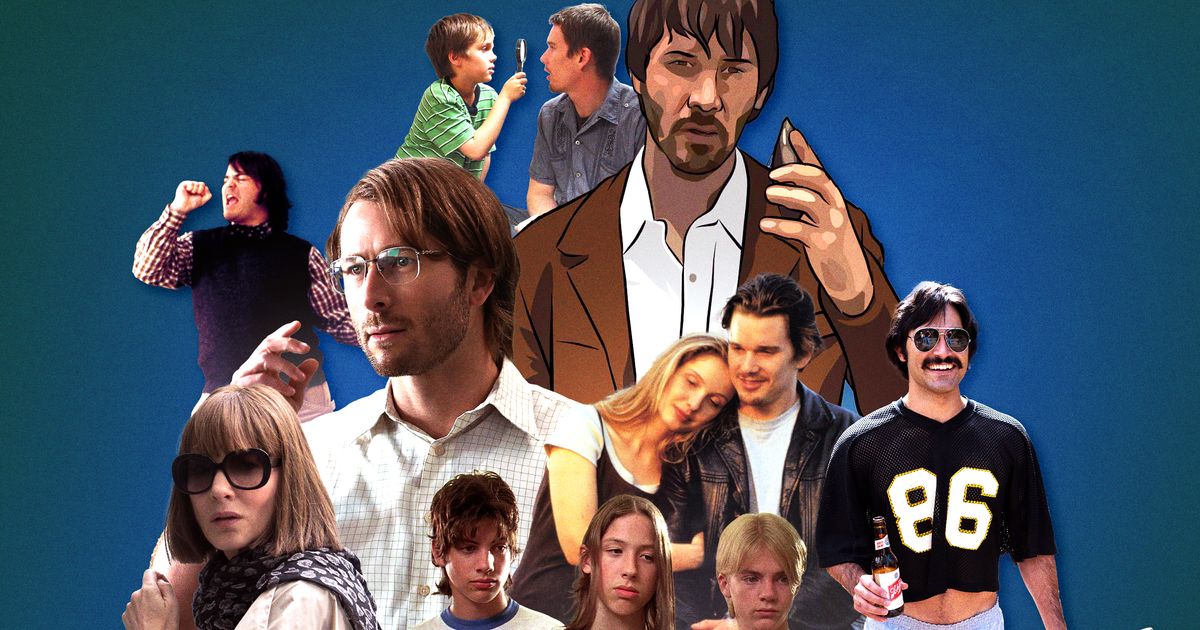

Photo-Illustration: Vulture; Photos: FilmDistrict, Focus Features, Lionsgate, MGM, New Line Cinema, THINKFilm, Universal Pictures, Warner Bros Pictures

This article was originally published on July 21, 2023. We’ve updated it to include Ryan Gosling’s latest movie, The Fall Guy.

For a few years there, Ryan Gosling’s status as the internet’s No. 1 boyfriend threatened to overshadow his presence as an actor. The stillness, the composure, the sly self-awareness, and the bursts of rancor that he’s used to bounce between psychological thrillers and romantic dramas, buddy comedies and big-budget sci-fi sequels, were being flattened by fans into a cute (but limiting) “Hey girl” memeification. Yes, the Canadian former Mickey Mouse Clubber is handsome and charming, and there’s nothing wrong in pointing that out. (We are not immune; we’re even going to talk about his looks in this list!) But over more than 20 years onscreen, he’s also cultivated a fascinating malleability that made him a worthy agonized heir to Harrison Ford in Blade Runner 2049, the only good white man to listen to jazz in La La Land, and a perfect foil to an eye-rolling Russell Crowe in The Nice Guys. He may just be Ken, but he’s not just Ken, you know?

Gosling’s career can be roughly chopped into phases: the tortured young men of The Believer and Stay, the singular and silent heroes of his partnership with Nicolas Winding Refn, the wounded lovers of his work with Derek Cianfrance, the cerebral and heartbroken guy in Song to Song and First Man. Across genres, his roles share a kind of idealistic yearning to be seen and to be known that Gosling conveys with those soft eyes and a tired half-smile. He’s been nominated for two Academy Awards for Best Actor — although, in traditional Oscars fashion, not exactly for his best roles — but he’s also had some duds (a very kind way to describe the existential headache of The Gray Man). We discuss those extremes in this complete ranking of Gosling’s theatrically released movie roles, meaning his work in TV isn’t included. Our apologies to the legions of Frankenstein and Me fans, but here are our assessments of Gosling’s other performances, listed from worst to best.

