Steven Hackel thought it was a prank at first when the call came, early in the morning: “What do you mean the church is on fire?” He raced from his Pasadena home to the 249-year-old Mission San Gabriel, which was ensconced in flames devouring the historic structure.

Hackel was not a member of the still active parish; but as a UC Riverside history professor specializing in California’s missions, he was intimately familiar with the small, on-site Mission San Gabriel Museum, which he’d been helping to steer, in various unpaid capacities, for almost a decade.

As 80 firefighters from seven cities battled the four-alarm fire, Hackel and about half a dozen others set out to rescue the museum’s collection, which the fire hadn’t yet reached. They carried out about 100 objects — Native baskets, 17th and 18th century paintings, rare books and photographs — from the museum building, which was intact but for smoke and water damage. They stored the items at the convent next door before relocating them to proper art storage weeks later.

Firefighters at the San Gabriel Mission on July 11, 2020. The fire destroyed the roof of the church and much of its interior.

(Andrew Campa / Los Angeles Times)

That terrifying experience was compounded by the timing: the fire happened on July 11, 2020.

“It was COVID,” Hackel says. “We’d spent three months avoiding all public contact with people and here we are. The museum was very, very tightly packed. So we were freaked out. Everybody was really scared.”

But they felt compelled, nonetheless, to push forward and try to save the collection.

The Mission San Gabriel Museum — a new version of which opens to the public on July 1 along with the mission itself and its renovated church — may be small and little-known. But it’s critically important, Hackel says. L.A.’s Southwest Museum of the American Indian, which was inaugurated in 1907, may be slightly older; the Autry Museum of the American West may be larger, with collections totaling more than 600,000 objects and cultural materials. But the Mission San Gabriel Museum offers curated historical objects within a relevant setting, providing unique context. The mission was established in 1771, the fourth of California’s 21 Spanish missions, and the on-site museum has been in continuous operation since 1908. (Originally located in Whittier Narrows, the Mission San Gabriel was moved to its current location in 1774.)

“This is a place of memory,” Hackel says. “This is where the missionaries lived, and where Native people from distant regions — more than 7,000 of them — came and had their struggles. It’s where the human drama played out — here, on this site. And the museum helps us understand this complicated Native American and Catholic story.”

Grapes grow on a trellis in the mission courtyard near the newly refurbished museum.

(Brian van der Brug / Los Angeles Times)

The Mission San Gabriel Museum has been shuttered for three years. But the fire proved an opportunity: with the galleries emptied out, Hackel says, the museum could rebuild from the ground up — both physically and conceptually. The museum reimagined itself in order to present a more historically accurate and inclusive picture of the Catholic mission and the Indigenous communities it colonized. This inevitably involved a reckoning with the past. Because despite that the mission was built by indigenous people, with about 5,600 Native Americans buried there, the Native experience had not previously been represented in the museum.

Its inaugural exhibition — “Mission San Gabriel Arcángel, 1771-1900: Natives, Missionaries, and the Birth of Catholicism in Los Angeles” — is an attempt to publicly recognize “a 250-year-long erasure of the mission’s Native history and to displace a Eurocentric understanding of the legacies of Spanish colonization and Catholic missionization,” the museum said in its opening announcement.

Inside the newly refurbished Mission San Gabriel Museum.

(Brian van der Brug / Los Angeles Times)

The collection, too, has suffered challenges in the past. Objects hadn’t been properly cared for over more than a century, Hackel says. Exhibitions were presented on crowded walls with little curatorial order. There was no proper storage — instead, valuable items were stacked in the museum attic and a nearby basement. Paintings faded from decades of exposure to sunlight. Vellum-bound books dried up and weathered. Textiles deteriorated.

The neglect was due, in part, to lack of resources — the museum has no dedicated staff. There’s never been a professional director, permanent curator or conservator. There’s no endowment or dedicated communications team. There was a volunteer advisory council that met sporadically as of 2010, but it dissolved shortly before the pandemic. “It’s been run, lovingly, by volunteers,” Hackel says.

Just as problematic: there was no collection inventory or provenance documentation. It was a mystery as to where many of the museum objects had come from, as well as what, exactly, some of the items were in the first place. Confusion abounded. Paintings might have been done by a famous 18th century artist or by an unknown student. Some seemingly historic woven baskets that were on display in the museum turned out to be contemporary, probably manufactured within the last 20 years.

