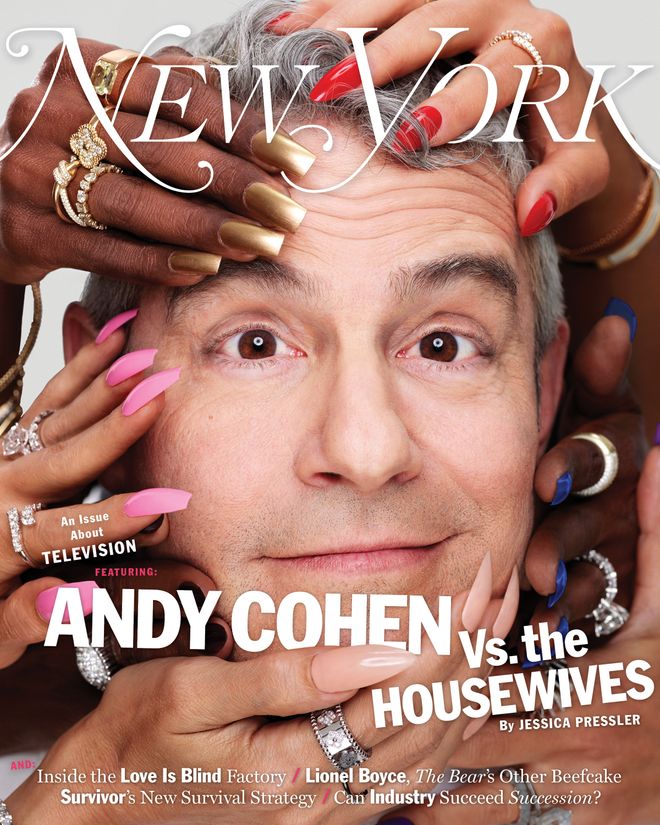

Where couples see each other for the first time.

Photo: Michael Friberg for New York Magazine

In a darkened room on a soundstage in Santa Clarita, California, seven engaged couples who have never seen each other will stand behind sliding doors on opposite sides of a long red carpet. The doors will open. They will meet for the first time, and they will react however that experience makes them react: with shock, delight, or barely disguised dismay.

This particular reveal is not going well. “Look at her face,” says Chris Coelen, the creator and executive producer of the series Love Is Blind, who watches from a large bank of screens. “She is not sold yet, in my opinion. Her face is so … She had a big sigh.” They’re filming the upcoming seventh season of Netflix’s signature dating reality show. They know they’ll have to make cuts, and this couple is obviously on the chopping block. The man, Josh, asked producers beforehand whether they could help him get a prenup, which seems to confirm their suspicion that he and his new fiancée are more excited about being on television than about being married to each other. (In order not to spoil the upcoming season, future cast members’ names have been changed.) The woman, Kayla, is the only remaining cast member who hasn’t said “I love you.” When Josh and Kayla walk toward each other, she squeals. He slings his suit jacket over her bare shoulders. Kayla tells him she swears her butt is usually bigger but she hasn’t worked out in two weeks. “You’ve got a great body,” Josh says repeatedly. Their kisses, which produce a rhythmic smacking sound, echo through the otherwise silent, cavernous soundstage.

Twenty minutes are allotted for this first meeting, and when time is up, they both walk back through their separate doors without turning around for a last look. This is a red flag for producers, who stare at the details of each reveal with the analytical intensity of commentators reviewing slo-mo sports footage. “This feels like our worst couple right now,” Coelen says. “Let’s see how the other ones play out. But it just feels fake.”

The morning’s other reveals go better. One couple may not be good for each other long term, but they’re clearly enjoying themselves; there is an almost alarming amount of giggling. Another couple, Wyatt and Harper, had an emotional connection before they could meet, but their in-person energies are out of sync. She is self-possessed; he is so overwhelmed he’s shaky and stumbling. “I find so many marriages work when it’s like the kindest men and the coldest women,” says Ally Simpson, an executive producer. Both of these reveals feel promising — even, and maybe especially, the mismatched one. Awkwardness is honest. “She needs a guy like that,” Coelen says. It’s everything the producers were hoping for: They’re adorable, a little tense, a bit unlikely as a pair but maybe actually perfect for each other.