Oof. On paper, Gosling’s turn as a CIA operative named Six who is entrusted with protecting a tween girl from an unhinged assassin should be, if not amazing, at least watchable. There’s connective tissue between his character here and his PI Holland March, responsible for a headstrong daughter, in The Nice Guys, and to be fair, Gosling’s chemistry with Julia Butters (the scene-stealer from Once Upon a Time … in Hollywood) is solid. But outside of their relationship, Six is so glib and so slick that Gosling is almost doing a Ryan Reynolds impression, and the movie’s action — which could show off another element of Gosling’s physicality — is so choppily edited that it’s impossible to get a sense of his bodily grace. He’s not the right fit, and overall, the Russo brothers’ movie is not a good time.

Terrence Malick has made many gorgeously layered, distinctly evocative films, but Song to Song isn’t one of them. This narratively thin work almost feels like a Malick caricature, what with all the endless voice-over, shots of men kneeling apologetically before women, and romantic melodrama between characters played by Rooney Mara, Michael Fassbender, Natalie Portman, and Gosling. As BV, the musician in love with Mara’s Faye, who’s cheating on him with Fassbender’s record producer Cook, Gosling has barely anything to do. He gets in some little moments that seem unscripted — a giant smile watching a bird select paper slips from a box, a believably furrowed brow while working on an oil rig — but he has the least dialogue out of all four main characters, and the movie’s too abstract to make any meaningful use of him. Plus, Malick denies us a Dead Man’s Bones reunion, a majorly missed opportunity to reignite Gosling’s music career of singing silly, spooky songs like “My Body’s a Zombie for You.”

Gosling’s roles tend to organize themselves into slightly connected pairs, and this indie movie starring Gosling as a high-school football player struggling to figure out his future comes a couple years after Gosling starred in another high-school-football movie, Remember the Titans. In The Slaughter Rule, athlete Gosling faces off against coach David Morse in an overly plotted story about football as masculine expression, and that masculine expression as a stand-in for masculine desire. Morse is electric as the closeted, somewhat cruel bully Gideon to Gosling’s trying-to-please Roy, and The Slaughter Rule is beautifully shot, with directors Alex Smith and Andrew J. Smith taking full advantage of their Montana location. The pacing is uneven, though, and sometimes Gosling’s fragility is broad when it needs to be precise. It’s an acceptable early performance, but it also feels young in Gosling’s understanding of himself as an actor.

Gosling cycled through a few “disturbed young man capable of a shocking act” roles early in his career, with The Believer, The United States of Leland, and Stay all drawing from that well. Of those three, The United States of Leland is probably his flattest attempt. As Leland, a teen who kills his ex-girlfriend’s developmentally disabled brother, Gosling mostly stays blank and vacant; his unwavering reticence is required by Matthew Ryan Hoge’s script, which relies on a final reveal to justify its existence. It’s not entirely Gosling’s fault that the character is more irritating than compelling, and he holds his own in scenes with Don Cheadle as a teacher who considers writing about Leland. (A post–Twin Peaks Sherilyn Fenn and young Michael Peña are absolute casting coups.) But Leland is ultimately too clichéd for Gosling to do much with.

It’s impossible to tell exactly when Gosling started doing his De Niro–esque New York accent; its slow creep into his voice has been going on for a while. But All Good Things is probably when it’s felt most appropriate, since Gosling plays a Manhattan real-estate heir (and Robert Durst analog) accused of killing his wife (Kirsten Dunst). He nails the voice, and he nails the movie’s big emotional asks — a scene in therapy where he screams his guts out, a tear when confronted by his father about his poor business skills. But the movie never quite grows out from its ripped-from-the-headlines roots, and the script’s character-development gaps in how it alters Gosling’s David from a peculiar but besotted husband into a hair-triggered murderer make his performance feel a little overstretched, too.

David Benioff wrote 25th Hour (great), Troy (good), and then Stay, this nearly impenetrable psychological thriller that plays out like The Machinist through a David Lynch filter. Championed by Roger Ebert but ultimately a box-office flop, Stay’s plotting is far too tedious and the characters played by Ewan McGregor and Naomi Watts too vague for any of it to gel. But then there’s the scene in which Gosling’s character weeps in the middle of a strip club while women dance to Massive Attack’s “Angel” — it’s a real “What’s happening here, and do I care?” viewing experience. Still, Gosling is serviceable as a young man who hears voices, puts out cigarettes on his arm, and tells his psychiatrist (McGregor) that he’s going to kill himself. It’s not nearly as raw or visceral a performance as his work four years earlier as a live-wire neo-Nazi in The Believer, but that’s because the movie surrounding him isn’t as good.

