Photo: Murray Close/Murray Close

Alex Garland’s Civil War, about reporters covering a conflict in the United States at some unspecified future date, might be the most controversial movie of the year. From the moment the film’s first teaser dropped, Garland, an English writer turned director, was criticized as politically clueless for envisioning a scenario in which a rogue president would be targeted by a coalition of Texas and California (which have nothing in common when they vote in national elections), and also for releasing a film on that subject in the first place during an election year with the same presidential candidates as 2020, one of whom tried to nullify the other’s victory. The discord surrounding the movie increased after its premiere at the South by Southwest Film Festival, where Garland said in interviews that Civil War avoided political specifics on purpose in order to start “a conversation” while refusing to speculate on details the movie didn’t include; instead, he said that it was mainly a love letter to journalists, war reporters in particular. There were also gripes that the film was more violent, slick, and loud than substantive, and perhaps represented an “Emperor’s New Clothes” moment for the director of Ex Machina, Annihilation, and Men, all of which were hotly discussed by genre fans but have yet to form a critical consensus.

Garland spoke to Vulture for an hour in Los Angeles recently, elaborating on his decision to avoid political specifics and what responsibility he has to the 2024 American electorate, and digging into more nebulous questions about the relationships between screenwriting and directing, a movie and its audience, and artists and the eras in which they make art. Garland clarified his decision to step away from — though not, as has been previously reported, entirely quit — directing, saying that it was not driven by criticism of him or his latest film, but in fact dated back to the filming of Civil War two years ago.

How are you feeling right now? Or is that a trick question?

It’s a fair question. It’s weird. Selling movies, which is basically what I’m doing, is not normal human interaction. It just isn’t. It’s always a little bit odd. This movie is particularly odd, so it amplifies the weirdness. I can normally relax slightly more when I’m doing interviews, and I’m more guarded, more careful, choosing words more precisely — or attempting to.

I do need to ask you —

You can ask whatever you want.

Why would you want to stop directing?

It’s a complicated thing. What I said was “for the foreseeable future,” and I mean that in a literal sense. I’m working on four — in a way, five — film projects at the moment, none of which are for me to direct. They’re for other people. So I’m working hard, and I consider screenwriting to be a form of filmmaking. Prior to directing, I functioned as a screenwriter, and I don’t think it’s lesser. I just think it’s other. It has different obligations.

You have a family, yes?

Yeah, two kids. I shot a bunch of stuff really back-to-back. I was away a lot, away from home a lot, away from life a lot. That is a contributing factor to the decision. But also I think temperamentally I’m a writer who opted to direct, rather than someone who always had a burning desire to direct. The first film I directed, Ex Machina, I did to protect certain scenes, to not leave them open to discussion.

Alicia Vikander and Domhnall Gleeson in Ex Machina.

Photo: Universal Pictures

Protect them from whom?

From whoever the director might be. I just wanted to remove that voice for a period of time. And that would have been true with this movie as well. Like, there would be certain scenes in the way they’re unfolding that I would have found impossible to watch if they weren’t unfolding in the right way.

Which scenes in Ex Machina were you concerned about being mishandled or misinterpreted if someone else had directed the movie?

It would have had to do with the specificity of some of the dialogue. On the day, in the moment, there might be an actor who suddenly doesn’t feel like a line is fitting in their mouth, and they say, “Hey, can I say it like this?” And the director, who may not understand the exact reason a particular construction of sentences is in there, might say “sure” and then it’s gone and something is lost. There would be many moments in Ex Machina to do with a specific way something is being described.

Did your concerns have to do with the story’s sexual aspects?

Absolutely, yeah. It’s a thought experiment I often have: I’ll think of a script and I’ll imagine, What if X directed it? What if Y directed it? What would happen? And in Ex Machina, there was just some stuff that was close to a line and that could not go over a line. It isn’t always the case, but I’ve had a few experiences where stuff in a screenplay was getting changed in a way I couldn’t stomach. Sometimes I would then turn into a kind of pit bull, which I don’t like doing and I don’t want to be. And sometimes I would just have to shrug.

Was it a case where you felt the intent or the quality of the writing had been compromised or mangled? Or was it simply “That’s not how I would have done it”?