The reveals are a crucial stage in what Love Is Blind refers to as its “experiment.” The hosts, Nick and Vanessa Lachey, begin every season by describing the pitch: Dating has gotten superficial, and this show is a chance to date without the distractions of physical looks, social media, and regular lives, an isolated meeting of minds before they must reenter the “physical world.” Cast members are “participants”; it’s a “process.” “If I was single, I would love to go through the process,” Coelen says, sounding like someone who regretfully does not qualify for an elaborate cosmetic procedure. The process is that roughly 30 single people, 15 men and 15 women, agree to date multiple other people in little rooms, called pods, that allow them to speak to whoever’s on the other side of a wall. During the ten days of filming in the pods, cast members must stay in the enclosed soundstage or inside their hotel rooms each night lest they bump into or deliberately seek out the people they’ve been dating. Their phones are taken away during production; TVs are removed from their hotel rooms. There must be no internet-connected device that would allow someone to Insta-stalk their potential mate. There are only two ways to see whom they’ve been dating: Get engaged or leave the show. After Reveals Day, producers follow a handful of engaged couples as they go on a five-day vacation, then spend four weeks back in something approaching their normal lives. Cameras follow as they get their phones back, return home and to their jobs, meet each other’s friends and families, and grapple with the person they’ve chosen to marry. In each wedding-themed finale, any couple who have made it that far stand at the altar and either do or do not say “I do.”

When the show premiered in 2020, many rolled their eyes at the absurdity of the gimmick. Then, a few seasons in, came a guilty acknowledgment of its appeal. What happens when you fall in love with someone who looks different from what you’ve envisioned? The show can capture that feeling in real time in ways that surprise both the participants and the audience. Every season, someone announces tearfully that, for them, love is blind. However, the show can also be an extended exploration of all the ways that’s often not true. Sometimes, an instant distaste destroys the relationship. Or there’s a slow-burn erosion as potential future spouses see each other in a real-life context. Occasionally, they’re shattered by the hypotheticals: They eventually meet everyone else they’ve been blindly dating in the pods. With only conversation, Jeramey chooses the practical Laura in season six; once real life enters the equation, Jeramey dumps Laura for Sarah Ann. The dramatic irony embedded in the viewing experience feels distantly related to a prank show. There’s something illicit about knowing what someone’s crush looks like before they do, in watching a participant delude themself by selecting someone destined to disappoint them and waiting for the other shoe to drop. Or maybe the delusion will stick and, actually, that’s love.

The show’s disarming qualities are also due to how it’s filmed. Love Is Blind looks and feels different from the choreographed set pieces on dating shows like The Bachelor. Coelen insists it is closer to a documentary than a reality series because producers follow the participants without attempting to control the way their stories play out. There’s no thumb on the scale for who proposes to whom. There’s not even an established format for each season: no rules about how many episodes are spent in the pods rather than back in the couples’ hometowns, how many of them have weddings, how the rhythm of proposals or reveals plays out. This looseness contributes to the sense that it’s not like all those other shows. It’s freer, more honest, more authentic.

But a number of recent legal challenges from former cast members have raised fundamental questions about how Love Is Blind works. Several open lawsuits have alleged inhumane working conditions, including claims that the cast is encouraged to drink alcohol, not given sufficient food, and imprisoned against its will. Two participants say they were pushed to keep filming by producers with partners they allege were abusive. Reporting in Business Insider and The New Yorker has characterized the show as one driven by producer manipulation. Coelen’s motivation for granting me access to the set stems from his growing frustration with the public perception of the show.

Love Is Blind’s production company, Kinetic Content, of which Coelen is the founder and CEO, has denied all the allegations. They are a continuing source of irritation for Coelen, who often brings them up unprompted. Our conversations are studded with long, off-the-record interjections. He is aggravated by what he views as an untruthful characterization of the show. From Coelen’s perspective, participants decide whether to have sex, whether to drink, whether to get into fights — that’s all on them. From another perspective, calling it a documentary can be a way to avoid liability for what happens during production.

And Love Is Blind is, of course, not a documentary. The stories may not be produced in the same way “soft-scripted” reality shows are, as Coelen puts it. But in practice, the lines are blurry; producers are neither as fully controlling as some cast members believe nor as purely hands-off as Coelen suggests. There is both coercion and freedom on Love Is Blind: Producers do not script what cast members say, but they do ask leading questions, and some cast members have said they’re encouraged to stay even if they’ve expressed a desire to leave. The interactions I witness are like a form of influence, making some paths feel easier than others, making some choices feel like rebellion and others like following the rules.

Near the end of pods filming, a cast member tells her fiancé that, earlier that day, she had been so overwhelmed she thinks she had a panic attack. Coelen shoots me a glance. “That phrase gets thrown around a lot,” he says. It’s a colloquialism, he adds. It doesn’t mean she really had a panic attack.

One of the pods where participants blind-date.