Look, we are judging performances here, not the movies themselves, okay? Gangster Squad had the ugly uncanny-valley aesthetic of a Sin City knockoff, a too-big ensemble, and overly slow-mo-dependent action scenes. That all unfortunately overshadows the palpable affection Gosling and Emma Stone have in their second of three movie romances, and even Gosling’s playboy charisma gets dulled a bit. The actor has played men with strict moral codes and ruthless tactics many times throughout his career, and this just isn’t the best version of that. But he stands out for his dry line deliveries (“Well, you gotta die someday” is wonderfully blasé) and the genuinely fatigued affect he brings to his World War II veteran and cop, and, hey, he looks great. There’s a moment where his otherwise lacquered hair gets sweaty and falls over his forehead as he points a shotgun at a baddie, and it’s very satisfying!

Emotionally manipulative, arguably inaccurate, and thoroughly pleasant, Remember the Titans is one of the better entries in the “civil-rights history through sports movies” cinematic trend, and that’s because Denzel Washington is Denzel Washington–ing all over the place. He’s got gravitas, he’s giving tough love. And while Gosling isn’t in this much — he’s really just a supporting player to Ryan Hurst and Wood Harris, and Donald Faison and Ethan Suplee were both more recognizable young actors at the time — he’s goofy and open in a way that reflects his Mickey Mouse Club training and lays the groundwork for his later singing and dancing in La La Land and Barbie. The locker-room scene in which he sings along to “Ain’t No Mountain High Enough” is almost cringingly earnest, but Gosling gives himself over to it completely, and that lack of artifice is a nice reminder of the looseness he’s capable of.

It is a cinematic rite of passage for up-and-coming white actors to play lawyers or law students, and Gosling joined the ranks of Tom Cruise, Julia Roberts, and Matt Damon with Fracture. It’s a fairly by-the-numbers legal thriller, with Gosling’s district attorney Beachum prosecuting Anthony Hopkins’s engineer Crawford for attempted murder and getting caught up in the man’s mind games and manipulation. Gosling does well in this role, though, because he’s an engaged scene partner with Hopkins (watch how absorbed and frustrated he is when they’re in the courtroom together) and because he excels at playing obsessive figures driven by a single-minded purpose, which Beachum becomes when Crawford is acquitted. Gosling hasn’t played that many good-guy law-enforcement roles where the character he’s embodying isn’t swayed into ruthlessness or recklessness, and Fracture remains something of an outlier in his filmography. It’s familiarly plotted, sure, but efficiently acted.

Yes, yes, the Photoshopped abs. We’re all aware of the most memorable line from Dan Fogelman’s script. Kudos to Gosling, though, for making the skinny-suit-wearing womanizer Jacob more than just an exceptionally sculpted torso. He’s scathing in his scenes with Steve Carell as hopeless near-divorcé Cal, all exasperated sighs, mirthful giggles, and disgusted body language; his comedic timing is on point. There’s also the sense, as the years have passed, that this role is the nexus for a number of quirks that Gosling would bring to his later roles, and even his public persona. His repulsed, step-back-and-stare reaction to Cal’s velcro wallet is a precursor to his exaggerated enmity toward Simu Liu’s other Ken in Barbie; he covers a laugh with his left hand in the Crazy, Stupid, Love trailer and onstage at the Oscars. Gosling is clearly having fun, and while a solid half of this movie is a drag, he’s at least entertaining himself (and us).

Nicolas Winding Refn’s second collaboration with Gosling could have been goofy as hell. To be honest, it sort of is: all Freudian mommy issues, mythological meandering, and the most atmospheric bisexual lighting you’ve ever seen. But it’s also a testament to Gosling’s star power that he can anchor a film this unbelievably weird and brutal and keep us mesmerized throughout. The long sequence in which Gosling, playing American expat and Bangkok crime boss Julian, unbuttons his cuffs, pushes up his sleeves, circles around Thai police lieutenant Chang (Vithaya Pansringarm), and challenges him to a brawl with a direct-to-camera “Wanna fight?” might be the hardest the actor has ever looked. The fact that he then gets his ass thoroughly kicked by Chang embodies not just Refn’s grim sense of humor, but also Gosling’s willingness to get as dirty and demeaned as a role requires. And that’s even before Julian cuts open his mother’s corpse and shoves his hand inside of it to feel close to her for the first time in his life! What other actor could make that moment pitiable, even understandable?

