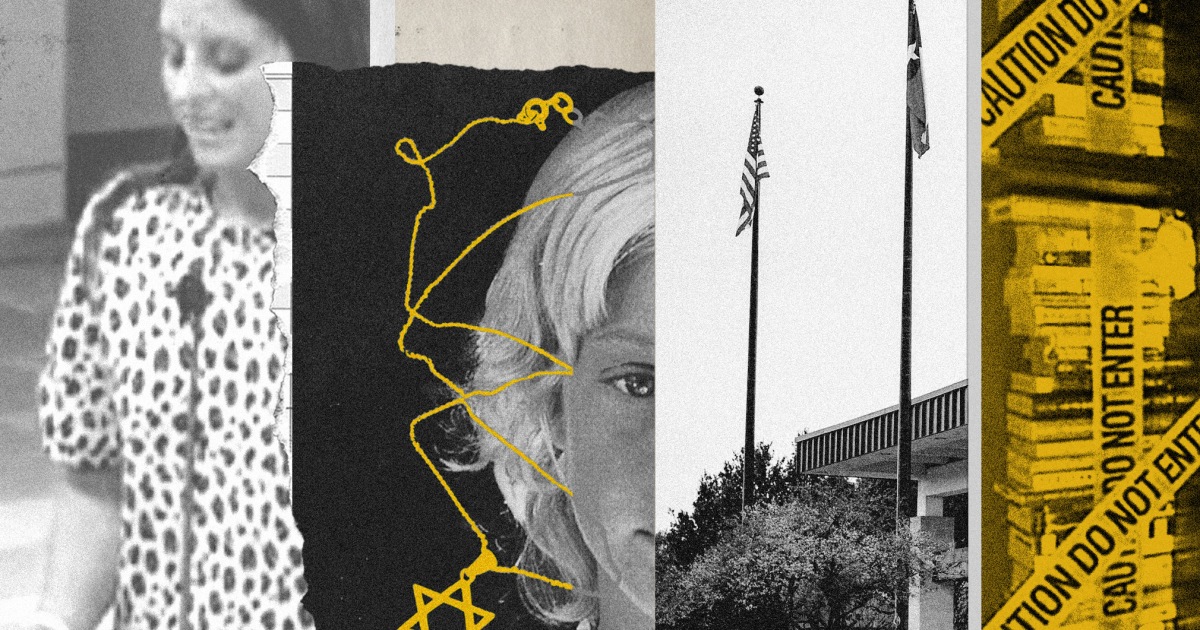

Editor’s Note: The following is adapted from “They Came for the Schools: One Town’s Fight Over Race and Identity, and the New War for America’s Classrooms,” a book by NBC News senior reporter Mike Hixenbaugh that will be published by Mariner Books on May 14.

Christina McGuirk felt as if she might throw up as she pulled up to a Dallas-area hotel in October 2021. That might have been nerves, or because the fourth grade teacher was newly pregnant; she could not say which.

McGuirk had gone back and forth all week on whether she wanted to tell her story on national television. Even with her voice and face obscured to protect her from being identifiable, she worried about the blowback if anyone found out she’d talked. Her mother, a career educator, helped her decide. “Everyone needs to know what’s happening to teachers,” she’d told her daughter. “If you don’t speak up, then who will?”

An NBC News producer let McGuirk in through a side door and led her to a private conference room where a film crew was waiting.

My colleague Antonia Hylton and I had spent a year by then reporting on the revolt against a school diversity plan in the affluent and fast-diversifying Fort Worth suburb of Southlake, Texas. The city had become a national poster child — or cautionary tale — in the new campaign to rid schools of programs, books and lessons that conservative activists were attacking under a distorted and ever-expanding definition of “critical race theory.”

That spring, candidates vehemently opposed to new diversity education programs at Southlake’s Carroll Independent School District had won seats on the school board, and in the months since, they’d begun enacting their agenda.

Now McGuirk was about to blow the whistle on what she viewed as the corrosive consequences.

Only a few days earlier a senior Carroll administrator had advised McGuirk and her colleagues to balance any classroom books depicting the horrors of the Holocaust by also providing titles written from an “opposing” perspective.

“What?!” one teacher said, incredulous.

“How do you give opposing views on the Holocaust?” said another.

“Believe me,” the administrator responded through the shocked commotion. “That’s come up.”

Another teacher wondered aloud if she would have to pull down the children’s classic “Number the Stars” by Lois Lowry, or other historical novels that tell the story of the Holocaust from the perspective of its victims. Was she supposed to find a story told from the perspective of Nazis? Or one from the point of view of Holocaust deniers? Should they also balance accounts about the horrors of slavery by adding books written from the perspective of white supremacists?