On occasion, it might be “That’s not how I would have done it.” But often it wasn’t to do with — this is going to sound like a contradiction with what I just said — the exact words; it would be to do with the exact meaning behind the words. You could actually change the dialogue and hold on to the meaning. That would be completely unproblematic. I’ve never cared about that. But the meaning of a scene can completely change, and the role of a scene within a story can completely change.

Can you give me an example?

I’d rather not.

Maybe later?

Privately, I could do them easily! I could reel them off! But then also you get confronted with another weird thing, right, which is: So the film is not as you intended, but who cares? Does it actually matter? Film is collegial.

In theory!

In theory. I think the way I work is pretty collegial! But what will happen is, there will be some things I care about massively, and it has to be that way on that thing. But in and around that thing, there’s enormous latitude to change things, and I’m actually looking for other people to elevate it past the point that I would have been able to consider.

So these four or five new projects you have in the works are all things where you’d be okay with saying, in effect, “Fly little bird, leave the nest, whatever happens is okay”?

Correct. It’s to do with … to me, it feels like my last four films as a director are a sequence of films which are following a sequence of thoughts. Civil War, I think, as far as I can tell, ends that sequence.

What is the sequence? Is it “the science-fiction sequence”? “The speculative-fiction sequence”?

I probably lean towards science fiction. Fiction is almost by definition speculative —but speculative to degrees, and sci-fi is definitely at the far end of one of those degrees. I also think sci-fi sort of allows for or even encourages big ideas, which is nice. You don’t have to feel embarrassed of them, actually. Sci-fi audiences kind of dig them.

But no, to answer your question, it has more to do with a set of thoughts I had about how to present arguments within a film as conversation. I’m not saying I’m always successful at that, only that it’s a private set of thoughts that I’m following through on.

By “arguments,” do you mean not making a case for or against a thing but rather a dialectical exchange of ideas?

Exactly, and a kind of inclusive one. Bear in mind, I’m not saying I always manage to do that. One of the things I have to do is be careful about what I say because that would disrupt the conversation between the film and the audience, you know? I recently watched All That Jazz, which I hadn’t seen for a really, really long time. And while I was watching, I was having what I felt was an intensely personal conversation, I guess, with many people but also with Bob Fosse’s psyche. Would that conversation be helped by Bob Fosse giving me a memo in addition to the film he made? I don’t think it would have helped. I think the film would have been diminished, you know?

I wondered if the reception to Civil War at South by Southwest, as well as the negative or critical reaction to some of your comments in interviews, played into your announcement that you didn’t want to direct anymore.

No, no, no, no. The decision predated that. In fact, it located itself in my mind in a clear way while I was shooting Civil War. That’s when I started stating it sometimes to people I work with, just to give them a heads-up: “Hey, I’m gonna be taking some time out for a while, right after this.”

Time out to write?

Well, no. It’s slightly more complicated than that because I’m about to do a film with one of the crew from Civil War, a guy called Ray Mendoza, who was our military adviser. In postproduction on Civil War, Ray and I started discussing a film, and I said, “You should direct this because a portion of what directors do is have answers to questions. It’s not the only thing a director does, but it’s a very important part of what a director does.” And in the case of this particular story, the person who has the answers to those questions is Ray, not me. As soon as Ray takes the position of a director, a particular authority is conferred that is then useful for the execution of what he’s talking about. But I also knew there would be some areas that it wouldn’t be fair to expect Ray to have to answer, like, “Why is the camera moving? Should this be a close-up? Should it be a developing shot? Now should we pop out to a wide shot?” So I said, “Let’s share this responsibility.” It’s not directing in the terms I myself would think of as directing.

So a Ray question would be something like “What’s the military objective in this scene, and why are they using this particular type of formation?”

Oh, it’s more than that. That would be a Ray question, but it would go well beyond that. This is, in a very profound way, Ray’s story.

What can you tell me about the film?

The film is an account of a real event. That’s basically what it is.

An event for which Ray Mendoza was present?

Absolutely. Notionally, in a credited way, it’s a co-written script. But really, on my part, it’s an act of transcription and organization rather than what I would normally think of as screenwriting. That will also be true with the directing. Actually, in a way, the writing of the script is an echo of the way I suspect the film will get made.