“You exude something. You draw people in,” Paul Giamatti’s Tom says to Gosling’s Stephen in The Ides of March, George Clooney’s political drama, and duh, he’s right. Released during Obama’s first term, this movie’s cynicism didn’t go over super-well; the film’s negative reviews were particularly hard on the idea that maybe Democrats and Republicans can both be bad. That realization, though, is key to Stephen’s curdling idealism in the film, a moral collapse that Gosling gives urgency and despondency. Gosling sells both sides of the character. First, he’s a political-operative hotshot totally sure of his own supremacy and fully confident that sleeping with a college student on the campaign trail won’t affect his career at all; how often Gosling looks at Evan Rachel Wood’s lips when she’s talking is, frankly, very hot, and he deftly conveys Stephen’s easy professional and personal confidence. His turn into villainy is trickier, yet Gosling hardens his voice and his gaze and successfully spars with the murderer’s row of Giamatti, Clooney, and Philip Seymour Hoffman. The film’s bookended auditorium scenes, and how they center Gosling’s transformed character, are a thoughtful touch.

Gosling is fantastic at being irritated. His voice gets clipped, his face gets tight, and his inflections go to unpredictable places, like the staccato edge he gives to “money” as Deutsche Bank salesman Jared Vennett in Adam McKay’s film. A simplified read of this performance would be to say it’s Gosling cosplaying as Alec Baldwin in Glengarry Glen Ross, and sure, he’s doing a fast-talking finance-bro thing. Gosling lightens it up with moments of dorkiness, though — a juvenile fist pump in the gym after a major sale, a stanky face when he shows off his $47 million check at the end of the film — that bring the performance closest to the point The Big Short makes about the 2007 housing-market crash and how it was created by people with too much money and privilege and too little oversight or consequence. Every member of this ensemble (Steve Carell, Brad Pitt, Christian Bale) does their part, but Gosling’s tone is most right for McKay’s specific style of satire.

Gosling has been an A-list movie star for many, many years, even if he’s only felt truly inescapable in the year after Barbie: releasing a music video with Mark Ronson; performing a delightfully committed, impressively elaborate version of “I’m Just Ken” at the 96th Academy Awards; driving Heidi Gardner to lose her mind during Saturday Night Live’s instantly iconic Beavis and Butt-head sketch and then reprising the role at The Fall Guy’s Los Angeles premiere. All of this is to say, the man is a good sport, and his work in The Fall Guy as stuntman Colt Seavers reflects that amiability. Colt’s just a guy who wants to do his dream job with his dream girl (Emily Blunt) by his side, and Gosling is immensely likable as someone who willingly goes on a bizarre chase to retrieve a missing A-list actor because he simply wants to go back to doing the stuntwork he loves so much. Admittedly, there’s not a lot that’s new to Gosling’s performance — he’s mixing together the high-pitched mania of The Nice Guys, the besotted adoration of Crazy, Stupid, Love, and the sarcastic edge of The Ides of March — but it’s a perfectly controlled calibration of all the stuff he does so well. And as the third time he’s playing a stuntman (after Drive and The Place Beyond the Pines), David Leitch’s film marks a new height in Gosling’s awareness of his own physicality, his ability to throw and take a punch and command attention in a scene where a million things are moving around him. He deserves a Fall Guy–appropriate thumb’s up.

Remember when we used to make fun movies about little freaks? Murder by Numbers is an entertainingly nasty thriller about two high-schoolers, popular Richard (Gosling) and introverted Justin (Michael Pitt), who plan the perfect murder and frame a local drug dealer for it. When Sandra Bullock’s detective is assigned the case, she immediately suspects Richard, whose entitled attitude reminds her of an abusive man from her past. Gosling’s a proper asshole, a know-it-all brat with pique and smarm to spare; his layers of duplicity here will make you long for him to try on another fully villainous role. In his best moments with Pitt, they embody a teen-drama version of Matt Damon and Jude Law’s relationship in The Talented Mr. Ripley, and I know that’s very high praise. It’s also deserved.