The administrator’s instruction — which had been secretly recorded and provided to NBC News — was meant to help teachers comply with a new Texas law that required schools to present both sides of any “currently controversial” subject. But to McGuirk, 28 at the time, the Holocaust guidance was the latest and most disturbing sign of the far-right’s tightening grip on her school district — and a warning of what could be coming to schools across the country.

Her fears would prove warranted. A recent nationwide survey of teachers revealed the toll exacted by three years of partisan attacks on public education. Two-thirds of U.S. teachers told the Rand Corp. that they had limited discussions of political and social issues — including racism and LGBTQ topics — in their classrooms. Many said they self-censored because they feared losing their teaching licenses, or because they did not trust that administrators would defend them from parent complaints.

In this climate, some teachers have left education entirely.

McGuirk, who’d gotten into teaching as a way of living out her Christian faith, by showing kindness and compassion to children, had decided to stay and fight for what she believed was right.

Her hands were shaking, but once in the interview chair that afternoon in October 2021, she felt a rush of confidence that she was making the right choice. Another teacher, one of at least six Carroll educators who spoke to reporters that week to voice concerns, was seated next to her.

“The district says that they have not told teachers to ban books,” Hylton, my colleague, said in an exchange that would make it into a piece that aired that week on “NBC Nightly News.” “What are you seeing?”

“That’s a lie,” McGuirk responded sharply. “It is a flat-out lie.”

Later in the interview, in a moment that didn’t make it into the final cut, McGuirk explained why she and other teachers were willing to put their jobs on the line to bring this situation to light.

“We felt like no one was going to listen,” she said, “until a teacher spoke up.”

But in the end, only one person suffered formal consequences because of the Southlake Holocaust fiasco: McGuirk.

On the afternoon of Oct. 14, Hylton and I published an article headlined “Southlake school leader tells teachers to balance Holocaust books with ‘opposing’ views.” That evening, McGuirk’s interview aired on “Nightly News.” Very quickly, the story went international.

The words “Holocaust” and “Southlake” became the No. 1 trending topic on Twitter, and to some the story became a symbol of the overreach of the conservative movement against diversity, equity and inclusion. The story got picked up by nearly every major news outlet in the country. The Auschwitz Memorial responded by posting tips for teaching about the Holocaust on social media and tagged the Carroll district’s Twitter account.

Jewish authors and descendants of Holocaust survivors went on cable news and wrote scathing editorials. Lowry, the “Number the Stars” author, appeared on CNN the next morning, telling anchor John Berman that she’d initially chuckled when she heard the audio from the teacher training on NBC News. “It seemed silly,” Lowry said. “But the more I thought about it, it wasn’t laughable. It was ignorant. And ignorance so easily morphs into evil.”

Carroll’s school superintendent, Lane Ledbetter, apologized for the comments by one of his administrators in a statement and acknowledged that “there are not two sides of the Holocaust.”

At a tense school board meeting the next week, residents came forward to express their outrage. More than 50 people addressed the board, many of them demanding that the district take steps to repair its reputation. Teachers teared up as they described feeling unsupported and under attack. For some, the episode had ripped open old wounds. A Jewish former student gave testimony about antisemitic bullying that he’d endured at Carroll in the early 2000s.

One of the final speakers of the night approached the microphone and drew in a deep breath. In a shaky voice, she opened by explaining that she’d known ever since she was a little girl that she wanted to be a teacher.

“Teaching is what I know I have been called to do,” McGuirk said as tears formed in her eyes, speaking out publicly after having secretly done so on national television. “I love your kids, and they are my ‘why?’ My goal as their teacher is to make sure I provide an environment that allows them to learn, grow and have fun daily — to provide a space where all students feel safe. And I wish some of you made me feel safe in return.”

When McGuirk returned to her seat, she glanced at her phone.

While she was speaking, she’d received a text from a conservative parent who’d once had a child in her class. The woman also had spoken during public comments that night and was seated nearby.

The parent’s message sent a rush of panic through McGuirk: “I am so disappointed you went to NBC.”

The fourth grade teacher took another deep breath, then closed the text without responding. That mom was probably just guessing. There’s no way, McGuirk reassured herself, that she had evidence to back up her accusation.

In the end, after the media firestorm died down, the controversy over the Holocaust remarks inspired just one concrete policy change in Southlake, but not one the whistleblower teachers had hoped for. The school board voted that winter to prohibit employees from secretly recording district business. The administrator’s instruction wasn’t the problem in need of solving, it seemed; the publication of it was.