The collection had also been whittled down from the early 19th century, with objects stolen, lost or damaged and discarded including silver and gold-plated ornaments, mission records and liturgical texts. The original paintings collection had dwindled by half, Hackel estimates, based on the mission’s annual reports from the 1770s to the 1830s.

“That was always the concern, the loss of the heritage of the mission,” Hackel says. “The challenge with the collection was trying to figure out what was dated to pre-1830, the mission period, and what was given or purchased later. We didn’t want to spend money conserving something that wasn’t relevant to the history of the site.”

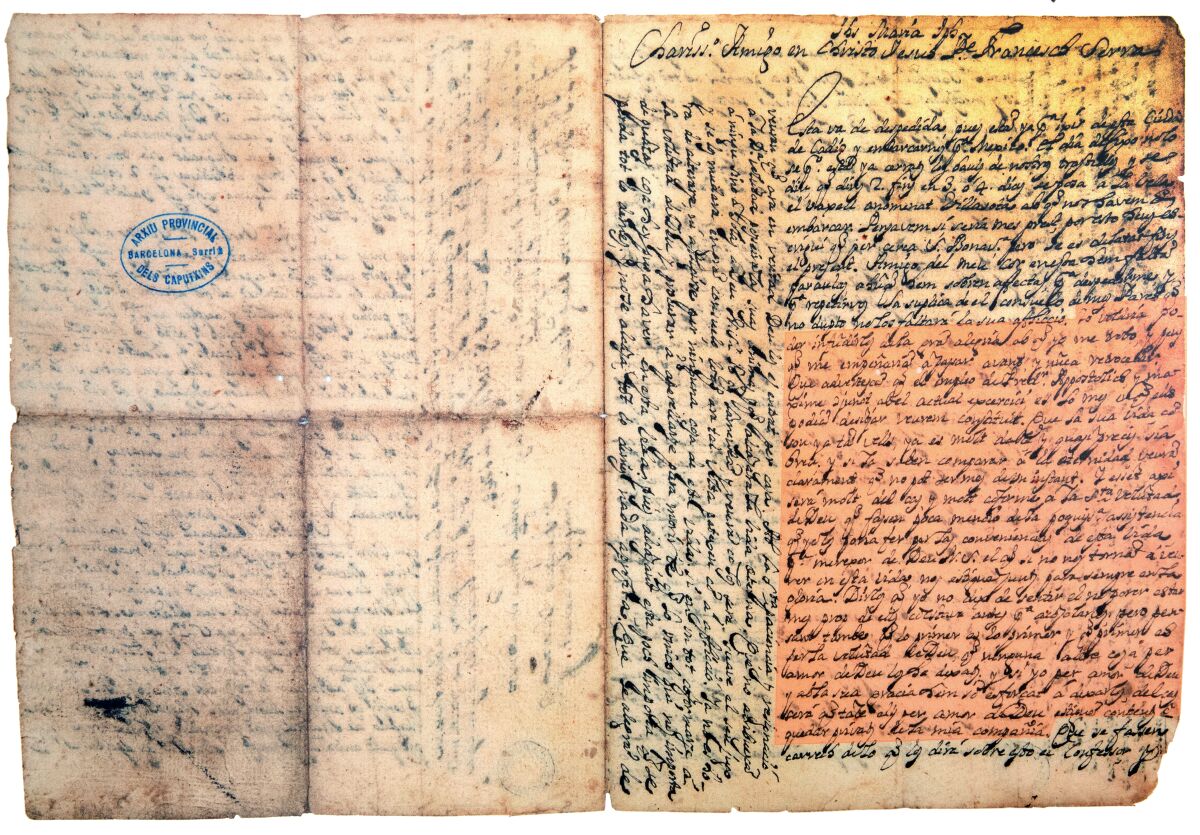

A reproduction of a letter written by Father Junípero Serra, in 1749, on display at the museum.

(Brian van der Brug / Los Angeles Times)

The museum had actually begun a rudimentary inventory project in 2017, in an Excel spreadsheet. With money from the archdiocese, it soon began consulting with conservators and book historians at San Marino’s Huntington Library, Art Museum and Botanical Gardens as well art historians from Mexico. “To figure out what was what,” Hackel says. But those efforts slowed at the onset of COVID-19. They picked up after the fire “because with everything out of the museum, we could study it,” Hackel says.