Photo: Michael Friberg for New York Magazine

Chris Coelen (left) observes the cast from the control room.

Photo: Michael Friberg for New York Magazine

In person, Coelen doesn’t suggest a high-profile founder of one of the biggest reality-show production companies in Hollywood. He’s 56, tall, and a little dorky looking. He wears transition lenses and the same outfit every day: a T-shirt and ragged jeans. He eats his cereal with water. “He just likes what he likes, and he’ll eat it every day for the rest of his life,” says his wife, Ashley Black. When she met Coelen on a blind date in the early aughts, he showed up in a messy Toyota 4Runner wearing hemp pants, two earrings in one ear, and a Che Guevara T-shirt. She’d worried he would be a “slippery, slimy” TV type and relaxed when she saw him. But Coelen is not laid back, either. He obsessively references his abhorrence of falseness. His voice grows warm when he talks about what he sees as the promise of the show: the idea that people might watch Love Is Blind and expand their understanding of humanity. One day, he sends me a link to a David Brooks column about how art can teach empathy. “It really resonated with me in terms of what we aspire to,” he says.

Coelen fell backward into reality-TV production. He was raised in Massachusetts and moved to Los Angeles to pursue journalism, getting an internship in 1990 at Fox News, where he worked for an entertainment-magazine program called Fox Entertainment News. He hated it. Too often, the show discarded quotes and ignored ideas that didn’t slot neatly into what editors had decided in advance. Everything felt fake. Part of the office, which doubled as a set, was full of phones designed to make it appear busy, but many weren’t even connected.

When the Fox show was canceled, Coelen left journalism. He started working as a talent agent in 1992. His clients were part of a growing category of people who played themselves on TV, like MTV VJs, news anchors, morning-show hosts, and early reality-show personalities such as Jessica Simpson and Ryan Seacrest. In 2006, Coelen moved into reality-show production as the U.S. head of the British production company RDF (known for shows like Wife Swap), where his job was to expand the company’s domestic business. By 2010, he had started Kinetic Content, which now makes a wide array of successful reality series, from the celebrity-adjacent game show Claim to Fame to Man vs Bear, which is based on a popular internet question about which would win in a fight. What really excited Coelen, though, was the idea of a reality series in the vein of Survivor or The Real World. The question of why people behave the way they do drew him to the genre early on. “There seemed to be an examination of society built within those shows,” he says. “I felt like the unscripted genre had gotten away from that.” If the premise were interesting enough, producers wouldn’t need to nudge cast members into having fights or hooking up with certain people. Shows about love were both high stakes and universal and became central to Kinetic’s production slate. Over the years, in addition to Love Is Blind, there has been Married at First Sight, The Spouse House, Love Without Borders, and The Ultimatum. They all poke at some aspect of the same central questions. How does attraction work? How do you know if two people are really in love?

Each of Kinetic’s relationship shows has a high-concept scheme that becomes a pressure test for the idea of commitment. On Lifetime’s Married at First Sight, a relationship expert arranges marriages, and the series follows those marriages to see whether they fall apart. Seventeen seasons in, the show is very successful; the marriages less so. “Secretly, what Married at First Sight proves is that when someone else makes a choice for you, regardless of who that person is, the fact that someone else chose it becomes the thing you’re subconsciously battling with,” Coelen says.

For Love Is Blind, his early pitch was “People want to be loved for who they are.” He played with several prototypes before landing on the pods: one with large backlit screens, plus an option with couples separated by a touchscreen where they could write messages to each other. Coelen would cast people who genuinely wanted a partner and who he felt represented a reasonable range of probable compatibility. Because Love Is Blind views eagerness to be on television to be an indicator of inauthenticity, its casting process relies heavily on recruitment rather than applications. Many of the cast members I spoke with were approached by a producer via an Instagram DM or a LinkedIn message. If someone has more than 10,000 Instagram followers, though, or has tried to be on Big Brother, Love Is Blind is probably not interested. Those are indications of someone who wants fame more than love.

Chelsea Griffin Appiah, who married her husband, Kwame, on Love Is Blind’s fourth season, now does casting work for Kinetic. “It’s challenging to find people who want this for their life,” she says. Cast members should be “good citizens,” she explains, people who are also not in the middle of a divorce and who are “mentally stable individuals.” They need to have good support systems because being on the show is hard. The casting process includes a mental-health screening in which a third-party psych team flags participants it feels would be “high risk.” “There’s a mental toll. There’s a physical toll as well,” Kwame Appiah says of a show that asks its participants to find and commit to their soul mate in a matter of weeks. “The expedited process can create a lot of confusion in our heads.”

