A late summer time prairie wind swung my beaded earrings as I looked down at a gray-and-black sample on a computer system screen. The grass beneath my toes quieted as I paused. A disruption appeared, changing the radar image on the display screen. My breath caught. “There,” I considered, anticipating what may possibly appear to light when we took the knowledge back again to the lab. My feet grew heavier, as did the ache in my heart.

I will in no way get employed to strolling over the land that may hold the unmarked graves of Indigenous small children.

I did not start off my journey as an Indigenous archaeologist in Canada with the intention of working with the dead. But I now discover myself making use of my technical information and study qualities to enable my relatives discover the unmarked graves of our kids. Starting in the late 1800s and more than the program of much more than century, Canadian authorities forcibly eliminated additional than 150,000 Indigenous young children from their families and positioned them in household faculties. Thousands in no way arrived property. In modern many years, many Very first Nations have started the sacred and challenging perform of trying to uncover the kids who are shed, and they are contacting on archaeologists for assist.

On supporting science journalism

If you might be making the most of this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By buying a subscription you are aiding to make certain the future of impactful tales about the discoveries and tips shaping our world currently.

Together the way, folks have received a much better comprehending of how difficult it can be to come across the answers that people of missing small children have earned. But even when radar surveys locate anomalies in the soil that may point out an unmarked grave, a great deal of uncertainty remains. Present-day archaeologists are collaborating with survivors and communities to provide with each other all the information and facts they can to locate the youngsters and carry them dwelling.

These endeavours are an illustration of how archaeology is transforming to come to be a lot more engaged, additional ethical and additional caring about the people today whose previous we are privileged to study. Historically, archaeologists have gathered Indigenous belongings (contacting them “artifacts”) and ancestors (“human remains”) with out the consent of descendant peoples and made use of these to formulate theories about their previous lives. In distinction to this major-down solution, archaeology is now being applied to guidance restorative justice for communities who have been traditionally and systemically oppressed.

This new archaeological apply, which I describe as “heart-centered,” provides my colleagues and me back in time to the destinations touched by our ancestors. We use the product items they left behind to attempt to reanimate their life, revive their stories—and, by informing their descendants of what grew to become of their cherished kinds, to help bring closure and heal trauma. Nevertheless the journey is prolonged, archaeological techniques can be utilized to convey to the tales of the previous, both of historical Indigenous life and the impacts of colonization, to enable construct a brighter potential.

In 2021 the unmarked graves of about 200 Indigenous children had been observed near the previous Kamloops Indian Residential School.

Alper Dervis/Anadolu Agency by means of Getty Pictures

The nation known as Canada and the colonies that preceded it developed insurance policies and procedures made to remove the strategies of lifestyle of Indigenous peoples. Central to this energy were govt-funded, church-run household educational facilities. Established in the 1880s, these institutions incarceratedIndigenous children—separating them from their family members and forcing them to go to, indoctrinating them into Christianity and punishing them for speaking their have languages or participating in their personal cultural practices. “I want to get rid of the Indian difficulty,” mentioned Duncan Campbell Scott of the Department of Indian Affairs in 1920 upon mandating university attendance for Indigenous small children. “Our goal is to continue on until there is not a solitary Indian in Canada that has not been absorbed into the human body politic and there is no Indian problem.”

The household college method tore households aside and put little ones in environments of bodily, psychological, cultural and normally sexual abuse. Thousands of them died at educational facilities from neglect, substandard dwelling situations, illnesses, malnutrition and abuse. Some had been buried in cemeteries or graveyards at the colleges, even though many others ended up disposed of in additional clandestine means. Dad and mom were being often not notified of their children’s dying their little ones only in no way came house.

Survivors of the universities shared their information about their lacking companions for decades, but neither the churches nor the federal federal government took sizeable motion to come across the remains. Also usually, these testimonies ended up overlooked or downplayed. In excess of time, physical markers that could have indicated the places of the graves ended up erased via the two neglect and deliberate actions. In the 1960s, for case in point, a Catholic priest eliminated the headstones from the cemetery of the Marieval Household College at Cowessess, Saskatchewan. Other cemeteries ended up decommissioned and erased from the landscape. It took Canada’s Fact and Reconciliation Fee, which revealed its to start with shattering stories in 2015, along with the announcement of the outcomes of ground-penetrating radar surveys performed by Very first Nations investigators in 2021, to deliver the horror of household educational institutions into the worldwide spotlight. The trauma inflicted by household universities have impacted Indigenous individuals across generations. My good-grandmother attended a residential school, and this sacred get the job done is therefore element of my own journey of healing and coming household.

In 1953 my then 19-yr-aged grandmother gave start to my father in a Catholic healthcare facility in Edmonton, Alberta. She was component of the Métis Country, an Indigenous identification that emerged out of early unions in between European fur traders and Indigenous gals. The descendants of these unions formed a group with a unique way of lifetime, society, and language and are now one of 3 recognized Indigenous groups in Canada.