For the rest of that school year, survival became McGuirk’s mantra. She’d seen how attacks by newly empowered activists had upended other teachers’ lives and careers. McGuirk, who was due to give birth the following summer, just needed to keep her head down. To avoid conflict, like so many other teachers nationally, she removed every book from her classroom library and avoided discussing subjects that might upset conservatives — becoming, in some ways, a shell of the teacher she’d hoped to be.

Then, in April 2022, as the school year was winding down, she received an email from a mother and activist who’d been among the most outspoken opponents of diversity, equity and inclusion programs at Carroll. McGuirk’s heart was racing as she opened the email. The parent had copied senior district administrators and a pair of like-minded school board members. “Did you know April is contract negotiation month?!?” the parent wrote, and then shared a link to an audio file.

When McGuirk clicked play on the file, she immediately recognized it as a recording of her anonymous interview with “NBC Nightly News” from the previous fall. Someone, it seems, had managed to undo the complex digital distortion that our audio engineers had applied to mask her voice and the voice of another Carroll teacher who’d spoken to us.

“Oh my God,” McGuirk thought as she played the clip again, recognizing her own voice with near-complete clarity. The audio still sounded slightly distorted, making clear this wasn’t a leak of our raw footage, but instead a feat of digital wizardry.

Exactly how this was possible, and who did it, remains a mystery. Audio experts said it likely would have required sophisticated software and someone with advanced technical knowledge to reverse the distortion techniques used by major broadcast outlets to mask the voices of confidential sources. The audio file linked in the email also included the unscrambled voice of a third Carroll educator who’d spoken anonymously to CNN in a separate interview about the Holocaust controversy.

Based on the other names copied on the parent’s email, it did not appear she or other conservative activists had successfully identified the two other teachers who’d given television interviews. In McGuirk’s case, they’d compared the unscrambled audio of her October interview with a recording of her public school board comments.

“I never in a million years would have imagined people would go to such extreme lengths to punish a teacher,” McGuirk said.

Her initial plan was to ignore the email and hope that school officials would do the same. She hadn’t done anything wrong, she reminded herself. There was no rule in her contract that said teachers couldn’t talk to reporters. But at school the next morning, McGuirk received another email that made her start to panic. This one was from Ledbetter’s assistant; the Carroll superintendent wanted McGuirk to meet him at his office after school that afternoon.

McGuirk’s principal was stunned; normally staffing issues were handled at the campus level. “You have to be strong,” the administrator encouraged her. But McGuirk, nearly seven months pregnant, wasn’t feeling very strong as she arrived at Carroll’s central administrative offices that afternoon, accompanied by a lawyer from a state teachers union.

“How’s your pregnancy going?” she recalled one of Ledbetter’s deputies asking, making small talk as McGuirk sat down across from them.

“Not good,” McGuirk replied. “I’m stressed out.”

Ledbetter, who didn’t respond to a request for comment, cut to the chase, McGuirk said. He told her that the school board — now fully in the control of conservative members who promised to purge the district of “woke” books and lessons — had voted the night before to approve annual contracts for all the district’s teachers. But the members had set hers aside for special consideration.

Before the board voted on whether to bring McGuirk back for the following school year, there was one question that needed to be answered, Ledbetter said. Then he set his phone on the table and hit play on the same audio file that the parent activist had emailed. McGuirk’s lawyer had advised her not to show emotion during the meeting, but as she sat across from her superintendent and listened to the recording of herself criticizing his administration on national television, she began to cry.

After the audio file finished playing, McGuirk says Ledbetter asked, “Are you telling me this isn’t your voice?” Before she could answer, the union lawyer interjected.

“I have advised her not to answer that question.”

“This is your chance,” Ledbetter said to McGuirk. “Is this your voice?” She took her lawyer’s advice and declined to answer, although the tears streaming down her cheeks must have signaled the truth. “OK,” Ledbetter responded. “That’s all we needed to know.” He said that he would pass this information along to the school board and that they would decide what to do with her contract at the next meeting.

But as she walked out of the superintendent’s office that afternoon, feeling depressed and defeated, McGuirk’s future at Carroll had already been decided — by her.

The majority in town no longer wanted people like her teaching their children, she told herself, polluting their minds with what she considered irrefutable truths. Yes, racism exists. No, there is nothing to debate about the horrors of the Holocaust. Yes, some kids have two dads. It’s OK to be different. She still believed every child deserved to learn those lessons. But with her own baby on the way, she was too tired to keep fighting.

Four years after accepting what she thought was her dream job teaching fourth grade in the elite suburb of Southlake, McGuirk resigned.

The only question now was whether she would ever teach again.