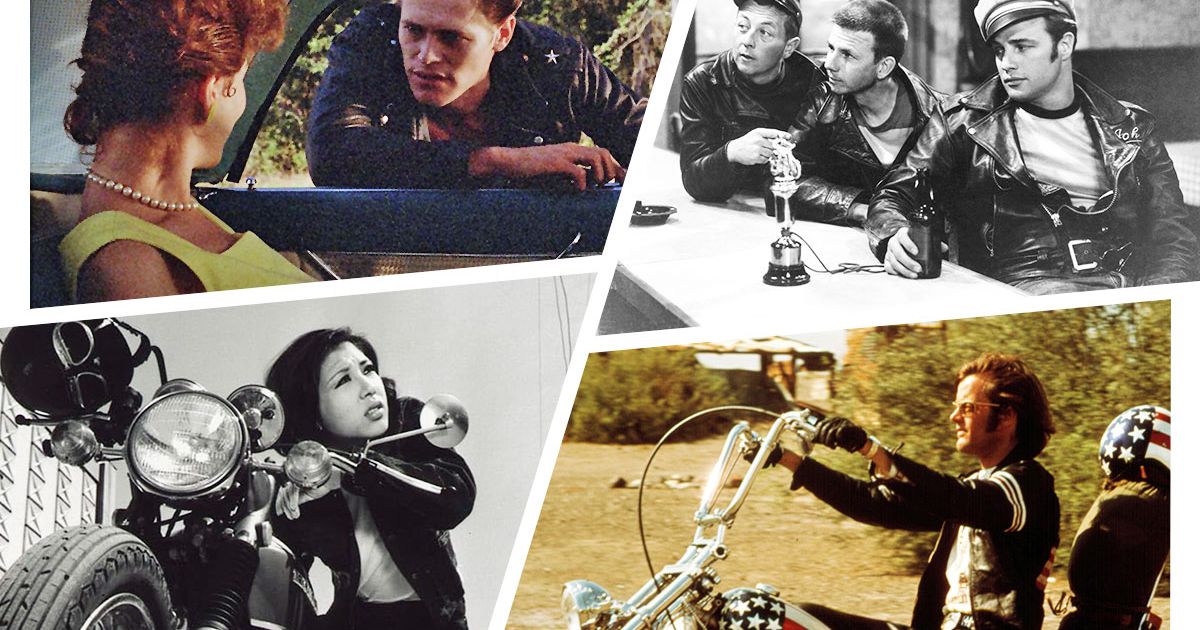

Photo-Illustration: Vulture; Photos: Atlantic Releasing, Everett Collection, Nikkatsu

In 2024, The Bikeriders is an anomaly. The only biker gangs to appear with any regularity in 21st-century movie theaters are in the postapocalyptic Mad Max saga, and even they only come around about once a decade.

With that in mind, it’s no surprise that writer-director Jeff Nichols reached back into the past for his drama about the fictional midwestern motorcycle outfit Vandals MC. Because in 1967 — the year Chicago photographer Danny Lyon released the pioneering photobook on which The Bikeriders is based — the denim-clad specter of the outlaw biker was everywhere. And so were titillating “cautionary tales” about these motorcycle-riding hellions and their hard-partying lifestyle.

The bad-boy loner had already entered the pantheon of American sexual archetypes by the time the biker-movie trend took off in the mid-’60s, thanks, in part, to Marlon Brando’s smoldering turn in The Wild One. (James Dean riding motorcycles — and dying young and sexy in a flaming car crash — didn’t hurt, either.) That film was released in 1953, only five years after the establishment of the Hells Angels. And biker flicks were made, here and there, in the meantime. But it was Roger Corman and The Wild Angels that made them their own subgenre.

The success of Corman’s typically on-trend 1966 movie prompted a wave of outlaw biker pictures, many of them produced by Wild Angels studio American International Pictures or Corman’s own outfit, New World Pictures. (AIP was a clearinghouse for up-and-coming talent: Dennis Hopper, John Cassavetes, and Jack Nicholson all starred in AIP biker movies.) The following year, both Lyon’s The Bikeriders and Hunter S. Thompson’s Hells Angels: A Strange and Terrible Saga were published, and outlaw bikers’ dual roles as Middle American bogeymen and counterculture icons were set.

In 1969, Easy Rider changed the game again by bringing bikers into the cinematic mainstream. The murder of 18-year-old Meredith Hunter by members of the Hells Angels at the Altamont Free Concert that summer should have changed things as well, but it didn’t — at least not onscreen. It wasn’t until the mid-’70s that the stream of movies with “Angel” in the title — a reference to the notorious California-based outfit — slowed to a trickle. The vibes are noticeably worse in these late-period entries: Vietnam and Charles Manson both hang over the action, as they did the counterculture in general post-1969.