Crew during filming.

Photo: Michael Friberg for New York Magazine

Coelen addresses the cast members during filming.

Photo: Michael Friberg for New York Magazine

Two days before filming begins on season seven, the cast meet one another for orientation in a nondescript chain-hotel ballroom in Sherman Oaks. They’re separated by sex — first the women gather, then the men. Aware that people may be coming in with a negative perception of the show, Coelen has tried to make these talks more detailed, explaining the filming schedule, how dates are assigned, and what will be expected of the cast at each stage. He doesn’t think the show needs to change, but rather that participants need a better sense of what to expect. It’s designed this way for a reason, he says, and that reason, according to him, is connection. “The experiment is not something that we’re conducting. You are the people conducting the experiment,” Coelen tells the women as they pick at Panera-catered salads. Furthermore, he adds, “this is not a TV show. We put up this machinery, but anything that happens is up to you. The pledge that I always make to people is ‘We will never, ever, ever tell you what to say; we’ll never tell you what to do, never tell you what to think, what to feel.’” Coelen has a gurulike intensity when he speaks. “Every single girl was like, ‘I feel like he was staring at me the whole time,’” says one season-seven cast member. “This man’s eye contact is insane.”

When cast members enter the pods, Coelen drops by the show’s lounges twice a day: once in the morning and then around dinnertime. These are meant to be informational sessions with advice about how to make the most of the experience. On the first day’s morning meeting, Coelen brings up the alcohol on set. “You’re all coming here with the hope of finding someone that you really fall in love with,” he tells the women. “To do that, I think you have to be comfortable. To get to know them, to open up — whatever that looks like to you. Whatever you want to wear, whatever you want to eat, whatever you want to drink, whatever you want to say. Whatever, right?” He does have a suggestion, though. “What I would recommend,” he continues, “is do not drink to — excess. Because in my experience, that’s a really bad way to connect with someone.” Coelen is, of course, aware that a reporter is watching him. (In my conversations with more than 20 cast members from previous seasons, they tell me there was no explicit suggestion they should drink but alcohol was freely available and often stocked according to cast preferences.)

The cast get conversational guides each day, asking them to discuss things like whether they want children, their relationships with their parents, how they would tackle conflicting political views. None of this is required, and some people skip them entirely. Still, these are things they should talk about, Coelen says. A cast member who doesn’t want to answer those questions may not be ready for marriage. When their dates are over, he says, the audio will simply cut out. (Despite this warning, several people on the first day end up talking to an empty room.) They should make sure to write down everyone’s names because if they forget them, the producers will not help them out and they won’t be able to put those people on their ranking sheet.

These rankings are crucial to how Love Is Blind works. For the first several nights, cast members fill out a sheet listing whom they would most like to talk to again. Coelen and Simpson enter the information into a program based on an algorithm like the one that matches doctors with residency opportunities or kidney recipients with kidneys. The program spits out date pairings for the next day based on which couples have indicated the most mutual interest. If a cast member writes that they never want to hear from any specific person again, that match is eliminated. On the first night, one woman’s sheet comes back with “Not Elliott!” written starkly across the bottom. Pairs who’ve indicated high mutual interest are more likely to be put into one of the five pods with “hero cams,” an additional set of sliding wall cameras that capture better close-ups.

The rankings — not the producers — decide who dates whom, Coelen emphasizes in the morning talks. This, he explains, is the beautiful thing about the show. “Bad for your real experience, bad for TV. Good for your experience? Good TV!” he says. Over several days of observing the production, seated at a station in the control room for hours at a time, I watch the effect of Coelen’s groundwork on the cast. Several people are doing shots by 11:30 a.m. They joke about all the food they’re being given, clearly referencing a detail in the ongoing lawsuits alleging a lack of food on set. (“You guys went to three different restaurants!” one of the men tells producers.) In their conversations with one another, many talk about their faith. “I’ve prayed more in the last two days than in the last two years,” one says. “What do you think happens when we die?” is the first question a woman asks on her first date with someone. For some, I can see the connection, or the absence of one, in real time. In between dates, crew members hustle into the pods to fluff pillows and spray everything with Febreze. This season includes two sisters, Angelina and Emma, who decide not to talk about their family connection when introducing themselves in the pods; one man, who realizes they have both described similar childhoods and cultural backgrounds, puts the pieces together. Some of the cast diverge from the talking points. One woman talks about conspiracy theories she believes, including that the moon landing was faked. Without body language, the men she’s dating can’t seem to tell whether she’s trolling them.