Let’s return to Civil War for a second. What year is the movie set in, more or less? It’s not, like, five years from now, is it?

In my mind, there were some things I was very specific about as a background sequence of events.

I ask because Jesse and Lee have a conversation where Jesse is talking —

—about a massacre, and there hasn’t been a massacre in the movie.

Right. She says Lee took famous photos of something called “the antifa massacre.” We don’t know if it was a massacre by antifa or of, but it seems clear that it happened a long time ago, when Jesse was a child or even before her birth. That would mean this story has to be set at least 20 or 25 years from now, right?

Yeah. But as for the vehicles, the phones, the sort of textural stuff of real life — a vehicle which is seven years old now is probably not going to be around 25 years from now, right? And there are a lot of vehicles in the film. In that respect, you couldn’t date this story. What you could do is apply a logical sequence of events that are alluded to within the film, which, to my mind, would allow for the situation we see depicted. But you can’t say, “Starting in 2024, here’s what happens: A, B, C, D.” The way in which some people can create huge graphs for a fantasy epic with multiple parts and figure out the laws and the timelines would be a wasted exercise on this movie!

Cailee Spaeny and Kirsten Dunst in Civil War.

Photo: A24

All that being said, I don’t know that anything depicted in Civil War is inherently more far-fetched than the 2019 Los Angeles of Blade Runner or Anthony Burgess’s future England in A Clockwork Orange, which, according to the author’s notes for an early draft, was set in 1980.

No, it’s certainly not inherently more far-fetched than either of those stories.

It’s interesting: Blade Runner is drifting towards something that is more closely related to our reality because of changes in artificial intelligence. And Clockwork Orange was always closer to reality because it was talking about the haves and have-nots, the Establishment’s fear of violent delinquency, what measures might be taken, whether those measures would work, whether they’d be reactionary or whatever. And that argument, I think, probably belongs to that period. It clearly scared the hell out of Stanley Kubrick at the point when he released the film and thought, Hang on, this is folding into reality quicker and more seriously than I thought possible.

When I rewatched A Clockwork Orange recently I was startled by how much of the grammar of that film has inserted itself into film grammar generally. Kubrick was a freakishly influential filmmaker.

The equivalent of one of those novelists or playwrights who is actually adding words to the language.

Is A Clockwork Orange the first film where you have a group of young men walking towards the camera in slow motion and then, within the slow motion, a moment of violence floating out? I’m just curious.

One thing we can say for sure is it’s the scene that made a lot of other directors go, “That was cool — I want to do that in my movie.” And they did do it. Scorsese, especially. Let’s go back to Civil War again, though!

No, no, I wanna stick with A Clockwork Orange because when I was talking about Civil War being an extension of a sequence of films and something I’ve been working through, bringing in A Clockwork Orange speaks directly to the thing — which is that there’s a disconnect between the intention of a filmmaker and the way a narrative is received. Not only is there a disconnect; it’s a good thing that there’s a disconnect because it involves the imaginative life and it’s built into the terms of conversation. Everything I say to you and you say to me, just in our talking, may not be fully understood either way. Conversation is in some respects impressionistic. It’s connected but impressionistic. And film is a really good exercise in demonstrating that. Clockwork Orange, for example, should mean either slightly or very different things to different people, and that is in no way problematic.

Speaking of problematic: There were complaints after the trailers and after the South by Southwest premiere that it was unrealistic to think California and Texas could be allied against the president because California votes Democratic in national elections and Texas votes Republican. I explained it to myself as, well, there are large numbers of Republicans in California who hate the rest of the state and want to secede; maybe they’ve seceded or taken over by that point in history, and that’s why California is allied with Texas. But maybe I’m wrong?

One of the reasons the film does not specify the reasons behind Texas and California is to consciously, deliberately leave that space as a source of engagement.

So my speculative interpretation —

Is as valid as mine.

And it’s not necessarily wrong?

