In a spacious, all-white showroom in Glendale, the music-obsessed auction house ANALOGr has collected an intriguing bounty of rock and pop artifacts. One of Elvis Presley’s many motorcycles, a 1976 black-and-blue Harley Davidson FLH 1200 — which he kept ready for impromptu desert rides at his spread in Palm Springs — is parked inside near the front door.

Nearby is the burgundy drum kit used by Radiohead to record its 1997 breakthrough album, “OK Computer,” sitting only inches from a peppermint candy-swirled set of drums from the White Stripes. Several hot-rodded guitars played by Eddie Van Halen fill another corner, while microphones used by Nirvana and Stevie Wonder are also within reach.

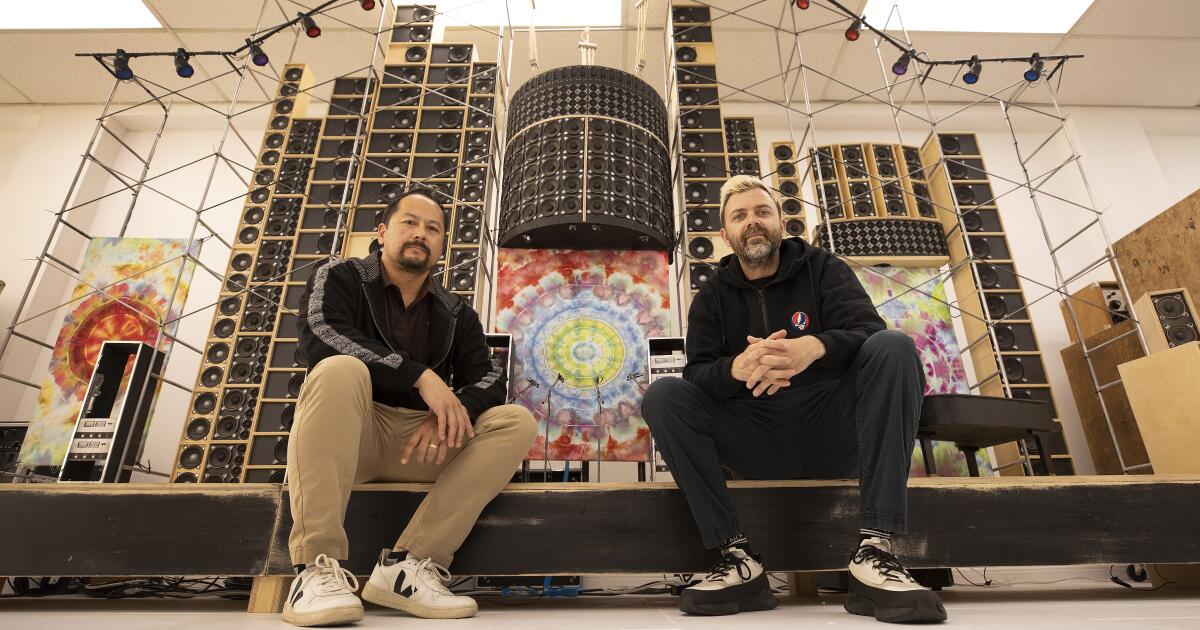

There are collectibles connected to the Beatles, the Supremes, David Bowie and the Go-Go’s, but at the moment, ANALOGr founder and Chief Executive Thomas Scriven is deep into a discussion on the Grateful Dead. The firm’s current auction, Grateful Dead 2: Rare and Curated Items, is a wide-ranging gathering of band treasures and ephemera, artwork and vintage sound equipment.

“Some of these artifacts that we’re touching, they impacted music culture, pop culture, some of the biggest moments in people’s lives,” says Scriven, 44, bearded in tie-dyed jeans, sounding like a true fan as he describes the many items spread out around him.

The auction was already in the planning stages when it was announced that the band’s latter-day offshoot, Dead & Company, would perform a high-profile residency at the Sphere in Las Vegas, where it is currently scheduled to remain through Aug. 10. ANALOGr likely will host another Dead auction later this year.

“We work exclusively with the artists to tell their story, authenticate everything, and then really work in partnership with them,” says Scriven. “We have a team of experts that we deal with on the Dead.”

