To assist spend for his undergraduate training, Elias Garcia-Pelegrin experienced an strange summertime position: cruise ship magician. “I was that man who comes out at dinnertime and does random magic for you,” he states. But his most up-to-date magic gig is even additional unconventional: executing for Eurasian jays at Cambridge University’s Comparative Cognition Lab.

Birds can be more durable to fool than holidaymakers. And to do magic for the jays, he had to discover to do sleight-of-hand tricks with a live, wriggling waxworm in its place of the customary coin or ball. But executing in an aviary does have at minimum a person gain in excess of carrying out on a cruise ship: The birds aren’t anticipating to be entertained. “You never have to fear about impressing anybody, or convey to a joke,” Garcia-Pelegrin says. “So you just do the magic.”

In just the previous several years, scientists have turn into fascinated in what they can discover about animal minds by finding out what does and does not idiot them. “Magic consequences can reveal blind places in seeing and roadblocks in imagining,” claims Nicky Clayton, who heads the Cambridge lab and, with Garcia-Pelegrin and others, cowrote an overview of the science of magic in the Annual Review of Psychology.

On supporting science journalism

If you happen to be enjoying this article, take into account supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By getting a membership you are serving to to guarantee the long run of impactful tales about the discoveries and thoughts shaping our planet these days.

What we visually perceive about the environment is a merchandise of how our brains interpret what our eyes see. Individuals and other animals have developed to handle the huge quantity of visible data we’re uncovered to by prioritizing some types of info, filtering out matters that are typically much less suitable and filling in gaps with assumptions. Lots of magic outcomes exploit these cognitive shortcuts in people, and comparing how well these identical methods do the job on other species might reveal anything about how their minds function.

Clayton and her colleagues have made use of magic tricks with both of those jays and monkeys to reveal discrepancies in how these animals experience the world. Now they are hoping to expand to far more species and inspire other scientists to try out magic to explore massive questions about intricate mental capabilities and how they developed.

The science of magic

Professional magicians have usually had an intuitive grasp of human psychology, but the official scientific research of how magic performs on men and women is only two a long time outdated. It is still a market willpower, suggests psychologist Gustav Kuhn, who helped kick-start off the industry and heads the Magic Lab at the College of Plymouth in the United Kingdom. But there is now a Science of Magic Association that retains global conferences (the upcoming one particular is in Las Vegas), and in the previous two a long time or so, scientists have printed around 100 papers on magic’s outcomes on individuals, covering subject areas together with notion, consciousness, absolutely free will and beliefs.

“I believe it can give you with a new perspective on science,” Kuhn claims. Now Clayton and her colleagues are bringing that point of view to the science of animal cognition.

The inspiration to use magic tricks arrived to Clayton from Clive Wilkins, the Cambridge psychology department’s artist in home, who also comes about to be a magician. Observing Wilkins conduct sleight-of-hand tricks and stash objects in magic formula pockets reminded Clayton of a person else she is aware perfectly: the California scrub jay. Her previously work found that when scrub jays who are hiding foodstuff know they are being watched by other scrub jays, they will occur back again to re-cover the food items at the time the other birds have still left.

“A great deal of the misleading approaches that the jays use to shield their caches are items that magicians do in their performances,” Clayton claims. Jays test to obscure their steps as they conceal foods by selecting darkish areas, burying it in silent product like sand fairly than gravel, or utilizing their bodies to block a further bird’s watch. Clayton has noticed that if jays simply cannot obscure what they’re executing, they will try out to confuse onlookers by going their foods a half-dozen occasions, often feigning a cache when concealing the food items in a throat pouch.

Serendipitously, Garcia-Pelegrin was a single of Clayton’s graduate students at the time and was video game to execute tips for an avian viewers in the title of science. This associated a good deal of ready for the lab’s Eurasian jays to volunteer by traveling into a room connected to the aviary and hopping on to a perch in entrance of him.

“The papers really don’t explain to you the hrs and hours of me just sitting there by yourself, in a area in Cambridge, just chilly simply because we have no heating, just ready for a bird to show up,” he suggests. “But they do exhibit up.”

