When the curtain rises Saturday evening on Los Angeles Opera’s “Turandot,” composer Giacomo Puccini’s last work will feature the L.A. debut of the production’s biggest star: monumental stage sets designed in the early 1990s by David Hockney, the renowned British painter and celebrated chronicler of Southern California life.

Bathed in deeply saturated red and ultramarine, the swooping curves and dagger-like angles of Hockney’s “Turandot” sets are the backdrop for the grim fairy tale about a cold-blooded Chinese princess who has her would-be suitors beheaded — until one of them melts her heart.

Hockney’s scenic design, reminiscent of stark German Expressionist filmmaking with a dash of the backgrounds in Walt Disney’s “Fantasia,” is a virtuosic testament to the artist’s lifelong exploration of abstract figurative painting and his abiding love of opera.

“We’ve been trying to program Hockney’s ‘Turandot’ for 30 years,” said Rupert Hemmings, vice president of artistic planning for L.A. Opera, which commissioned Hockney sets for the operas “Tristan and Isolde” and “Die Frau Ohne Schatten.” “The task is always to create something that audiences come for. It could be the soprano or the director. Here, it’s Hockney, who created a visionary work of art that the opera happens within.”

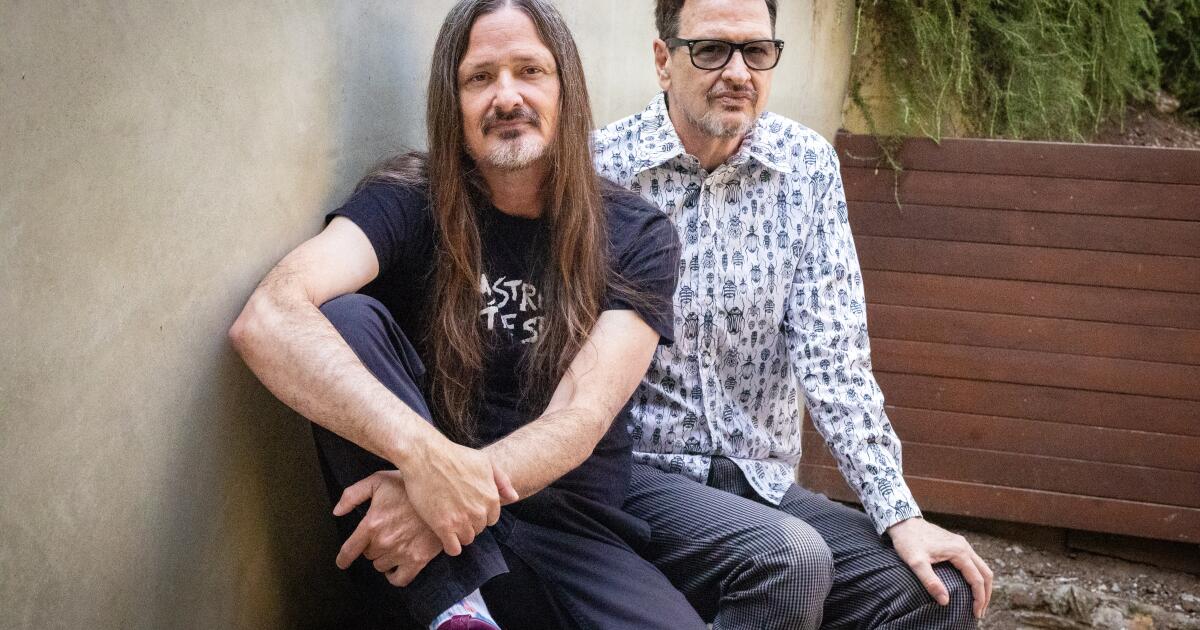

The cast of “Turandot” runs through final rehearsals Monday of the David Hockney production of “Turandot” at the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion.

(Jason Armond / Los Angeles Times)

Among the grandest of grand operas, “Turandot” is a demanding enterprise.

“There are 342 people in the cast and crew, 95% of whom are union,” Hemmings said. “To work with an 86-piece orchestra and to cast, clothe, rehearse, corral and pay 128 performers is expensive, and to protect their voices, we can only play twice a week.” With a seating capacity of 3,100 for each of six performances at the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion, he added, “it won’t even be break-even.”

In addition to the cost of personnel, L.A. Opera has spent $80,000 to rent the production assets — the props, Hockney’s sets and costumes by Ian Falconer, the writer and illustrator of the popular “Olivia” series of children’s books — from the San Francisco Opera and the Lyric Opera of Chicago, which commissioned the “Turandot” designs 34 years ago.

Having created opera sets since 1975, including 18 months of work on L.A. Opera’s “Tristan and Isolde” in 1987, Hockney took on the “Turandot” commission with fierce opinions. In his 1993 autobiography, “That’s the Way I See It,” he wrote, “I had seen many productions of ’Turandot,’ most of them kitsch beyond belief, overdone Chinoiserie, and too many dragons. … For the first scene, the city of Peking, I suggested that we take the dragons away and put them into the roofs, in forms that felt like dragons.” The result is a strikingly fantastical depiction of the city now known as Beijing, using, Hockney added, “harsh edges, strong diagonals, mad perspectives.”