Season seven follows people from the Washington, D.C., area, and a few dates are quickly derailed by politics: A handsome consultant type describes himself as “a patriot,” and although he can’t see it, the woman across from him winces. “I hate Ben Shapiro, but I’ve got a good Ben Shapiro impression,” a different guy says. Throughout filming, producers pull cast members aside for one-on-one interviews. They ask questions like “Who has the sexiest voice?” and “What kind of energy does he give you?” Producers cannot force cast members to answer questions, but as production goes on, it can be easy to fall into the rhythm of answering what they’re asked. One of the sisters, Angelina, tells me about a woman who came into the lounge sobbing after a date. “One of the producers immediately wanted her to go in for an interview, and she was puffy red,” Angelina says. “She could barely form sentences, and she was like, ‘Guys, do you think I have to do this interview?’ I was like, ‘Absolutely do not do that right now.’” Angelina was clear about not doing anything she didn’t want to do. “But people would forget that sometimes,” she says.

Two days into my time on set, a woman who has had two disastrous dates in a row breaks down in the lounge. She insists the producers have done this to her. They are trying to break her, she says, weeping, to the other women, who listen sympathetically. This is a trap to create more drama. I mention it to Coelen, who hasn’t been following. He’s been staring at his laptop, working on an edit for the previous season. He doesn’t particularly care who any of these people are until they’ve made it to the proposal stage. This early in a season, he has barely learned their names.

In the control room, there’s a large whiteboard with magnetized photos of each cast member, which the production team moves around throughout filming to keep track of who’s paired up with whom and who’s deciding between more than one person. On the first day of filming, a few Netflix executives stop by to see how the season is shaping up. They put sticky notes on some of the photos to indicate their favorites. “They’re the ones I want to track,” one of them says. Producers do this too. Simpson roots for her favorites to sort themselves out, shaking her fist at the screens in frustration when she feels they’re not communicating well. It’s all wishful thinking, though — the cast choose whom they choose.

“I know I’m a main story line!” the anxious woman says to her cohort in the lounge. But she isn’t: No one is until after filming ends and the editors go back and start piecing together everything that happened. Isolated in the pods while producers observed them from a control room, it could feel as if they were being manipulated even when they were not. On Reveals Day, I glance at the whiteboard again, where the final couples are now lined up in pairs. Nearly all of the sticky-noted cast members have left.

Photo: Michael Friberg for New York Magazine

Cast members from an upcoming season on-camera.

Photo: Michael Friberg for New York Magazine

About a week into filming, the sisters, Angelina and Emma, decide it’s time to go. Angelina tells the guy she’s been dating that she really is interested in him. But she can’t imagine saying “yes” to a proposal and does not want to deal with the pressure of shooting the reveals. “The days were very long, and the cameras were a lot,” she tells me afterward. The next morning, I watch Coelen and Simpson do her exit interview as well as one for Emma and the guy she has been dating, Lucas. Someone will reach out about aftercare, Coelen tells them. “If you guys want to go see a therapist,” he starts to say. “Probably need one now,” Lucas interjects. “I love that you say that,” Coelen replies. “You spent a lot of time speaking about your feelings in a way that you don’t in the outside world. To just go cold turkey on that is weird, right? So hey — go talk to somebody! We pay for it.”

This is the kind of experience the casting team tells potential participants about the show. The production acknowledges it can be taxing, which is why it covers the cost of a therapist afterward, something Kinetic has done for cast members since Married at First Sight. When someone decides they want to leave, according to the production, they can. According to some participants, however, that is not always the case. The most public criticisms in this regard have come from Nick Thompson and Jeremy Hartwell from season two of Love Is Blind. Hartwell filed a lawsuit against Kinetic in 2022 (it was settled in May); in a podcast interview, he describes a producer reminding cast members their contracts include a $50,000 fine should they leave without producer approval. “ ‘If we catch you outside of your hotel rooms, you might be kicked off the show and you’ll have to pay the $50K,’” Hartwell recalled producers saying. Thompson got married on the show, got divorced a year later and then began to talk extensively about his experience. “I knew I was going to give my phone away. But I didn’t know I’d be put in a hotel room, isolated by myself for days at a time, unable to leave, unable to order food, unable to have access to water,” Thompson tells me. Season two was filmed in the spring of 2021 at the peak of COVID protocols, when quarantine safety procedures and food service were more of a challenge. “I get that,” Thompson says when I ask about it. “But there was nothing in the contract saying I was going to be locked in a hotel room or that you’re not going to be able to get air when you need air.”

