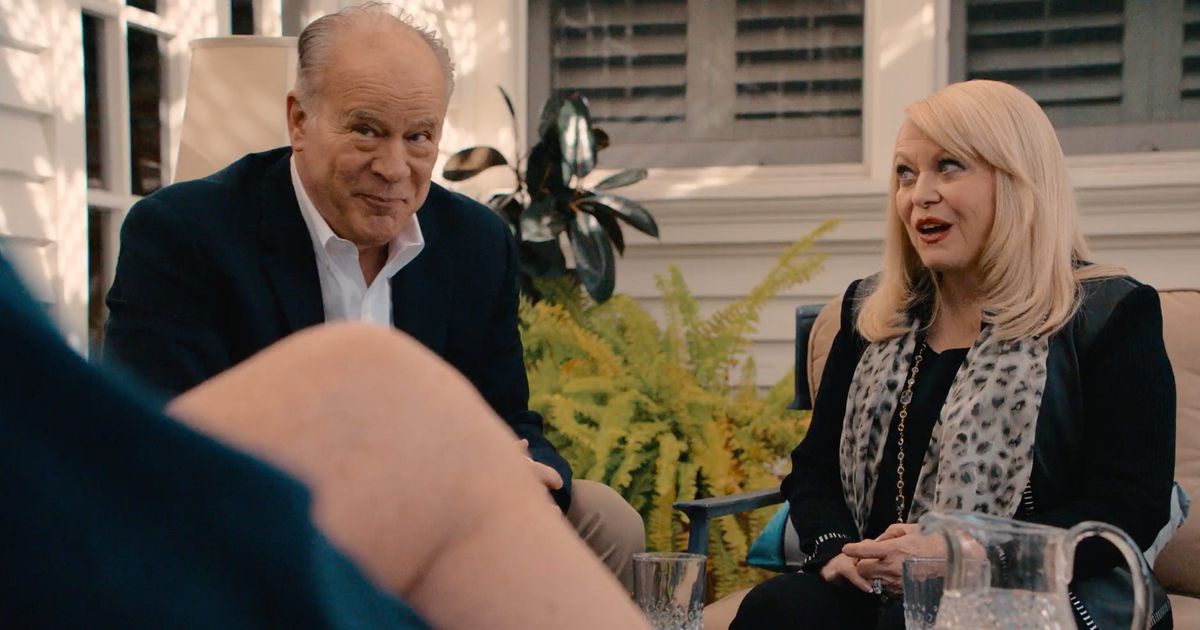

Photo: Courtesy Hulu

Late in the finale of Clipped, Shelly Sterling examines a newspaper headline. “So sad,” she says, shaking her head. She drops it in her husband Donald’s lap as he’s out sunbathing in the nude, looking about as unbothered as a person could be, particularly a man who just spent a week humiliating himself in the public eye. The headline: “Ferguson Proves Transformative.” And that’s the last we see of Mr. Sterling in the series.

It may not be the subtlest moment, but it’s significant for plenty of reasons, not least of which is that “Keep Smiling” is co-written by Rembert Browne, whose Grantland piece “The Front Lines of Ferguson,” about his participation in the Michael Brown protests as both as a journalist and a Black man, remains one of the most important pieces of writing about this galvanizing standoff in Missouri. There’s some degree of ambiguity in Shelly saying “so sad.” A generous person might read her as concerned over the deep racial injustices that still haunt the country. (Though that same person would probably not want to hear her get into further detail.) The point here is that the Sterlings could not be more insulated from Ferguson, even though they’ve made more than their fair share of contributions to the problem.

Also relating to the episode is this key passage from Browne’s article:

The history of being Black in America is the history of nonviolence versus “fight back.” Of wait versus now. Of a turned cheek versus self-defense. Suddenly, this was becoming the latest chapter in Black America’s “what next?” history.

That’s the Doc Rivers dilemma. And the Elgin Baylor dilemma. The dilemma faced by the Los Angeles Clippers during a season when they were talented enough to keep their heads down and compete for the championship that had long eluded the worst franchise in professional sports. Baylor chose nonviolence for years before fighting back against Sterling in the courts, albeit fruitlessly. Here, Doc and his players are haunted by the decision they made when they might have done more to wrest control of the Sterling situation while shaking up the league and country. That ineffectual demonstration at center court, combined with the “We Are One” sloganeering of the front office, was not sufficiently disruptive. In a conversation with Doc, Chris Paul references Tommie Smith and John Carlos raising their fists in a Black Power salute from the podium at the 1968 Olympics in Mexico City. The blowback for their demonstration was devastating at the time, but they’re remembered for their courage on the international stage. That’s not how people will remember the Clippers wearing black socks and turning their warm-up jerseys inside out.

(Rivers didn’t cover himself in retrospective glory after the game, either. “I knew about it. I didn’t voice my opinion,” he said about the protest. “I wasn’t thrilled about it, to be honest. But if that’s what they want to do, that’s what they want to do.”)

And yet, the show does well to imply a question to the viewer: How much criticism do Rivers and the Clipper players deserve for not responding more forcefully to Sterling’s racism? The quandary that Browne describes in his Ferguson article between “wait versus now” and “turned cheek versus self-defense” is laid out plainly for the Clippers’ personnel well before the Sterling tape was released to TMZ. Everyone knew who Donald Sterling was. For Doc and the players, it was a devil’s bargain to play under Sterling just as it’s often a devil’s bargain for Black people to try to realize their dreams and ambitions in a racist system. Coming up with a proportional response on the fly wasn’t easy, especially for a team that had disciplined itself to cut out the noise. It’s not for nothing that Doc’s angriest moment in Clipped is when Sterling just strolls into the locker room after a game. That’s the one sacred space they’ve carved out for themselves.