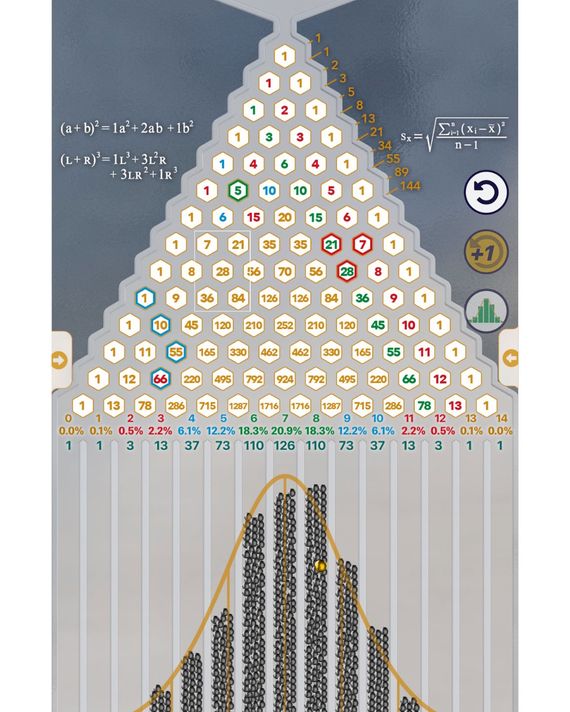

It is explicitly not necessarily wrong. What I would say is that all the thoughts put together, I hope — whatever disagreements you and I might have — a consensus would arrive from those things. Which, because I’m a fucking science nerd, I’m going to demonstrate to you now. [Garland takes out his phone and calls up the screenshot below.]

Photo: Galton Board App

Okay, what are we looking at here?

What we’re looking at is a Galton Board. It’s a series of ball bearings falling and it’s a random 50-50 on which sides of each of these shapes they bounce. But a consensus appears as a product of the accumulated states. That orange line shows the state of the consensus.

So if you applied this to an audience’s reaction to a film, could this Galton Board perhaps represent the fullness of time rendering a consensus verdict?

This is how I’m feeling watching All That Jazz. Bob Fosse might be there [points to the left side of the board], I might be there [points to the right side of the board], but this is the shape [points to the peak in the middle].

What do you make of the obsession with “solving” ambiguous endings and filling in every last bit of imaginative negative space in a story with explanations, backstory, and lore? Seems anti-art to me.

I totally agree, but it’s worth pointing out that even if you do attempt to fill every single gap in a narrative, you will still not get this perfect, harmonious, unified response to every single moment and every single beat. It just never appears! The quest is quixotic, you know? I think most mainstream movies do exactly what you said, and they are open to less interpretation than the other kind. But I suspect if you go on any film website, you’ll see fans angrily arguing over the meaning in a movie that already explains everything.

Refusing to explain everything is not a flaw. But it sure does make people mad!

The most satisfying film I saw last year was Anatomy of a Fall. It really does not answer one of its own central questions, and that in no way bothered me. In fact, I liked it even more for not answering it. But then there’ll be other people who walk out and throw their hands up in disgust going, “What the fuck? Did she do it or not?”

That’s funny because there are people who will insist that the film does in fact give you an answer, just as there are people who insist Zodiac gives you a clear idea of who the Zodiac killer was.

That would be another subjective response. Here’s another thing that’s interesting: I just don’t really care what the filmmakers say, personally. But what if the filmmakers say, “No, no, we gave an answer — it’s there, it’s this,” but I didn’t see it? Does that mean I saw the film incorrectly? I don’t think so.

I don’t know. But I do know that sometimes my misreadings of a film are as interesting to me as what the film is actually saying, because of what it reveals to me about myself.

Exactly. My whole journey over this sequence of films was a playing out of exactly what you just said. I felt with Civil War, this is as good as I will ever be able to do.

Are you comfortable saying what the film is about in a very general way?

What I can say is that Civil War is about a state. I don’t mean a state like a country; I mean a state of thinking, which is divided and contains a path to forms of extremism so there is something of the real world located within it.

Every science-fiction film is about the time in which it was made.

For sure. That’s one of the reasons I love sci-fi.

Therefore, Civil War is about our time too?

Yeah, I hope so — and I hope so in a kind of thoughtful and conversational manner.

What would you say to somebody who accuses you of being irresponsible for making a film like Civil War and releasing it during an election year?