Thompson’s season-two castmate Shake Chatterjee has a different memory of production. “There was always food available,” he says. The COVID regulations were frustrating, particularly on the romantic getaway, but, he adds, “we had a swim-out pool. It was nice.” Chatterjee has plenty of his own frustrations with Love Is Blind: He has become one of the series’ its most prominent villain figures, and he was so angry about his portrayal on the show that he refused to join Perfect Match, a Netflix meta–reality show that gathers former cast members from different series. (He did very much enjoy his experience filming a different meta-series, House of Villains, an E! show unrelated to Love Is Blind that casts reality stars from many different series. “I got to meet a different echelon of reality-TV individuals,” he says, before noting he was planning to attend Omarosa’s 50th-birthday party.) In conversations with previous cast members, their time on Love Is Blind suggested a similar set of circumstances but a kaleidoscope of responses. There’s general agreement that filming is stressful, that the isolation is challenging, and that the experience can make interactions overwhelming. For some — especially those who did get married — all of that stress is necessary to achieve the end goal. Season five’s Lydia Velez Gonzalez is still married to her husband, Milton, and she says she enjoyed the “busy schedule.”

Coelen won’t talk about the details of any of the lawsuits against the show, but he vigorously pushes back against Thompson’s and Hartwell’s broader complaints. “You are not a prisoner,” he says. “We don’t push alcohol.” The cast is provided catered meals. The $50,000 fine, he says, has never been enforced on Love Is Blind and was removed from the contract around season five. Even without enforcement, the presence of that fine could make people worry about leaving, I point out. “I’m not inside people’s heads, so I have no idea what they’re concerned about,” Coelen says.

Both Thompson and Chatterjee were featured prominently in season two. At least half of every cast, though, is made up of people who barely appear in the final edit. They don’t fall in love, or they decide to leave early, and they become brief, anonymous grist for the reality mill. One cast member from an early season tells me he spent much of his time in the pods drinking and getting too little sleep. He doesn’t blame the show for his choice to drink as much as he did, but he found the schedule destabilizing. It was optimized for cost and to protect the show’s blind-love concept but wasn’t conducive to falling in love. Cast members have the choice to stay up late into the night so they can have more pod time with someone they’re interested in. “It’s optional, but everyone did it and then call time the next morning is 7 a.m.,” he says. “I didn’t have much sleep, the meals were sporadic, and you were dating and talking for 14 hours a day. And maybe you said something two days ago you regretted and you’re worried about that. It builds up, and eventually you feel a little crazy.” They did have snacks in the lounge, he says, but he didn’t always want to eat them: “I’m not going to eat a hard-boiled egg on-camera. I’m not a psychopath.”

Eventually, it became too much and he had a panic attack while in an interview room. He’d never had one before, and he was worried it would air on TV and he would look weak. Producers persuaded him to go back to the hotel rather than immediately exit the show, and while the hotel staff was cleaning the rooms, he broke into the one next door and called his family. He learned his grandfather had COVID, and his parents used his password to log in to his email so they could contact the producers and tell them he needed to leave. At this point, he did exit the show. His mom DoorDashed him a meal while he waited in the hotel lobby for his personal effects. “It was not a great experience,” he says. I ask whether he’d ever considered a lawsuit. “I didn’t join a lawsuit because, like, I’m not a bitch,” he tells me.

“I mean, I signed up for this.”

Thompson’s and Hartwell’s claims are part of a broader movement in the reality-TV industry hoping to challenge the idea that just because you signed up for it, you have no rights throughout the process. From this perspective, reality-show participants are not volunteers; they are workers who deserve the same protections given to employees. The Love Is Blind contract classifies cast members as independent contractors who are paid up to $12,000 over six weeks. This also means it is their job to try to fall in love, which runs distinctly counter to the idea of a free-form, authentic docuseries in which enthusiastic singles go on a journey to follow their hearts. Coelen won’t speak to the work classification, but he says he doesn’t have any patience for this view. “I’m a pro-union person,” he says, but there is “lots of complexity” to this issue: “The thing people get wrong is they lump everything into a reality bucket. That is a mistaken premise.” In his opinion, a Real Housewife is more like a series regular — a reality show is her career. “If you’re a young woman from Boise who wants to be a singer and you audition for American Idol and that’s your dream, are you supposed to sign up for a reality union? Are you forced to sign up for the union?” Coelen alternates between obvious anger about the lawsuits — within moments he is telling me about how Hartwell was on set for fewer than four days — and something more like rue. People just don’t understand how the show works, he says, because they come in with preconceived ideas about the genre. “Honestly, I would have my kids do it. It is the most fucking incredible experience I have had the privilege to witness. That’s the reason to do it. It’s not a job. It’s not a career. It is an opportunity.”

