As a rising high school senior trying to figure out the next several years of her life, Gabrielle Wilson sees Thursday’s Supreme Court decision on race-conscious admissions as a possible hurdle.

“I think if affirmative action was taken away, it would make me not as hopeful about getting into the higher institutions I would like to apply for, such as Harvard,” said Gabrielle, 17, who will be a senior at the private De La Salle Institute in Chicago this fall.

Gabrielle spoke to NBC News before the Supreme Court decision Thursday that vastly restricts race-conscious admissions.

The process, also known as affirmative action, allowed schools to consider an applicant’s race as a factor in determining admission, with the goal of creating a racially diverse student body. The court ruled on cases challenging the practice at two selective colleges, Harvard and the University of North Carolina.

The group Students for Fair Admissions Inc., led by the conservative activist Ed Blum, who is white, said the universities’ admissions policies discriminate against Asian Americans and — in the case of UNC, white applicants as well — and favor Black and Latino applicants. Meanwhile, experts have long considered affirmative action at the nation’s more selective schools to be key in helping aspiring college students counteract inequities they may have faced throughout their K-12 education.

Students of color in high schools across the country spoke to NBC News, sharing a range of concerns in the lead-up to the ruling. What was on their minds: whether they should adjust their list of application-worthy schools, confusion about the ruling itself and, in some cases, if they should completely ignore the court’s decision. Meanwhile, academic experts say they foresee ways the ruling may have broader implications beyond just eliminating race as one factor for college admissions.

Black students won’t rule out predominantly white schools — or HBCUs

Gabrielle said she plans to apply to University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, a predominantly white school, and Spelman College, a historically Black college in Atlanta, among other universities including Harvard.

“I think that I would still apply because I have confidence in myself and you never know what the outcome will be unless you try,” she said of predominantly white schools, “but I do think I would lack a little confidence in getting in.”

Sari Zinnerman, a 17-year-old rising senior at Homewood-Flossmoor Community High School in Illinois, said she is looking toward Spelman College or Howard University, both of which are part of the group of schools known as historically Black colleges and universities, but, she added, “even though I am not interested in attending a prestigious predominantly white university, I am confident that with my stats and community service outreach that I would be able to attend a predominantly white university.”

Her twin sister, Sani, had a differing view.

“I do not plan on changing my college choice because of the faith I have in HBCUs,” she said. Sani and Sari both won AP Scholar awards in 2022 for high achievement on college-level Advanced Placement exams. Sani said her top choice is Spelman College.

“I do not have confidence that I will get into my backup schools,” which are predominately white institutions, “although I have perfect stats,” she said. Both Sani and Sari are part of Plan4Success, a mentoring organization that provides college preparation resources to students in Chicago.

At 47%, Black Americans are more likely than other racial groups to say selective colleges should consider race and ethnicity in admissions, according to a Pew Research Center survey published earlier this month.

