A costume, an accent, a narrative manner, a homecoming: For Beyoncé, state tunes is all that (and more) on “Cowboy Carter,” the pop superstar’s boot-scooting blowout of a new studio album. It’s as sprawling and as arduous as we have come to anticipate from the most intellectually bold artist in new music it also can make you marvel — and this of system is easy for me to say — no matter whether Beyoncé should really stop trying to find the approval of individuals who’ve revealed by themselves unworthy of bestowing it.

Identified as normally to introduce her work on her have conditions, Beyoncé wrote on Instagram right before the LP’s release on Friday that “Cowboy Carter” was “born out of an experience that I had years in the past where I did not come to feel welcomed” — a reference, presumably, to the racist backlash that greeted her effectiveness of her song “Daddy Lessons” with the Dixie Chicks at the 2016 Country Audio Assn. Awards. The episode led her to immerse herself in the “rich musical archive” of country music’s undersung Black pioneers, just as she’d examined the Black and queer roots of dance tunes to make 2022’s “Renaissance.” (“Renaissance” and “Cowboy Carter” are billed as the initially and 2nd acts in a proposed trilogy, though Beyoncé’s reign as pop’s foremost musicologist really began with the tribute to HBCU custom she brought to Coachella in 2018.)

As a very pleased Houston native — “the grandbaby of a moonshine man,” as she places it in the new album’s opener, “Ameriican Requiem” — Beyoncé’s connection to place music operates deep: “Got people down Galveston, rooted in Louisiana,” she sings in “Ameriican Requiem,” a surging march layered with guitar, sitar and the hum of an electrical church organ. “Used to say I spoke too state / Then the rejection came, mentioned I was not country ’nough.” The similar went for “Renaissance,” whose excursions into household, disco and ballroom songs she linked to her shut partnership with a homosexual household member named Uncle Johnny.

And, certainly, it is the particulars of Beyoncé’s identification that give her tunes a lot of its cultural excess weight — that posture her here as a Black woman endeavoring to make space for men and women of colour in a discipline that’s prolonged proved inhospitable to any individual other than straight white men. By now she’s been criticized by some on social media for doing significantly less than she could in that regard on a record that prominently attributes Miley Cyrus and Publish Malone though it convenes 4 Black female place singers — Tanner Adell, Brittney Spencer, Tiera Kennedy and Reyna Roberts — to provide as her backing refrain in a relocating include of the Beatles’ “Blackbird.” Other visitors incorporate Shaboozey and Willie Jones, each country-rap fusionists, and the state elders Willie Nelson, Dolly Parton and Linda Martell, all of whom present spoken interludes.

Still it’s the pop star’s prerogative to borrow freely from regardless of what and where ever she likes the determinist wondering close to Beyoncé can downplay pop’s legitimate assure, which is that one’s expertise and ingenuity are all the license a person demands. Undoubtedly, that flexibility is relished additional readily by the likes of Malone (whose presence on November’s CMA Awards appeared to rankle no one) and Morgan Wallen (who’s carried out as significantly as any country act to import features of Black creative imagination into a putatively white genre — always a a lot more frictionless approach than the reverse). But the most thrilling moments on “Cowboy Carter” are not feats of reclamation so a lot as achievements of invention: tricky-to-classify songs this kind of as “Sweet Honey Buckiin’,” in which Beyoncé croons Patsy Cline’s “I Slide to Pieces” over a thumping Jersey club groove, or “II Hands II Heaven,” a celestial trance-folks fantasia that evokes a extensive evening in the desert.

As a grand statement on The us — the sort the album’s protect sets you up for with its hanging stars-and-bars symbology — “Cowboy Carter” feels a little bit mushy. Beyoncé sings in “Ameriican Requiem” about “a quite dwelling that we hardly ever settled in” and notes in “Ya Ya” that there is “a entire lot of crimson in that white and blue” the latter tune, which estimates Nancy Sinatra and the Beach Boys and summons reminiscences of Tina Turner, also lamely addresses the anxieties of persons exhausted from “working time and a half for 50 % the pay”: “We gotta hold the religion,” Beyoncé advises. Oh, is that all?

