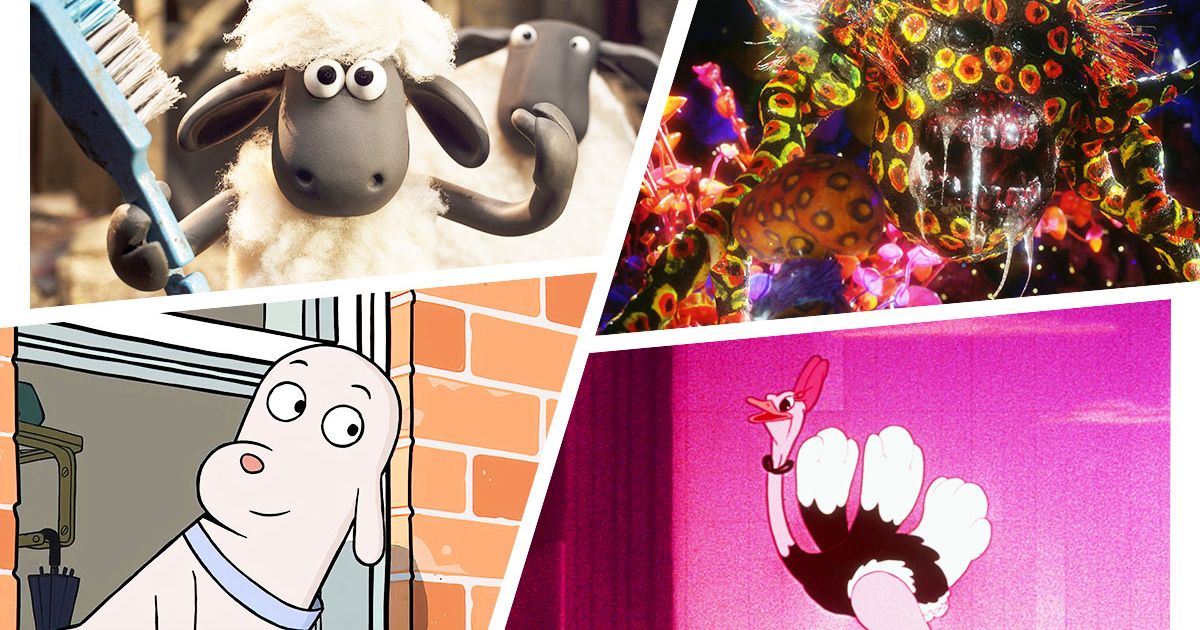

Photo-Illustration: Vulture; Photos: Everett Collection (Lionsgate, Shudder, Walt Disney, Neon)

Animation has been a part of cinema since the beginning — it’s believed that Emile Cohl’s Fantasmagorie, made in 1908, is the very first animated film. It was, as all films were then, silent. Telling stories without words became a staple of animation, with early shorts like Max Fleischer’s Out of the Inkwell series and Walt Disney’s Silly Symphonies reveling in telling stories without any dialogue.

While silent animated shorts are still commonplace, feature animation has largely left its silent roots behind. But, thankfully, there is a surprisingly impressive canon of modern animated feature films that are effectively silent. While they have synchronized sound, they explore their worlds without a word of dialogue. The latest to do so is Robot Dreams, an unexpected yet extremely deserving 2024 Oscar nominee. As the film releases this weekend, we’ve compiled a list of the finest silent animation, spanning multiple continents and regions, from big studio animation to independents (including one with a single-person creative team).

For clarity, these are the essential animated feature-length films without dialogue, so classics like Lotte Reiniger’s The Adventures of Prince Achmed, while technically silent, are not included. These films have synchronized soundtracks but have at most a few spoken words, relying almost exclusively on visuals, music, and sound effects to tell their enchanting stories.