Many cast members describe the pods portion of Love Is Blind as exhilarating. They talk about the intense feelings of intimacy and shared purpose of dating in a space designed to prioritize emotional connection and vulnerability over physical attraction; bonds form quickly when people leave their regular lives to experience something unusual together. But exiting the pods and reentering the outside world means confronting the sudden physical presence of a person they have only ever spoken with from behind the safety of a wall. The other lawsuits against the series concern what happens when that experience goes awry. One was brought by Tran Dang, who was cast on season five, which followed people from the Houston area. She says that during the romantic-getaway portion of filming in Mexico, producers forced her to be in close physical proximity with her fiancé, Thomas Smith, when she no longer felt safe with him. She alleges he groped and assaulted her, which she says she reported to producers the following morning. She holds Kinetic responsible for not intervening, even though, the suit claims, producers used “24-hour surveillance,” implying there were mounted cameras during filming. (Coelen says the production was never informed about the assault and that the show does not mount cameras outside the pods.)

Dang’s castmates remember her as lighthearted and sweet, a social person who liked to have fun and tended to drink a lot in pods — as many do — sometimes to excess. One recalls an incident when Dang was so intoxicated she passed out in an interview room and the set medic was called. Some of her fellow participants felt she wasn’t invested in the process. She would goof off and use someone else’s name on her dates. “She introduced herself to my husband as ‘Linda,’” says Gonzalez, one of her castmates. “She was not taking things seriously.”

Still, Dang made it far. After the pods, she continued to the romantic getaway with Smith. It quickly became clear that things weren’t going well between them. By that point, Dang had begun to tell other cast members of her reservations about Smith, who she claims kept pushing for physical intimacy despite her desire to take things slowly. During a cast party in Mexico, producers asked one of the participants to have on-camera conversations with Smith about his intimacy issues with Dang, to console him about his frustrations and to try to remind him about why he’d fallen in love with her. “Physical intimacy can be holding hands; it can be rubbing her head before bed,” the cast member suggested to him. It could be a lot of things that don’t make her feel pressured into having sex. “No, this is a nonnegotiable,” Smith responded. “I need more physically from her.” (Smith denies all of these allegations.)

By that point, Dang and Smith wouldn’t even look at each other. Dang had taken off her ring and said they’d broken up. “‘I felt like a blow-up doll in the bedroom. He’s just touching me,’” one cast member — who was close to Dang throughout the process — recalls her saying while the cameras were rolling. They asked her, “Why are you still here?” Two other participants, Jared Pierce and Taylor Rue, had already left the production. Dang told them producers wanted her to stay. “It was very obvious it was not working, but it was very obvious producers wanted it to work,” the cast member says. While the show didn’t give Dang a separate hotel room in Mexico, it provided one for her once they got back to Houston during a brief period before the cast moved into the series’ standard production-supplied apartments.

Dang left the show a week or so later. In her exit interview, the cast member says, Dang apparently communicated something about her experience that sounded an alarm to a third-party psychologist hired by Kinetic to screen and debrief the cast. Shortly after, Dang and other participants in season five were contacted by lawyers representing Kinetic asking for more details about what had taken place between Smith and Dang. The cast member suggests Dang instigated her lawsuit after Kinetic sent its own legal team to investigate on its behalf. She filed her suit in August 2022, nearly a year before the season would be released on Netflix. Dang and Smith were both completely omitted from the episodes. (Dang declined to comment through her lawyer.)

I ask Coelen what a producer’s role would be in the event a cast member reported an assault. “We would take whatever action was appropriate in line with whatever the individual participant wanted to have happened,” he says carefully. “We very pointedly don’t want people to stay in a situation that they are uncomfortable in.” He reconsiders the word choice. “Uncomfortable is the wrong word because people are going to get uncomfortable. It’s an uncomfortable situation. But it is different than if somebody says, ‘I don’t feel comfortable sleeping in the same room with a person.’ Any time somebody says that, that’s it.” That said, he continues, they have to relay this to the proper person on set. “They can’t just say it to the sound person in an offhanded moment that I have no record of,” he says. “That’s why we’re very specific about ‘Please make sure you talk to a senior-level person.’”

