A Lifepoint spokeswoman said in a statement: “Lifepoint Health is committed to a mission of making communities healthier, and we are proud of the entire team at Memorial Medical Center for the integral role they play in supporting the Las Cruces community.”

In 1989, when Memorial broke ground on the cancer center, city officials said the center “will be well serving the community,” minutes from a council meeting show. That community focus continued for decades; in 2010, five years after for-profit Lifepoint began operating the center, the indigent care policy explicitly included cancer care, a Memorial document states. Other documents, also on Memorial letterhead and produced under open records requests, show cancer care was first listed as an exclusion in August 2023.

Veronica Hernandez told NBC News she tried in 2019 to get treatment for breast cancer at Memorial but was repeatedly denied because she was uninsured. Although she ultimately got insurance, and help from CARE Las Cruces, to receive treatment at Memorial, the experience still rankles.

‘They don’t care about the community’

Lifepoint Health oversees the nation’s largest chain of mostly rural hospitals — 62 acute care facilities in 16 states — and is a subject of two U.S. Senate inquiries along with other health care companies owned by private equity, NBC News has reported. The investigations aim to assess the profits reaped by Apollo and other firms in the deals and whether they harmed patients and clinicians. Apollo has said it is cooperating with the inquiries.

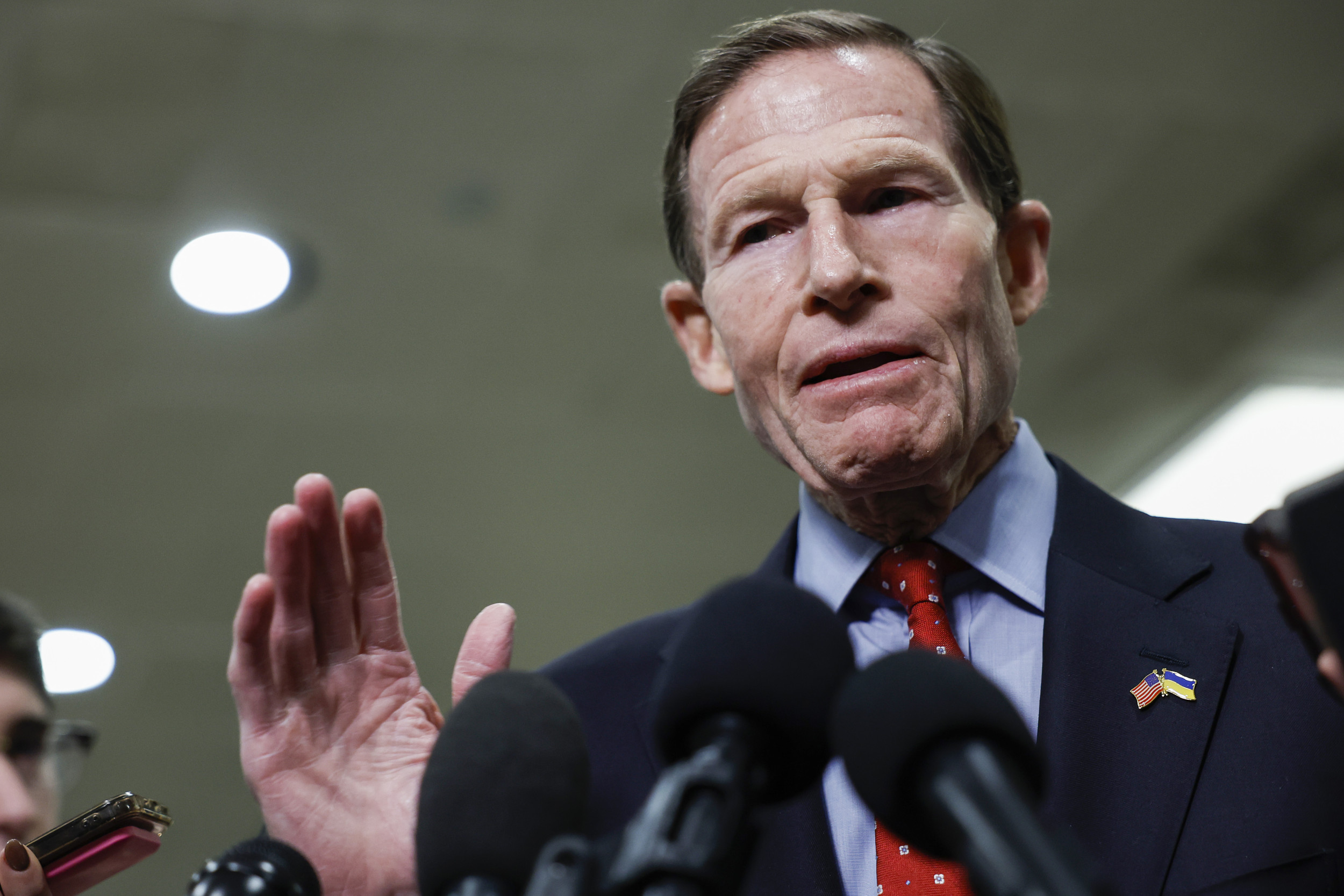

One of those investigations was launched last year by Sen. Chuck Grassley, the Iowa Republican who is the ranking member of the Senate Budget Committee, and Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse, the Rhode Island Democrat who chairs the committee. Grassley did not respond directly when asked about allegations that Memorial denies care, but said in a statement, “Every patient is deserving of the highest quality of care, including those in rural and underserved communities. Senator Whitehouse and I are taking a close look at how shifts in ownership may impact hospitals’ care. We’re fighting to ensure the medical system operates with positive patient outcomes at top of mind.”