La La Land has its detractors, if you see Damien Chazelle’s film as one that exists solely to portray Gosling’s pianist Seb saving jazz. What La La Land is more about, though, is effort: the effort required to chase your dream and to fall in love, to further that dream and to maintain that love. Is all that effort worth it if you achieve one form of success, but not the other? Chazelle forces us to decide in the film’s devastating final moments. And because Gosling is so adept at conveying the process of trying before then, he makes Seb’s journey look more straightforward than it really is. Think of the exhaustion with which he sings “City of Stars,” a love song to a place he’s realized might never love him back. As he walks on that pier, it’s with a weary forlornness that contrasts well with how gently he duets with Emma Stone; here, maybe, is someone who would make this time fuller, more vivid, more real. The imperceptible smile he gives Stone’s Mia, years after they’ve broken up and she walks into his jazz club with her husband, is a memory of a time shared, lost, and treasured, and it’s a beautiful moment of subtlety and grace. (And it helped him get another Academy Award nomination for Best Actor.)

This is the movie that made Gosling a household name, and it’s a romantic drama adapted from a Nicholas Sparks novel. It’s not quite prestigious, of course. But unlike many other Sparks adaptations, in Gosling and Rachel McAdams’s hands, this one glides by. “If you’re a bird, I’m a bird” and “It wasn’t over, it still isn’t over”; the heat and humor with which the pair of them spar and shove ice cream in each other’s faces; that rain kiss, oh my. The Notebook was Gosling introducing himself as not just a hottie, but a considerate, respectful one, a gentleman and a freak, and he’s maintained that duality in his filmography since. He’s played womanizers, but when he falls, he falls hard, and that unwavering adoration is just another facet of Gosling’s ability to play all different kinds of intensity. Plus, Gosling and McAdams gave us the best MTV Movie Awards moment ever by re-creating their iconic cinematic kiss onstage, codifying this movie as a millennial touchstone. For that generation-defining bit of romantic spectacle, we thank them for their service.

Could anyone but Gosling make a near-incel so lovable? As Ken, Barbie’s besotted maybe-boyfriend who can’t ever get a kiss, a sleepover invite, or much attention from Margot Robbie’s titular character, Gosling combines the stewing dissatisfaction of The Believer and The United States of Leland with the elastic-limbed wackiness of The Nice Guys and practically steals the entire movie. Gosling looks like he’s fighting to hold in laughter the whole time, but never does his performance feel farcical or forced. Instead, he captures the contradictory sense of a character who doesn’t understand why he’s feeling what he’s feeling, but sinks into emotion anyway: the drunk-with-infatuation way he gazes at Barbie, the anxious glee in his eyes when he discovers the intoxicating pull of patriarchy, the palpable sadness as he belts out “Is it my destiny to live and die a life of blonde fragility?” during his song-and-dance number “I’m Just Ken.” In a movie that grapples with big questions about purpose, consumerism, and the meaning we give ourselves and what we love, Gosling’s careening performance is a perfect complement to Robbie’s more inquisitive one, and a thoughtful weaponization of all the ways we’ve objectified Gosling’s looks over the years. The man uses his abs as a weapon during a fight in Barbie’s climactic third act, and it’s simultaneously so dumb and so delightful. All hail Ken, our new king of the himbos.

Gosling’s most difficult film, the one with the haziest themes about identity, self-loathing, and religious belief, could have been an unwatchable slog with another actor. But he is blazingly charismatic, and completely horrifying, as a young Jewish man who becomes a neo-Nazi, surrounding himself with fanatics and fascists as he grapples with his own capacity for empathy. Why Gosling’s Daniel hates so fully is never really answered, but the film doesn’t exactly need a cause when the actor’s grasp of its effects are so good. Gosling voices the film’s thought-provoking questions about victimization and villainy with full commitment, and his rigidity — that tall posture, those limitless eyes — add another layer to the work. What could have been just a mimicry of, say, Edward Norton in American History X becomes something distinctly pitiable and unnerving on its own terms, and Gosling chased the heights of this tormented-20-something performance for a long time, up until the next film on our list.