Biker fashions of this era come in two basic types: The traditional black leather and cat-eyed sunglasses look of mid-’60s girl gangs, and furry guys in grimy denim vests who just look like they stink. (When real Hells Angels appear in movies, they’re easy to spot, as they’re much dirtier than the professional actors.) They all smoke a lot of pot, drink a lot of beer, and practice free love within a rigid sexist framework. “Mamas” are “passed around” at the direction of male gang members, but it’s groovy because they like it — or so they say. With that in mind, the pervasiveness of sexual violence in these films should not be a surprise.

The thing that’s aged the best about outlaw-biker movies is their lack of interest in work and hatred of the capitalist system. The worst is all the Nazi crap. A scene early in The Wild Angels illuminates outlaw bikers’ fondness for fascist imagery, as a WWII veteran played by Dick Miller angrily curses Bruce Dern’s character for wearing a swastika on his helmet. “We used to kill guys who wore that kind of garbage,” Miller says. Dern smiles. To ’60s bikers, swastikas didn’t signal allegiance to the Nazi cause, per se, but a broader antisocial tendency. They did it to piss people off, in short — reasoning that, like calling the Confederate flag a symbol of “southern pride,” is ultimately just an excuse to be hateful in public.

Biker culture morphed as it spread abroad, sparking distinct regional variants in the U.K., Australia, and Japan. In 1979, Australian George Miller changed the game yet again with Mad Max, which inspired its own batch of imitators; in the ’80s, postapocalyptic sci-fi variants on biker gangs became more popular than their reality-bound contemporaries. It’s stayed that way, although the erotic appeal of roaring engines and misunderstood rebels remains as potent as ever. With an eye for palatability, relevance, artistic (and camp) value, and just plain fun, here are 15 of the best outlaw-biker movies the subgenre has to offer.

With the caveat that this movie fetishizes Native Americans as “noble savages” while casting a blue-eyed white guy as the “Indian” hero, The Savage Seven is tame for a ’60s biker movie. (The weirdness of the white ’60s counterculture toward Native people cannot be overstated.) It’s a Dick Clark production, for Chrissakes — the American Bandstand host only allowed so much debauchery in his brand of “youth culture.” And so the bikers in this film, led by genre regulars Adam Roarke and Larry Bishop, are a little more well scrubbed than usual. This is both good (no sexual assault, always a plus) and bad (these outlaws are downright cute at times, which makes them less believable). All in all, it’s a strange but satisfactory ride with tracks from Cream and Iron Butterfly on the soundtrack and cinematography from a young “Larry Kovács.”

On the other end of the spectrum is Satan’s Sadists, the first and most popular biker movie directed by notorious exploitation filmmaker Al Adamson. The shadow of Nam hangs over this harsh but unintentionally hilarious film, in which a cop from Pittsburgh and his wife, along with a Marine and a waitress putting herself through college, fight back against predatory bikers at an isolated desert café. Russ Tamblyn stars as Anchor, the leader of said gang, giving orders from beneath a floppy wool hat and sunglasses. His “Satans” include a guy with an eyepatch, an extremely tan biker chick whose hair is bigger than she is, and a Native American guy named Firewater. (Told you.) The filmmaking is incompetent enough to give it an otherworldly feel, but not so incompetent as to be unwatchable, which helps sand down the movie’s rougher elements — and there are a lot of them.

Co-directed by producer Monty Montgomery (a longtime Lynch collaborator who played the Cowboy in Mulholland Drive), Kathryn Bigelow’s debut feature shares a dangerous sexuality and western feel with her six-years-later followup, Near Dark. The film is set in the South but has the feel of a western with bar brawls and high-noon showdowns, which combine with ’50s juvenile-delinquent aesthetics (think teased hair, smacking gum, and cars with fins) for a heady sensual experience. This movie hinges on the bad-boy sex appeal of Willem Dafoe as Vance, a member of a biker gang whose intensity proves so irresistible to a small-town girl that their lust ignites a conflict of Shakespearean proportions. Bigelow is still finding her feet as a filmmaker, and The Loveless barely hangs together as a narrative. Maybe she was driven to distraction by all the musky leathers and hot chrome.

Compared to its contemporaries, the otherwise obscure Angels From Hell has aged well thanks to its hardline anti-cop stance. This ACAB western opens with crude hand-drawn graphics of cartoon pigs, one wearing a gold medal that says “Petty Tyrant Award.”

The story takes us to a dusty highway somewhere inland from Los Angeles, where Mike (Tom Stern) returns from Vietnam to find that his old gang has been taken over by a bootlicker who is chummy with local law enforcement. This will not stand, so Mike and his cronies set out to unite the bikers of California to defend their outlaw way of life — which largely revolves around partying in desert shacks and smoking joints with movie producers, but whatever. (Hollywood types always have weed on them.) The action is cartoony, and the plot is thin, but the spirit is righteous.