Memorial’s longtime CEO, John Harris, declined multiple interview requests. On behalf of the hospital, another Lifepoint spokeswoman, Elizabeth Harris, (no relation) said Memorial has not received information requests from Senate investigators and that any changes to hospital policies “have always been done in close partnership with local government and community leaders.”

Hospital documents do not paint such a clear picture. While Harris said Memorial notified the city and county in July 2016 that it had begun excluding cancer care from services provided to indigent patients at a discount or shared cost, a September 2016 memo on hospital letterhead detailing the policy made no such exclusion. No further policy changes were documented in the public records reviewed by NBC News until 2023 when a memo on hospital letterhead noted the cancer care exclusion.

Becky Corran, a Las Cruces City Council member, said in an interview that the hospital has violated the terms of its agreement with the city and county about services it agreed to provide. The City Council has invited Memorial’s CEO to meetings over the past year to get answers, she said, but he has not shown up. “It’s a very clear sign they don’t care about the community,” she said.

Asked about Corran’s comments, Harris did not respond.

Private-equity firms like Apollo have taken over numerous health care companies in recent years. These firms typically load debt into the companies they buy, then slash costs to increase earnings and appeal to potential buyers in a few years. Almost one-quarter of New Mexico’s hospitals are controlled by private-equity firms, according to a study by the Private Equity Stakeholder Project, a nonprofit that analyzes the industry’s impact.

The American Investment Council, the private-equity lobbying organization, says the industry improves health care. But independent academic studies show private-equity firms’ involvement in the industry results in significant cost increases for patients and payers, such as Medicare. A lower quality of care has been associated with the firms’ investments in health care, research shows, including 10% higher mortality rates at nursing homes owned by private equity and greater incidents of infections, blood clots and falls at hospitals.

At Memorial, patients say the focus is on money. Jose A. Garcia told NBC News he had to pay $7,000 last year before he could receive treatment for kidney cancer because he was uninsured. Deborah Minser, who appeared at Memorial on May 1 for a follow-up appointment after cancer surgery, said she was turned away because her Medicaid coverage had temporarily lapsed that day. “They didn’t even say, ‘Let me call someone to work with you,’” Minser told NBC News. “They just said, ‘We can’t see you today.’”

‘Always a hassle’

The federal government defines indigent care as services provided to “patients whose health insurance coverage, if any, does not provide full coverage for all of their medical expenses.”

Memorial’s promotional materials say such care is central to its work. “Delivering care to all of our neighbors, regardless of their ability to pay, is foundational to our mission and our commitment to our community,” the hospital says.

That is not the experience Cynthia Arreola said she had when she approached Memorial in 2021 after receiving a breast cancer diagnosis. She had insurance, but the hospital demanded she pay her deductible up front, she said, before she could get an appointment.

“It came down to, ‘If you don’t have money, you cannot have the scans or MRI,’” Arreola, 41, recalled in an interview. “I had to have my family help me come up with that money and get my testing done so I could start my chemo.”

She said dealing with Memorial was “always a hassle, a battle.” So, she found a cancer clinic in El Paso that offered a financial assistance program and let her pay what she owed after she received care. “I ended up moving somewhere else because I had the pressure of cancer and the monetary pressure,” she said. She also said the charges for treatments in El Paso were roughly one-quarter of what Memorial charged.

Memorial’s financial results are not public, but data from CMS supports Arreola’s view of its costs. In 2021, the most recent figures available, Memorial charged 6.7 times its costs for care. The average among for-profit hospitals across the U.S. is less than five times, according to Ge Bai, professor of health policy and management at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health in Washington, D.C.

The CMS hospital comparison site confirms Medicare costs per beneficiary at Memorial are both higher than the national average and almost 20% higher than the state average. Even so, Memorial received two stars out of a possible five in overall quality, the site said.

Not surprisingly, Memorial has been profitable, CMS data shows. In 2021, it reported $28.5 million in net income on service to patients, a 9.3% profit on net patient revenues of $305.6 million. That’s well above the median 6.5% margin reported at a sample of more than 4,000 hospitals during the period.

Lifepoint spokeswoman Harris said it would be “more fitting” to compare Memorial’s charges with other hospitals in the region levying similar or higher costs. Across the state, there are 12 hospitals serving communities like Memorial’s and six of them lost money in the period according to data from the Center for Healthcare Quality and Payment Reform, a nonprofit that advocates for improvements in health care payment and delivery systems. Of the other five that made money, their profit margins averaged 14.5%.