Here’s Gosling’s first Best Actor Academy Award nomination, and it’s deserved. In some ways, 17 years on, Half Nelson shows its age: Gosling stars as Dan, a cocaine-addicted middle-school history teacher in Brooklyn who befriends one of his students, Drey (Shareeka Epps), whose brother is in prison for dealing drugs. With a setup like that, you can probably predict the ways in which Dan and Drey’s relationship will become complicated, maybe even inappropriate, as the school year progresses. Yet Gosling is riveting as a man in free fall, someone whose apologies for his bad behavior are beginning to wear thin on his co-workers, friends, and family. (I’m taking his “It’s just not cool to be a Nazi anymore, baby,” when a date comments on his controversial book collection and asks if he’d read Mein Kampf, as a nicely unintentional nod to The Believer.) The war between regret and self-destruction plays out most unforgettably in a scene where Drey walks into a motel room for a drug deal and finds Dan inside. The little nod he gives her as he holds his money out, the way he’s slumped against the doorframe, how his head rests on his hand like everything about his body is too heavy to move — Dan is broken and beat, but he doesn’t want to scare Drey with it. Underneath all of his fucked-upness, he’s still cogent enough to know that. The best Gosling movies have a moment where he shatters you, and Half Nelson just doesn’t let up.

Here’s Gosling’s hidden talent as an actor: He’s quirkier and more willing to look foolish than many of his peers, and that flexibility gives him a tenderness in situations that might otherwise be too absurd to be taken seriously. Consider Lars and the Real Girl, in which Gosling plays a socially awkward man who struggles to connect with his brother and sister-in-law, co-workers, and fellow townspeople; he’s noncommittal during small talk and he can’t bear to be touched. Gosling makes Lars twitchy and blinky, touchy and sensitive — until he orders a lifelike, RealDoll-style mannequin online that he introduces to everyone in his life as Bianca. As they all indulge him in this fantasy world where Bianca is his girlfriend, Gosling incrementally lets Lars open up, lets him smile, lets him chat, lets him share the personality that Lars had hidden away for so long. Again, like Half Nelson, there’s something a little expected about this plot, and about how Bianca becomes a conduit for Lars’s growth. The balancing act of oddness and affability that Gosling pulls off, though, might make Lars and the Real Girl the most heartwarming film he’s ever made.

Let’s move from heartwarming to heartbreaking: I have only ever watched Derek Cianfrance’s first movie with Gosling once, and I will never watch it again. It’s too annihilating, too much of an evisceration of the idea of true love; this is marriage as the certain creator of despondency and despair, no matter how hard you try. Spanning five years, the film follows Gosling’s Dean and Michelle Williams’s Cindy, who fall quickly and thoroughly in love and then fall prey to the outside forces so many couples do: the difficulty of maintaining work, the difficulty of raising a child, the difficulty of finding time for themselves amid the chaos of day-to-day life. It hurts because it’s so relatable, and because Gosling and Williams are so in tune; the depth they each bring adds legitimacy and poignancy to their ever-increasing fights. Cianfrance prefers close-ups, holding long on Gosling when he’s swearing his love at the beginning of their relationship (all impassioned promises, light flirtation, and eye contact) and tries to understand what he’s doing wrong at the end (his face morphing through befuddlement and indignation); he’s right and he’s wrong at the same time, and that’s Blue Valentine’s clearest calamity. Sometimes things just don’t work out and it never makes sense why, and Gosling embodies that mystery with breathtaking care.

It makes sense that Gosling’s collaborations with Cianfrance should be back-to-back on this list because they are, like so much else of Gosling’s work, a themed pair. Dean in Blue Valentine and Luke in The Place Beyond the Pines are two of a kind, individualistic dreamers who step willingly into responsibility and love fully when allowed to, but can’t quite figure out the right way to provide. A motorcycle stuntman who learns that he has a son with former lover Romina (Eva Mendes), Gosling’s Luke is simultaneously tough and brooding (that bleached hair, all those tattoos, his ease on a bike) and nakedly craving something more. Gosling’s most emblematic line as Luke — “I’m still his father, I can give him stuff” — is all that ache bundled into an admission he looks almost surprised to make, and those little glimpses of wonder, when Luke looks thrown by his own confessions of loneliness, permeate this performance. Gosling’s only in the movie for a third of it, but he looms phenomenally large; it’s a sign of his potency as an actor that the entire rest of The Place Beyond the Pines arcs around the bone-deep impact of his character’s tragic end.