The British oddity Psychomania combines the horror and biker genres, tying in the parallel witchcraft craze of the early ’70s for a delightful occult streak that manifests in misty visions in magic mirrors and arcane pacts with the Devil. The plot itself is very dark: A witch’s son commits suicide, and, after a graveside hippie sing-along, she resurrects him using black magic that gives him power over life and death. This turns him into a sort of Thanatos Tinkerbell, who tells the members of his biker gang — ironically already named the Living Dead — that if they believe hard enough and drive their bikes into a wall, they’ll come back immortal and more evil than ever. The pervasive self-immolation that results gives the movie enough edge to make up for the weak car stunts, although the bikers’ skull helmets are among the most badass the genre has to offer.

The biker-gang equivalent of Brokeback Mountain plays out like this: Horny teenage girl meets cool leather-clad boy. Boy and girl rush to the altar. Boy turns out to be much more interested in spending time with his strapping blond buddy than with his wife, leading to arguments, disappointments, and some pricey trips to the salon. The queer relationship between motor boys Reggie (Colin Campbell) and Pete (Dudley Sutton) is swaddled in inference, but it’s there — Reggie and Pete share a bed, and even Reggie’s mom is skeptical when Dot (Rita Tushingham) claims to be pregnant with Reggie’s baby. The emphasis here is on kitchen-sink drama over hot chopper action, but the film’s documentation of British biker culture post-Wild One and pre–Swinging London makes The Leather Boys a great motorcycle movie.

The first of five Stray Cat Rock movies released in 1970 and 1971, Delinquent Girl Boss stays closest to the series’ biker-movie premise. Even so, these girls are more street toughs than anything — it’s their male counterparts who rampage through Tokyo on motorcycles, partying and menacing the populace. Lady Snowblood herself, Meiko Kaji, stars as girl-gang leader Mei; Kaji’s steely-eyed action persona develops over the course of this series, and here she’s still figuring it out. Still, the elements that make these movies so captivating are all there: Cross-cultural psychedelic pastiche. Unexpectedly savage torture scenes. Mei and the girls taking a stand against racism. But what makes Delinquent GIrl Boss stand out is pop singer Akiko Wada as lone biker Ako, a queer-coded “tall woman” in lipstick and short bobbed hair who sings a forlorn musical number and gives the movie its best motorcycle action scene. She’s dreamy.

Directed by Barbara Peeters — one of a handful of women in Roger Corman’s stable of directors in the early ’70s — this lesser-known road trip–revenge hybrid stands out because it’s told from a woman’s perspective. In the opening scene, Dag (Dixie Peabody) watches helplessly as a rival gang blows her brother’s head off with a shotgun. (It’s a surprisingly gory shot, given the film’s age and budget.) This is, understandably, upsetting, and so the statuesque blonde rallies her biker buddies and sets off, as the film’s tagline infamously states, on “a hot steel hog on a roaring rampage of revenge.” The journey to get there is appealingly plotless, following Dag and pals on a picaresque trip through subcultural SoCal in search of the killer. Once she finds him, a twist — which we won’t spoil here — ups the exploitation factor in shocking, bloodstained style.

Roger Corman movies double as talent incubators in front of and behind the camera, and The Wild Angels is no exception. Peter Fonda, Bruce Dern, Diane Ladd, and Nancy Sinatra all star alongside real Hells Angels, who were recruited for the shoot with — what else? — beer and weed. The Angels’ actions are boneheaded, and the movie has an air of authenticity that only things that are ahead of the curve can have; it also features real California locations and is more honest than most about the bikers’ violent racism. Fonda delivers a generation-defining monologue, and the “biker’s funeral” smashing up a church and getting wasted while shimmying to bongos seems fun, until it isn’t. By the end of the movie, the party’s over — once again ahead of its time, as the countercultural bubble that birthed The Wild Angels wouldn’t burst for a few more years.

The first real outlaw biker movie comes from an era where squares were even more easily offended than they are now: Seventy years later, the idea of a gang terrorizing a town with pogo sticks is laughable. Still, Johnny Strabler (Marlon Brando) and his Black Rebels Motorcycle Club are leagues tougher than their coonskin-cap-clad rivals. Johnny and his beer-swilling buddies are dangerous, but local girl Kathie (Mary Murphy) talks about him like a puppy who pees on the rug. Johnny does have a wounded, sensitive soul under his brooding tough-guy exterior — another cliché that wasn’t a cliché yet when this movie was made. The Wild One is structured like a western but with no hero gunslinger to save the God-fearing small town from the marauding outlaws. That presages the cynical era to come, as does this iconic exchange: “What are you rebelling against?” “Whaddaya got?” It’s a line so good they use it twice.