Animation and music have a long and glorious relationship, and Walt Disney took it to new heights when merging the worlds of cartoons and classical music in 1940’s Fantasia. A series of animated vignettes, Fantasia technically does have dialogue, as live-action segments explain the animated sequences, but no dialogue is spoken when the animation takes over. Visually and aurally, it’s a spectacle through and through: “The Sorcerer’s Apprentice” is Mickey at his best and most charming, while “Night on Bald Mountain” weaves a tale of unforgettable horror. The film is long-lasting proof that box office is no reflection of a film’s quality: Fantasia performed so poorly and was so costly that it nearly tanked Disney forever. But it didn’t, and the film survives as an all-time animated classic.

Almost 60 years after the first Fantasia, Fantasia 2000 revived the merging of classical music and animation in full-blown Imax. Rather inexplicably, it reuses an entire segment from the original — “The Sorcerer’s Apprentice” — though it’s so good it’s hard to be bothered by it. Nearly an hour shorter than its predecessor, it still features some of the finest animation Disney has ever created, and while the music is undeniably great, the stories remain paramount. George Gershwin’s “Rhapsody in Blue” is brought to life with remarkable ingenuity and vibrancy thanks to the talents of animator Eric Goldberg, and “The Firebird Suite,” directed by brothers Paul and Gaëtan Brizzi, is nothing short of jaw-dropping.

An unexpected yet delightful collaboration between French musicians Daft Punk and legendary Japanese artist Leiji Matsumoto (Space Battleship Yamamoto, Galaxy Express 999) bore the ridiculously titled Interstella 5555: The 5tory of the 5ecret 5tar 5ystem. The film is technically a visual companion to the Daft Punk album Discovery, but there’s a compelling story here: An alien rock band is captured by an evil record producer who disguises them as humans and profits off their sound. Matsumoto’s distinct and vibrant visuals bring it all to life, and this is probably the loudest silent animation gets. There’s no dialogue and minimal sound effects, but there’s barely a second that Discovery isn’t blasting in all its glory.

A hilarious and madcap romp that encompasses a collage of different animation styles, Sylvain Chomet’s The Triplets of Belleville is as inventive as it is watchable. The cult hit has an addictive and ridiculous plot: French grandmother Madame Souza gets embroiled in an international plot when her cyclist grandson is kidnapped. Her dog and triplet sisters with a life on the vaudeville stage are her best hopes of bringing him home. Dialogue is nearly nonexistent, but the film thrums with a kinetic musical rhythm. The animation, full of exaggerated appendages and character design that border on the grotesque, is hypnotizing, and the story propels forward with the furious pace of a mighty cyclist. The film earned two Oscar nominations: Best Animated Feature and Best Song for the terrific “Belleville Rendez-Vous.”

Angel is a detestable man whose only real hobby is hanging around at his local bar and harassing the clientele. But one day he wakes to discover that wings have begun to grow from his back. Worse still, the wings have a mind of their own as they force Angel to do good deeds he wouldn’t have dreamed of otherwise. The outrageous Idiots & Angels is helmed by the endlessly creative Bill Plympton, whose visual style feels like an acid trip gone horribly wrong — and totally right. This is animation that employs rough pencil marks that delightfully draws attention to itself as hand-drawn. Plympton and his team’s work is so arresting, balancing the grotesque and beautiful, the chaotic and serene, that the story inevitably takes a back seat to the art. But when it’s this mesmerizing to watch, you won’t mind.

Sylvain Chomet went in a different direction both in style and content from The Triplets of Belleville in 2010’s The Illusionist. A love letter to French filmmaker Jacques Tati, the film is adapted from an unproduced script by Tati himself. It follows an elderly magician who’s struggling to find work in 1959 Paris. While traveling in Scotland, he meets a young girl, Alice, who’s enamored with his act, and the two become close friends. This tender, occasionally somber affair is full of gorgeous, precise detail. Visually, it’s exquisite, with a warm color palette and rich character designs. Its score, also by Chomet, is emotive but never overwhelming, and its lack of dialogue creates a rather gorgeous sense of longing.