In its busy finale, Clipped finally puts Shelly Sterling in the crosshairs after allowing her a certain amount of room to play victim to her husband’s infidelity and more obvious, unhinged racism. Given a short time frame to sell the team to the highest bidder between Adam Silver and the league do it for her, Shelly starts taking suitors for a franchise that had spiked 16,000 percent on the Sterlings’ original $12 million investment, despite Donald’s serial mismanagement of the organization. She welcomes Patrick Soon-Shiong, the billionaire who now owns the Los Angeles Times, with “every sushi you can name.” Other names like Oprah Winfrey and David Geffen surface, along with Sterling’s nemesis, Magic Johnson, who she knows her husband will not approve under any circumstances. The most promising bidder calls her in the middle of the night: Steve Ballmer, worth over $20 billion in Microsoft money, is ready to fork over $2 billion in cash for the Clippers, and Shelly is delighted by his offer and his famously boisterous personality.

The main obstacle to the sale is Sterling himself, who grumpily entertains Ballmer’s pitch without any intention of accepting it. (“What an idiot to keep that [money] in cash,” sneers Sterling. “He’s not the guy.”) So, Shelly and her lawyers turn to “Plan B,” which exploits an amended line item in the Sterlings’ trust that gives her full control of their assets should Donald be found incompetent. His shockingly vile interview with Anderson Cooper, where his brief and unpersuasive show of remorse leads into a diatribe against Johnson, adds fuel to the fire, but Shelly’s sneaky use of a cognitive test to expose his dementia gives her the edge in court. (And yes, Sterling really did say, “Get away from me, you pig,” to his wife loudly enough after his testimony to enter the record.) In the end, she succeeds in executing a record sale and buttressing her “nice old lady” image in public.

Clipped doesn’t let her get away with it. For one, there’s the fallout for V. Stiviano, whom Shelly sets out to destroy in a “hell hath no fury” vendetta that mostly serves to kick V. while she’s down. Already branded a loser in the public relations war that drains her coffers in legal fees without the famous-for-being-famous payoff she’d expected, V. faces a lawsuit from Shelly over the $2.8 million in gifts, including a duplex and cars that Sterling had given her during their time together. Before a racist barroom assault that bruises her meticulously managed face, V. tells her friend that she’s living in an Airbnb in Van Nuys, though she’d been offered a job at a Cingular wireless store in San Antonio. Her humiliation and financial ruin doesn’t need to be deepened, but the courts work for rich people like Shelly Sterling and she doesn’t stand a chance.

At a posh hotel lunch, Clipped finally gives Shelly a well-deserved comeuppance, albeit with a healthy amount of dramatic license. First, her friend Justine turns on her over the V. lawsuit and her plan to “give” the duplex to her housekeeper Gladys, even though Gladys won’t really own the place. Justine calls Shelly out for not really being serious about her divorce and assuming the same attitude about her supposed generosity to Gladys as her husband did about V. and everyone in the Clippers organization. (“You two were made for each other. You both think you own everybody.”) Then Doc, who’d shown sympathy for Shelly throughout the ordeal, comes along to question her claim that she sacrificed anything in selling the team. Under the deal with Ballmer, she still gets 12 tickets for every game, VIP passes, and other perks, including three championship rings if the team ever wins the title. So, the punishment for her own complicity in Sterling’s racism is nonexistent.

The final scene pays homage to Baylor, who suffered Sterling’s abuses the longest and the hardest. After all, it’s one thing to hear the man’s views exposed to the public on tape but quite another to work under him for 22 years as the GM. Putting up shots with Doc, Baylor takes a while to get his muscle memory back and find his form. “I need to shoot ’til it sounds right” is the show’s last line. Guys like Doc and Baylor surely feel like they weren’t perfect in responding to a boss like Sterling. But the pursuit of that right-sounding swish is meaningful.

• The LeVar Burton device never functions as more than an awkward device to get inside Doc’s head, but Burton’s story about keeping the chains from his performance as Kunta Kinte in the 1977 miniseries Roots allows for an elegant piece of racial commentary: “I keep my chains on the wall in my living room. I want my guests to know that while I am unquestionably their friend, I am also absolutely filled with rage.”

• Perhaps the West Coast Donald Trump comparison is too tidy, but when Sterling lashes out at Anderson Cooper about racism (“I think you have more of a plantation mentality than I do. I think you’re more a racist than I am”), it sounds exactly like Trump calling himself “the least racist person” in the world. And, to extend the analogy further, the popular idea that Melania, like Shelly, detests her unfaithful and boorish husband misses the more straightforward reading that both couples are still married and likely share each other’s points of view.

• There’s not a lot of laughs in this episode, but Sterling interrupting his own lawyer in court to complain about his wordy objection is a funny bit of self-immolation, capped by Shelly pleading with him from the stand to cool off.

• That terrible story about Doc Rivers’s home getting burned to the ground in what he believes was a racially motivated attack is true and more important context for his actions during the Sterling affair.

• Complaining about “the Obama tax” in a 16,000 percent return on investment sounds like classic billionaire behavior.