U.S. law enforcement and immigration officials have launched more than 100 investigations of crimes tied to suspected members of a violent Venezuelan gang, including sex trafficking in Louisiana and the point-blank shooting of two New York City police officers, according to two Department of Homeland Security officials.

The cases involving the Tren de Aragua gang show how hard it is for U.S. border agents to vet the criminal backgrounds of migrants from countries like Venezuela that won’t give the U.S. any help.

More than 330,000 Venezuelans crossed the U.S. border last year, according to Customs and Border Protection data, and Venezuela, like Cuba, China and a handful of other countries, doesn’t provide any criminal history information to U.S. officials.

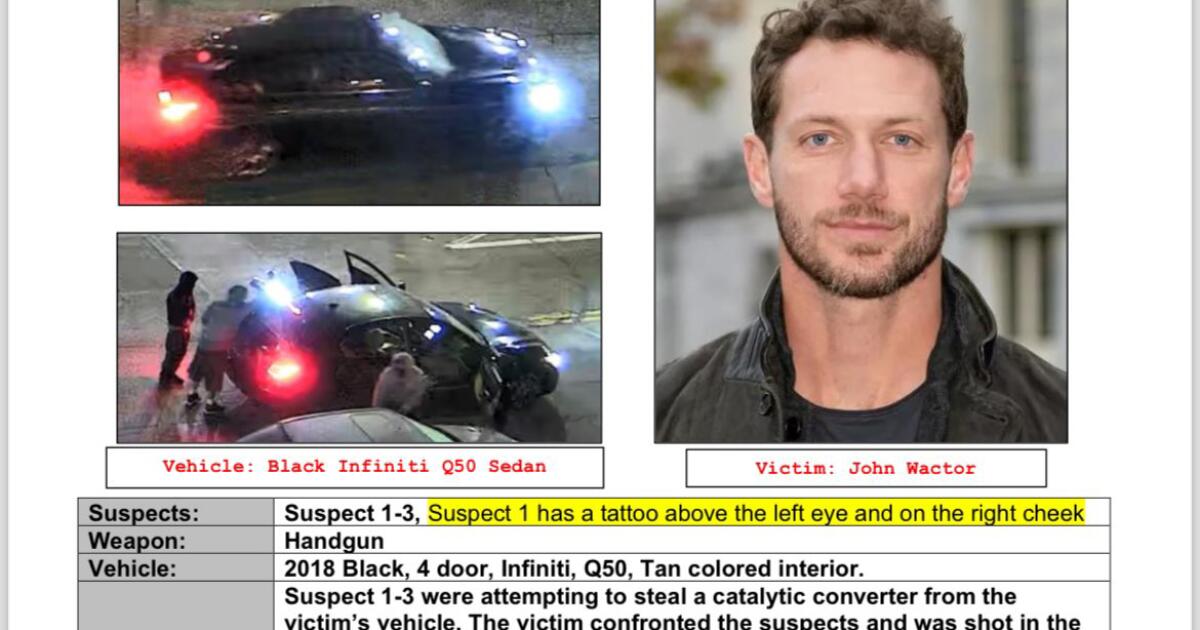

In the June 3 New York shooting, which both police officers survived, the alleged shooter had been encountered by the U.S. Border Patrol after having crossed into Texas illegally, according to New York police. He was then released into the U.S. to await an asylum hearing. It’s unclear whether his alleged affiliation with Tren de Aragua was known to Venezuelan authorities. Even if it was, that information wouldn’t have been available to the Border Patrol.

As former Border Patrol agent Ammon Blair told NBC News, unless agents get a Venezuelan migrant’s criminal history from Interpol or “they already have a criminal record inside the United States, we won’t know who they are.”

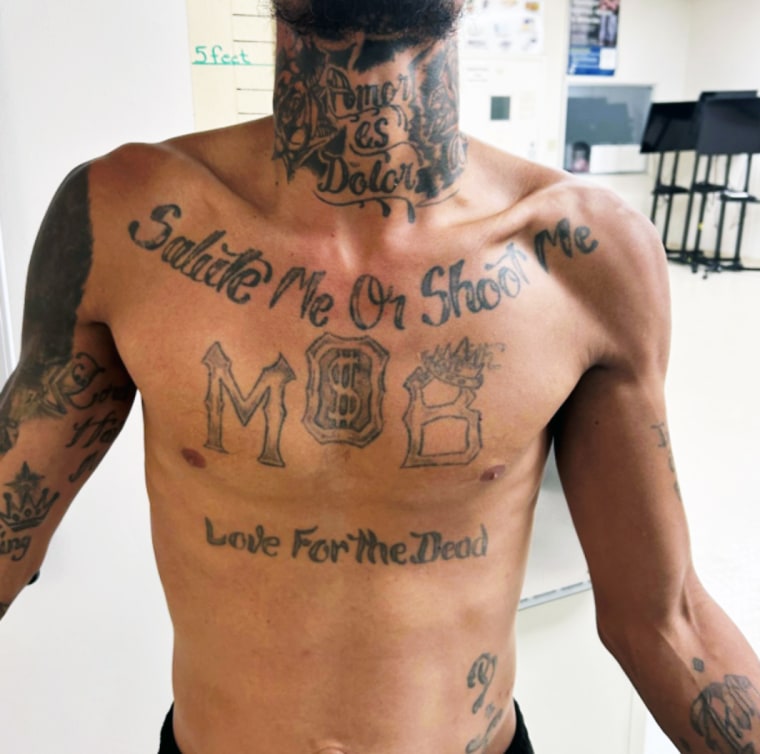

The NYPD calls them “ghost criminals,” with little to identify them except gang tattoos.