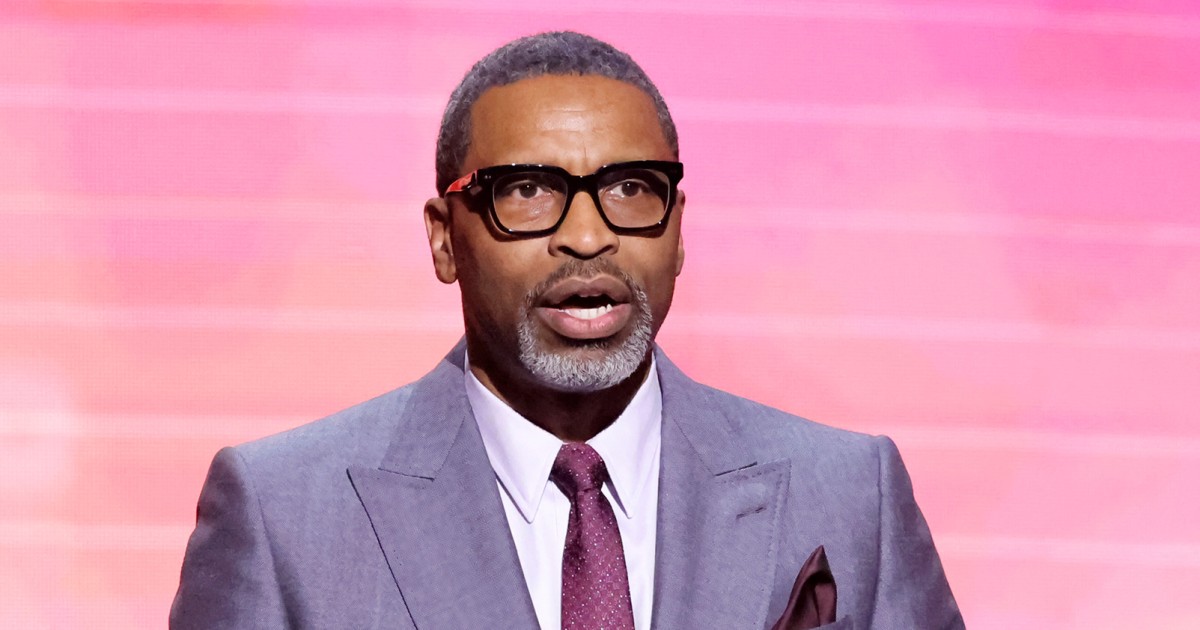

Applying to HBCUs has been a common response among Black high school students planning for the potential demise of affirmative action. HBCU leaders like Danielle R. Holley, the dean of Howard University School of Law, and Ronald Mason Jr., the president of the University of the District of Columbia, have said HBCUs will become even more integral in the push for diversity as they become the example of racial equity in the U.S.

“A lot of Black students are being drawn to HBCUs,” Plan4Success executive director Nicole Brookens said of the teens who are part of her organization. “Nonprofit organizations that help mentor students to be conduits to their success” will be “vital,” with the dismantling of race-conscious admissions at selective schools, Brookens added.

The students shared similar sentiments, decrying the end of affirmative action in college admissions. Sani said she does not believe that “universities can be diverse without affirmative action due to them being run by majority white people who do not always have the best interests of our community.”

Gabrielle, who is also part of Plan4Success, added: “I think that if affirmative action was to go away, the diversity of schools would decrease and we would see the Black population be poorly represented” on college campuses. “I think that affirmative action is the requirement needed in order for institutions to be fair and accumulate a large Black population,” she said.

The ruling’s potential ‘chilling effect’ on Latino students

Josué Coronado, 26, was born and raised in Houston and is from a Mexican American, working-class family. “Georgetown changed my life,” the former teacher and current educational recruiter said about his undergraduate university. He also has a Master of Science in education from Johns Hopkins University.

“I’ve benefited from these programs that were intentionally focused on getting people like me — from my background — to institutions like Georgetown,” Coronado said. “I would say we definitely have to think about race, about culture and about socioeconomic status, because those three things very much determine how people treat you in this country.”

Latino students now make up at least 25% of K-12 public school students in the U.S., but they’re underrepresented in the nation’s top colleges and universities. Their numbers also lag across states’ flagship universities, which often have better resources, alumni networks and four-year completion rates than other state institutions.

While the Supreme Court ruling struck down race as a factor in admissions, it doesn’t limit an institution’s outreach efforts to diversify its student body. Still, experts are concerned about how students and families may interpret the decision.

One result of the decision may be “the chilling effect of students who feel like they don’t belong,” like their identity doesn’t matter, said Deborah Santiago, the co-founder of Excelencia in Education, which measures and promotes college programs that result in greater Latino graduation rates. “Historically, the institutions have not reached out to us. And so I do think that’s real for our students.”

Andrew Salas, 17, a rising senior at Bishop Mora Salesian High School in Los Angeles, isn’t sure how the decision on affirmative action will affect him. But he thinks race as well as class are important factors in a student’s background and worries about what the decision could mean.

”To just not be taken seriously — that’s kind of my biggest fear,” Andrew said.

The Pew survey found that Latinos are divided on the issue of affirmative action, with 39% in support, 39% against and 20% not sure.

But experts who support the use of race as a factor in admissions point to history: When some states such as California banned the use of race in admissions, the enrollment of Black and Latino students in the state’s more selective colleges declined.

Following the decision, “we would need to keep a close eye on how our students are faring in admission decisions and we need to continue examining which factors colleges and universities are assigning the most weight to,” said Jasmin Pivaral, director of college culture at the Partnership for Los Angeles Schools. “But focusing on students also assumes that the onus falls on them. … We need to make sure that university leaders are examining how their current systems and structures are inequitable, and they must make strides in addressing those inequities.”