A playful and adventurous spirit enchants Alê Abreu’s Boy and the World. This surprise 2013 Oscar nominee explores a young boy’s world, which is turned upside down when his father leaves their village for the city. In hopes of bringing his family back together, he leaves his home behind to try to find his father. Abreu’s film is chock-full of visual splendor, with a seemingly simple style coalescing into a kaleidoscopic explosion of color. Beneath the brightness is an intense coming-of-age story as the boy discovers a world far beyond his humble upbringing. The film is an unsubtle metaphor for the way capitalism has changed Brazil for the worse, but it’s a message that feels earnest and never preachy. There is technically dialogue in Boy and the World, but it’s Portuguese spoken backward, rendering it into Peanuts-esque gibberish.

England’s Aardan Studios has delivered stop-motion goodness for decades, and its long-running Shaun the Sheep series got the cinematic treatment with 2015’s Shaun the Sheep Movie. The story, involving a group of sheep heading into the city to bring back their farmer, takes a back seat to an endless barrage of gags. That’s a wise decision, as Shaun the Sheep is pitch-perfect family entertainment, an outstandingly funny movie that breezes through its 85-minute run time with one laugh after another. Character designs are memorable with a distinctly British charm. Watching the sheep disguise themselves as humans is a gag with a tremendous amount of mileage, and moments like the restaurant scene and doctor-dog sequence are pure joy.

Directed by Dutch animator Michaël Dudok de Wit and co-produced by Studio Ghibli, The Red Turtle is a fantastical environmental fable. Shipwrecked after a disastrous storm, a man is left to fend for himself on a remote island. The waters are full of crabs and fish, but when he discovers a giant red turtle, it will alter the course of his life completely. The film celebrates silence, operating with a sparse but effective score, allowing the lush sounds of nature to take over. This is a gorgeous and striking film with stunning animation that seamlessly blends traditional animation with CG. The backgrounds, uniquely drawn with charcoal on paper, add a remarkable dimension to the imagery. Despite it’s Ghibli credit, The Red Turtle has a distinctly European feel, but its story of love, family, and nature is universal.

A boy wakes up in the middle of nowhere with nobody in sight. All he has with him are a motorcycle and a friendly injured bird. He sets out on an adventure to get back to his family, which is no small feat, especially as a menacing giant spirit is chasing him. Latvian artist Gints Zilbalodis’s Away is an enticing visual odyssey with a unique style, recalling video games like Journey and Brothers: A Tale of Two Sons. It’s well paced, and standout sequences like the reflecting lake immerse you in this dialogue-free story. It also has possibly the shortest credit sequence in animation, as the film was made entirely by Zilbalodis.

Stop-motion and visual-effects pioneer Phil Tippett is behind some of your favorite films, including Star Wars, Robocop, Jurassic Park, and Starship Troopers. After decades in the industry and a few shorts under his belt, Tippett helmed his first feature, Mad God, in 2021, which was in production for a staggering 30 years. A masked figure, known as the Assassin, plunges further and further into a hellish landscape of one insidious creature after another. Yet beneath all the horror, there’s a remarkable sense of humanity in every creation. As a spectacle, it’s often overwhelming, as Tippett immerses you in a horrifically gruesome world bursting at the seams with fright. There isn’t anything else quite like it; if you’re into nightmare fuel, Mad God offers 83 spellbinding minutes of it.

Though Robot Dreams is director Pablo Berger’s first animated feature, it’s not his first silent film — that would be the terrific Blancanieves, a retelling of Snow White, that he made in 2012. Berger has a real knack for visual storytelling, and Robot Dreams, an adaptation of the Sarah Varon graphic novel of the same name, is one of the finest animated films of this — or any other — year. Set in 1980s New York City, the story of a dog who becomes best friends with his robot companion is a tender, uplifting exploration of friendship. It’s also a somewhat heartbreaking examination of how, sometimes, despite our best intentions, we outgrow the very friendships we long to maintain. Robot Dreams is beautiful both visually and in plotting, with characters who sear into your memory despite never saying a single word. You’ll never be able to hear Earth, Wind & Fire’s “September” the same way again — but it’s worth it.