Dang’s castmate Renee Poche made it all the way through the final wedding episode along with her fiancé, Carter Wall. She was informed shortly before the season was released that her entire story line had been cut: most of her time in the pods, her engagement to Wall, and the aftermath in Houston, where she had grown increasingly frustrated with and frightened by what she was learning about her fiancé. According to the lawsuit, he was frequently drunk or on drugs, and he brought another woman back to the apartment building producers had rented for the couple to stay in during filming. In person, Poche was also confronting an element of Wall that the show’s blind-love premise had disguised: He is a large, physically imposing man, and Poche is petite. She claims he was volatile in ways that alarmed both Poche and the Love Is Blind producers, who she says warned her not to let Wall know where her gun was kept when they returned home to Houston.

I ask Coelen how someone like Wall could be cast despite the show’s screening process. “The way I look at it, we don’t cast the show,” he says. They “populate” the show with “a bunch of participants who we think make up a good pool within which we hope there is some compatibility.” Then the participants “cast themselves,” he says. The issue, he implies, isn’t that Kinetic had cast Wall. The issue is that Poche chose him. I point out that Kinetic does cast the initial group of participants, a process that’s meant to root out people with red flags or those who may not be able to mentally handle the pressures of being on reality television. “Listen,” he says, “it’s not an infallible process.”

Poche’s mother, Dixie, was filmed briefly for a meet-the-parents scene. “Even to me, the production crew said they knew Carter is troubled,” she recalls. “But for the sake of filming, they said, ‘Let’s just get through this.’” When she told her daughter to leave the show, she replied, “They’re going to penalize me. I have to see this through.” Poche also wanted to be on television. In text messages with Kinetic employees, she said she’d “had a blast” while filming and hoped she would be cast on Perfect Match. Love Is Blind had encouraged her down that path. Several people recall producers asking Poche to stay because she was going to be the “face of the show.” One cast member adds that they heard Coelen tell Poche this directly, too: “Chris told her that on the day of her wedding.”

“Oh my God,” Coelen says when I relay this to him. “That is …” He pauses. “I never said that about Renee. It would never be something that comes out of my mouth. I would never definitively say someone is a main character until we get into the edit and see what the stories are.” He doesn’t know why a lower-level producer would suggest that to a cast member either. “It is counter to every way the show is made,” he says.

Of course, both things can be true: Perhaps sometimes it’s suggested the process will be worth a person’s time, even if producers can never promise what will end up on the show. In Coelen’s fervor to explain what he sees as the truth of how the show works, he sometimes sounds like a cast member who has become enamored with the vision they’ve conjured of the partner on the other side of the wall. The whole of it — the lived physical experience, the compromises, the context of fame and the outside world — none of it is as real to him as the version of the show he sees in his mind.

Back in the control room on Reveals Day for season seven, Coelen is watching a couple whose path to the altar feels uncertain. The woman, Chloe, is underwhelmed by how her fiancé looks: She had pictured one kind of person, and he does not fit that image. The man, Ethan, reads like a classic reality-show guy, as though he’s perpetually on the verge of shooting finger guns at a camera operator. Chloe’s distaste, Coelen notes, is at least honest. Besides, one producer says, many people in this cast have been conscious of how they look and sound; Chloe seems less self-conscious. “We want to follow the ones we feel are genuine,” Coelen says. “We don’t want people to do stuff for TV.”

Chloe and Ethan are young, they’re appealing characters, and there’s tension between them. Although Coelen and Simpson aren’t invested in them at this point, Simpson notes that all of her young postproduction team members care more about them than anyone else. “What did you like about them?” Coelen asks a younger producer standing nearby. “I like that he gives off F-boy energy, but he has an underlayer,” she says. “He’s a cat owner.” No one seems to think the two are destined for marriage, but they’re entertaining to watch. “If there were dates going on,” the producer says, “I’d specifically tune in to theirs.” They are authentic in the sense that they’re authentically compelling to watch.

From my perspective, it seems impossible to tease apart whether Chloe has decided she would genuinely like to give Ethan a chance or whether she genuinely wants to be on this television show. With each new season, Love Is Blind becomes even more of a record of how futile it is to draw that line. “At the end, all of us went there for all the reasons,” one cast member tells me. “We want to be on TV. And we want to find love.” It’s one of the many inescapable contradictions inherent in the show and its genre at large. The experiment gets muddled by the unpredictable mixture of motivations and personalities in each new cast. The production team’s value system shapes the gut-level judgment calls of what constitutes authenticity and what reads as false. And regardless of who gets cast, who falls in love, or how producers try to sway them, as soon as the cameras turn on, the participants become a horde of anxious, horny, drunk Schrödinger’s cats: The act of watching the experiment inevitably interferes with the experiment.