Then, in 2021, with a $30,000 grant from the California Bishops Council, the museum increased its inventory efforts. In 2022, Hackel procured a $25,000 National Trust for Historic Preservation grant and the Mission San Gabriel Museum further mined its history. It also began to rebuild the museum space itself, with upgraded displays, lighting and new technology. It couldn’t reconfigure walls, as the site is historic — the museum was once the padres’ quarters — but walls were patched and painted and floors refurbished. An improved HVAC system, blackout shades, a new alarm system and security cameras were added, along with UV-protected display cases. The museum increased exhibition space by 20%.

Cleaned and conserved Native American basketry from the collection in new display cases.

(Brian van der Brug / Los Angeles Times)

Most important, the Mission San Gabriel Museum confronted its historically ethnocentric perspective.

Hackel served as lead curator for the museum’s inaugural exhibition, post-fire. He worked with associate curator Yve Chavez, a member of the Gabrieleno Tongva San Gabriel Band of Mission Indians who’s also an assistant art history professor at the University of Oklahoma. She, in turn, consulted with members of her tribe, including Chief Red Blood Anthony Morales, “to make sure Native voices were heard, that our perspective was represented,” she says. “That each room of the museum touched on our ancestors’ experience or our culture.”

The Archdiocese of Los Angeles weighed in on nearly every aspect of the show as well. Non-Native experts provided information about California Indian basketry and Spanish colonial textiles. Hackel spoke to historians and curators and wrote new wall text and object labels. Items in the collection were cleaned and conserved. Thirty original artifacts are now on view along with 36 photographic reproductions of documents and art from other institutions. The show also includes digital infographics, a video and audio elements.