ANALOGr co-founders Thomas Scriven, left, and Francis Porter with Elvis Presley’s 1976 Harley Davidson FLH 1200.

(Al Seib / For The Times)

A key ingredient in the ANALOGr marketplace is the company’s effort to tell the stories of each collectible in detail, which often means tracking down documentation and interviewing artists and experts connected to the pieces, then posting photographs and video on its website and social media. While competitors like Sotheby’s and Julien’s deal in music collectibles as part of a much broader menu of valuables, ANALOGr has found a niche with a music-only focus, giving special attention to vintage recording gear.

“They are painstakingly accurate in terms of the history,” says Butch Vig, the accomplished record producer (Nirvana, Foo Fighters, Green Day) and drummer-songwriter for Garbage. Vig will be the subject of an upcoming auction this year that will include coveted recording gear from his now-closed Smart Studios in Madison, Wis., and at least one Garbage drum set from 2005. “When Thomas was showing me all his pieces of recording gear and instruments, they have it all really well documented. That’s a big part of the company that makes them special.”

For the Grateful Dead auction, ANALOGr gathered tour itineraries, backstage crew passes, sound gear, original paintings, rare posters and one-of-a-kind mockups of tour shirts that were never put into full production. At the smaller end of the scale is a pair of NBC checks to singer-guitarists Jerry Garcia and Bob Weir from a 1992 appearance on “Late Night With David Letterman,” revealing the modest fees typically paid then for performing on a network talk show: $476.76 each.

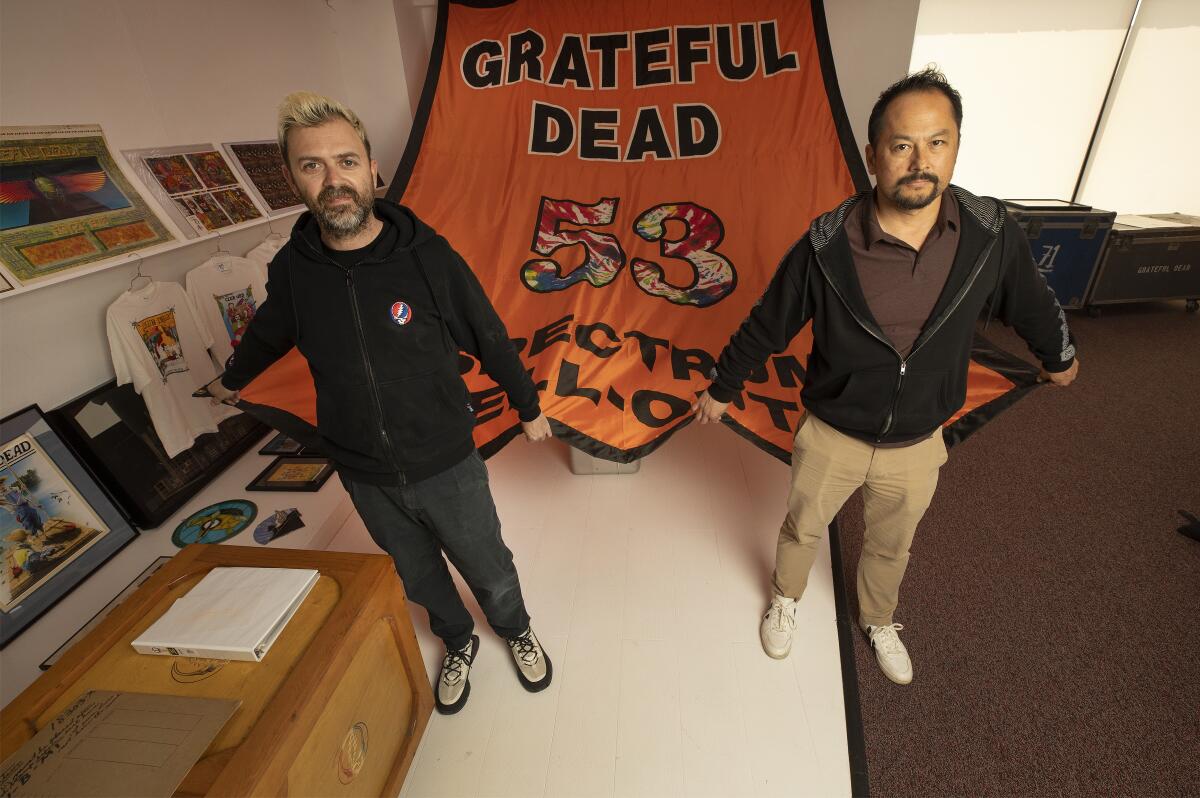

Scriven, left, and Porter pose with a Grateful Dead banner touting 53 sold-out shows at the Philadelphia Spectrum.

