hunger” she’ll have to face once the outside world hears about the separation. Something celebs have to worry about more than regular people, sure, but it’s still relatable to anyone with a social circle.

Swift has rarely been so tactile as on this intimate ballad, seemingly constructed entirely out of sighs.

The rest of the band plays it so straight that it might take a second listen to realize that this song is, frankly, bonkers. First, Swift sneaks into a wedding to find a bridezilla, “wearing a gown shaped like a pastry,” snarling at the bridesmaids. Then it turns out she’s been uninvited — oops — so she decides to hide in the curtains. Finally, at a pivotal moment she stands up in front of everyone and protests the impending union. Luckily the guy is cool with it, so we get a happy ending! All this nonsense undercuts the admittedly charming chorus, but it’s hard not to smile at the unabashed silliness.

There’s an apocryphal story, purportedly from someone who dated Swift in the Fearless era, that she went into a mode he called “Taylorbot” whenever she had to deal with fans and the media. You need not believe this is true to figure that a person who became world famous at a vulnerable age might have had to create extremely strong defense mechanisms to handle it. Some of my favorite songs on TTPD are the ones in which Swift looks back on spending half her life as “Taylor Swift” and thinks, That really fucked me up, didn’t it? She turns that realization into mordant fun on this one, in which she reveals she spent much of her record-breaking Eras Tour secretly miserable. “I’m so depressed I act like it’s my birthday every day,” she sings over some of the album’s peppiest production — an obvious joke but a good one. The most uncomfortable moment of revelation comes in the closing button when Swift takes a victory lap over how well she hid her true self from the public: “Try to come for my job.” She’s terrifying.

An unofficial sequel to “Red” in which the vibrant hues of youth have faded to more muted tones. It’s the dull ache of looking back on a relationship that didn’t play out the way it should have and for which you’ll never have closure. The details have downshifted too: On “Red,” we had a new Maserati; here, a “roommate’s cheap-ass screw-top rosé.” (A phrase as beautiful to me as “cellar door.”) Docked a few spots for featuring roughly the same backing track as “King of My Heart.”

Here, the Alwyn era comes to an end, not with a bang but with a whimper. Fans who expected a full-throated denunciation were surprised to hear only resigned acceptance at a relationship that had run its course. Ranked above the similar “How Did It End?” for its bevy of quiet daggers: the image of “two graves, one gun” and her shiver at giving her ex “all that youth for free.”

A song about a young woman who rejects a proposal from her nice, rich boyfriend that plays like a story J.D. Salinger never wrote. Swift covered similar territory in “Back to December,” but the intervening decade has seen her expand her facility for characterization: This time around, we get glimpses not just of the self-conscious and self-deprecating narrator, but also the boyfriend and his family, too.

Another collaboration with Martin and Shellback, another absurdly catchy single. Still, there’s enough personality in the machine for this to still feel like a Taylor track, for better (“breakfast at midnight” being the epitome of adult freedom) and for worse (the obsession with “cool kids”). Mostly for better.

Someone pointed out that this is functionally an emo song, which is probably why I dig the throwback vibe. On an album where the choruses are generally lacking, she finally gives us a big shout-y hook. You can imagine aging millennials at her concerts going nuts: “Old habits die SCREEEEAAAAAMMMMIIINNNG.”

Who knew so many words rhymed with Stephen? They all come so naturally here. Swift is in the zone as a writer, performer, and producer on this winning deep cut, which gives us some wonderful sideways rhymes (“look like an angel” goes with “kiss you in the rain, so”), a trusty Hammond organ in the background, and a bunch of endearing little ad-libs, to say nothing of the kicker: “All those other girls, well they’re beautiful / But would they write a song for you?” For once, the mid-song laugh is entirely appropriate.

“I’ve never named names,” Swift once told GQ. “The fact that I’ve never confirmed who those songs are about makes me feel like there is still one card I’m holding.” That may technically be true, but she came pretty dang close with this seven-minute epic. (John Mayer said he felt “humiliated” by the song, after which Swift told Glamour it was “presumptuous” of him to think that the song his ex wrote, that used his first name, was about him.) She sings the hell out of it, but when it comes to songs where Swift systematically outlines all the ways in which an older male celebrity is an inadequate partner, I prefer “All Too Well,” which is less wallow-y. I’ve seen it speculated that the guitar noodling on this track is meant as a parody of Mayer’s own late-’00s output, which if true would be deliciously petty.

An amusing curio about Rebekah Harkness, the eccentric widow of an oil scion, who built the Rhode Island mansion Swift would purchase (all cash) in 2013. She has fun constructing parallels between herself and Harkness — their neighbors hated them! — and a last-chorus switcheroo makes the comparison explicit. It’s a crucial dose of levity on Folklore, and a chance for Swift to develop the album’s matrilineal themes, though I can’t help wishing for a less peppy production that would bring some of that “Mad Woman” energy.

Swift was far from the first female pop star to pitch-shift her vocals down to an artificially low register. (For one, Beyoncé had her beat by almost a decade.) It’s a striking note to kick off this remembrance of a long-forgotten relationship Swift had to abandon for the sake of her ambition. “He wanted a bride; I was making my own name,” her deeper voice sings, flipping the script both sonically and socially. On Lover, she wondered what life would be like if she were the man. Here, she realizes that, like Cher, she always has been.