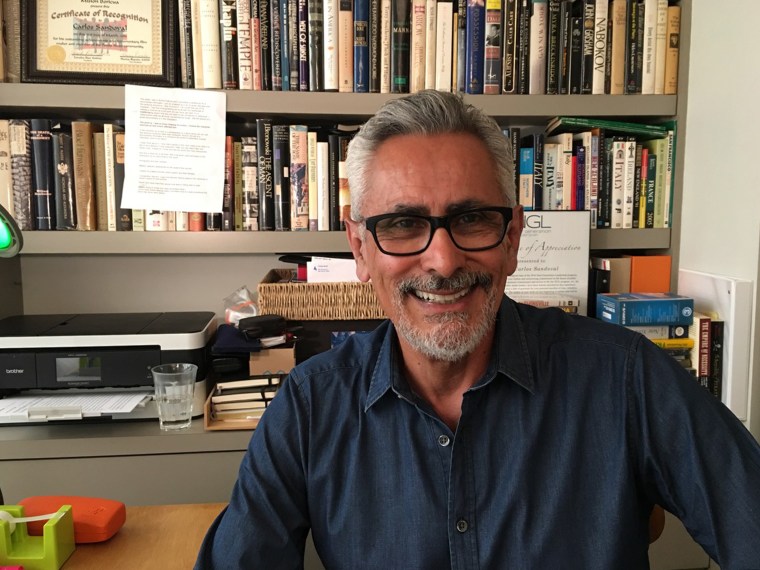

About a half-century before Coronado, Carlos Sandoval entered the Harvard class of 1970. The Sundance winner and Emmy-nominated documentary filmmaker, who came from a working-class family in Southern California, recalled being one of the only Mexican Americans on campus.

“I’m certain my admission came at the cost of some better academically qualified Anglo student, but I also wonder if that student could have surmounted what I had to in order to get into Harvard and then graduate with honors,” Sandoval said. He noted that “along the way” he was elected president of the Freshman Union Committee, became an adviser and helped establish Harvard’s first gay undergrad organization. “Harvard took a chance on me, and I’d say that, though it took me some time to find my footing, it paid off.”

For Asian Americans, diverse beliefs and some ‘misinformation’

Asian Americans have mixed feelings about the policy. Some say they feel white activists are using the community as a “wedge” against other minorities to fight against affirmative action. Others feel that the policy has put them at a disadvantage, removing merit from the process. Still others say the loudest discourse obscures the fact that many Asian Americans are low-income and benefit from the policy as well.

Pew’s survey showed that 53% of Asian Americans who have heard of affirmative action say it’s a good thing, while 19% say it’s a negative thing.

Another 2022 survey from nonprofit group APIA Vote, which polled registered Asian American voters, showed 69% favored affirmative action programs “designed to help Black people, women, and other minorities get better access to higher education.”

Hera Kim, 17, a Korean American public school student in Northern Virginia, said she’s been a supporter of affirmative action policies as a way to promote diversity and expand access.

Hera, who’s hoping to major in fine and studio art, noted that the issue has long been debated in her community. She said she thinks that many opponents are guided by the “misinformation” that “racial consciousness in the admissions process is inherently racial discrimination.”

“It runs on this idea of a scarcity mindset,” Hera said. “It presents this illusion that when Latinos and African American students are given these equal opportunities due to affirmative action, it’s presented like those seats for those students are coming out of seats for Asian American students.”

She added that if “more of us were able to look past the politicized debate over affirmative action, and truly understand what affirmative action has done historically for all minorities, I think that we would have a better understanding of why it is an integral part of our admissions process.”

Many of those in opposition, experts explain, have been fueled by factors like their experience with test-focused school systems in Asia, class anxieties, the immigrant condition, and a lack of firsthand knowledge of the United States’ racial history.

The opaque nature of admissions processes can make many Asian parents and students believe there’s discrimination at play, said Natasha Warikoo, author of “Race at the Top: Asian Americans and Whites in Pursuit of the American Dream in Suburban Schools.”

“I remember speaking on a panel years ago at one of these exam schools and an Asian American woman stood up and said, ‘You know, just as we figure out your system of meritocracy, it feels like you’re pulling the rug from underneath us,’” Warikoo said.

Though much of the education debate has centered on Asian Americans at highly selective private institutions, a higher share actually attend schools that may not be directly affected by the ruling. In California, for example, 41% of Asian Americans in 2020 started their higher education careers at community colleges, more than any other university system.

Mercuri Lam, a 17-year-old Chinese American who uses the pronouns they and them, said they’re in favor of affirmative action because it’s expanded opportunities for low-income students like themself. Mercuri, whose parents didn’t go to college and immigrated to the U.S. from China when Lam was 8, said affirmative action helped them earn their scholarship at their current private high school.

“It’s been said to me before that I only got into this school because I was queer or because I was Asian or because I was a first-generation immigrant,” Lam said. “But in reality, if I wasn’t admitted because of that, I wouldn’t even have those opportunities.”