“Their identity may be misrepresented; their date of birth may be misrepresented,” said Jason Savino, assistant chief of detectives for the NYPD. “Everything about that individual could potentially be misrepresented.”

A surge of Venezuelans

During the Trump administration, border officials encountered about 3 million undocumented people crossing into the U.S. Though a breakdown by country of origin isn’t available for those years, the migrants tended to come from Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador and Mexico, all of which share law enforcement data with the U.S.

During the Biden administration, the number of people trying to enter the U.S. has risen to 10 million to date, and the composition of the migrant flow has changed.

About 800,000 Venezuelans have tried to cross since 2021, with the number surging from about 50,500 in fiscal year 2021 to 334,900 in fiscal year 2023. The influx posed a unique challenge for the Biden administration.

Not only does Venezuela not share law enforcement data, but it has also largely refused to take its nationals back on deportation flights. Some Venezuelans can be removed from the U.S. by land — under a 2023 deal, Mexico agreed to take back up to 30,000 migrants from Venezuela, Haiti, Nicaragua and Cuba monthly. But in some months, the number of migrants crossing from those countries has exceeded 30,000.

By last fall, Venezuelans were the majority of new arrivals to Chicago, New York and Denver, causing their Democratic mayors to raise concerns with the Biden administration about who was entering their cities and how they would be able to support themselves without draining local resources.

Some of the migrants who entered were affiliated with Tren de Aragua, and the gang has started to surface in criminal investigations in at least five states, according to local law enforcement officials. Homeland Security Investigations, or HSI, a law enforcement division of DHS, told NBC News it now has more than 100 ongoing investigations involving alleged members of Tren de Aragua.

Last month, HSI busted an alleged sex trafficking scheme in Louisiana, where members of the gang allegedly forced Venezuelan migrant women into sex work to repay the smugglers who brought them to the U.S.

In a federal affidavit, two of the women described how they were trafficked by three alleged gang members who had entered the U.S. within the past year. All three suspects had been intercepted by Border Patrol after they entered Texas illegally but had then been released into the U.S.

The women say the alleged gang members arranged for them to fly from El Paso, Texas, to Baton Rouge, Louisiana. Once they were in Baton Rouge, the women were taken to a Ross retail clothing store to buy clothes. They were then taken to an apartment building, where they were allegedly forced to have sex with four men a day.

The women say they were told that if they went to authorities, their families would be killed in Venezuela. One woman told HSI investigators that she believes gang leaders have already killed her mother, based on conversations with her relatives at home.

One of the victims alleged the ringleader of the operation was running similar operations involving 30 women in homes across five states, according to the criminal complaint.

The three suspected gang members are in federal custody and charged with sex trafficking.

Local law enforcement in Indiana is investigating a similar alleged sex trafficking network with suspected Tren de Aragua ties.

In January, Interpol disseminated an intelligence report to member countries that warned about the gang, calling it “a major regional security threat” throughout Latin America that has taken advantage of recent migration flows to expand its reach of criminal activities.

“While the group is well established in many South American countries,” an Interpol spokesperson said in a statement, “there is evidence that it is now expanding North, into Mexico and the United States, where key Tren de Aragua members have already been identified.”

How migrants are vetted at the border

When a Border Patrol agent encounters a migrant at the border, the agent asks the migrant for any identifying information, like a birth certificate or a passport.

The agent vets any information provided against a criminal database collected from U.S. agencies and foreign countries.

Blair said it can be challenging to verify identification. “Sometimes the smugglers will have them ditch their documents [so] they can declare a false name or a false nationality.”

If a criminal history is found, an agent can place a migrant on a fast track for deportation.

Misdemeanor crimes like driving while intoxicated may not always result in removal. But serious crimes like rape or assault bring referrals for prosecution or expedited removal.

In a statement, a DHS spokesperson said: “DHS screens and vets individuals prior to their entry to the United States. If an individual poses a threat to national security or public safety, we deny admission, detain, remove, or refer them to other federal agencies for further vetting, investigation and/or prosecution as appropriate.”

Despite the lack of cooperation from countries like Venezuela, said the spokesperson, the agency can check other available sources of information about criminal behavior, including data provided by law enforcement in countries that migrants may pass through on their way to the U.S.

A senior DHS official said CBP’s ability to screen migrants has improved over the past five years as the agency reached more agreements with other countries to share law enforcement information and has surged resources to vetting at the border.

Biden administration officials say that because they have increased and enhanced their vetting, they have expelled 4 million migrants so far, double the number deported under former President Donald Trump. The Biden administration prioritizes criminals and other public safety threats for deportation, but it isn’t clear how many of those deported have criminal records.

An NBC News review of public CBP data found more migrants with identifiable criminal records have tried to cross the border under Biden than under Trump, which tracks with the higher number of border crossings overall. The percentage of known criminals has changed little, however. About 64,000 of migrants stopped under Trump, or roughly 2%, were found to have criminal backgrounds. Under Biden to date, an estimated 103,000 of migrants were found to have criminal records, or just over 1%.

There is little hard data, however, about how much crime migrants are committing once they’re inside the U.S. What data there is doesn’t point to a migrant crime wave, despite political rhetoric and high-profile examples like crimes linked to Tren de Aragua. Criminologists have consistently found that immigrants commit crimes at a lower rate than native-born Americans.

Ari Jimenez, now a public safety consultant, investigated migrant crime in his former job with HSI. Jimenez said that while he sees the migrant flow at the southern border as an ongoing national security crisis, he is also concerned about what the actions of a dangerous few might mean for other migrants.

“Ninety-nine percent of people coming to the border have a legitimate reason for seeking asylum,” he said. “I don’t want a black eye on the migrants who are trying to make a living because of the 1 percent.”