Technically, She-Devils on Wheels is not a “good movie.” And yet, it’s also the greatest movie ever made. Herschell Gordon Lewis’s “ode to the violence in women” (to crib a phrase from his contemporary, Russ Meyer) operates on the sublime level of camp found in peak John Waters: The cast seems to have studied at the Tura Satana school of yell-acting, bullying each other and pushing around submissive biker boys with an aggression that’s sexual even when it isn’t explicitly sexual. The Man-Eaters’ motto is “Sex, guts, blood, and all men are mothers,” and while gang leader Queen (Betty Connell) is generous toward her sisters, one thing she won’t tolerate is a Man-Eater falling in love. Good thing this movie makes drag racing with the girls seem infinitely better than cooking dinner for some square; a rough-and-tumble bisexual leopard print Xanadu of hair-pulling, go-go boots with miniskirts, and Dolemite-style spoken word interludes.

Released relatively late in the biker-movie cycle, this Australian take on outcasts on wheels strikes an appealing balance. Stone’s outlaw bikers are convincing enough to not be cartoonish but aren’t repugnant in their piggishness. That’s because the Gravediggers, led by a cat called the Undertaker (Sandy Harbutt), are more devoted to Satan than they are to rape and murder. (Furry freak Doctor Death leads the rituals, surrounded by dudes with names like Stinky, Bad Max, 69, Stinkfinger, Septic, and Toad.) Their subterranean seaside stone bunker is awesome, as is the film’s score, which vacillates between free jazz, drone, and psych guitar. Not everyone is grooving on the Gravediggers, though, as members of the club have been dying prematurely and mysteriously. Enter Stone (Ken Shorter), an undercover cop sent to protect the bikers and root out the killer whose terrible wig belies his rebellious spirit.

The same quality that makes Hells Angels on Wheels palatable also makes it inauthentic. It goes easy on the Hells Angels, making them out to be harmless hedonists — this movie features a biker wedding, complete with Vegas honeymoon — who just want to “trip” on their motorcycles in peace. The Man won’t allow that kind of freedom, and so Angels leader Buddy (Adam Roarke) and his gang are continually hassled by cops and squares. Even new recruit Poet (Jack Nicholson) is puzzled by the club’s free-love policy, which makes his romantic entanglement with the boss’s old lady all the more complicated. Director Richard Rush would go on to make The Stunt Man, and Hells Angels on Wheels is a cut above in terms of filmmaking, acting, and stunt work. Out of all the movies on this list, this one makes the Hells Angels seem like the best time — keep an eye out for the Hunter S. Thompson analogue.

Its status as a boomer cult object has hurt Easy Rider’s reputation, at least among those who weren’t alive yet when it hit theaters in 1969. But the film is much cooler than its fans, a shaggy, low-key road movie that takes the best parts of the biker counterculture (this is an unequivocally anti-cop, pro-pot movie) and leaves behind the rest. Stars Dennis Hopper and Peter Fonda — both biker-movie veterans at this point — double as director and co-writers, respectively, with counterculture author Terry Southern contributing to the screenplay. The story strips biker narratives down to the essentials, following Wyatt (Fonda) and Billy (Hopper) as they ride across the country from Los Angeles to New Orleans, their cynicism deepening with every mile marker and hostile good ol’ boy. The filmmaking is interesting and the cast is all-around great, especially Jack Nicholson in a supporting role as a biker-curious country lawyer. Yeah, it’s pointless. But, like, so’s life, man.

In a magickal act worthy of its creator, Scorpio Rising takes experimental filmmaker and occultist Kenneth Anger’s lust for tough-guy bikers and transforms it into an epoch-shaking work of art. Filmed over several months in New York City with real Brooklyn bikers, the movie fetishizes both the men — think Tom of Finland types in tight pants filmed at crotch level — and their machines, the camera caressing chrome and leather as worshipfully as it does hairy chests and broad shoulders. It all starts off innocently enough, with cool greaser guys working on their bikes, reading comics, and watching The Wild One on TV as Bobby Vinton and Elvis Presley croon on the soundtrack. Then the film begins to whip itself into a sadomasochistic frenzy, the homoeroticism escalating alongside Christian and Nazi imagery.

Anger prostrates himself at the feet of sadistic hypermasculinity, an absolute submission to macho violence that blends sexual, political, and religious transgression. The bikers in the film were furious, the Hells Angels complained that it made them look “queer,” a Los Angeles theater manager was arrested and charged with obscenity for showing it, and the Lutheran Church and American Nazi Party both sued Anger in its wake. But Scorpio Rising was a hit in the cinephile underground, and its spell continues to enchant filmmakers: Martin Scorsese, who saw it in its buzzy initial run, has cited Anger’s use of pop music as a key influence on his own work.