The truest thing I’d say about that is I honestly don’t know whether it’s responsible or irresponsible because I would need to know too many things I don’t know in order to be able to answer that question. But what I do think is that there’s a converse, a counter to that, which is “What’s the consequence of not saying things? What’s the consequence of silence? Of silencing oneself or silencing other people?”

What is the film warning us about?

Two things. If I was going to be reductive in a way, and I’m not inclined to be reductive, I would say that — paradoxically, considering the subject matter — the film is about journalism. It’s about the importance of journalism.It’s about reporting. The film attempts to function like old-fashioned reporters. That’s thing No. 1.

What’s the other thing?

Just a simple acknowledgment that this country, my country, many European countries, countries in the Middle East, Asia, South America, all have populist, polarized politics which are causing and magnifying extreme divisions, and the end state of populism is extremism and then fascism.

That relates back again to journalists because you have governments with checks and balances, but you need this other thing, which is the press — free, fair, but also trusted. And at the moment, the dominant voices in the press are not trusted. They’re trusted to a degree by the choir they’re preaching to but not by the other choirs. I’m in my 50s. When I was a kid, if in what the old days was called a “broadsheet newspaper” ran a story about a corrupt or lying politician, it didn’t matter whether you were a reader of that newspaper or not, the impact would be enormous and very likely would end that person’s career. That world has gone.

It’s funny because so many movies still end with a video or audio recording being played publicly to prove that someone is corrupt, and the implication is that the bad person was fired or sent to prison.

It worked perfectly in a 1970s paranoid conspiracy thriller because the heroes got the story out, and the sinister government course or the sinister corporate course was screwed by the story having come out.

Why is that kind of ending hard to accept now?

It’s a consequence of three things. One is powerful external forces: politicians who deliberately undermine trust in the media for their own ends because it’s useful for them to have the media be distrusted. Social media creates an enormous amount of noise and counternarratives and theories that just create a kind of static over all of the information; it has a tonal quality which is often akin to shouting. And then also, very large, very powerful media organizations, which found themselves driven less ideologically than by advertising, needing to target audiences and hold on to those audiences. That became more important than unbiased news reporting.

It’s easier to get people to listen to your message if it’s one they already agree with?

Yes, and that works very well. But it doesn’t work well for everyone who sits outside of that audience.

How does this relate back to the mentality of the journalists you depict in Civil War?

They’re reporters. They’re reporters. The era I grew up in was an era of reporters in news journalism.

It doesn’t seem to matter to the reporters in Civil War if they’re embedded with the good guys or the bad guys.

Why would it? They’re reporters. I think we need those kinds of people because we need for journalists to be trusted because they are the people that hold governments to account. And governments will, at times, regularly, predictably become corrupt.

What was the influence of your father, who was an editorial cartoonist, not just on this movie but on who you are?

Huge. In two really significant ways. Every night Dad would watch the nine o’clock news because he’d be looking for a story that he’d do a cartoon about the next day. All of — not all, but the vast majority of — his close friends were journalists. My godfather was a foreign correspondent; my brother’s godfather was a different foreign correspondent. They were around the kitchen table; they were sometimes living in the house. I grew up listening to them. Like the journalists in this movie, they could be spiky, they could be difficult, they could be compromised or conflicted, but there was a kind of purity in this one aspect of their work that they were deadly serious about.

The other thing is Dad was a cartoonist, so I grew up around drawing, and I grew up around comic books. Comic books are sequences of images, and that’s, basically, even as a screenwriter, I am offering up sequences of images and editorial decisions. The scene ends here, and this image contrasts with the thing you just saw, and that carries its own implicit meaning or complication.

It’s so interesting hearing you talk about your father’s influence and journalism because, now that I think about it, your films feel reported. Like you’re going, “Here are the characters, here are the issues they have conflicts over, here is the story, here is the ending. Whatever you make of all this is up to you because I’m on to the next thing.”

That’s exactly it. And I am aware that the attitude pisses some people off because they want the reassurance of knowing where the filmmaker stands with regard to various issues.

I remember when Ex Machina came out, I had arguments with people about the ending, where Ava leaves Caleb trapped. Some people wanted her to take him along or at least free him. How do you feel about that?