According to Drew Landmesser, former deputy general director of the Lyric Opera of Chicago, Hockney — who moved to Los Angeles in 1964 — transformed a tennis court on his Hollywood Hills property into a work studio. Unlike other designers, who typically create set models at a scale of a quarter-inch or half-inch per foot, Hockney built a “ginormous platform with models so large that he could crawl around them to explore the space and how people would move in it.”

Workers move giant “Turandot” set pieces backstage for the second act during a rehearsal.

(Jason Armond / Los Angeles Times)

The artist also installed his own lighting system to ensure accurate representation of the intense colors he chose for his set pieces, which include red exterior facades that soar to 30 feet and a scrim accented with jade green and royal blue painted on seamless canvas that stretches 60 feet across the stage.

After two years of development, translating measurements for construction of the “Turandot” sets took six weeks of computer work. The sets, props and costumes cost around $1 million to produce, said Landmesser, a “not disproportionately large investment” shared by the Chicago and San Francisco companies and amortized through rentals. (That production figure does not include fees paid to the creative team, including Hockney, costume designer Falconer and the lighting and stage directors.) Since 1992, the sets have been used more than a dozen times across the U.S. and in Naples, Italy.

During a visit to rehearsals last week — as lead tenor and artist-in-residence Russell Thomas repeatedly banged an enormous gong, signifying the end of Act 1 — Hemmings and L.A. Opera technical director Jeff Kleeman described the labor-intensive process of mounting the show.

“The level of detail to produce and resource it properly takes months and months of analysis,” said Kleeman, who pores over renderings made with computer-aided design software to adapt Hockney’s design for the L.A. Opera stage and establish placement of scenic elements and lighting in what is known as a composite ground plan.

“Act by act, piece by piece, we make it fit,” he said.

The sets, which San Francisco Opera pays to store in a warehouse in Modesto, were broken down into “thousands of pieces and fit together like Tetris to reduce damage and fit into three 53-foot trailer trucks with eight-foot ceilings,” Kleeman said. Upon the sets’ arrival in L.A., his 64-strong stage crew spent five 10-hour days in three teams, sorting the pieces for each act of the opera, assembling them, making necessary repairs and positioning some 800 lights.

‘Turandot’: What to know

Three quick points about Puccini’s last opera

“The sets are what we call soft walls,” Kleeman noted, “made from wood with fabric coverings. These days, sets are constructed with steel and plywood, which are heavier and more durable. Soft walls weigh less and are cheaper to build, but after a couple of uses and trips in the truck, they tend to get worn.” Enter the scenic painters, who custom-blend and color-match Hockney’s highly saturated hues to touch up the sets and create a board lined with pieces of painted tape for quick patches before or during a performance.

Intermissions in the show last 20 to 25 minutes, to allow the 43 members of the wardrobe, wig and makeup crew to prepare performers for the next act and the stage crew to roll pre-built sets into position. About one-third of the scenery is “gripped,” Kleeman said, meaning pieces are carried onstage and assembled by carpenters. “It sounds chaotic,” he added with a smile. “Everything needs to be placed exactly where it should be, in a highly choreographed way, and with each rehearsal we refine the approach. So as big as it all seems, it becomes a routine.”

Workers move pieces of a roof during a set change.

(Jason Armond / Los Angeles Times)

Technical director Jeff Kleeman during rehearsal in the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion.

(Jason Armond/Los Angeles Times)

The towering sets are more than just spectacle, senior design manager Carolina Angulo said. “The use of forced perspective and oversize proportions unconsciously leads the audience to think about the characters’ place in this world and to feel their emotions.”

In presenting the San Francisco Opera Medal to Hockney in 2017, General Director Matthew Shilvock cited the artist for his impact on the art form.

“His productions are bold expressions of archetypal emotions, deeply rooted in a strong sense of spatial resonance and scale,” Shilvock said. “He finds rhythm in color and design and creates portals that we enter with thrilling excitement.”

Hemmings concurred, calling Hockney’s “Turandot” a provocative conceptual design that remains timeless.

“A lot of opera sets last for more than 30 years,” he noted. “If this ‘Turandot’ got to the point of it being worn out, someone would rebuild it. You would never get rid of it. That would be like throwing a David Hockney painting away.”

A “Turandot” set piece has hand-written notations about which act it’s for.

(Jason Armond / Los Angeles Times)

‘Turandot’

When: 7:30 p.m. Saturday , 2 p.m. May 26, 7:30 p.m. May 30, 2 p.m. June 2, 7:30 p.m. June 5 and 8

Where: Dorothy Chandler Pavilion 135 N. Grand Ave., L.A.

Tickets: $34 and up

Information: (213) 972-8001, LAOpera.org

Running time: 2 hours and 55 minutes (including two intermissions)