(Al Seib / For The Times)

The largest piece is a 10-by-14-foot orange banner marking the Dead’s 53 sold-out nights at the Philadelphia Spectrum arena; it hung from the rafters for many years beginning in the mid-1980s. Most impressively, ANALOGr has the traveling workstation from Dead production manager Robbie Taylor, and it’s an incredible time capsule of real life on the road in the 1990s — with drawers still full of guitar strings, picks, tools, batteries, Band-Aids, Advil, a hairdryer and more. Taped to one surface are the handwritten set times for the Dead’s final performance with Jerry Garcia at Chicago’s Soldier Field on July 9, 1995.

“This was the main production case for the Grateful Dead,” says Scriven, brushing his hand reverently over its polished wooden surface, inlaid with the Dead’s 13-point lightning bolt insignia. “This was basically your fix-every-problem case. There’s even rolling papers here, lighters. There’s a Polaroid camera, prescription medication, ginseng vials, all of these backstage passes throughout all the years. I haven’t seen anything like this before — ever.”

It’s a vivid example of ANALOGr’s obsessive attention to detail, and the kind of unexpected material that only emerges when digging below the surface with artists, crew and their most fanatical followers. A large number of the auction’s items originated from Club Dead, a fan-fueled company that produced bootleg shirts, hats, stickers and posters that were popular in the Dead community.

The Grateful Dead main production road case as time capsule at ANALOGr.

(Al Seib / For The Times)

Club Dead founder Tom Stack closed up his business in 1999 and ultimately became vice president for licensing and merchandise for the Dead. He never stopped collecting, and now, at 66, he’s decided to part with a lot of what he’s gathered .

“It takes a while to get in the let-go mode. When you have a collector mentality, you have to snap yourself out of it,” says Stack, who saw more than 400 Grateful Dead shows led by Garcia. “If I leave this stuff behind, my son won’t know what the hell to do, and he’ll get 10 cents on the dollar. So might as well. This stuff will bring joy to people. I’ve got awesome [stuff].”

ANALOGr started in December 2020 with a space at Mates Rehearsal Studios in North Hollywood, but as its collection and amount of merchandise tripled in size, things got crowded for everyone. “One day they’re like, ‘You gotta get outta here,’” Scriven recalls with a grin. The company landed in its current Glendale space a year ago, splitting the 8,900-square-foot building between showroom, storage and a working recording studio in back. The showroom is open by appointment only.

One item on the floor is the broken body of a Fender bass currently under investigation. The story behind the bass began when it was brought in by someone who says he was a 16-year-old extra at the 1991 music video shoot for Nirvana’s “Smells Like Teen Spirit” in Culver City. He says he was allowed to take the bass wreckage home that night. At the time, Nirvana was still a mostly unknown underground band newly signed to DGC Records, and months away from becoming one of the biggest rock acts in the world.

The problem is that another bass claiming the same rock ’n’ roll provenance currently hangs in the Hard Rock Cafe in New York, preserved in a glass case. Unless it turns out multiple Fender basses were left in pieces at the Nirvana video shoot three decades ago, one of them is fake.

A variety of guitar effects pedals at Glendale-based rock history auction house ANALOGr.

(Al Seib / For The Times)

Tracking down that history is a typical task at ANALOGr. Scriven says the company reached out first to the video’s director, Samuel Bayer, followed by the producer of the video, and then the label exec who commissioned the video — all in search of written records of the production to confirm that the kid’s name is listed among the young fans hired to appear on camera. The search has been a six-month project so far.

“We’re trying to eliminate the guesswork from anybody that would be interested in purchasing these things and looking at them long-term,” says Scriven. “We’re about the facts.”