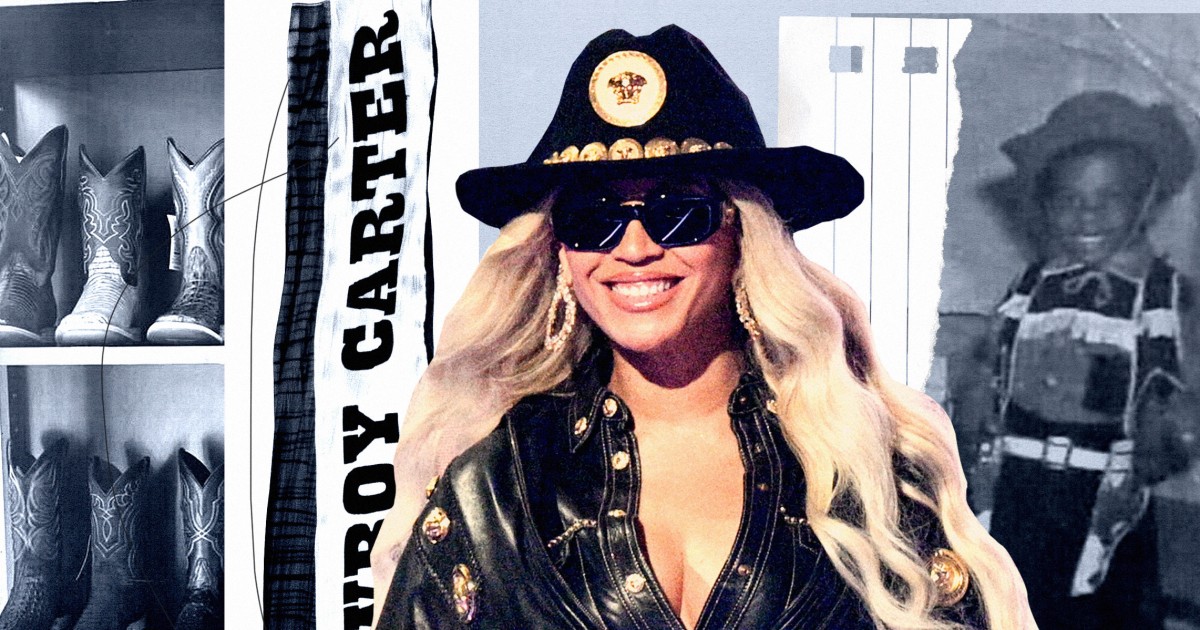

The deal with of “Cowboy Carter.”

(Parkwood Enjoyment / Columbia Data)

She’s mentioned that just about every music was conceived in response to a precise Western film (among the them “Urban Cowboy” and “The Hateful Eight”), which signifies they could be a lot less strictly autobiographical than Beyoncé has trained us with LPs like “Lemonade” to presume. The breezy “II Most Needed,” for instance — with Beyoncé and Cyrus harmonizing about smoking cigarettes cigarettes though “flying down the 405” — may perhaps nicely be a riff on “Thelma & Louise.” (Two extremely own exceptions are the stately “16 Carriages,” about the youth she invested constructing a occupation on the highway, and “Protector,” a tender acoustic ballad in which she describes the bond among mom and child — and which begins with Beyoncé’s daughter Rumi inquiring her mother for a lullaby.)

However that a bit gimmicky storytelling approach appears to have unlocked her creativity it’s gratifying to hear her lean not just into nation music’s background but into its wit and model and pageantry. “Levii’s Jeans” — all these double i’s are evidently meant to boost “Cowboy Carter’s” Act II status — is a sexed-up duet with her and Malone trading cheeky strains about the charms of hip-hugging denim “Riiverdance” blends programmed beats and a speedy finger-picked guitar lick like almost nothing considering the fact that Rednex scored a remaining-field strike with “Cotton Eye Joe” in 1995. Her singing is just as vivid and assorted throughout the LP, with gutsy growls and breathy trills in opposition to multi-tracked harmony vocals that approximate the heavenly abundance of a gospel choir.

Like “Renaissance,” “Cowboy Carter” reflects the fantastic treatment Beyoncé usually takes in structuring her albums: Witness the way she moves from “Bodyguard,” a ’70s-design and style delicate-rock jam, to an interlude by Parton, whose “I Will Usually Enjoy You” was covered by Whitney Houston in “The Bodyguard,” to a rendition of Parton’s “Jolene,” in which Beyoncé remakes the initial lyric as a bare-knuckle risk, to “Daughter,” a stark murder ballad that explores a family’s legacy of violence.

That perception in the prospective of the album structure is just one cause that Beyoncé’s tortured past at the Grammy Awards, in which she’s misplaced album of the calendar year 4 periods, remains these a vexing element of her tale up there with the CMAs incident that set “Cowboy Carter” into movement. Nonetheless, it is really hard not to cringe when she evidently refers to her most new defeat in album of the yr — AOTY for shorter — with the eminently deserving “Renaissance.” “A-O-T-Y, I ain’t get / I ain’t stuntin’ ’bout them,” she raps in “Sweet Honey Buckiin’,” “Take that s— on the chin / Come back and f— up the pen.”

Beyoncé employed that enthusiasm to supply the intriguing “Cowboy Carter.” But no gatekeeper can consider credit for her vision.

:quality(85):upscale()/2024/03/08/999/n/1922729/c57e1d7c65eb981d692c87.22101633_.jpg)