There are people who will tell you that Blade Runner 2049 should never have been made because the first film was so strong in its ambiguous ending, that it’s misogynistic, that replacing Sean Young with a CGI re-creation was disrespectful, that it’s all style over substance. We had this very discussion here at Vulture, and some points were made! But at the very least, in the unenviable ask of replacing Harrison Ford, Gosling is an equipped answer. His performance as replicant Officer K never feels like a re-creation of Ford’s as blade-runner-and-maybe-replicant Deckard in 1982’s Blade Runner, but an evolution of it, one that’s infused with the qualities Gosling does so well: a sense of something simmering underneath the surface, a fist-clenched level of control, and a longing to be perceived. The film hands Gosling an array of revelations and experiments, including the turmoil of his failed baseline test (“Do you feel that there’s a part of you that’s missing?”) and the delicacy of his half-virtual sex scene with Mackenzie Davis and Ana de Armas, and the little cracks of interiority he brings to them reflect the film’s musings about what makes us human, or more human than human. It’s a performance of increments, and it’s the second-finest display of how Gosling can uniquely swing between placidity and fury.

The best expression of that extreme oscillation is in Drive, his first collaboration with Refn that birthed cool-guy Gosling. The trick of this film is how it mutates the ferment and turbulence of Gosling’s previous work in films like The United States of Leland, Stay, and Murder by Numbers. His car, his hammer, his scorpion bomber jacket: All are accessories to the yawning hollowness Gosling’s Driver has clearly spent years protecting inside himself. When the characters played by Carey Mulligan and Kaden Leos begin to tiptoe into that void, Gosling sells the Driver’s transition into a man finally come alive, revitalized by love and purified by violence. A real human being and a real hero, indeed. (And it’s still the coolest he’s looked onscreen. Those leather driving gloves, yowza.)

The erasure of the R-rated comedy has been a distinct loss for movies, and The Nice Guys remains one of the best recent examples of what we’re missing out on. Gosling and Russell Crowe are perfectly at home in Shane Black’s ’70s-set neo-noir as a PI and enforcer who start trying to find a missing adult-film actress and get sucked into a larger conspiracy related to the auto industry and the environmental-protection movement; the actors chomp through Black and co-writer Anthony Bagarozzi’s pithy and dense dialogue like they can’t get enough of it. They’re agreeably matched foils, with Gosling settling into a high-pitched dandy mode that is gleefully oppositional to Crowe’s grizzled aura. Who knew Gosling was such an entertaining screamer and such a devoted physical comedian? This role is so different from all his other work that it ricochets up in esteem, proving how far Gosling can push himself when given the chance. The Nice Guys moves to the rhythm of one ludicrous Gosling moment after another — the peevishness with which he defends jumping into a pool of half-naked women because “I had to question the mermaids”; the flailing about in a bathroom stall as he smokes and brandishes a gun on the toilet — and it’s a failure of our industry that it took seven years to get this man back in the comedic vein with Barbie.

First Man, the Neil Armstrong biopic that is Chazelle’s second collaboration with Gosling, feels like watching Gosling act his way out of a straitjacket. The character is so constrained that every scene is charged with the energy Gosling is using to stay wound, to stay tight; it’s only through the most minuscule adjustments that we understand the cataclysmic forces fighting inside Gosling’s mind. Armstrong’s courting death every day at NASA in the name of discovery and avoiding death every day in a home consumed by grief for his passed-away daughter. It’s enough to tear a man apart, and Gosling conveys that encroaching disintegration with every silent gaze and every set of his jaw. The performance is so powerful not just because of Gosling’s self-composure, but because of how he points that severity at others — the appealing looks he gives wife Janet, played by Claire Foy, who wants more communication from the man she loves; his evident agony, but increased resolution, when he learns of yet another colleague and friend’s death as the pilots train to make it to the moon.

What can an actor convey with their body alone? Not their voice and not their face, but just their stance and the character they’ve built up until that point? First Man’s moon-set climax, when the spacesuit-clad Gosling drops Armstrong’s daughter’s bracelet into the Little West crater as a way to let go of his grief, is so cathartic because we know the weight of that choice and the tiny glimmer of resolution it provides, thanks to Gosling’s preceding thoroughness. Justin Hurwitz’s theremin-and-synth score is integral, but the scene — and the movie overall — wouldn’t be a fraction of what it is without Gosling’s extraordinary emotiveness. It’s first-rate.

:quality(85):extract_cover()/2023/04/11/665/n/1922398/1bca5fbd643575b356f110.11047203_.jpg)