Her point of empathy was the robot played by Sonoya Mizuno. Those two empathize with each other. They were in the same boat. She was in a prison; she was trying to get out. Kyoto, Sonoya’s character, empathizes with Ava. That would be my answer. But I find it interesting that people said it was cruel or non-empathetic, that it proves AIs don’t have empathy. I was like, “Empathy with who?”

It’s astonishing to me that Ex Machina came out ten years ago. You have a sequence where the creator, Nathan, takes Caleb into the laboratory and talks about how he used his power as a tech billionaire to basically eavesdrop on every communication in the world to create this AI. That’s what’s in the news now, that very thing: the scraping of information without consent or compensation to create an agglomeration that machines plug into.

I always felt a real skepticism with these tech leaders. Because they work in tech, we make an assumption that they’re geniuses, and they’re very quick to also make that assumption about themselves. And I sort of think, Eh, you’re entrepreneurs. It just so happens that you’re not in milk production; you’re making social media or whatever the hell it is. That doesn’t confer on you any special status at all. And as the years roll by, that’s the other thing that’s been demonstrated — they’re really not geniuses. They’re just people with a lot of money and a lot of power. That in itself doesn’t make a genius.

Was Ex Machina a warning?

I definitely thought about it in those terms. It was actually in the TV show Devs that I really went further down that line. In fact, one of the characters in Devs, one of the computer programmers, says he’s not a genius, he’s an entrepreneur.

Do you ever read the news and think, Yeah, I called it?

I never think my stuff is prescient. I know there’s a big conversation happening about these issues at exactly the same time that I write things, so I know it’s not prescient; it’s more sort of factual. I think people are very, very good at correctly anticipating problems. They’re just terrible at doing something about it. They just don’t act.

I organized two screenings of Annihilation, and afterward, the audience had an astounding number of different interpretations of the film: that it was about the uncertainty principle, that it was about grief, that it was a metaphor for cancer. There were assorted theological readings. I wondered if you had a specific reason for making that movie.

If I was going to be very reductive about Annihilation, it would probably be about self-destruction, that that could include cancer or behavior or any number of things. But this is true of all the films I make: It’s not one goal, one thing; it’s a set of thoughts. Ex Machina is that too, explicitly. It’s just easier for me to talk about the things that are explicit, like machine sentience, rather than the things I hope will float out, such as gender — where gender resides, whether it’s conferred or taken, that kind of thing.

Another thing I noticed about your movies, as both writer and writer-director, is that they are filled with people choosing to place themselves in harm’s way, whether they’re Ava trying to escape the complex, or the journalists in Civil War, or the crew in Sunshine trying to plant a bomb that will reawaken the Sun.

That’s quite interesting. I’ll refrain from talking too much about that and getting a bit autobiographical, but I do sometimes think there’s a part of me that is thoughtful and there’s a part of me that is delinquent. And I can see the delinquency.

What do you mean? Delinquent in the “potential droog” sense, or in some other sense?

Holistic.

Holistically delinquent?

In some respects. You know, people have different sides to their personality and character. I can see it clearly in Civil War. It’s thoughtful and it’s conversational, and I think it would be fair to say it’s also highly aggressive. The two things are just right next to each other. In these films, there’s something very restrained and also something unrestrained.

That’s also true of 28 Days Later.

Danny Boyle and I like working on a long-term sequel to that. He’s in prep now, and it starts shooting pretty soon.

What a shitshow it must be in that world 28 years later!

Well, in some ways yes, but in some ways no. We had a kind of deal between us, which was to not be cynical, and I think both of us are sticking pretty hard to that principle.

You called yourself a science geek earlier, and you obviously enjoy getting philosophical, but you’re not much for explanations, are you?

I don’t have any explanations! The larger the searchlight, the larger the circumference of the unknown.

Titled Warfare, the film is rumored to be a dramatization of events that occurred during the Iraq War in 2006 and that earned Mendoza, a former Seal Team 6 member, a Silver Star “for conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity in action against the enemy.” The cast includes Noah Centineo, Taylor John Smith, Adain Bradley, Michael Gandolfini, Henrique Zaga, and Evan Holtzman.