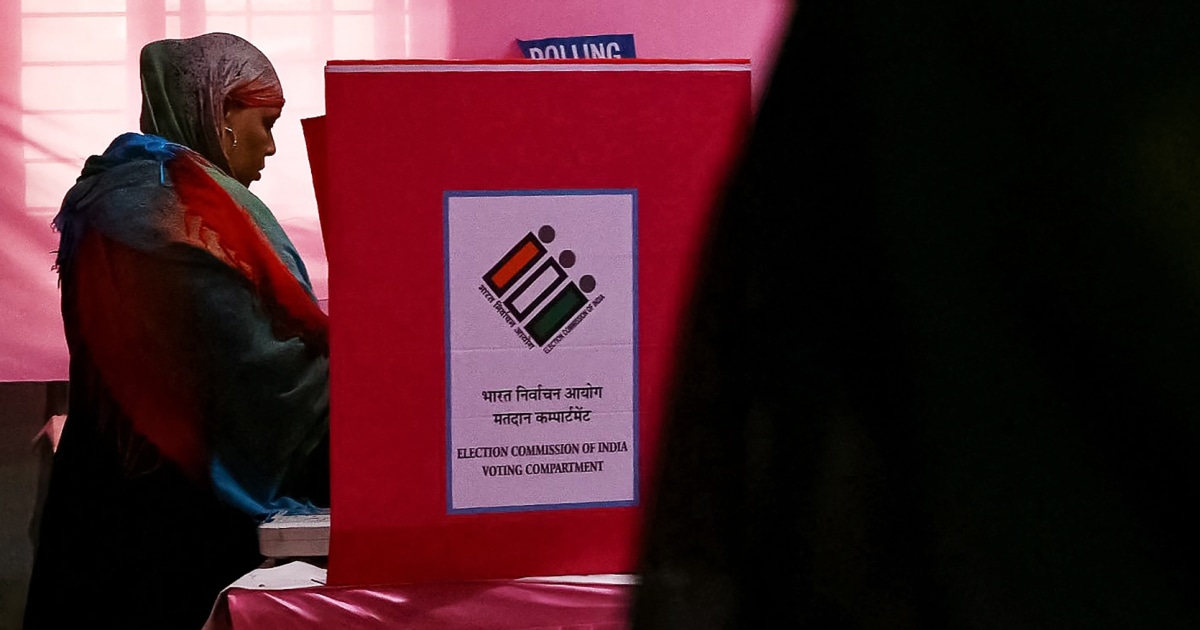

NEW DELHI — As India nears the end of the world’s largest election, extreme heat may be keeping voters from showing up at the polls.

Temperatures soared as high as 113 degrees Fahrenheit on Saturday in New Delhi as the capital and other parts of the country voted in the sixth phase of the seven-phase election, in which almost 970 million people are eligible to vote.

Voters were few and far between at one polling station set up at a Masonic lodge in the Janpath area of New Delhi, where more than a dozen police officers sipped chilled bottles of Coca-Cola as sweat streamed down their foreheads.

Mohammed Yusuf, 65, was already wiping sweat off his face as he walked up to the polling station about a quarter-mile from his home.

“It’s our responsibility,” he said after casting his vote.

“I have to cast my vote while I’m still alive,” he said. “Luckily I live close.”

The Election Commission of India said voter turnout in the Delhi capital region was a decade-low 57.67%, down from 60.5% in 2019. Turnout in other phases of the election has also been lower than usual.

It was unclear what was behind the lower turnout or whether it would help or hurt any candidates in the election, which runs from April 19 to June 1 with results announced on June 4. Prime Minister Narendra Modi and his Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party are expected to win a third consecutive term.

Like Yusuf, many voters arrived at their polling stations shortly after voting began at 7 a.m. to avoid the midday heat. But even then there was little respite from the oppressively hot and dry winds buffeting the city, with forecasters issuing a “severe heat wave warning” for the weekend.

India and other parts of South and Southeast Asia have been experiencing deadly heat waves this spring that international scientists say are being made more frequent and extreme by climate change.

Last week, at least nine people in the western Indian state of Rajasthan died from heat-related conditions as temperatures surpassed 120 degrees. Two others died of suspected heat stroke in the state of Gujarat, where Bollywood actor Shah Rukh Khan was reportedly hospitalized for the same reason.

In the Indian election, campaigns have adapted by concentrating their activities in the mornings and evenings and warning voters and volunteers to take precautions against the heat. In April, the Election Commission set up a task force to monitor heat wave conditions before each phase of voting.

Still, there have been multiple instances of candidates and election officials fainting at events.

Experts say that in addition to dampening voter turnout, extreme heat could also influence the way people vote, particularly in a country where more than half the population engages in agriculture.

“The things they care about change. They start to say, look, environmental issues are more important to me,” said Amrit Amirapu, a senior lecturer in economics at the University of Kent whose research found that voter turnout in rural areas increases when crops are devastated by high temperatures.

“They know that agricultural candidates will do something about it, specifically invest in irrigation which mitigates high temperatures,” he said.

In Delhi, there were more voters at a larger polling station at a high school less than a mile from the Masonic lodge. Some wore sunglasses, while others used umbrellas to shield themselves from the scorching sun that made the dust in the air shimmer.

Election officials had set up water dispensers all around the school, along with a first aid station. Dozens of pedestal fans and coolers stood in the domed gymnasium where voters lined up to cast their ballots.

“It’s extremely hot here,” said Ram Swaroop Verma, 78, as he sat on the steps of the gymnasium after casting his vote.

“It’s way hotter compared to last time,” he said.

Next to him, a man named Sashi pulled up a chair and sat down with a baby who fell asleep in the cool breeze from a fan.

“We get this right once every five years. It doesn’t matter if it’s too hot or cold, but I’m here to exercise my right,” said Sashi, 56, who goes by one name.

To encourage voter turnout, Delhi declared a public holiday on Saturday, rendering its usually bustling streets empty as most stayed within the cool of their homes.

Even the ice cream and coconut juice vendors that would normally be at every other corner were mostly taking the day off.

Yash Pal, a fruit juice vendor, was one of the few on the streets, but he had already run out of ice by 11 a.m. His assistant said it would take hours for more to arrive.

“It only lasts a few hours and becomes water very quickly,” Pal said.

Without ice, the only option on the menu was warm pineapple and lime juice. Pal offered it at a discount.