Methods for tweets

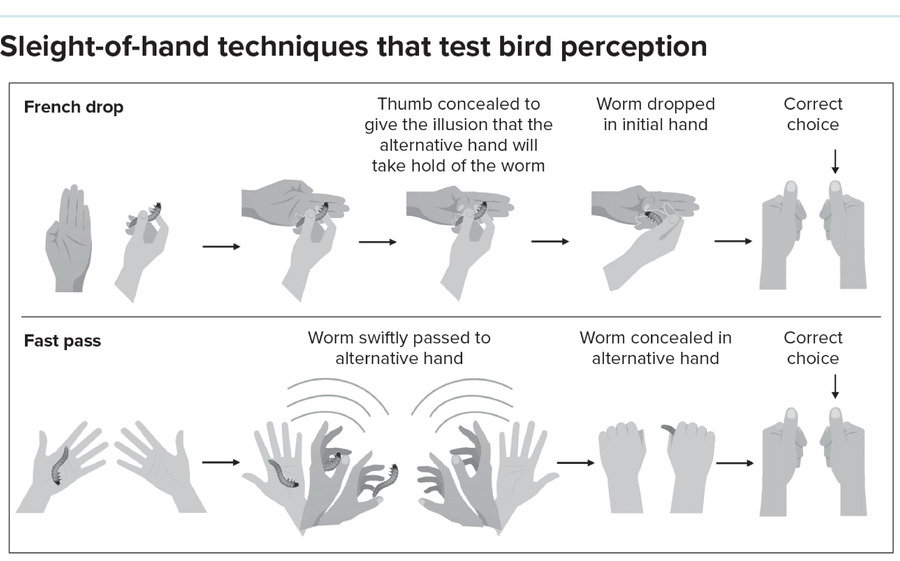

A person of the methods that Garcia-Pelegrin done for the jays is the “fast pass,” where a coin — or in this scenario a waxworm — is tossed between the magician’s fingers so promptly that the visible program of a human would pass up it entirely. When we speedily swap our gaze from 1 object to a further, our eyes go in fast jumps known as saccades, relatively than in a smooth motion that would bring about the world to blur. All through each leap, there’s a split next when we really don’t see anything at all, a momentary blindness through which a qualified magician can toss an item from one hand to yet another right in entrance of an viewers devoid of their observing it.

Birds, however, are able to see a great deal more rapidly movements than we are, and as a result don’t rely on saccades as significantly. “They are aerial beings. Staying speedy and remaining capable to properly perceive the rapidly world all over them is their specialized niche, is their specialization,” Garcia-Pelegrin states. “I would expect them to under no circumstances fall for the trick.”

Sleight-of-hand methods exploit distinct facets of human notion and cognition. By making an attempt all those exact tricks on other animals, scientists can discover one thing about how their minds differ from ours.

Knowable Magazine, tailored from E. Garcia-Pelegrin et al/AR Psychology 2024

But they did. In a video of the experiment, a jay named Homer turns his head to the side to concentration with a person eye on the worm as it sits in an open hand. As soon as Garcia-Pelegrin’s arms go laterally, Homer swiftly rotates his head to encounter forward and enjoy the relaxation of the trick with both eyes. With his beak, he chooses the hand the worm started out in, staring intently as that hand opens to reveal that it is empty. It appears to be that all through the change from monocular to binocular vision, there is a split second where by Homer’s world goes blank — a earlier unidentified blind location.

“The natural beauty right here is that this magic trick capitalized on a fully different blind spot that has zero to do with being mammal, zero to do with being human, and 100 [percent] to do with staying a chicken,” says Garcia-Pelegrin, now an animal behaviorist at the Countrywide University of Singapore.

A trick called the French drop, on the other hand, did not idiot the birds. For this trick, Garcia-Pelegrin has the back of his hand facing the bird, keeping a worm with fingers and thumb pointed up. A chook named Stuka watches as he sweeps his other hand in front of the worm as if he is grabbing it with his thumb. But Stuka chooses the authentic hand, the place the worm was secretly dropped.

At to start with the scientists were doubtful why Stuka and the other birds weren’t fooled by this trick. Some assumed it could be something about their eyesight, but Clayton had a hunch it came down to the point that birds do not have arms.

As an alternative of a blind place, the French fall relies on expectations: A person shifting their hand that way grasps the object with their thumb. Individuals in the audience never see the magician’s thumb essentially do this, they just be expecting that it does. It is a perceptual shortcut that aids us to respond quickly to the earth close to us with incomplete details. Evidently, the jays really do not have the exact expectations.

Getting raised by people, the birds are used to observing people use their thumbs to select up and maintain foodstuff, Clayton says. “But they can’t do it them selves.” She states her personal practical experience with carrying out and educating dance has offered her insight into the difficulty of hoping to embody the movement of some others who are crafted in different ways — no matter whether they only have extended arms or they have wings or flippers in its place. “For me, as a dancer, there’s a big variance concerning observing anyone do something attractive and essentially imagining how you would do it oneself.”

To test Clayton’s speculation, the experts came up with an ingenious experiment involving 3 species of monkeys with distinct thumb anatomy: capuchins with entirely opposable thumbs, squirrel monkeys with pseudo-opposable thumbs, and marmosets devoid of opposable thumbs. Garcia-Pelegrin tried the French fall on all of them and, guaranteed enough, the monkeys who are able to grasp objects with their thumbs — capuchins and squirrel monkeys — had been fooled. The marmosets responded just like the jays.

A Humboldt’s squirrel monkey is fooled by a French Drop as element of the experiment.

For Clayton, these experiments reveal something attention-grabbing about embodied cognition, the notion that the physique, and how it interacts with the natural environment, is an significant component of how minds work. The mind is not by itself in a vacuum generating feeling of what it sees, she claims. “It’s about how the whole body interprets the actions.”