If you by chance ever happen to meet Taylor Swift, there is one thing you should know: Do not, under any circumstances, call her “calculating.” “Am I shooting from the hip?” she once asked GQ when confronted with the word. “Would any of this have happened if I was? … You can be accidentally successful for three or four years. Accidents happen. But careers take hard work.” However, since the title of her first single apparently came from label head Scott Borchetta — “I told Taylor, ‘They won’t immediately remember your name, they’ll say who’s this young girl with this song about Tim McGraw?’” — I think we’re allowed to break out the c-word: Calling it “Tim McGraw” was the first genius calculation in a career that would turn out to be full of them. Still, there would have been no getting anywhere with it if the song weren’t good. Even as a teenager, Swift was savvy enough to know that country fans love nothing more than listening to songs about listening to country music. And the very first line marks her as more of a skeptic than you might expect: “He said the way my blue eyes shined put those Georgia pines to shame that night / I said, ‘That’s a lie.’”

A song that takes the rest of TTPD by the shoulders and shakes it. Dramatic and overwrought — that synth hit is size-72 Impact font — but unlike “No Body, No Crime,” it doesn’t feel like dress-up. The atmosphere is noirish enough to convince me Swift really could murder a man and get away scot-free. She gets eaten up by Florence Welch in the outro, but who doesn’t?

Originally the title track for Swift’s third album until her label told her, more or less, to cut it with the fairy-tale stuff. It’s a glittery ode to a meet-cute that probably didn’t need to be six minutes long, but at least the extended length gives us extra time to soak up the heavenly coda, with its multi-tracked “Please don’t be in love with someone else.” If you ask a Swiftie, this one should be in the top 10.

Another collaboration with the late William Bowery that pitches domestic comfort as a refuge from the harsh world outside. Sweetly syncopated vocals bounce across a winsome piano line that’s as cozy as a big wooly blanket, making the subtext literal. The Alwyn era gave us a lot of songs like this, and I like almost all of them.

Swift’s second No. 1 was greeted with widespread critical sighs: After the heights of Red, why was she serving up cotton-candy fluff about dancing your way past the haters? (Never mind that Red had its own sugary singles.) Years later the purpose of “Shake It Off” is clear: This is a wedding song, empty-headed fun designed to get both Grandma and Lil’ Jayden on the dance floor. Docked ten or so spots for the spoken-word bridge and cheerleader breakdown, which might be the worst 24 seconds of the entire album.

Swift’s collaboration with folk duo the Civil Wars is her best soundtrack cut by a country mile. Freed from the constraints of her usual mode, her vocals paint in corners you didn’t think she could reach, especially when she tries out a high-pitched vibrato that blends beautifully with Joy Williams and John Paul White’s hushed harmonies. Almost a decade before Folklore, this was the first time she’d ever been spooky.

Online, Swifties live in a collective unreality powered by their own imaginations. While this is not how I prefer to experience her music, it’s basically harmless (though if they start talking about an imminent race war, watch out). One viral theory supposes that, shortly before her career was upended in 2016, Swift was gearing up to release a new album with a rockier sound called Karma, which she subsequently scrapped in the wake of the backlash. Whether this single is a hint that Karma is indeed real or simply a nod to Swift’s well-known affinity for the concept, it’s proof that her seemingly effortless skill at whipping up pop confections hadn’t abated during her years in the woods. The lyrics are nonsense — what’s all this about spiders? — but I like its breezy stutter step of a hook.

During the misbegotten rollout for Reputation, I remember thinking “Gorgeous” righted the ship by not being completely terrible. I wasn’t giving it enough credit. Max Martin and Shellback pack the track with all sorts of amusing audio doodads, and while the melody is a little too horizontal, the hook is undeniable. I prefer the first draft, which is slightly more open and real, but in either case, the flirting is fun.

The folkiest track on Folklore serves up a southern-gothic vision of childhood where wild innocence brushes past darkness that’s only apparent in retrospect. Once again, we’re in the realm of memory as the narrator reminisces about a friend from a troubled home — someone she once cared about but whose face has faded from her mind — then muses on how they might remember her. She experimented with new perspectives elsewhere on the album; here, she tries out a whole new voice, debuting a McLachlan-esque croon, almost as if the song’s being sung by two different people.

A collage of lines pulled from the blog of Maya Thompson, whose 3-year-old son had died of cancer, this charity single sees Swift turn herself into an effective conduit for the other woman’s grief. (Thompson gets a co-writing credit.) One of the most empathetic songs in Swift’s catalogue, as well as her most reliable tearjerker.

The guiding principle on much of Red seems to have been to throw absolutely every idea a person could think of into a song and see what worked. Here, we go from Kelly Clarkson verses to a roller-coaster chorus to a dubstep breakdown that dates the song as surely as radiocarbon — then back again. It shouldn’t hang together, but the adventurous vocals and vivid lyrics keep the track from going off the rails.