Even as Memorial charges patients well over its costs, it ranks low in community benefits, according to the Lown Institute Hospitals Index — a measure of a hospital’s contributions to the population it serves. Memorial received one star out of five in financial assistance programs for the indigent or underinsured and ranks 28 out of 32 hospitals in New Mexico for benefits to the community, according to Lown, a nonprofit.

Harris did not comment on the Lown ranking.

Dona Ana County, the urban and rural region Memorial serves, has a population of 225,000 and almost 15% have no health insurance, recent census figures show. Some 23% of county residents live in poverty, compared with 11.5% nationwide.

Memorial said it has donated more than $150 million in health care services to benefit the community from 2020 through 2023. In a 2021 report, Memorial said it donated more than $32 million “to those in need.”

Asked for a breakdown, Memorial told NBC News that $1.7 million was charity care, defined as health care provided without any attempt to receive payment. A far greater amount — $18.3 million — consisted of forgiveness for bad debt, or health care for which Memorial had tried unsuccessfully to receive payments. Another $11.1 million consisted of “uninsured discounts,” or unpaid amounts for care based on what the hospital charges above its costs.

“For indigent care patients, charity care is the more relevant number,” Bai of Johns Hopkins said, regarding Memorial’s contributions. “Uninsured discounts is a bogus number that just discounts off the hospital’s charges,” such as the $670 Memorial charges for care that costs it $100 to provide. CMS does not consider bad debt forgiveness to be charity care contributions, she said.

Health care experts assess charity care by comparing it to a facility’s total expenses, and under such a calculation Memorial’s $1.7 million in charity care is low, research shows. The average for-profit hospital in the U.S. provided charity care equal to 3.8% of its expenses, according to research published in Health Affairs in 2021. At Memorial that year, charity care totaled just 0.54% of its expenses or about one-half of 1%.

Harris, the Lifepoint spokeswoman, said comparisons to national levels of charity care are “difficult” because more of Memorial’s patients are on Medicare or Medicaid. Memorial does not authorize collection agencies to sue patients with past due balances and does not report balances to credit bureaus, she added.

‘Come up with $2,000’

In 2022, Nancy Skinner’s doctor ordered a biopsy to assess a growth in her left leg. A longtime Las Crucen, she went to Memorial for the service but because she had only Medicare Part A insurance coverage, the hospital balked. “They said, ‘You have to come up with $2.000,’” she said. “Pay that and we’ll do the procedure.” She said she had to take out a bank loan.

After receiving the results, she needed a PET scan. Memorial said it would schedule her if she paid $1,600, she recalled. “I said, ‘Can I make payments?’ They said no,” she said. A friend paid the cost.

Skinner said she received excellent care at a University of New Mexico hospital in Albuquerque that had no problems with her insurance. But she wanted to have radiation treatments closer to home. She signed up for Medicare Part B as soon as she could in 2023.

Delays in cancer care can jeopardize a patient’s life. Still, she said, Memorial refused to treat her until its computer systems showed her Part B application had gone through. “I don’t know who’s making these decisions but they’re not looking out for our best interests,” she said. “I spent four months begging them, but they didn’t seem to care.”

Robert Garza, a former Las Cruces city manager, sat on the board of Memorial for 16 years beginning in the early 2000s. After he retired, CEO Harris invited him to rejoin the board representing the community, he told NBC News. Garza stayed for three more years, becoming board chairman.

Garza said the hospital’s indigent care program was working well under a program with funding from the county and federal government. That changed after the Affordable Care Act passed, he said, and government money disappeared. The hospital had to eat what he said was $6 million a year in indigent care costs.

He said he thinks the hospital is not violating the lease, which requires the facility to continue providing services as long as there is “no major adverse change in funding” at the facility. Garza said he thinks the ACA represented such a change.

Others aren’t so sure. A July 2023 memo from the Las Cruces city attorney that noted patients had been alleging denials of care says a determination that the hospital was violating the lease “would depend upon a number of factors and require an analysis.” Garza predicted the matter will likely end up in court.

Such an outcome has occurred at two other formerly nonprofit hospitals far from Las Cruces. Last year, the North Carolina attorney general sued HCA Healthcare over its 2019 acquisition of Mission Hospital in Asheville, and in 2022, The Foundation for Delaware County sued Prospect Medical Holdings, owner of Crozer Health Systems, a four-hospital chain in the Philadelphia area. Both facilities were accused of failing to provide the care they promised when they converted to for-profits.

HCA is fighting the case and Prospect, owned by private equity until 2021, is trying to sell the Crozer hospitals to a nonprofit.

Corran, of the Las Cruces City Council, said city attorneys are looking at the hospital agreements to evaluate next steps. To Diaz, of CARE Las Cruces, Memorial, the city and county have betrayed the community. “Everybody has turned their back,” she said.

Hernandez told NBC News she felt betrayed when Memorial turned her away for breast cancer treatment. Then, in mid-May, a few weeks after NBC News told Memorial about her experience, Hernandez received a surprising phone call.

Two women were on the line — Memorial’s director of admissions and the head of the cancer center. What did they want? To apologize, Hernandez said. Minser, another patient, also received a phone call from the women apologizing.

“Because we are making noise that they don’t like,” Hernandez said. “That’s why they apologized.”