Young, unmarried and Indigenous, my grandmother was not given a probability to increase her firstborn son. Following she remaining the hospital, she hardly ever observed him once again. The little one was taken from her and deposited in an orphanage, where by he invested the first two decades of his existence. A lot of of these orphanages operated like residential universities in reality, some household schools housed orphanages, these as the St. Albert Indian Residential School, also referred to as Youville, in Alberta. Then came foster care—my father bounced from family members to family members right before he at last landed in a extra stable placement with a French-Canadian farming family. In no way adopted, he expended two unfulfilling and alienating decades as an undergraduate at the College of Alberta before leaving driving his Métis homeland.

In his early 20s, he met my mother, a lady of European (mostly British) descent, in British Columbia. I was born and raised absent from my ancestral homeland of prairie fields and thunderstorms. My childhood was in its place expended exploring the towering cedar trees and moist mosses of the temperate rain forest close to the Pacific coast. I experienced an uncommon upbringing, remaining homeschooled for considerably of my childhood. My pursuits were being extensive-ranging, but in my teenage many years, my father released me to archaeology, and it sounded like the most fascinating and adventurous lifetime, touring all around and checking out ancient destinations. My route forward seemed obvious.

Archaeology emerged as a self-discipline in Europe and was introduced to North The usa as section of colonial institutions these as universities and museums. Early archaeologists, virtually all of them nonindigenous, excavated Indigenous sites and took what they uncovered to museums. They framed themselves as the rightful stewards of Indigenous pasts, making use of our creations and ancestors for their scientific experiments without our involvement or consent.

In the 1970s and 1980s, coinciding with codification of human and civil rights legislation, archaeologists began to connect with for a shift towards knowledge personal activities of assorted peoples from the previous. Concurrently, quite a few Indigenous activists ended up pushing for museums and universities to return ancestors to their communities, foremost to the passing of the Native American Graves Defense and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) in the U.S. in 1990. This act needed institutions that acquired federal funding to stock and return ancestors and burial objects where ever cultural affiliation could be demonstrated. It induced consternation amongst numerous archaeologists and organic anthropologists, who voiced concern that their respective fields ended up in hazard. They had been so utilised to the strategy that nonindigenous students experienced a ideal to research no matter what they desired about the past, even if living Indigenous men and women strongly disagreed, that returning the stolen ancestors appeared a sizeable danger to the foundations of their willpower.

As a teenage archaeology fanatic in the mid-1990s, I experienced no concept about the improvements transpiring in the area, and yet they had a big effects on my education. I was educated immediately after NAGPRA and in British Columbia, where quite a few archaeologists ended up doing the job intently with Indigenous communities.

In 2001 I excitedly stepped off a boat—I keep in mind the midsummer sunshine glinting off its steel hull—onto a rocky shore. I was an undergraduate at the College of British Columbia, and my classmates and I were on the territory of the Sq’ewá:lxw Initially Nation, along the decrease Fraser River in British Columbia, to master discipline archaeology. I glimpsed the wealthy red ocher unfold throughout the insides of my wrists in advance of instinctively brushing my fingers against my temples to verify that I remembered to set the paste there. The ocher allowed us to be obvious to the ancestors whilst digging at the archaeological website close by every person stepping off the boat that working day had to comply with this protocol.

Strolling up the mild slope to the excavation that awaited, I fell into dialogue with our community partners from the Sq’ewá:lxw Nation. As they shared their knowledge and connections with the past, they were being as a great deal our teachers as the teachers on web site were. They aided me, an Indigenous scholar moving into my very last calendar year of university, keep on my own journey of reconnecting with my ancestors. The Sq’ewá:lxw elders planted seeds in my thoughts that led me to where I am today: using archaeology to aid Indigenous communities discover our small children.

Survivor Evelyn Camille was compelled to expend a 10 years at Kamloops Indian Residential College, in which, she claimed, the pupils have been subjected to actual physical and sexual abuse.

Cole Burston/AFP via Getty Pictures

In mid-2021 Tk̓emlúpste Secwépemc Nation announced that about 200 possible graves had been detected in the vicinity of the grounds of the former Kamloops Indian Residential Faculty in British Columbia. Although perform to identify unmarked graves had been ongoing at other spots, this announcement introduced unparalleled attention to the difficulty of unmarked graves. The community had worked with an anthropologist who used ground-penetrating radar to identify these potential grave internet sites.

Since that announcement, lots of archaeologists have been called on by Indigenous communities in Canada and the U.S. to support find the unmarked graves of their youngsters. This collaboration signifies a considerable alter: communities that have been the unwilling topics of archaeological investigation in the previous are now asking for assistance.