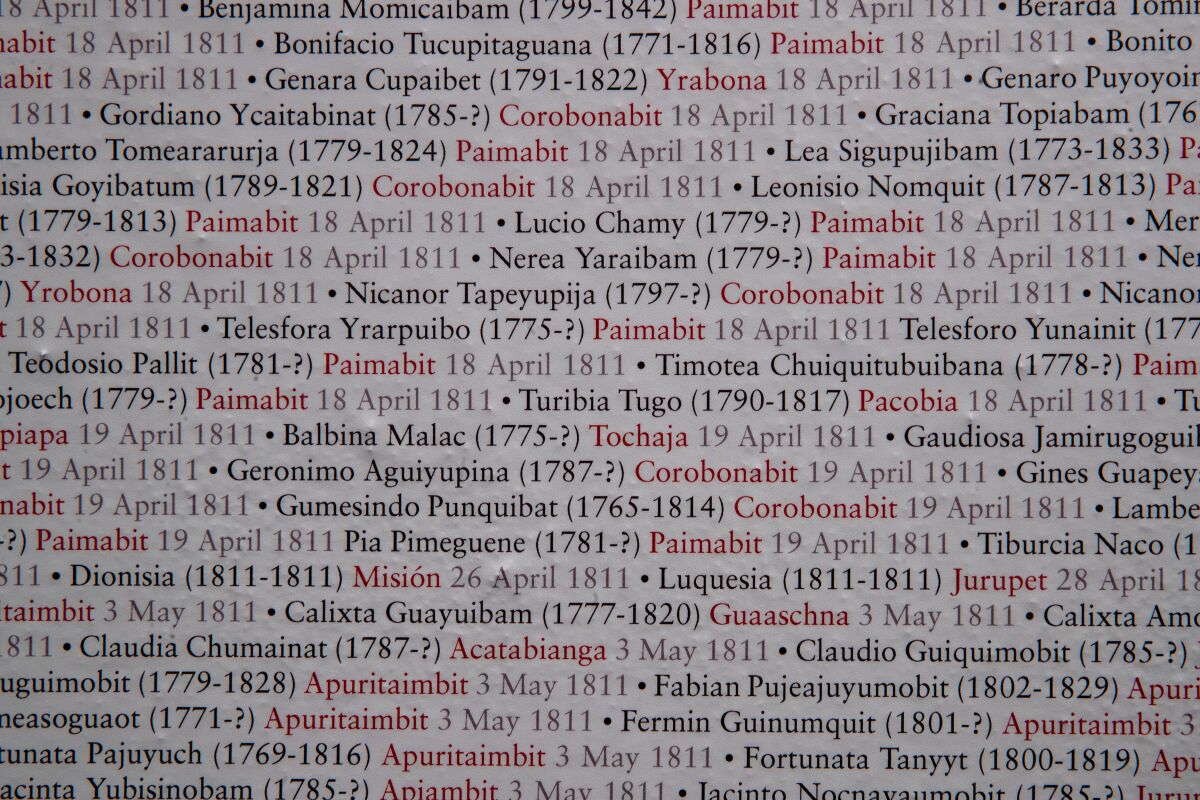

A detail of the commemorative wall of names.

(Brian van der Brug / Los Angeles Times)

Upon entering the first of seven galleries, visitors are greeted by a 16-foot-tall commemorative wall featuring the names of 7,054 Native Americans who were baptized at the mission between 1771 and 1848. The names came from the church’s baptism registers. Individuals’ village name, Native name and year of baptism are included, along with their birth and death year, if known.

There’s also a digital map that pictures the progressive displacement of Native people to the mission, starting in 1771, and the gradual disappearance of their villages. “Eventually, by 1840, these villages were gone,” Hackel says.

A digital map of Native Americans’ migration to the mission.

(Brian van der Brug / Los Angeles Times)

One gallery shows what life was like at the mission through paintings, legal documents and an 18th century agricultural yoke. It addresses conflicting historical narratives. Crowded conditions in the mission dorms, and the lack of understanding of germ theory at the time, led to “incredible mortality,” Hackel says. A reproduction of a handwritten letter by controversial saint Junípero Serra presents a far rosier picture of mission life. “But we know disease was a terrible problem, and we have that written into the show right here,” Hackel says, pointing to the adjacent wall text.

Among the Spanish colonial paintings on view is one by Juan Correa depicting Saint Ursula and another likely by José de Páez picturing a martyred saint. Another relic is an elaborately-beaded, silk chasuble from the mid-18th century, worn by priests during Mass, that was woven in China and then sent to Mexico City to be further adorned with silver and gold thread, sequins and glass beads.

A detail of a silk embroidered Chasuble on display at the museum.

(Brian van der Brug / Los Angeles Times)

Audio plays a key role in the exhibition. There are new recordings of mission era documents, such as a transcript of the 1785 trial of a Gabrieleno woman, known as Toypurina, who co-led a Native revolt at the mission. It was recorded with help from the Autry Museum’s Native Voices program. The USC Thornton Baroque Sinfonia, directed by Adam Knight Gilbert, recorded mission era music. Andrew Morales, Chief Morales’ son, voiced words from the earliest Gabrieleno vocabulary known in mission times, El Quilgui.

There’s also a short film on view, by Maya Santos, that features Chief Morales talking about his family history, Catholicism and Native American practices. It’s paired with a slideshow of photos of his community members.

The video and slideshow are critical to the show, Chavez says, because mission museums have historically neglected to represent contemporary Native American experiences.

“Now students and others who come to the mission see that Native people survived and are still practicing their culture,” Chavez says. “The missions were devastating to our communities. But despite all those years of violence and cultural oppression, we survived. Our ancestors persisted and made it possible for us to be alive today.”

Going forward, Hackel says, the museum hopes to secure funding to continue researching and protect the collection as well as upgrade storage. It also hopes to acquire new works and, eventually, borrow objects to display. “And to seek the return of objects that, at one point, were in this collection,” he says.

In the meantime, the exhibition is a unique collaboration between Native people, historians and the archdiocese.

“My hope,” Hackel says, “is that people will walk in and get a sense that you know what? There were Native people living here. There were 7,000 who came to this mission, and that they matter. And that we’re sharing aspects of their story.”

“Mission San Gabriel Arcángel, 1771-1900: Natives, Missionaries, and the Birth of Catholicism in Los Angeles”

Where: Mission San Gabriel Museum, 428 S. Mission Dr., San Gabriel

When: Tues. – Sun., 8a.m.-4p.m. through Dec. 15

Info: parish.sangabrielmissionchurch.org

Cost: Adult general admission: $15