ANALOGr has occasionally had to give collectors bad news about the authenticity of their items. “The ones that we’ve dealt with have really good batting averages, but there’s no collector out there that’s not picked up fake stuff,” says ANALOGr co-founder and Chief Operating Officer Francis Porter, 50, who brought to the operation expertise from a career in technology and filmmaking.

In some cases, the company has flown overseas to investigate and talk to the principals behind an item. “There’s a real need for it,” Porter adds. “There’s a lot of legacy artists who are getting close to having to pass on their assets. And they’re like, ‘We need to understand what we have for my kids, for my family. What’s the real value?’ If we don’t get the story now, no one will ever get the story behind this stuff.”

Clientele for collectibles tend to reflect the fan base of an artist. For an act that began in the 1960s, that fan base could be multigenerational but inevitably leans older. Studio gear tends to draw younger buyers regardless, in most cases because they plan to use it. One sale was to a van full of recording students in their late teens who drove out from Phoenix to pick up a classic Neve console.

Scriven holds a Telefunken microphone used by Stevie Wonder.

(Al Seib / For The Times)

“They all pooled their money. Their parents helped them,” Scriven recalls of the sale. “When it comes to studio gear, they’re usually professionals working in the music business and are investing in their future.”

As he talks, the sound of a grinding guitar can be heard coming from the studio space in the back, where producer-engineer Manny Nieto is surrounded by layers of eclectic recording gear. A friend and protégé of the late musician and engineer Steve Albini, Nieto is sitting with indie rock guitarist Sal Lorenzana as they record with a mic that was used by Soundgarden on the ’90s rock hit “Black Hole Sun.”

“I walk in here every day and I’m walking by Elvis’ bike. I’m walking by Pink Floyd’s microphones,” says Nieto. “It just makes you feel like there’s something important going on here. I feel like there’s little shadows and ghosts floating around here.”

One of ANALOGr’s first major clients was the widow of producer-engineer Al Schmitt, a fixture at Capitol Studios whose work stretched from Frank Sinatra and Ray Charles to Michael Jackson and Neil Young. He was the winner of 20 Grammy Awards before he died in 2021 at age 91, leaving behind many rare recording tools.

“We started working with everybody that was in Al’s life that would know anything about this stuff — ‘This is why it was Al’s favorite,’ ‘This is what he used it on,’” Scriven says. For each piece of equipment, they tracked down what records it had been used on. “The majority of the stuff based upon our work sold for massive premium, and it sold right back to Capitol Studios because they wanted to keep it.”

The competition has never been more intense for these rock and pop artifacts, Scriven notes. He calls the Hard Rock Cafe “probably the biggest memorabilia collector in the world,” now totaling 86,000 pieces at restaurants and hotels around the world (according to its website). “There’s a couple of big whales that sort of own the market right now,” he says of that competition. “But it’s also time to start looking toward the future of what new artists are doing.”

To that end, Scriven has his sights beyond the classic rock era to items connected to contemporary artists like Bon Iver and Phoebe Bridgers. Newer acts also present an opportunity for less moneyed fans to begin collecting, expanding the market beyond the usual billionaire collectors and the Hard Rock. Scriven sees that as the future of collecting.

A complete set of color-coordinated, signed and stage-played Eddie Van Halen guitars at Glendale-based rock history auction house ANALOGr.

(Al Seib / For The Times)

Until then, the big-dollar items will always draw the most attention. On the floor at ANALOGr is a black and white Fender Stratocaster that Eric Clapton played around the world in the early ’90s, at dozens of concerts from the Royal Albert Hall to Cream’s 1993 Rock and Roll Hall of Fame induction. He also played it standing beside Stevie Ray Vaughan in East Troy, Wis., hours before Vaughan was killed in a helicopter crash in 1990, and the following year during a tour of Japan with his friend George Harrison.

The guitar is paired here with a Soldano SLO-100 amplifier stack also used by Clapton at the Hall of Fame event. Together, they are currently insured for $2.5 million.

“It’s also the last guitar he used before he quit smoking,” Scriven adds, pointing to a deep cigarette burn on its neck, savoring the detail in the guitar’s history. “This is the stuff that we love. And when you love something and you dig into it like this, people can see the value. At the end of the day, it’s truth. And we can get behind the story.”