Supporting Indigenous communities in this distressing undertaking needs archaeologists to guide from the coronary heart. It is psychological and really sensitive perform, necessitating good treatment, sincerity and scientific rigor. Rather of an extractive exercise that takes awareness, possessions and ancestors absent from Indigenous communities, this new archaeology can support redress and restorative justice.

In 2020 3 colleagues and I released a e book envisioning a heart-centered archaeological exercise flowing as a result of the 4 chambers of treatment, emotion, relation and rigor. We invited fellow archaeologists to care for the living and the lifeless, to recognize the psychological content material of archaeology (these kinds of as the feelings inherent in the lives of historical peoples and evoked by the materials they applied), to take that the previous relates to the present (so it is important to build ties with the dwelling and respect their boundaries) and lastly to admit that rigor comes in lots of forms (all know-how units have inner rigor that establishes what the mother nature of awareness is, who has knowledge and how awareness is handed on).

It is also in heart-centered archaeology that I can find a place to be the two an archaeologist and an Indigenous individual. It has taken me a life span, but I am finally below, practising archaeology in my have way that respects my Métis relations. My heart has brought me back again dwelling to my homelands. The marriage I have created with my neighborhood has introduced me to the most significant and sacred function I could imagine: serving to to discover the lacking young children. I am studying the stories of my spouse and children, including my wonderful-grandmother, the a single who attended a residential college, and my grandmother’s initially cousin, who died at the age of seven and was buried in a cemetery beside a residential university. I am studying the truths of our practical experience, doing the job to heal so my young daughter can have a brighter upcoming.

Two a long time immediately after my undergraduate function in 2001, I sat down with a survivor of a residential schoolin a setting up that was appropriate upcoming door to what was as soon as these kinds of a college. A church spire from the mission that experienced run the establishment was visible through the window. A crispness in the slide air carried the guarantee of a frigid prairie wintertime to occur. I lit the sage leaves gathered in a tiny forged-iron pan, the flame from the wooden match generating a burst of heat. Tendrils of aromatic smoke enveloped me as I pulled the cleaning smudge, or smoke, toward my eyes, my ears, my mouth, my coronary heart. I stood, my ribbon skirt constricting my motion, to present the survivor the smudge, knowing the pain that would arrive with what the workforce was about to share.

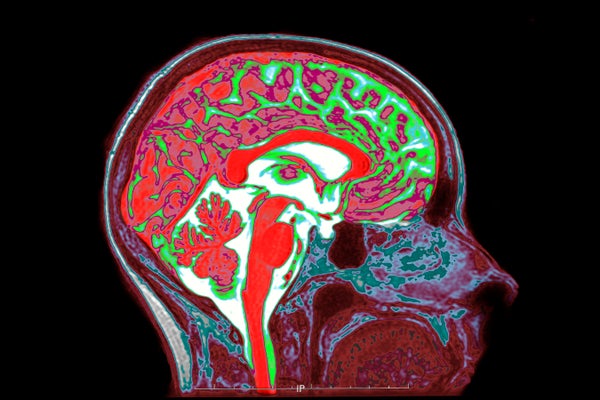

Earlier that working day, I experienced surveyed the area guiding the faculty with floor-penetrating radar when my staff analyzed the visuals that appeared on my computer system display screen. Back in the lab, the details experienced settled into a number of colorful oval shapes on a white track record, every single about 3 ft long, a few feet deep and equally oriented. These were being most probably buried small children. No trace of their graves remained obvious on the grassy area guiding the household faculty making, whose shadowed home windows hid lots of secrets nevertheless to be identified.

I told the survivor what the group had uncovered. They necessary to stage away the grief and agony had been overpowering. I stepped absent, as well, simply because I heard my possess coronary heart echo their heartbreak. Each individual of these designs represented a cherished little one. Nevertheless the search was only commencing. Countless numbers of graves experienced nonetheless to be found—and we have been coming to phrases with the reality that we would in no way discover them all.

How lots of instances can you split a damaged coronary heart?

There is nevertheless a long journey in advance. Many web sites bordering the residential colleges have not even begun to be searched. The landscapes of these institutions are broad, and the method of searching is gradual. It will choose many years of do the job to track down possible graves, and Indigenous individuals proceed to examine the query of what takes place as soon as they are positioned. But possibly, just after yrs and years of inquiring, there might be some accountability for all those responsible for getting the little ones away—only if the governing administration and churches help the operate to come and the general public keeps the strain on for serious action.

The journey for archaeology as a self-control is equally hard. There are nevertheless individuals in our discipline who insist that collaboration with Indigenous communities and the return of ancestors are a danger to the pretty foundations of our willpower. But if a basis is essentially flawed, do we just carry on creating the exact same way, or do we visualize a different foundation?

We can, and will, do greater. And we will support locate the kids.

:quality(85):upscale()/2024/05/20/902/n/43463692/10615bcd664bb4fc410645.14729823_.jpg)