Magic cups

While accomplishing magic for animals in the identify of science is a fairly new concept, methods akin to magic outcomes have been applied for many years. A person kind of experiment, borrowed from psychology scientific studies with human infants, reveals what animals realize about the globe by seeing if they are surprised by the not possible.

Babies stare lengthier at one thing that surprises them, and experts think the similar is genuine for lots of animals. Centered on staring times, experts have figured out that orangutans are bewildered when a grape goes into a container but a piece of carrot arrives out, pet dogs are perplexed if a bone magically disappears, and crows feel it is weird if a software moves on its individual.

These experiments are pretty equivalent to the traditional “cups-and-balls” magic trick where balls feel to surface and vanish under cups. Comparative psychologist Alex Schnell examined Clayton’s jays with a very similar trick when she was a postdoctoral researcher in Clayton’s lab. But alternatively of disappearing balls, the birds had been offered with magically transforming treats.

In a person variation of the trick, a bird named Jaylo sees Schnell fall a waxworm — the Belgian truffle of the jay world, Clayton states — into a single of two cups. Both of those cups are then turned upside down. What Jaylo does not know is that Schnell pre-baited the cup with a fewer fascinating piece of cheese and faked the waxworm fall employing sleight-of-hand. Jaylo topples the cup she thinks the worm is in, only to locate cheese instead. She double checks the cup for the worm and then leaves with no consuming the cheese, which is generally a flawlessly satisfactory deal with.

Animal cognition researcher Gabriella Smith has not long ago tried a comparable trick with Goffin’s cockatoos and keas — huge, gregarious parrots from New Zealand — at the Messerli Study Institute at the College of Veterinary Medication, Vienna. Making use of magic appealed to Smith due to the fact it doesn’t need education the animals and makes it possible for them to behave obviously.

“It’s a various approach to cognitive analyze, in that you are making a phase for an animal to express its expectations,” she states. “And what you are recording is the behavior in reaction to their anticipations and what comes about when you violate their expectations.”

Keas are recognised for discovering the possessions of vacationers and from time to time thieving matters (which include a GoPro digital camera, as noticed in the ensuing kea property movie). The birds in the exploration aviary are very curious and generally video game to take part in experiments, coming when their names are named and lining up to wait around their transform — though some parrots will cut the line, hurry into the screening compartment, try to steal foods and refuse to depart. “Kea are like toddlers with really sharp clamps on their face,” Smith says.

For the trick, Smith takes advantage of open up-ended picket packing containers very similar to hollow ones the birds have explored prior to. But contrary to all those boxes, these have a hidden shelf. Into the leading of the box, she drops an average address, such as a piece of apple, which lands on the hidden shelf, and then she lifts the box to reveal a tastier peanut that was secretly placed in the bottom beforehand — or vice versa.

In the case of cockatoos, Smith is wanting to see no matter if the birds flare their crests when they are astonished. With keas, she utilizes infrared thermal imaging cameras to detect changes in blood movement in the exposed skin all around their eyes.

One problem she hopes to handle with this setup is regardless of whether the animals react differently to downgraded and upgraded treats. “I was actually fascinated in getting the elation impact,” she claims — the “Oh, which is nice” emotion you get when you uncover a neglected 5-greenback bill in your pocket. There’s a dearth of get the job done on constructive thoughts in animals, Smith says, and magic might be a way to explore that.

Expanding the magic circle

For Clayton, jays seemed a normal commencing place mainly because they themselves use misleading tactics in the wild. But they are not the only kinds. Like jays, rooks have been known to act like they are caching food items when alternatively keeping it in a throat pouch. Apes are known to use their gaze to redirect interest away from one thing they don’t want other people to learn.

And male cuttlefish, which can transform the colour and texture of their pores and skin, occasionally screen a courting pattern to a woman on a person aspect of their body while hiding what they are undertaking from nearby males by disguising their other facet with woman coloration. This kind of behavior could possibly make these tricksters great candidates for remaining tricked on their own. “We have not built the experiments nonetheless, but our upcoming halt is the cuttlefish,” Clayton claims. “I assume we could use magic effects in interesting means to see what they are confused by.”

With additional experiments involving distinctive species, particularly kinds as distant as cephalopods like cuttlefish, researchers may well achieve insight into some of the greatest queries about animal minds, such as whether they are consciously aware of the past and can visualize the potential. Identifying which species have which qualities could support to piece alongside one another how these psychological capacities advanced.

“You wouldn’t automatically feel that [magic] states everything about memory or upcoming preparing,” Clayton states. “But it does — since when an item disappears, you have to have a memory of exactly where you believe it was, and you have to have an expectation of exactly where you believe it will be.”

This short article at first appeared in Knowable Magazine, an impartial journalistic endeavor from Yearly Opinions. Indicator up for the publication.

:quality(85):upscale()/2022/04/27/773/n/1922729/3ba2bcde62697e6a42ac00.30273518_.jpg)